Lecture 5: Thermal Energy of Gases (part 2) and the Zeroth Law

0) Orientation, live demo, and quick recap

A live demonstration of the elastocaloric effect, using an elastic band, illustrates fundamental thermodynamic principles. When rapidly stretched, the band warms; holding it stretched allows it to cool to ambient temperature; and a sudden release causes it to cool. Students observe these subtle temperature changes by touching the band to their lips, which are sensitive to small thermal differences. This demonstration intuitively introduces the relationships between work, heat, and internal energy, with a full microscopic explanation reserved for later lectures. Today's session completes the microscopic derivation linking gas particle motion to temperature, introduces the Zeroth Law and precise thermodynamic terminology, places temperature on an absolute (Kelvin) scale, explains its measurement, and offers a glimpse into the microscopic meaning of temperature via the Boltzmann factor. The underlying model for these derivations is the ideal gas, which assumes many identical, non-interacting, point-like particles undergoing elastic collisions and random motion. The very word "gas" derives from "chaos," reflecting this inherent randomness.

# 1) From wall impacts to pressure: finishing the kinetic-theory link

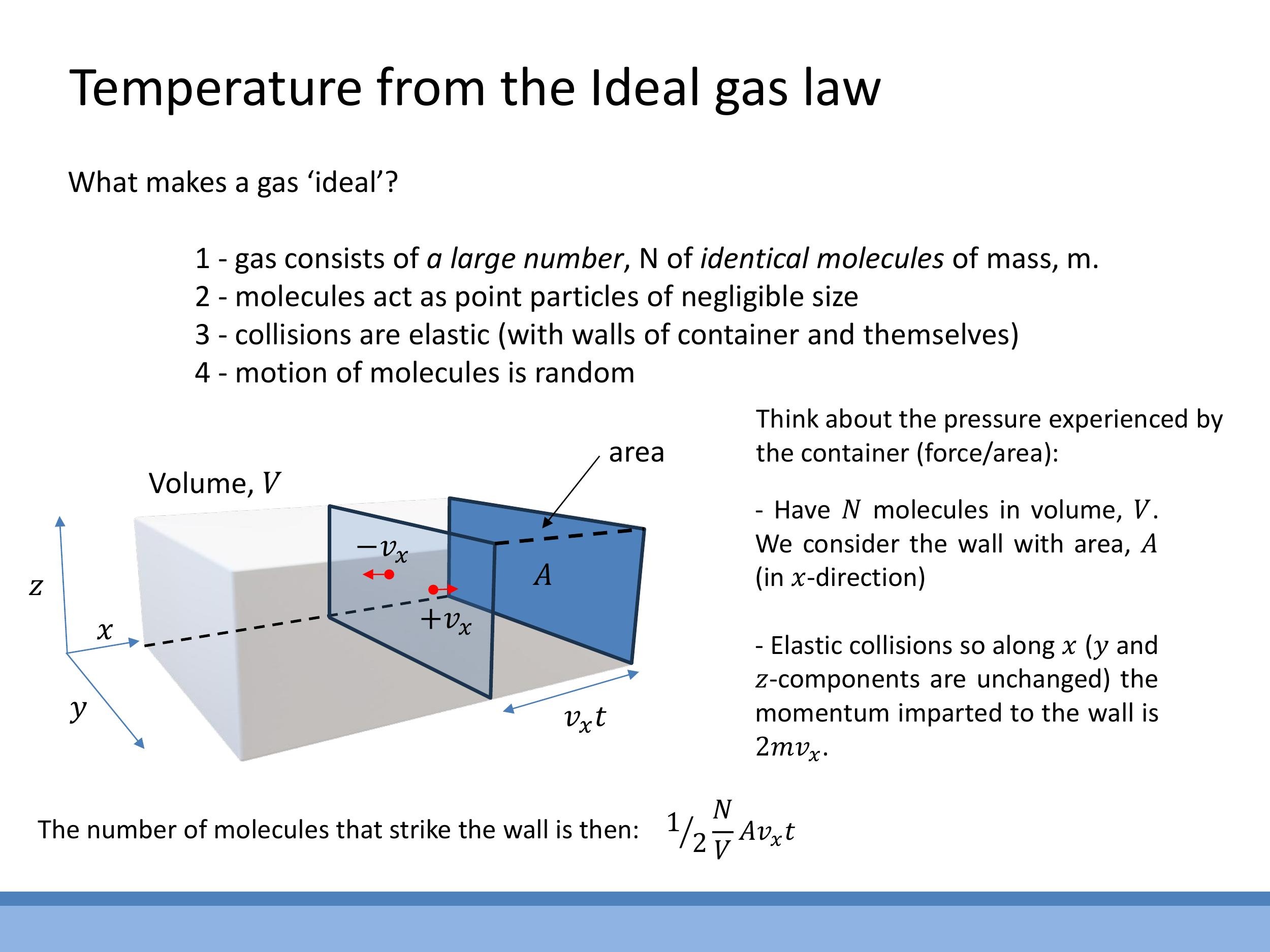

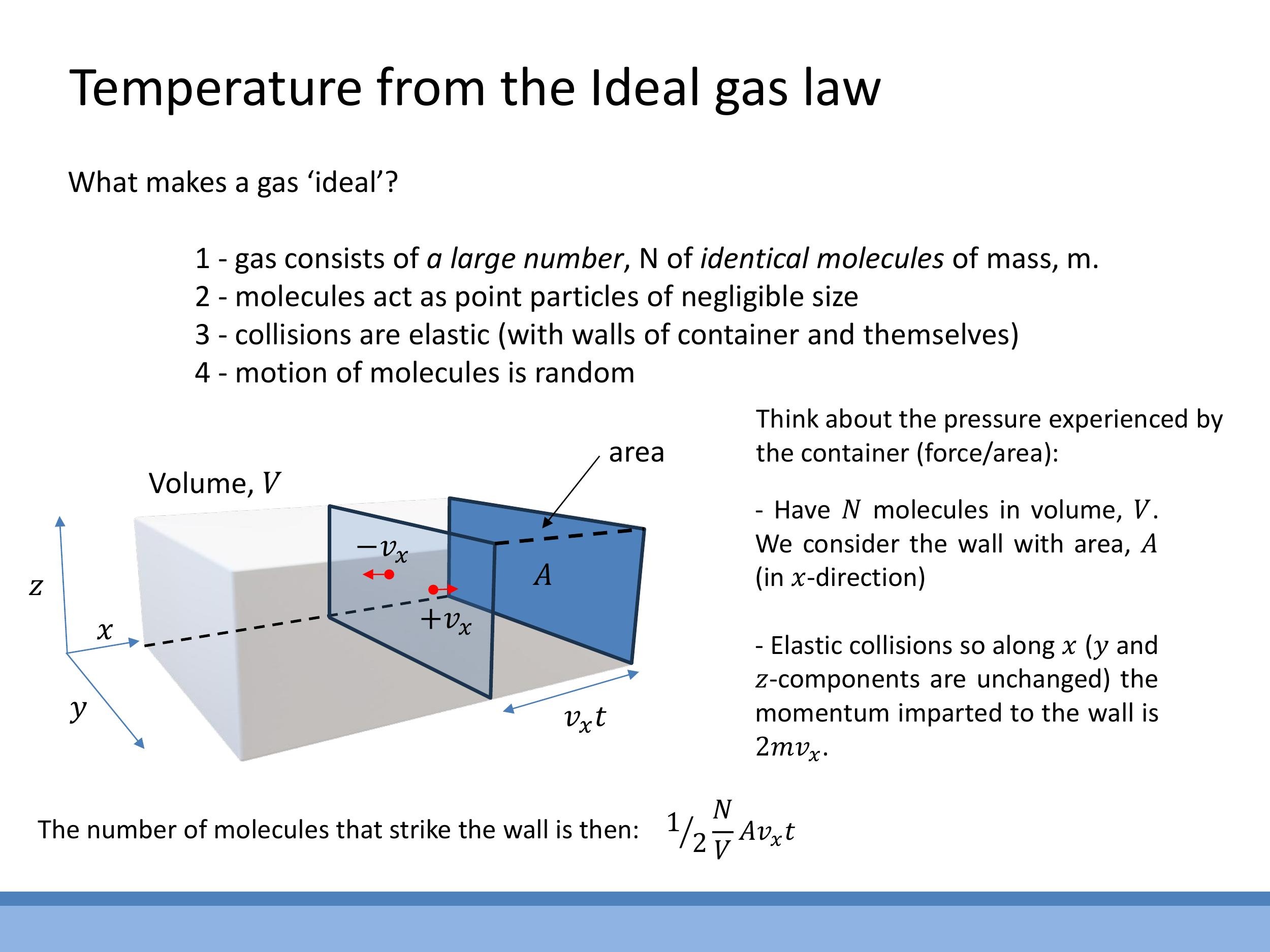

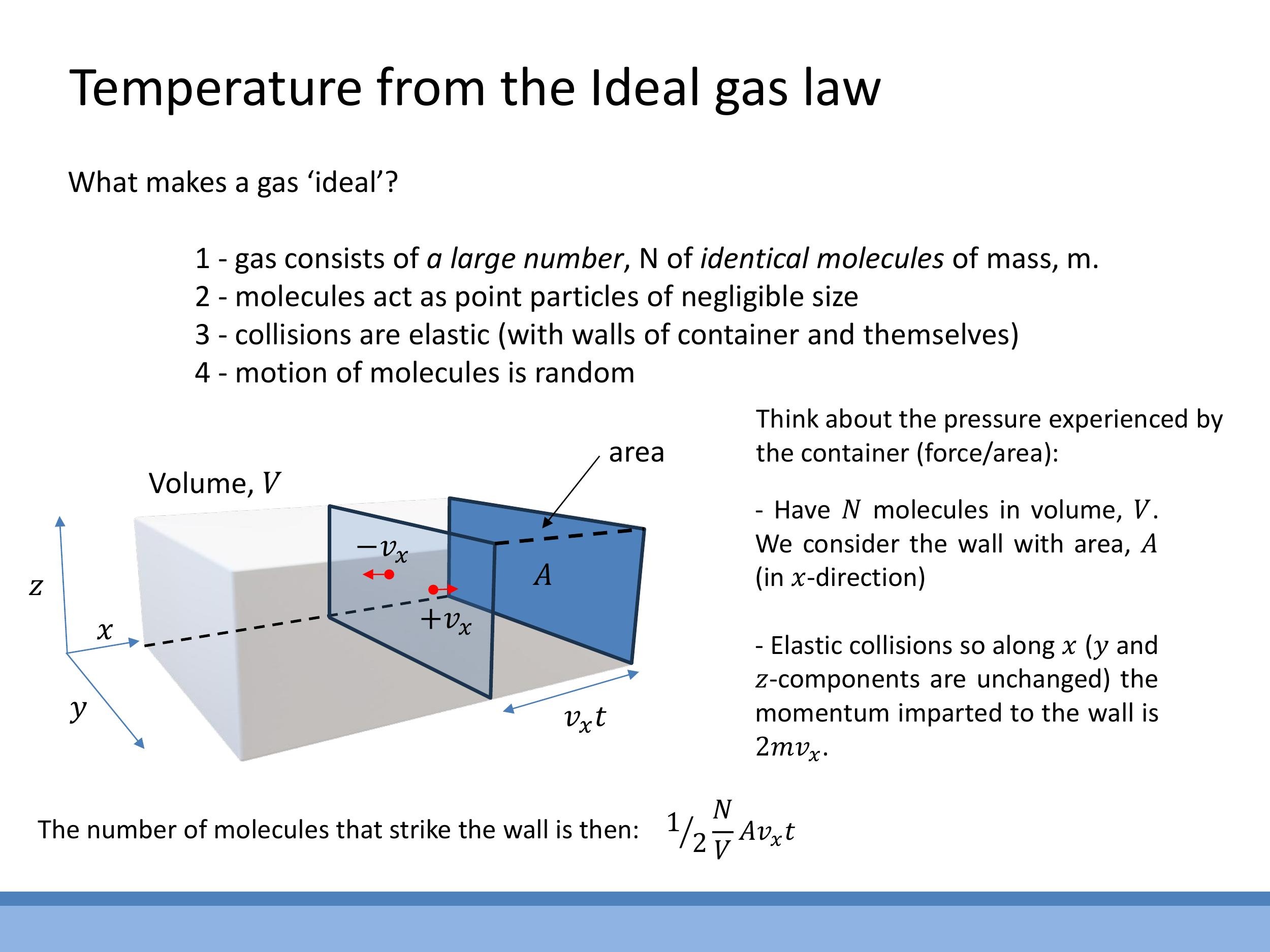

Pressure, defined as force per unit area, results from the transfer of momentum when gas molecules elastically collide with the container walls.

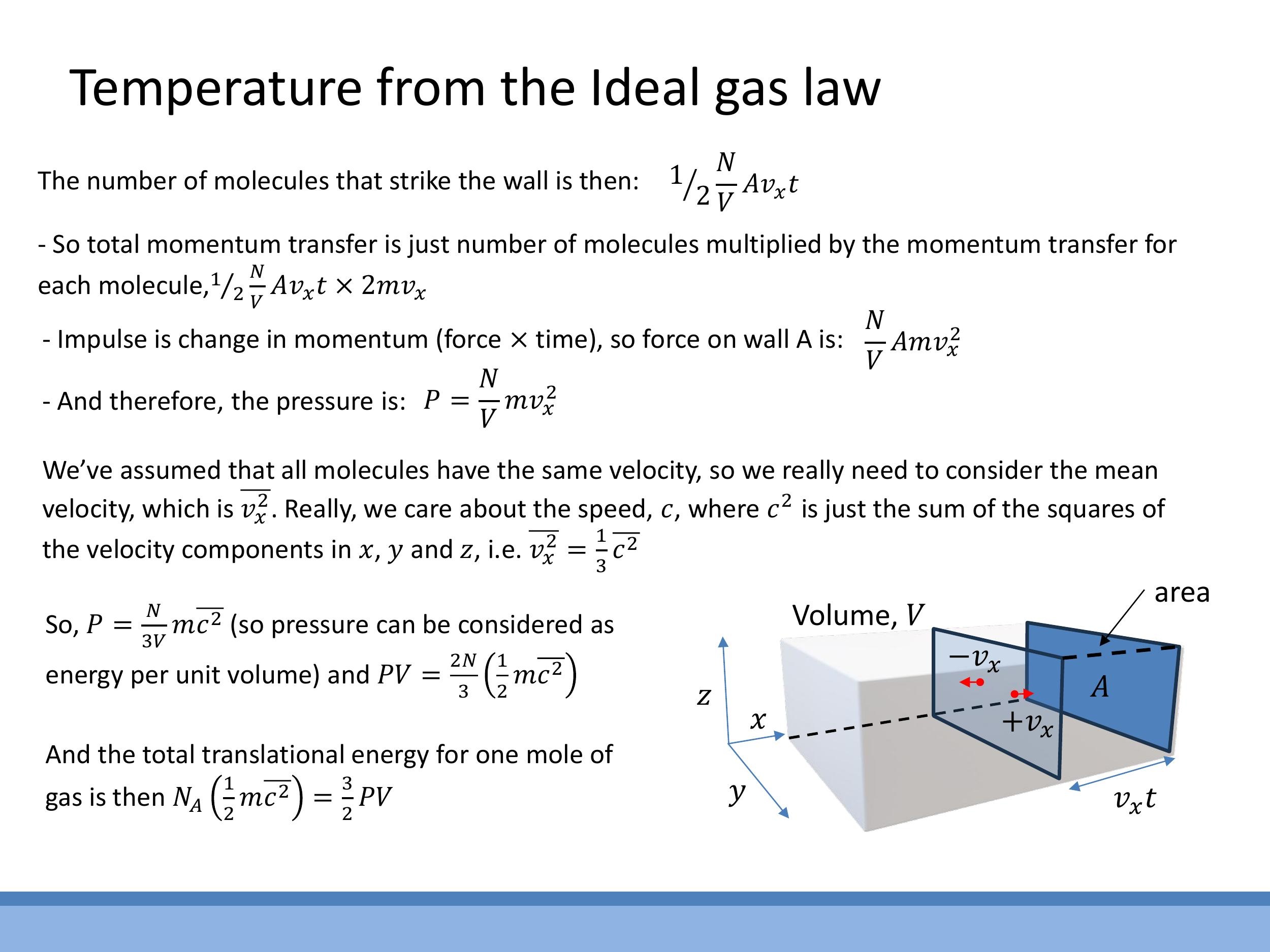

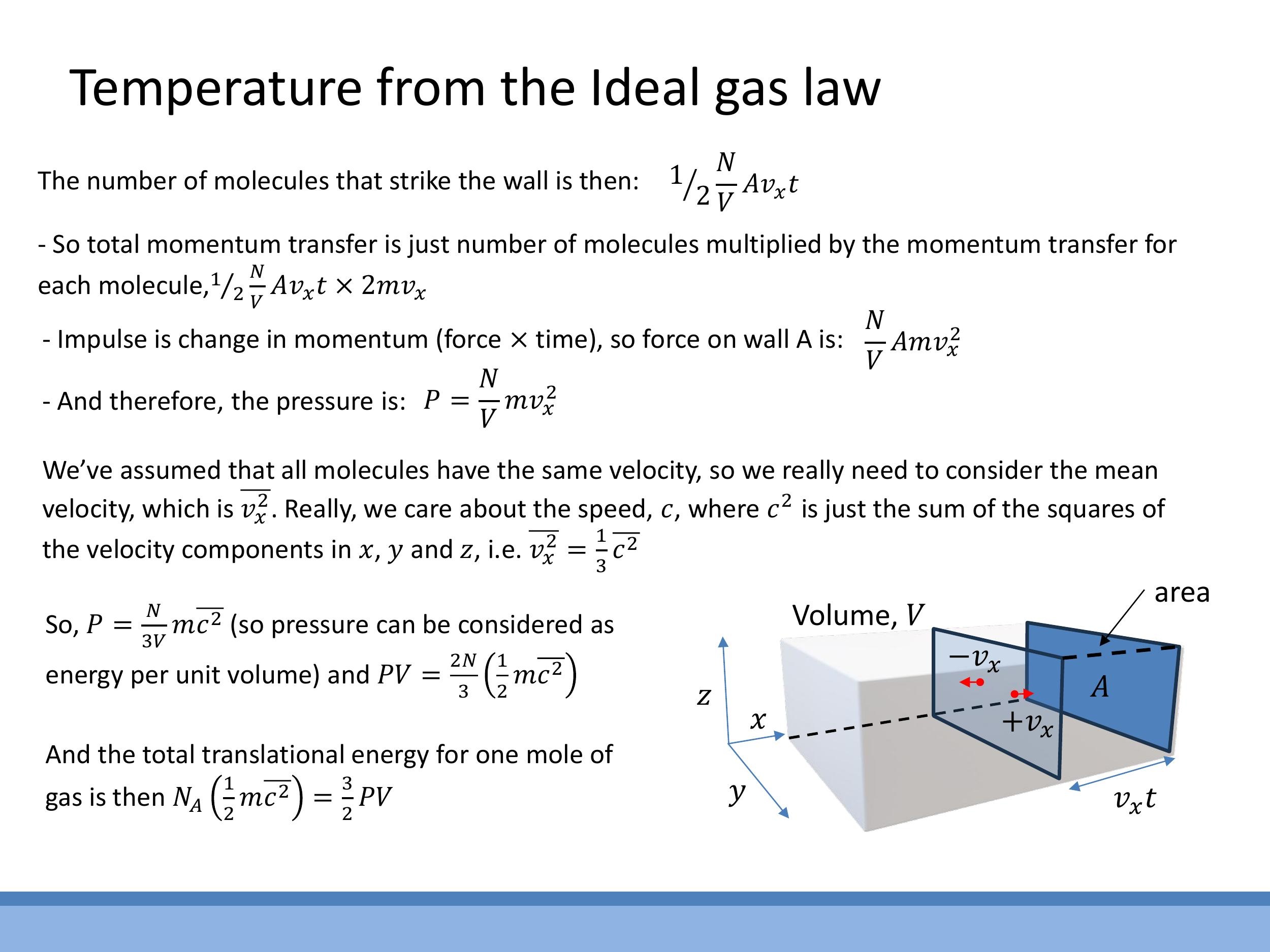

For a single molecule of mass $m$ with an $x$ -component of velocity $v_x$ that collides elastically with a wall, the change in momentum imparted to the wall is $2mv_x$. The number of such collisions on an area $A$ in time $t$ by molecules moving towards the wall is given by $\frac{1}{2}\frac{N}{V} A v_x t$, where $N$ is the total number of molecules and $V$ is the volume. The factor of $\frac{1}{2}$ accounts for, on average, half of the molecules moving in the direction of the wall. The total impulse, which is force multiplied by time, is the product of the number of hits and the momentum change per hit: $\left(\frac{1}{2}\frac{N}{V} A v_x t\right) \times \left(2mv_x\right)$. Dividing this total impulse by time $t$ yields the force on the wall, and further dividing by the area $A$ gives the pressure: $P = \frac{N}{V} m v_x^2$.

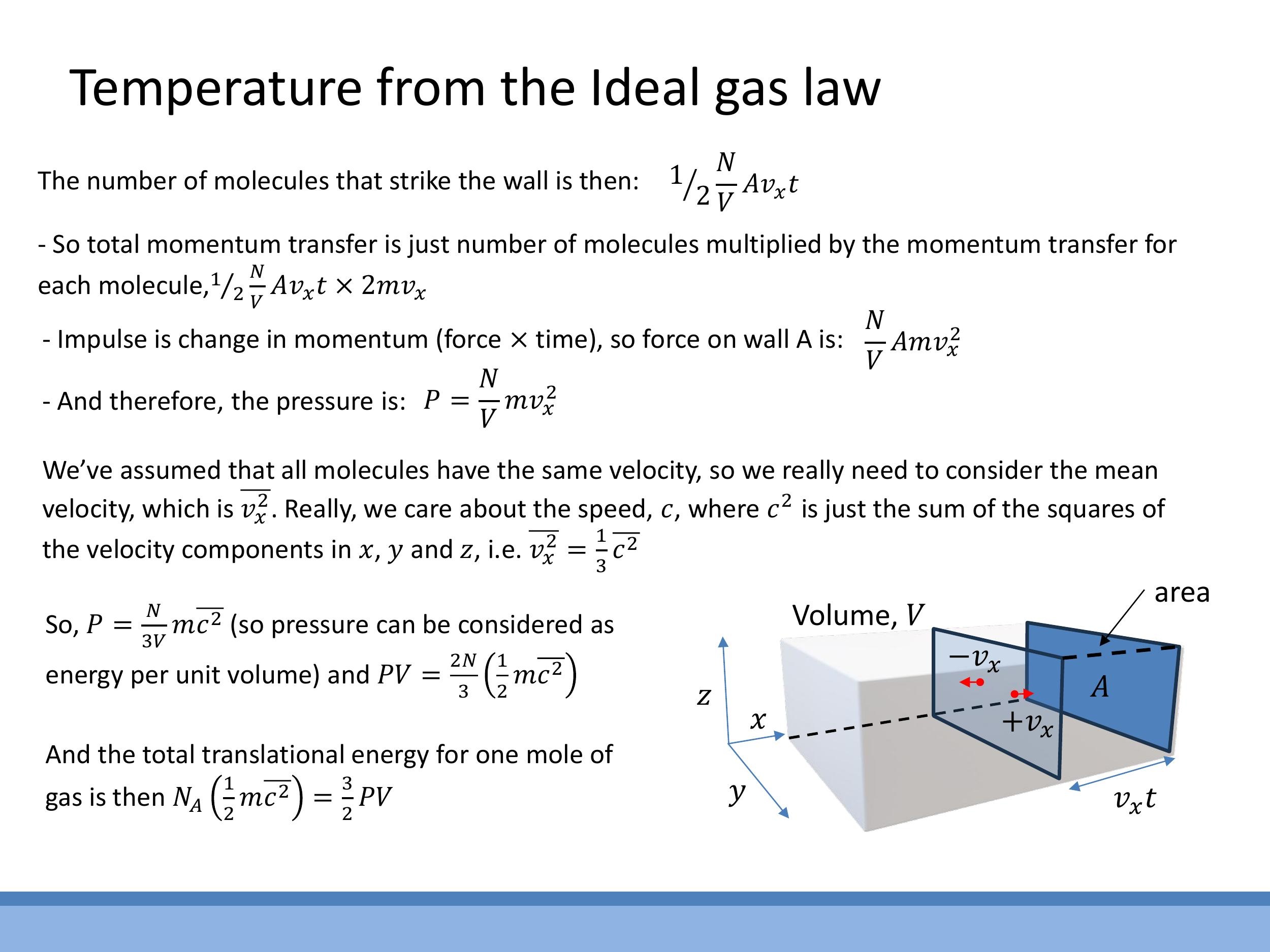

To generalise beyond motion in a single direction, we consider random three-dimensional motion, where the mean square velocity components are equal: $\overline{v_x^2} = \overline{v_y^2} = \overline{v_z^2}$. The mean square speed $\overline{c^2}$ is the sum of these components, so $\overline{v_x^2} = \frac{1}{3} \overline{c^2}$. Substituting this into the pressure equation yields $P = \frac{N}{3V} m \overline{c^2}$. Rearranging this expression, we find $PV = \frac{2N}{3}\left(\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2}\right)$, which highlights pressure as a measure of energy density.

# 2) Identifying temperature with average kinetic energy

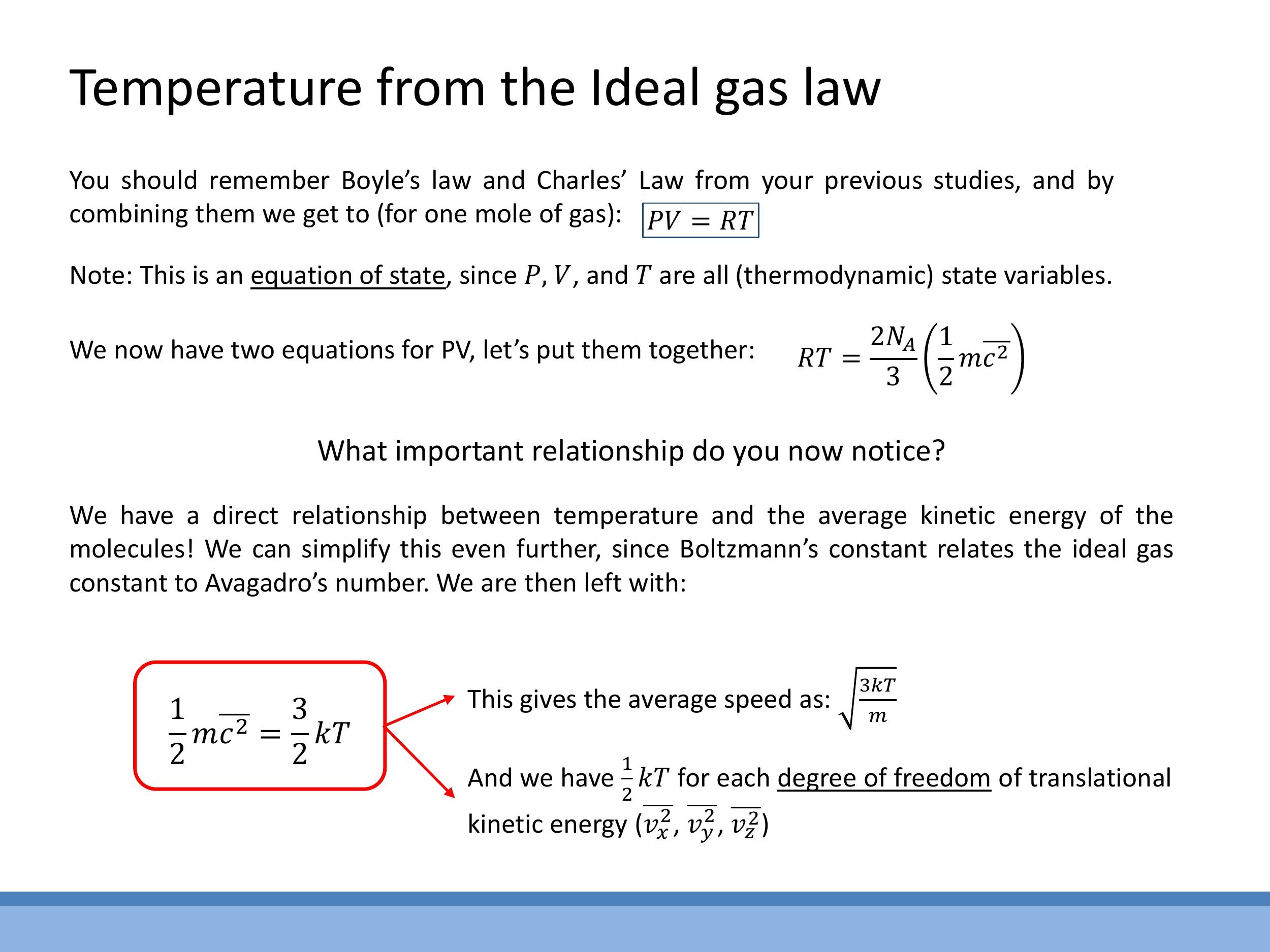

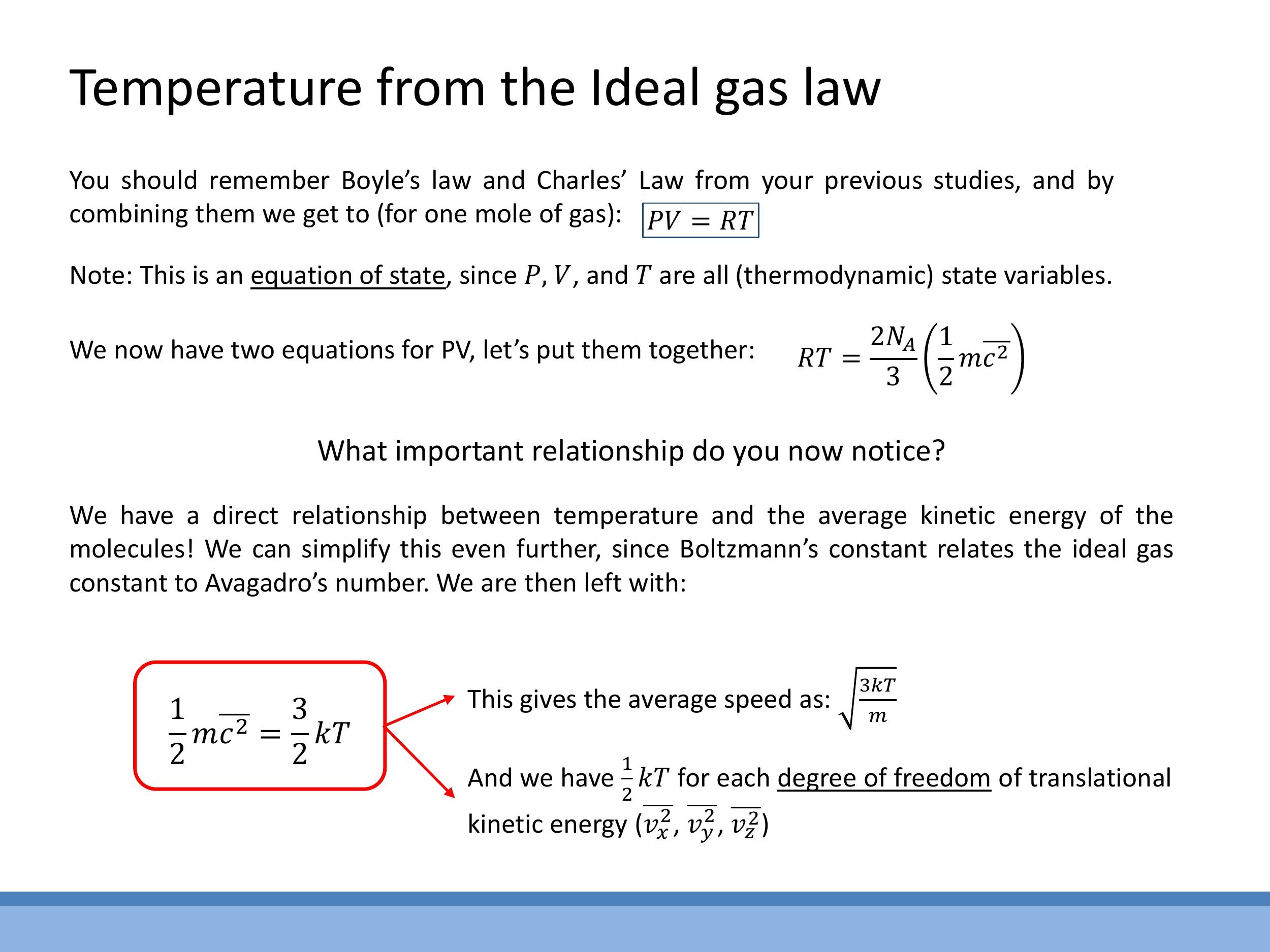

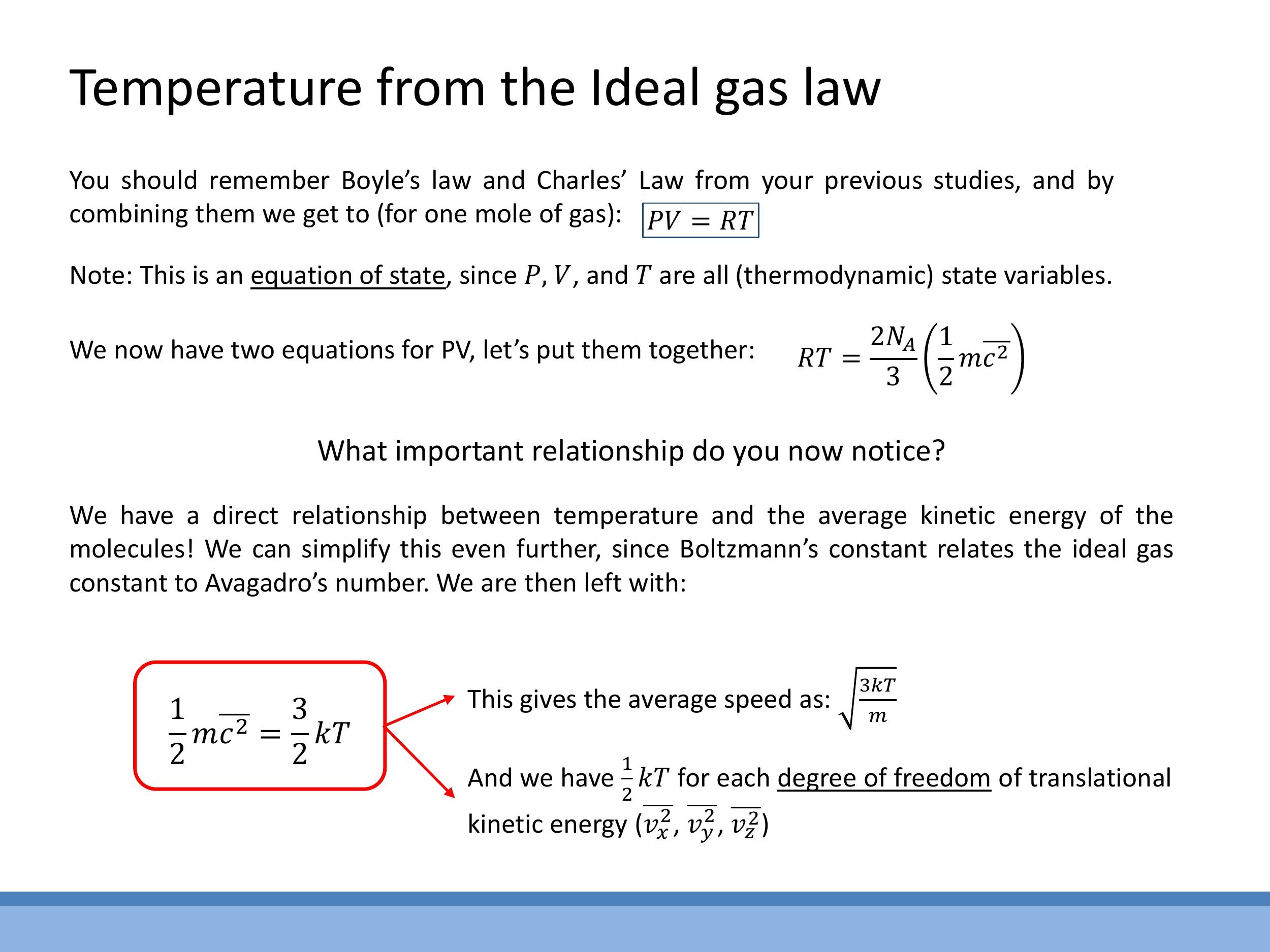

The Ideal Gas Law, $PV = RT$ for one mole of gas, serves as a fundamental equation of state, relating the macroscopic state variables of pressure ($P$), volume ($V$), and absolute temperature ($T$).

By equating the two expressions for $PV$ derived from kinetic theory and the Ideal Gas Law (for one mole, where $N = N_A$), we establish a crucial link: $RT = \frac{2N_A}{3}\left(\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2}\right)$. Using Boltzmann's constant, $k = \frac{R}{N_A}$, which relates the ideal gas constant to Avogadro's number, this expression simplifies to the fundamental relationship between average translational kinetic energy per particle and absolute temperature: $\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2} = \frac{3}{2} kT$. This result indicates that the average speed of gas particles is $\overline{c} = \sqrt{\frac{3kT}{m}}$. Therefore, temperature is directly proportional to the average translational kinetic energy of the gas particles.

# 3) Equipartition and degrees of freedom: “½ kT per way to move”

The equipartition theorem states that, at thermal equilibrium, each quadratic degree of freedom of a system contributes an average energy of $\frac{1}{2} kT$. A degree of freedom refers to an independent way a particle can store energy, typically associated with translational, rotational, or vibrational motion. For a monatomic ideal gas, there are three translational degrees of freedom (motion along $x$, $y$, and $z$ axes), leading to a total average translational energy of $3 \times \frac{1}{2} kT = \frac{3}{2} kT$. Diatomic molecules, being more complex, can also exhibit rotational motion (typically two quadratic degrees of freedom for a linear molecule) and, at higher temperatures, vibrational modes (each contributing two quadratic degrees of freedom, one for kinetic and one for potential energy). The contribution of these additional modes to the total energy depends on temperature, as higher temperatures "unlock" modes whose energy spacings become thermally accessible.

# 4) Building the thermodynamics vocabulary and the Zeroth Law

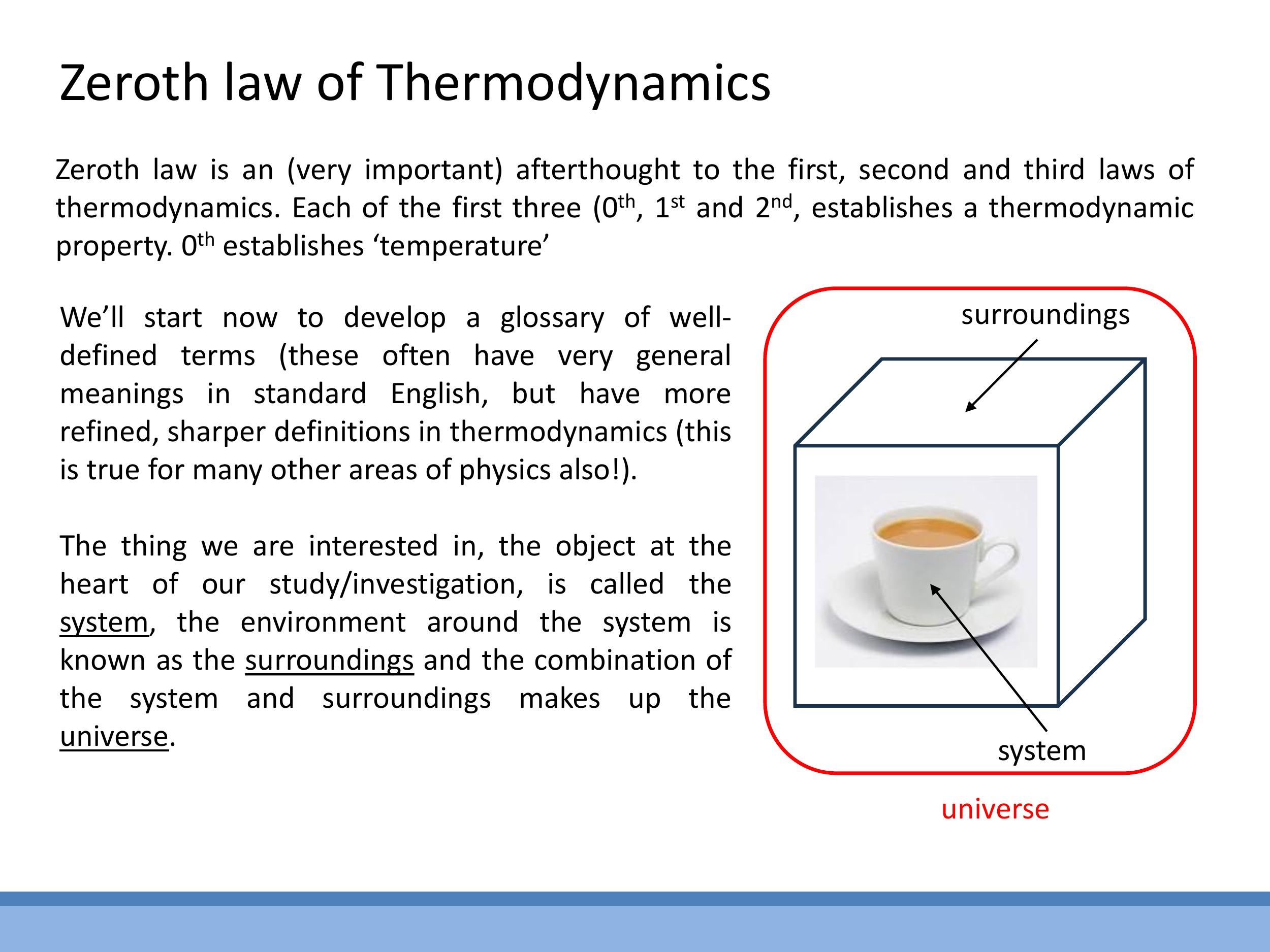

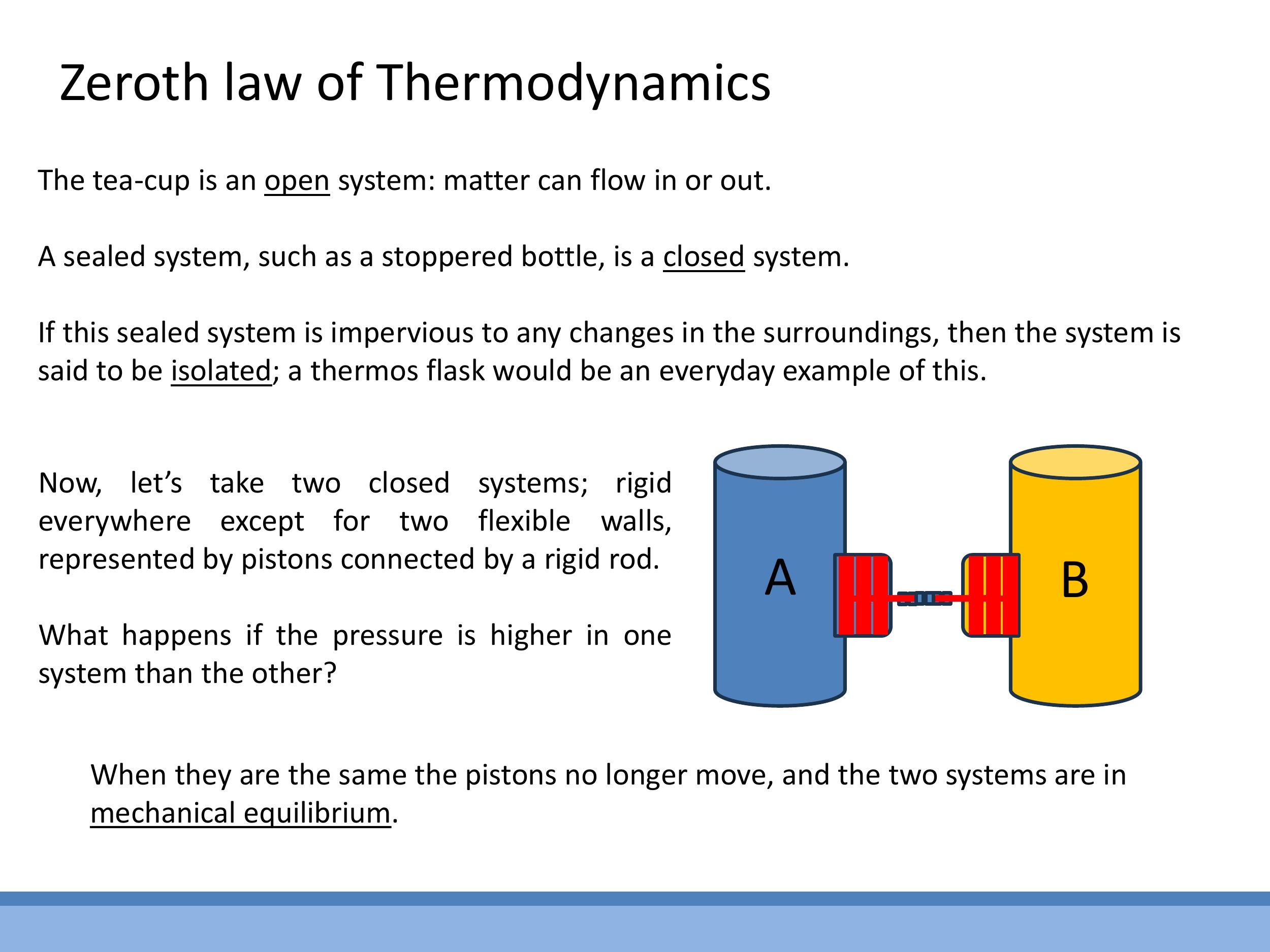

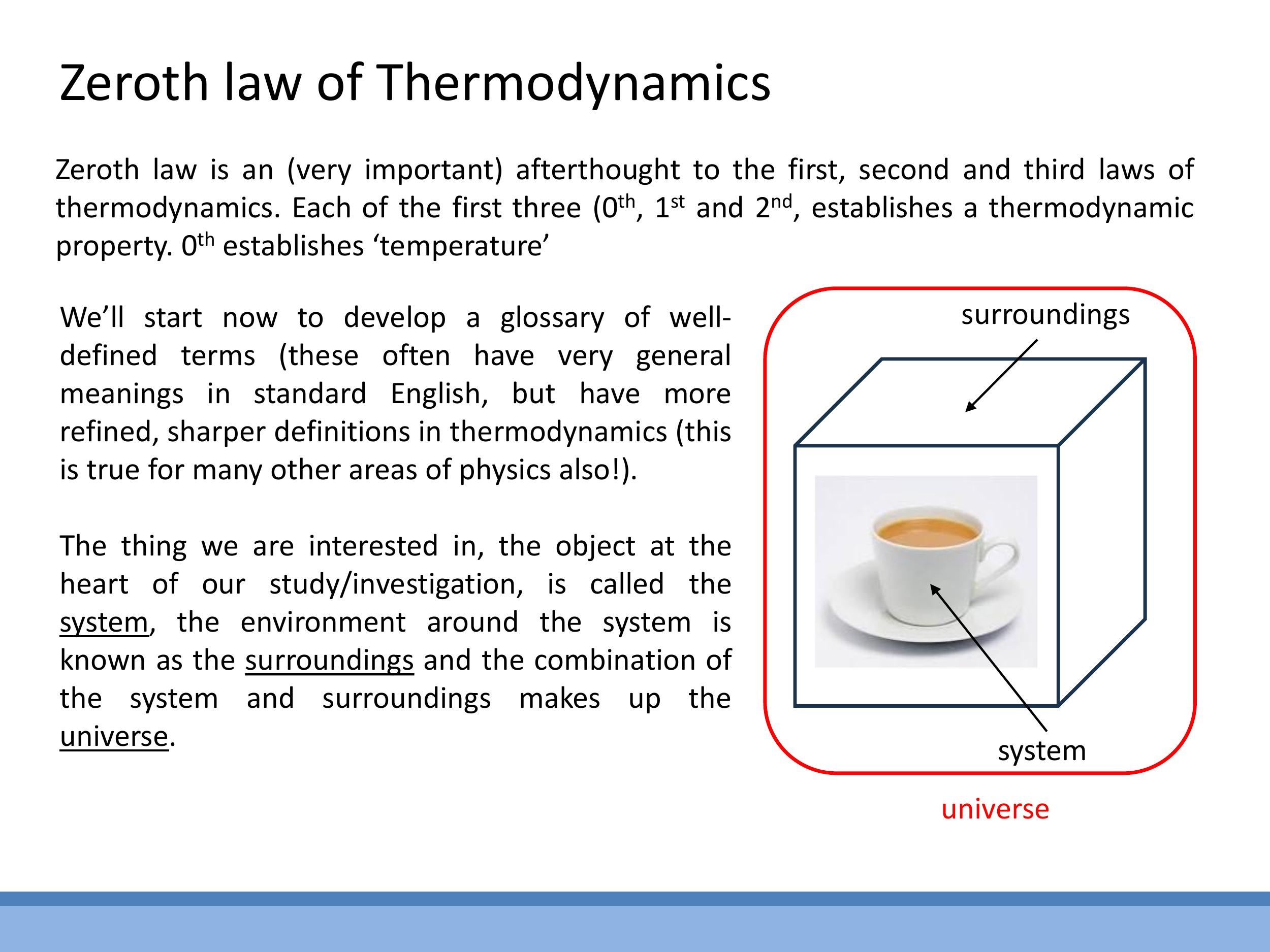

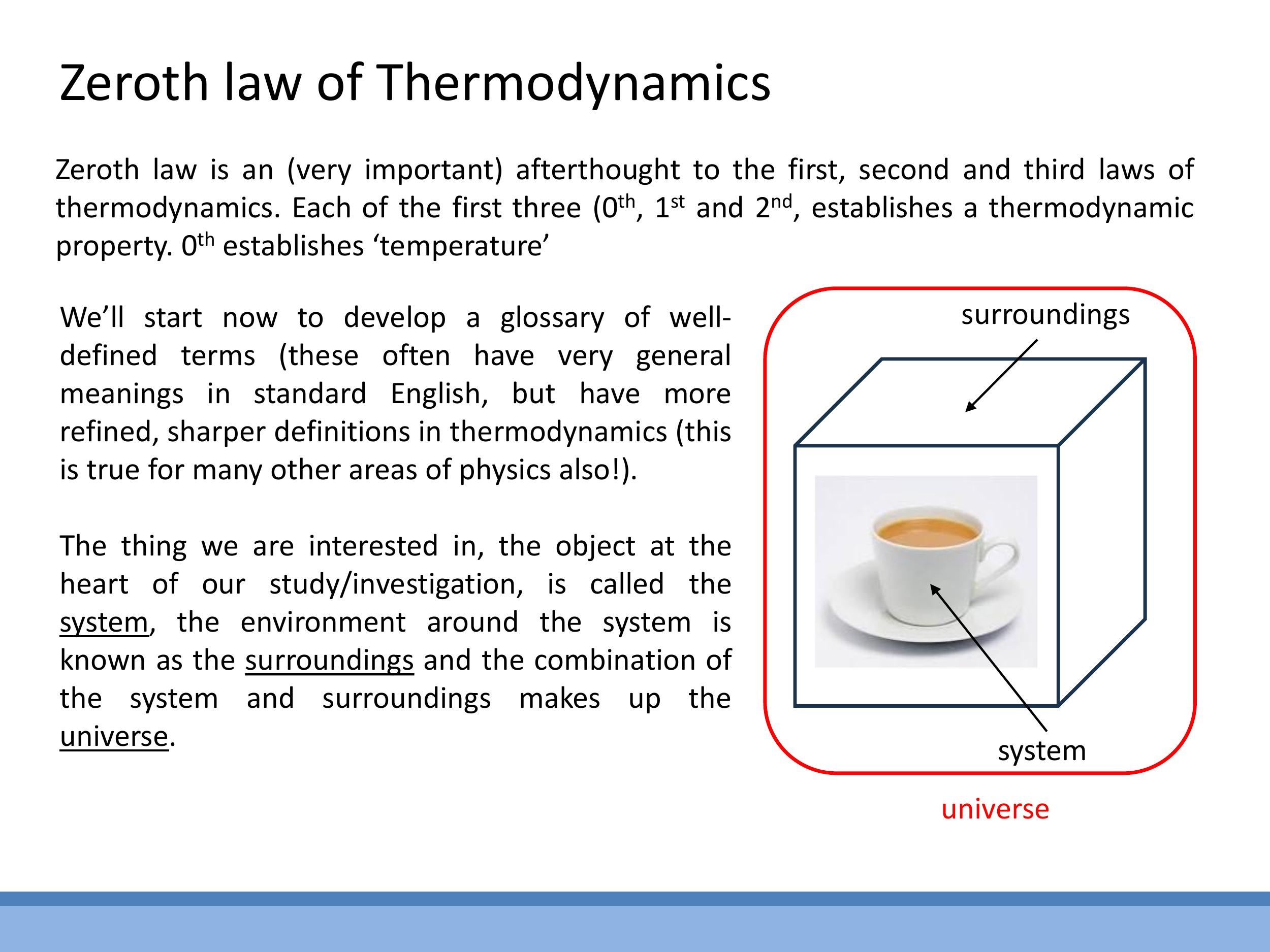

To precisely describe thermodynamic interactions, a set of defined terms is necessary. A system is the specific part of the universe under study, such as a cup of hot tea. The surroundings encompass everything else interacting with the system in its immediate vicinity. The universe in a thermodynamic context is the combination of the system and its surroundings. Systems can be classified by their interactions: an open system exchanges both matter and energy with its surroundings (e.g., an open teacup); a closed system exchanges energy but not matter (e.g., a stoppered bottle); and an isolated system exchanges neither matter nor energy (e.g., an ideal thermos flask).

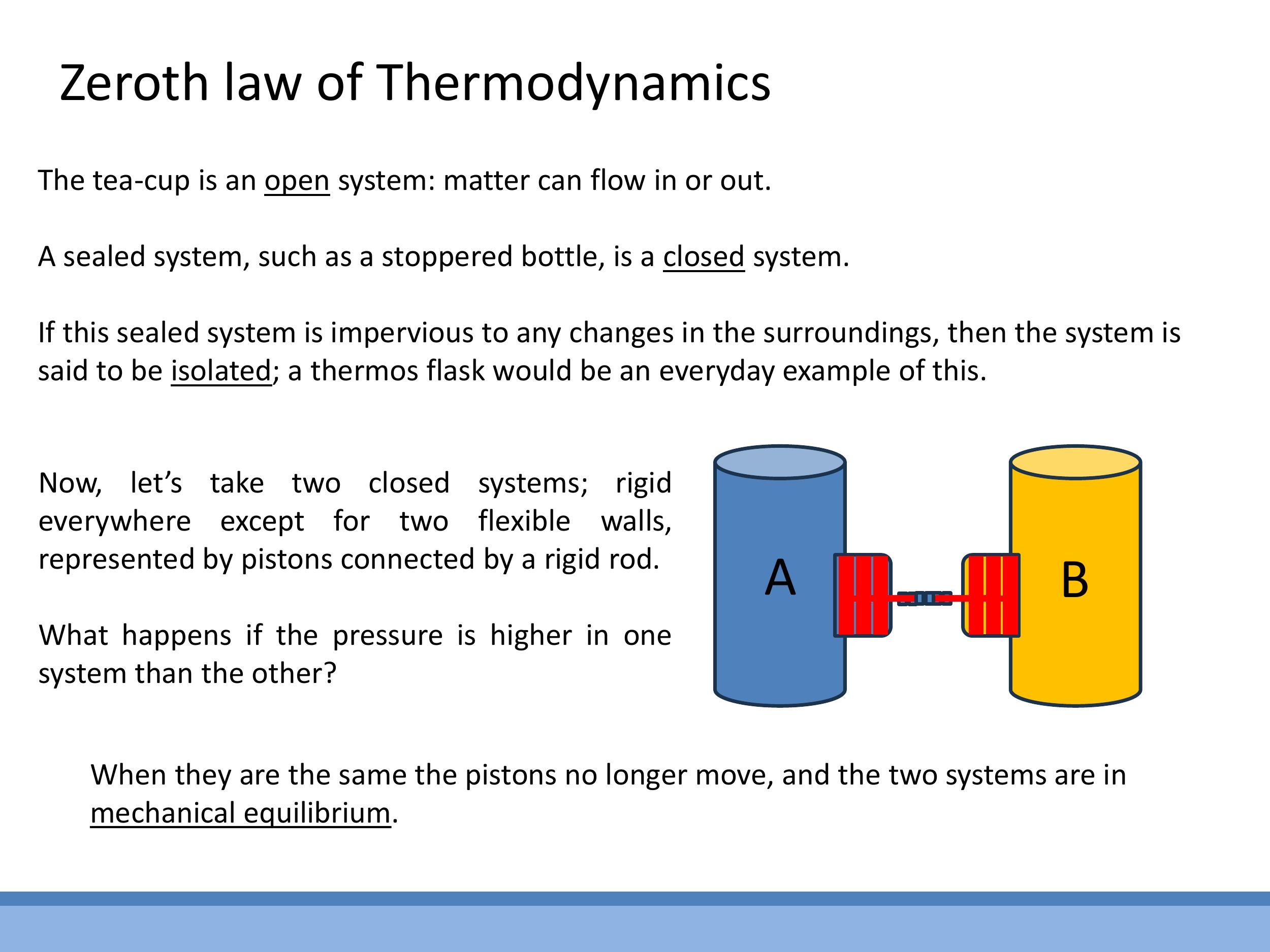

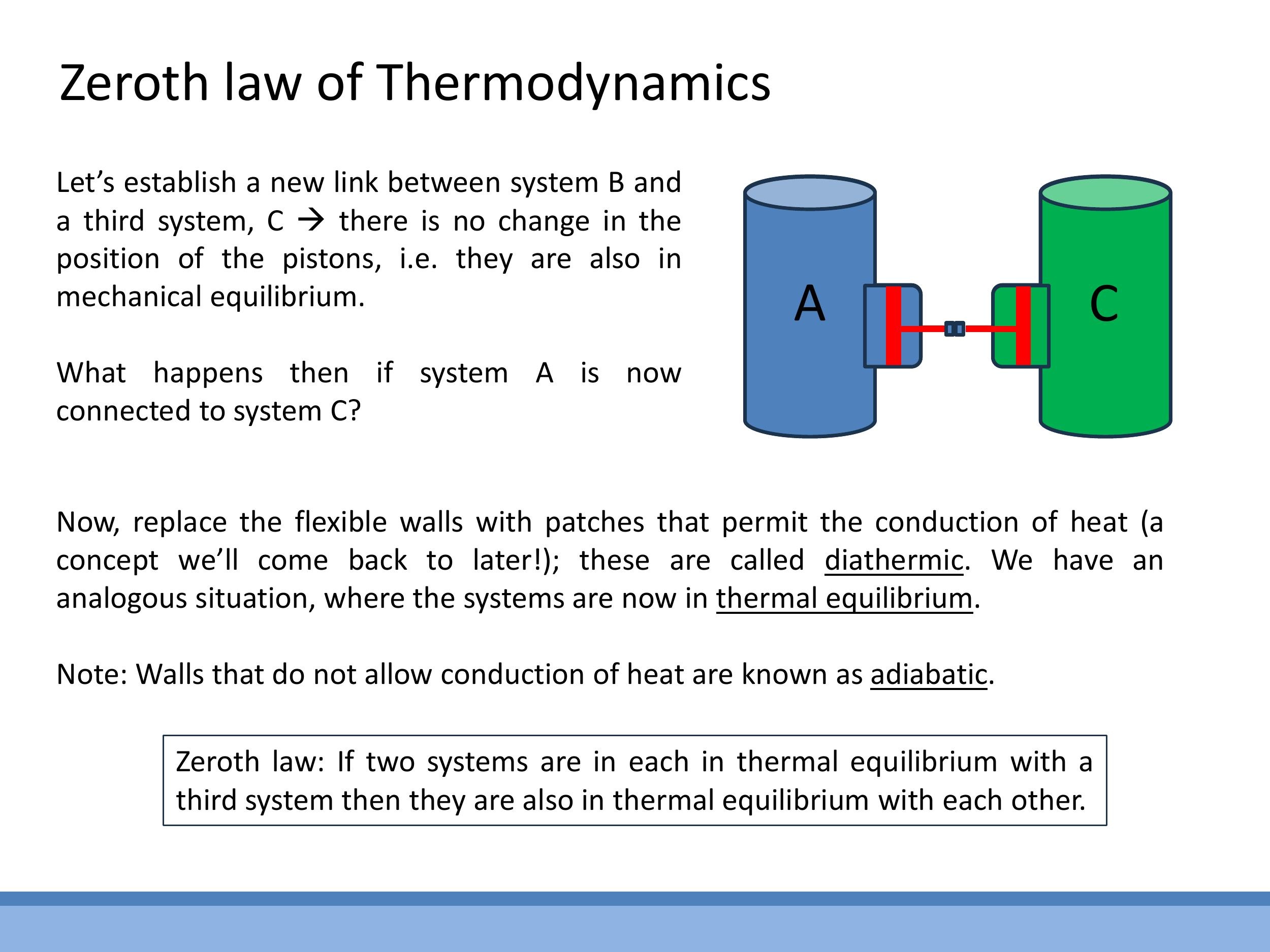

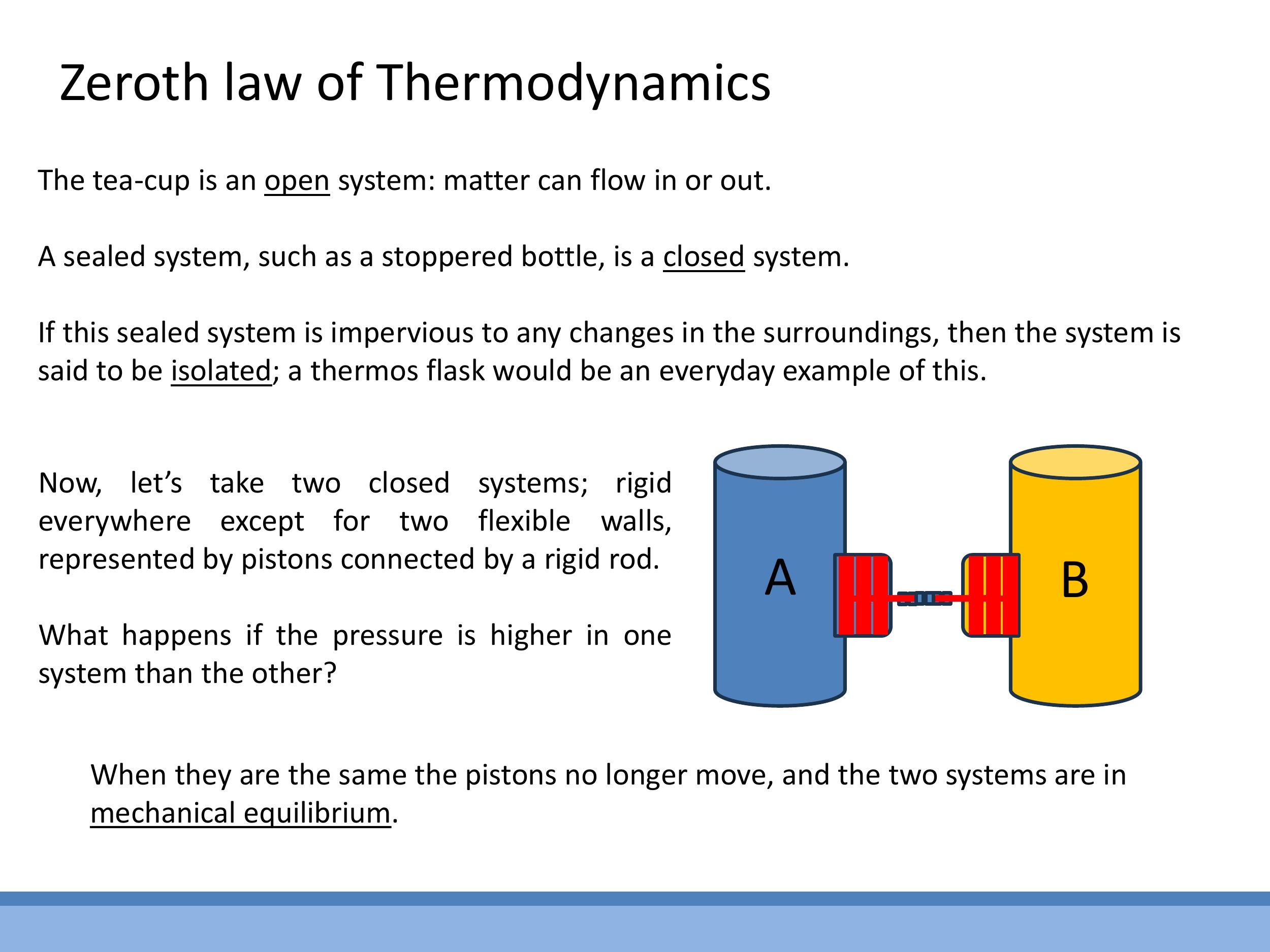

The concept of equilibrium can be understood through analogies. In mechanical equilibrium, two pressurised vessels connected by a movable piston will not experience net movement if their pressures are equal, illustrating a transitive property.

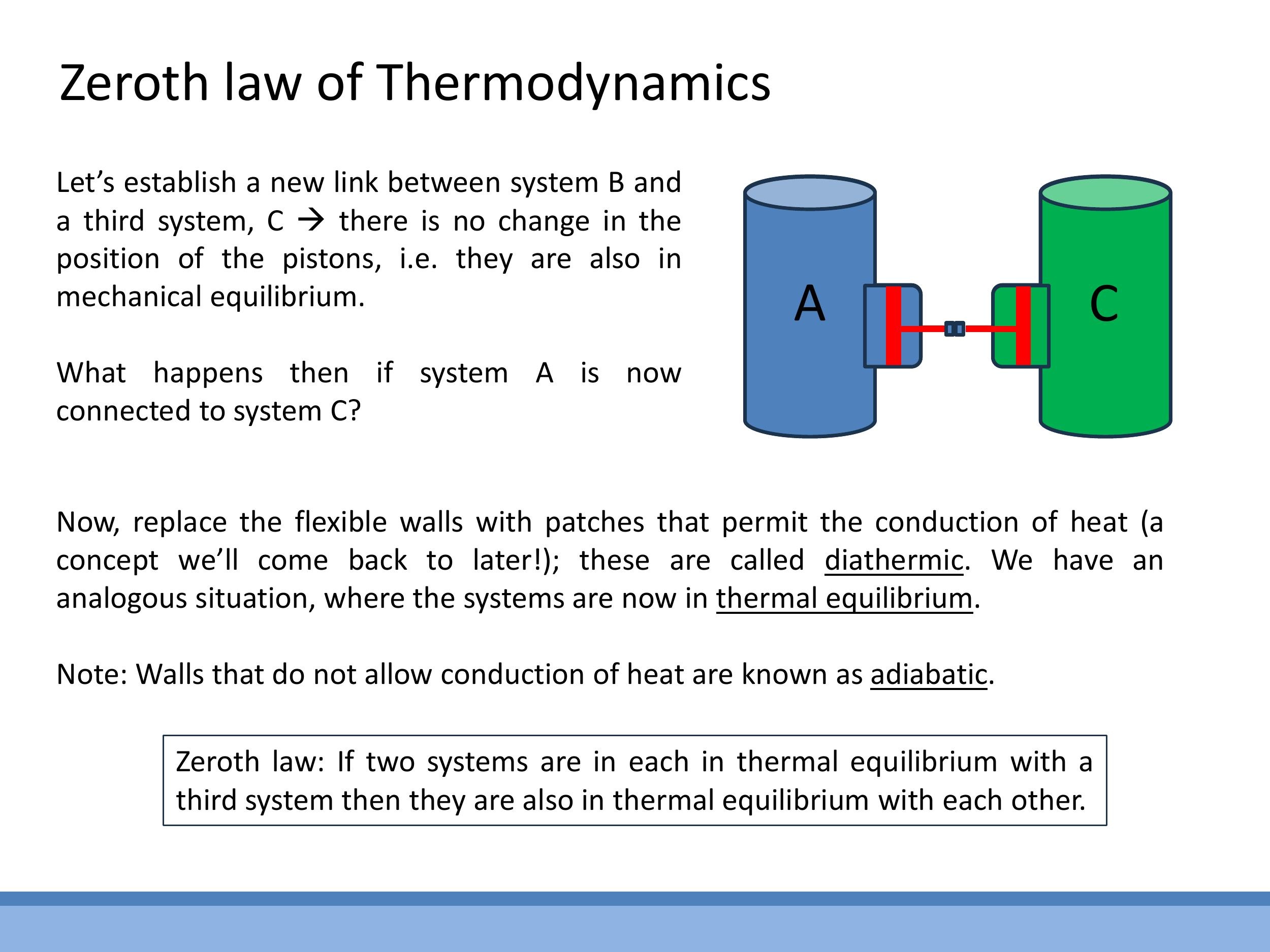

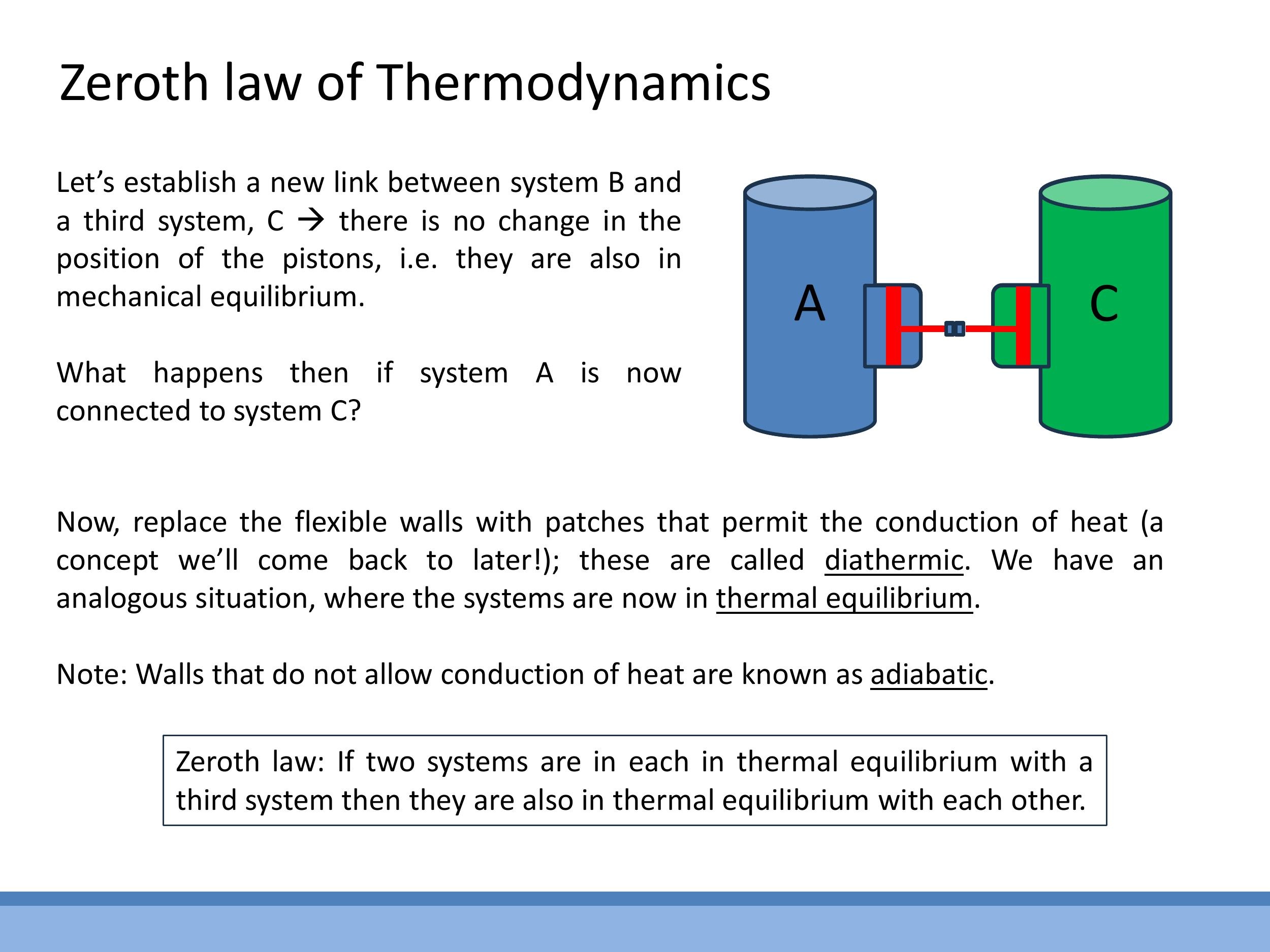

This analogy extends to thermal equilibrium diathermic walls (which permit heat flow) and no net energy flows between them, they are in thermal equilibrium, implying they have the same "temperature." Conversely, adiabatic walls prevent heat flow, effectively isolating a system.

The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics formalises the concept of temperature and underpins all thermometry:

Zeroth law: If two systems are in each in thermal equilibrium with a third system then they are also in thermal equilibrium with each other.

This law enables the consistent measurement of temperature across different materials and systems by ensuring that a thermometer (the third system) can accurately compare the temperatures of any two other systems placed in thermal contact with it.

# 5) Temperature scales and absolute temperature (Kelvin)

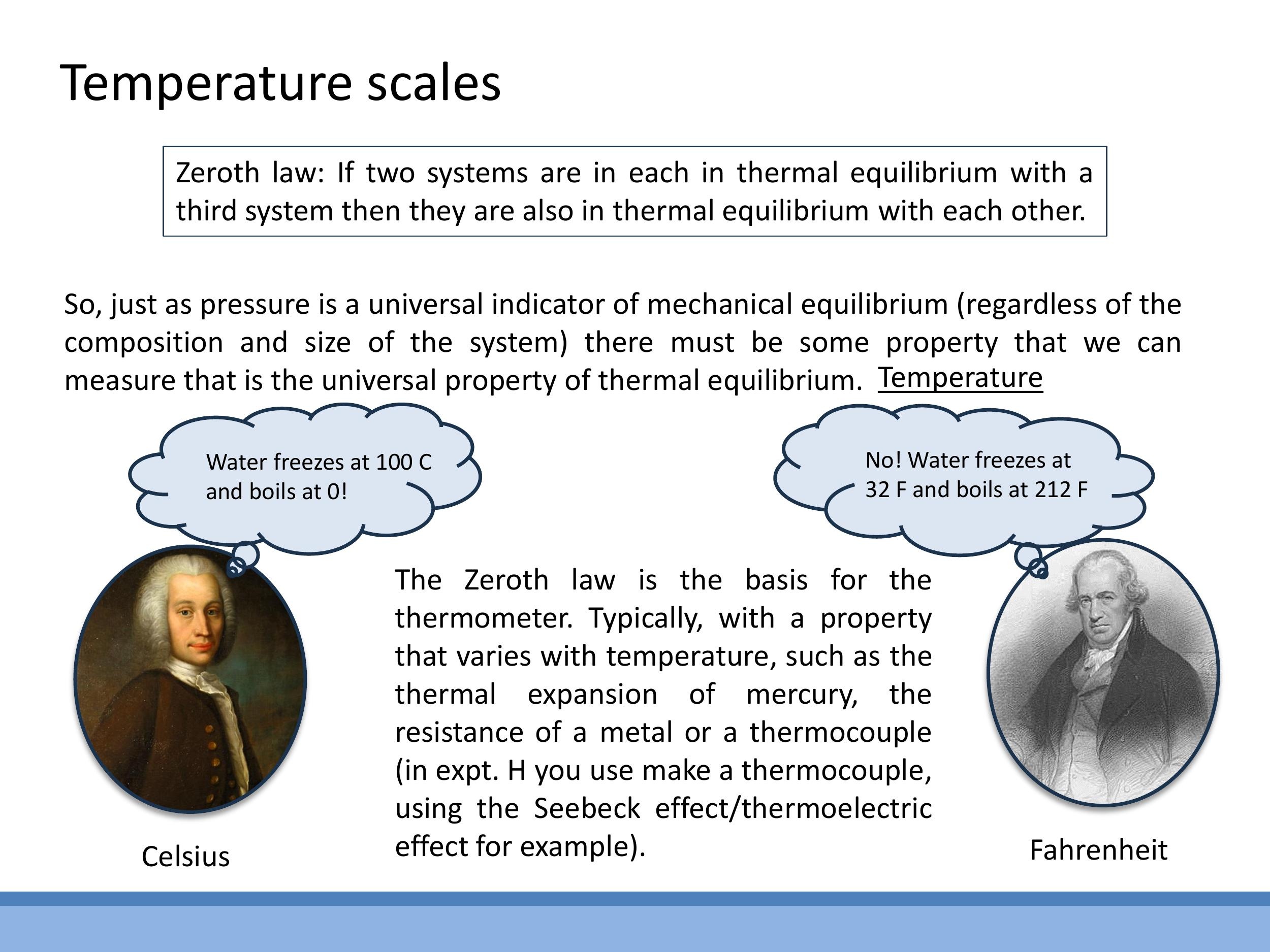

Historical temperature scales, such as Celsius (originally defined with water boiling at $0^\circ\text{C}$ and freezing at $100^\circ\text{C}$) and Fahrenheit (based on human body temperature and a reproducible cold mixture), were initially arbitrary.

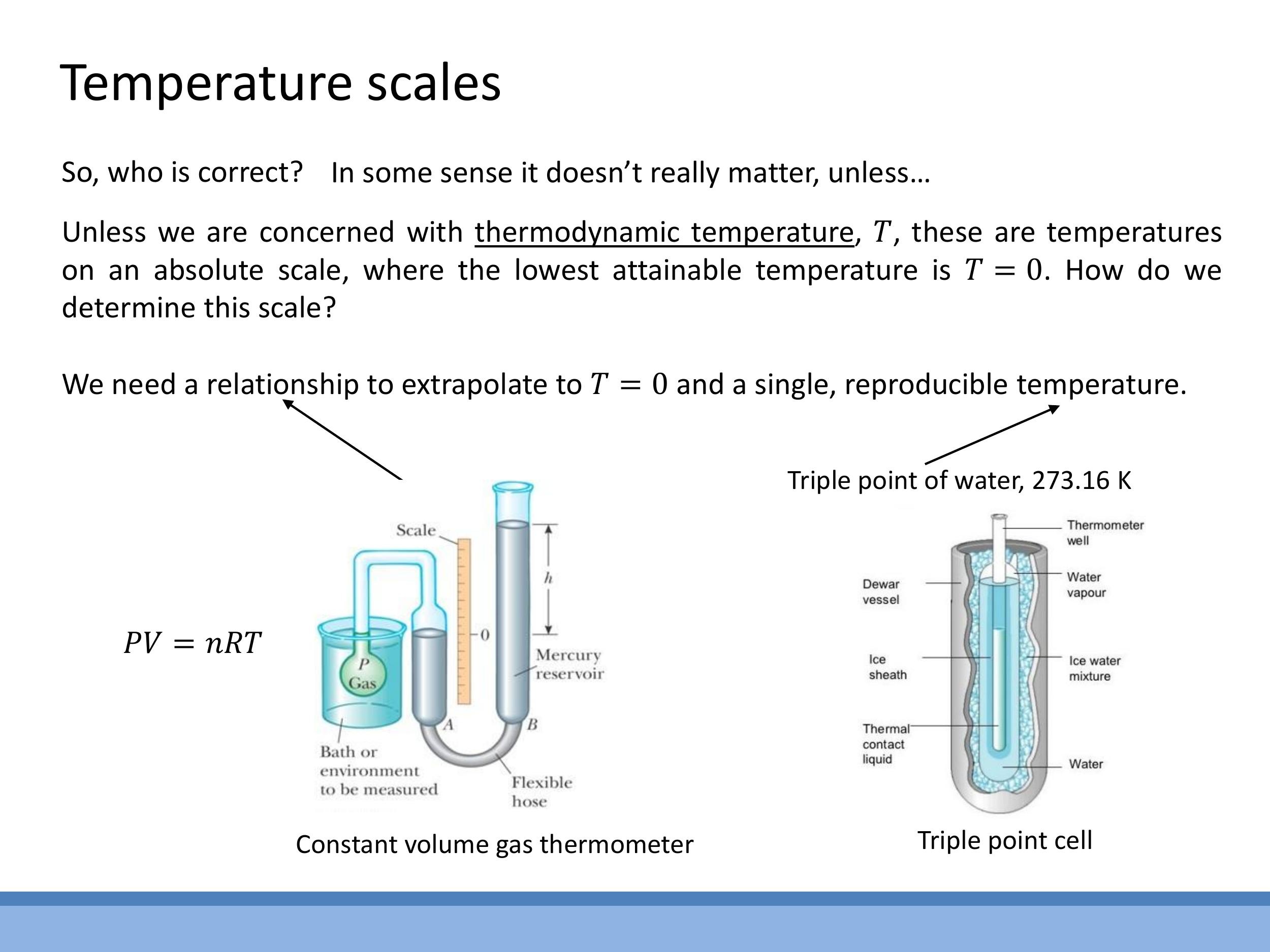

However, for fundamental thermodynamic analysis, an absolute thermodynamic temperature scale is required, where $T=0 \, \text{K}$ represents absolute zero, the lowest possible temperature. The Kelvin (K) scale is the standard SI absolute scale, sharing the same step size as Celsius but shifted such that $0^\circ\text{C}$ corresponds to $273.15 \, \text{K}$. The Rankine scale is the Fahrenheit-based equivalent absolute scale.

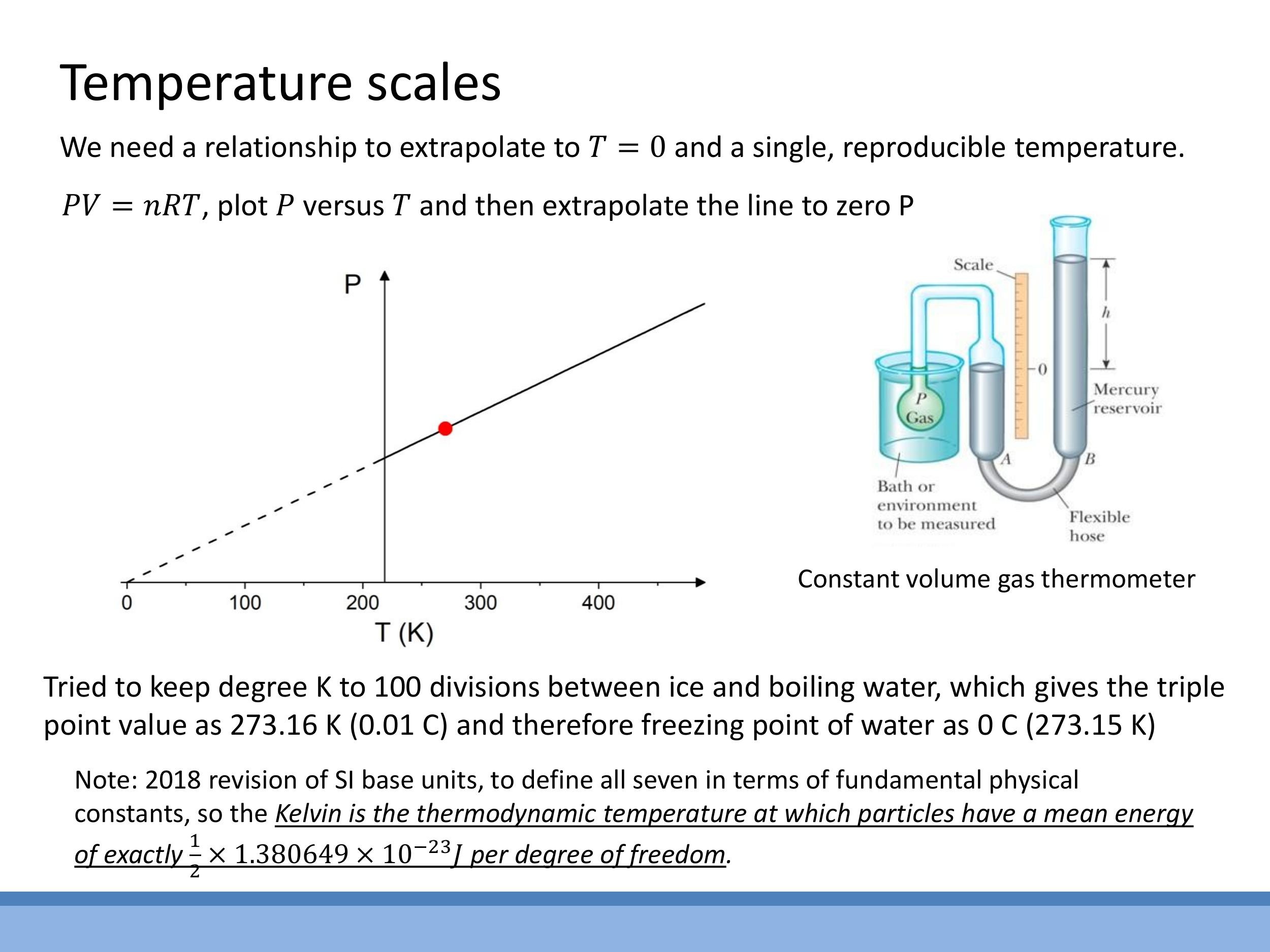

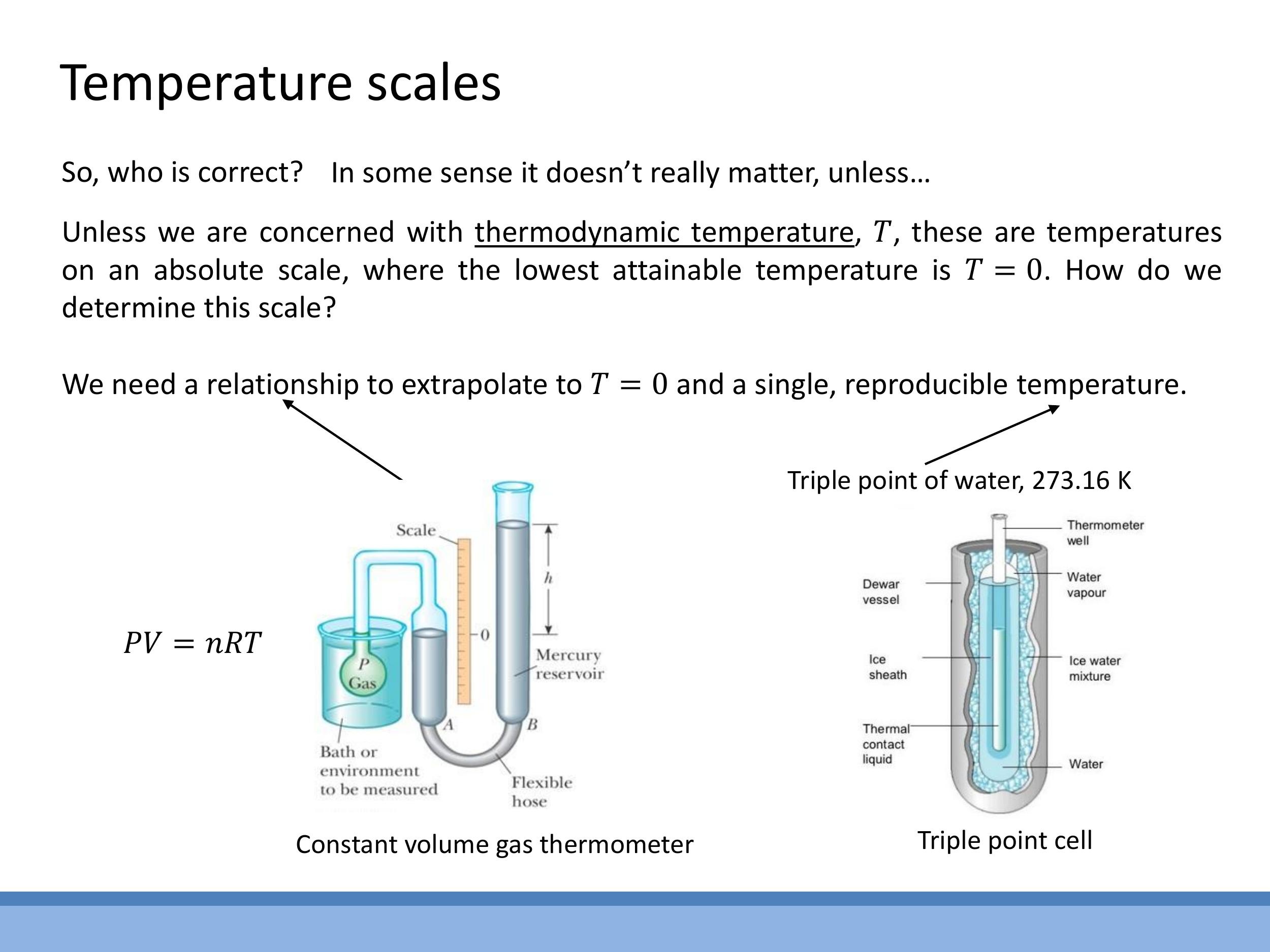

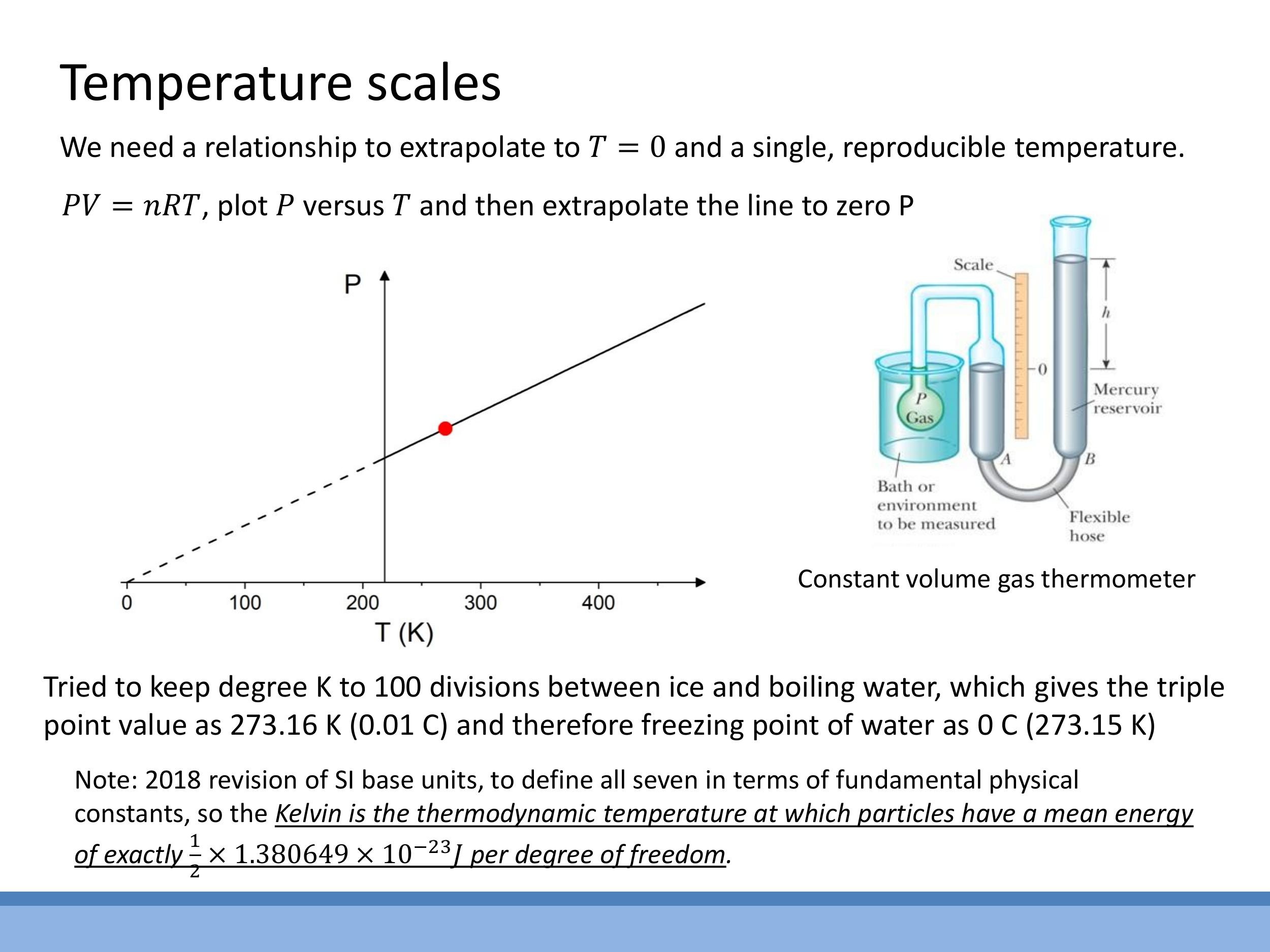

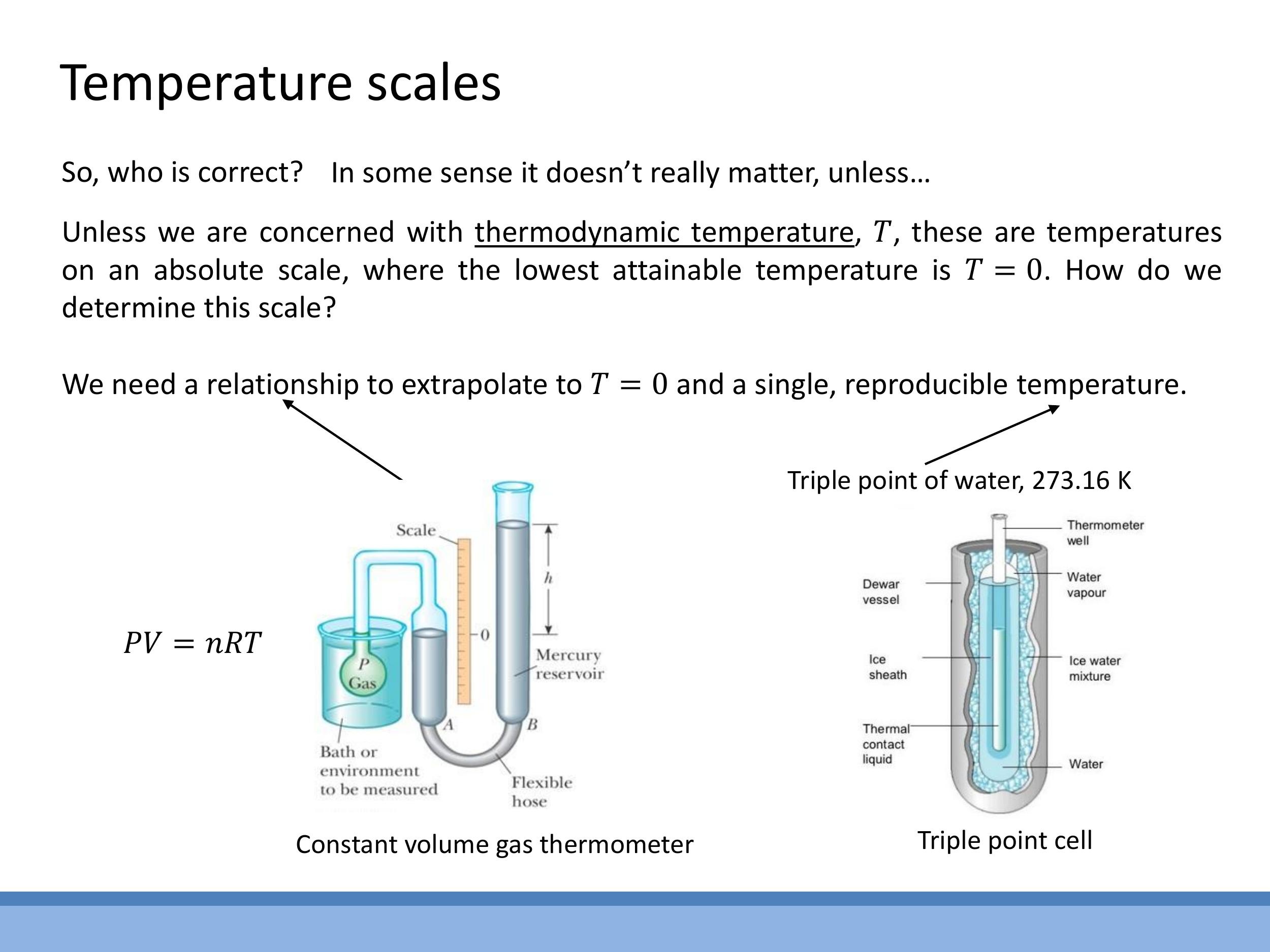

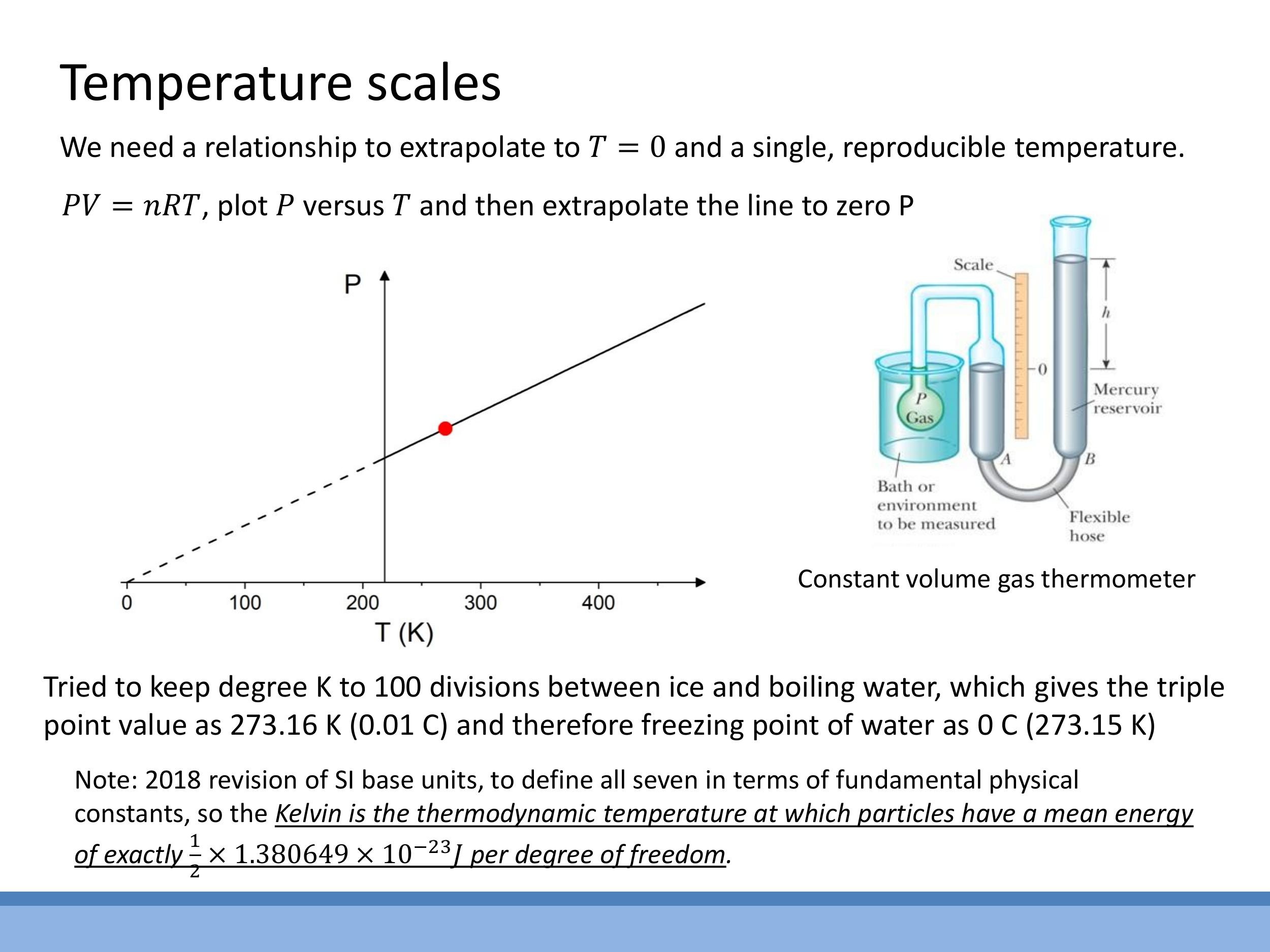

An absolute scale is measured using a constant-volume gas thermometer triple point of water, where solid, liquid, and gas phases coexist in equilibrium, defined as $273.16 \, \text{K} $ ($ 0.01^\circ\text{C} $). Unlike freezing or boiling points, which vary with pressure, the triple point is unique. By measuring pressure at the triple point and other temperatures, a linear $ P $-$ T $ plot can be generated. Extrapolating this linear relationship to $ P \rightarrow 0 $ identifies absolute zero, $ T \rightarrow 0 \, \text{K} $, where particle motion and thus pressure theoretically vanish. In 2018, the SI definition of the Kelvin was revised, directly linking temperature to energy by fixing the numerical value of Boltzmann's constant $ k$.

# 6) Microscopic temperature: Boltzmann factor and distributions

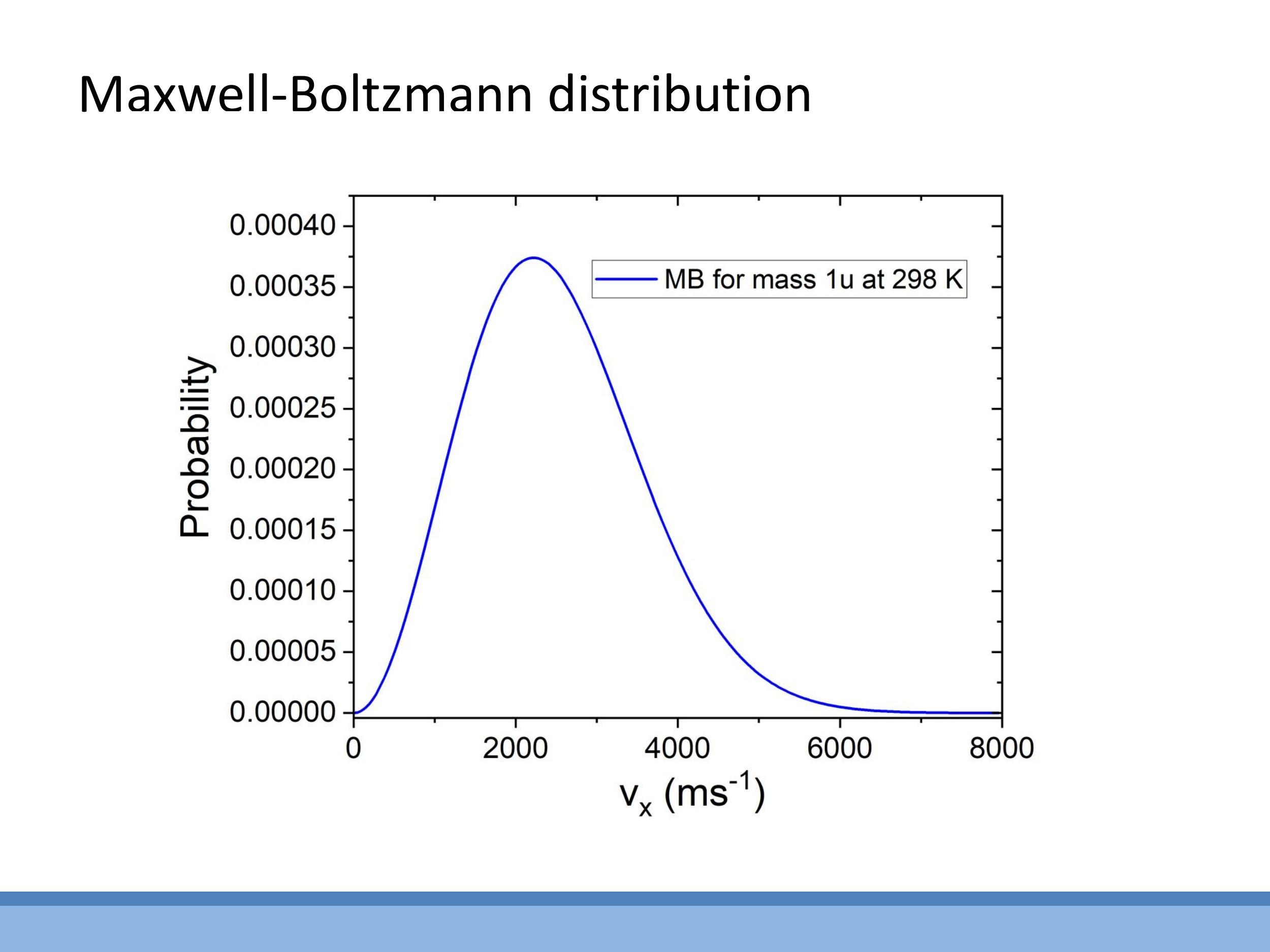

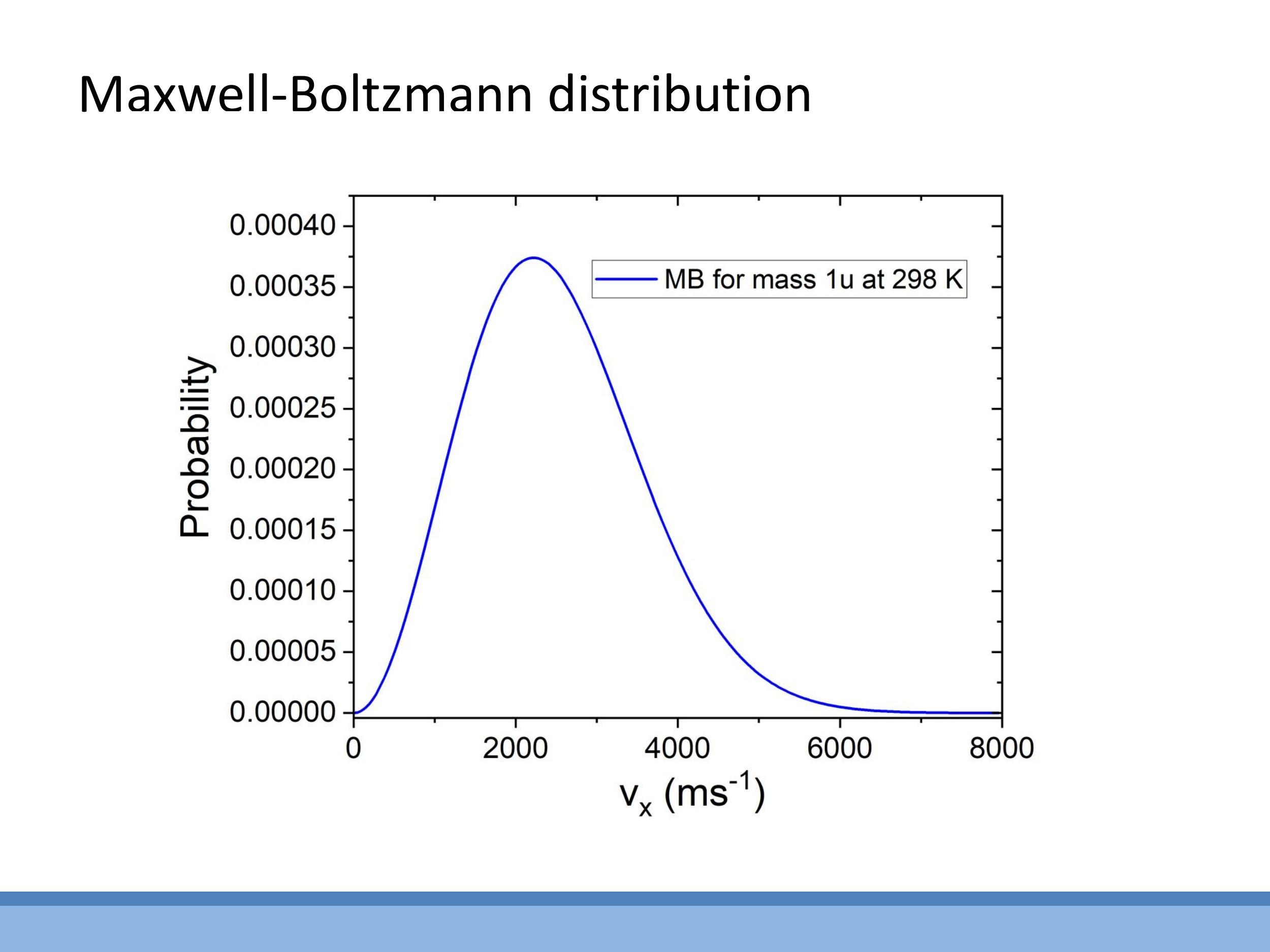

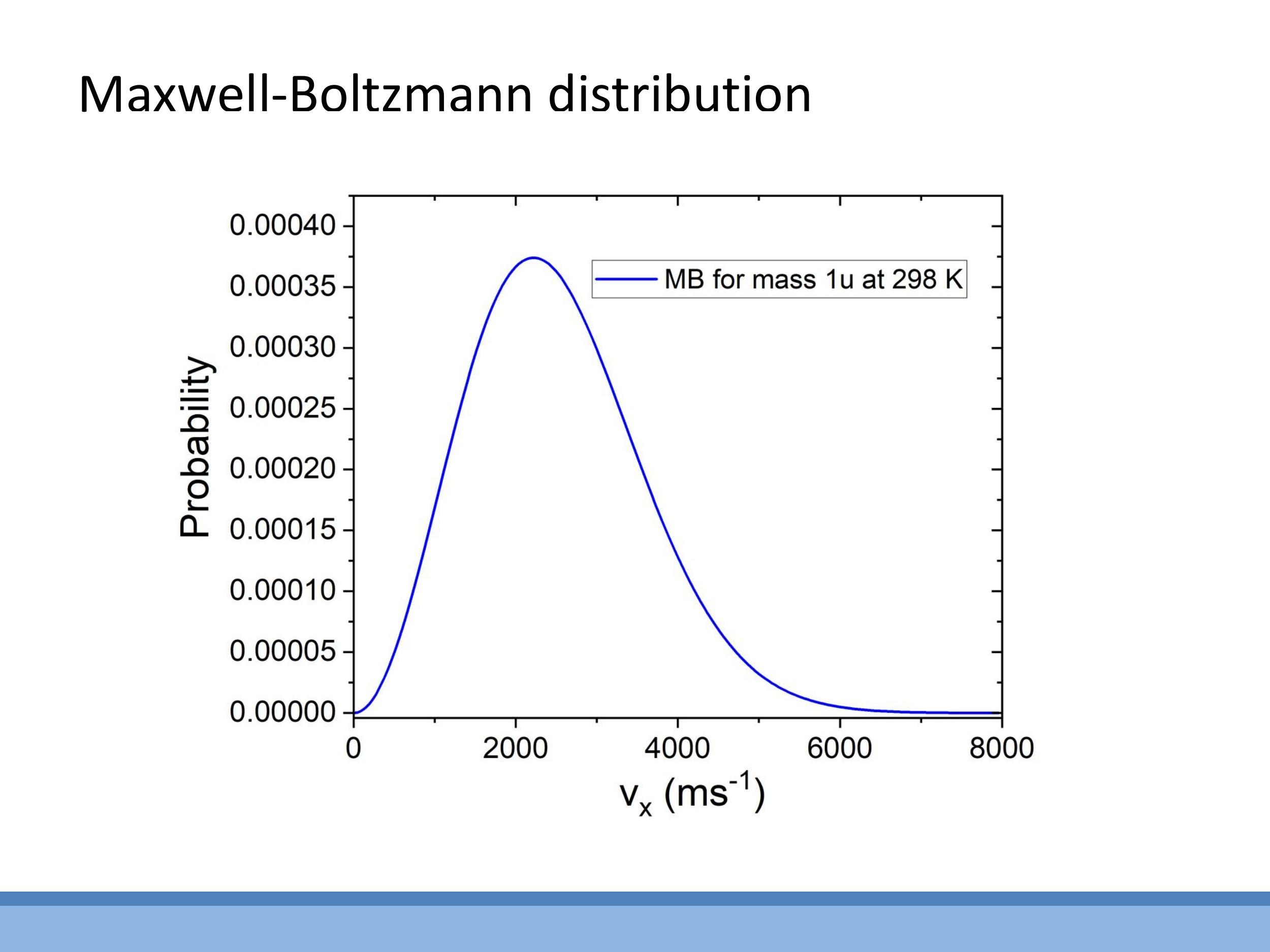

Beyond average kinetic energy, a deeper microscopic understanding of temperature involves the distribution of particle speeds and energies. The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution describes the spread of speeds and velocities among gas particles at a given temperature, with the shape of this distribution changing with temperature and particle mass.

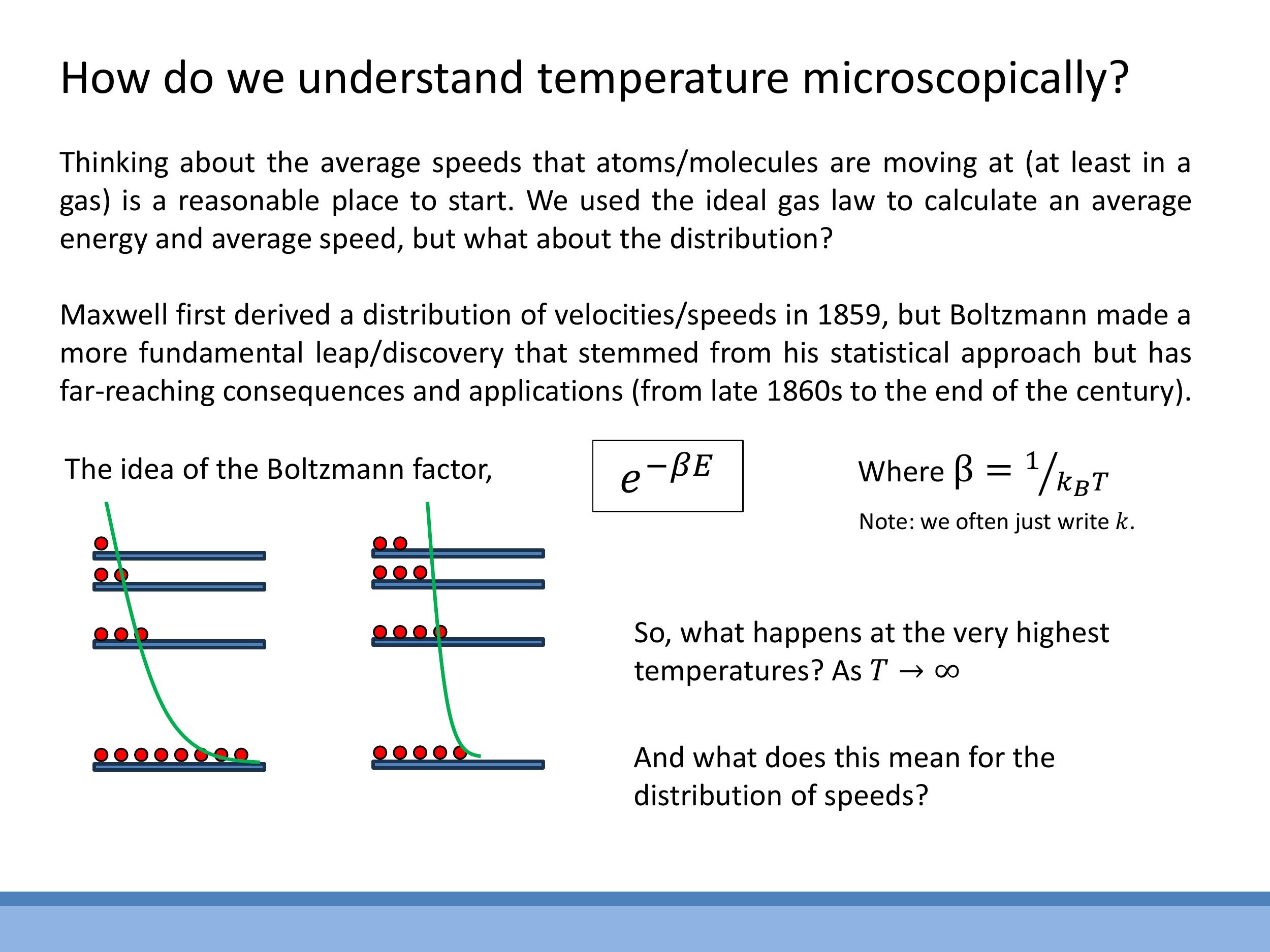

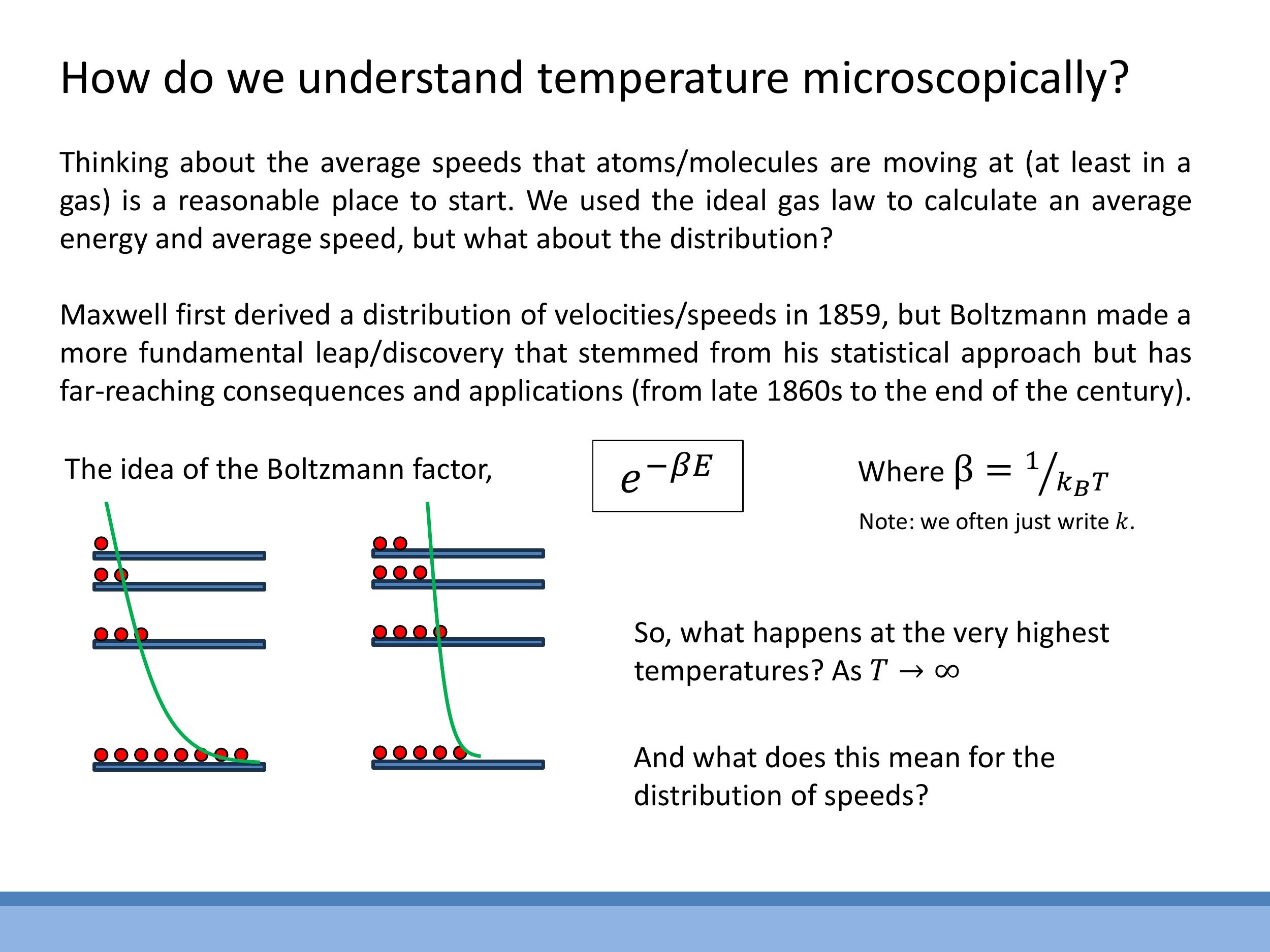

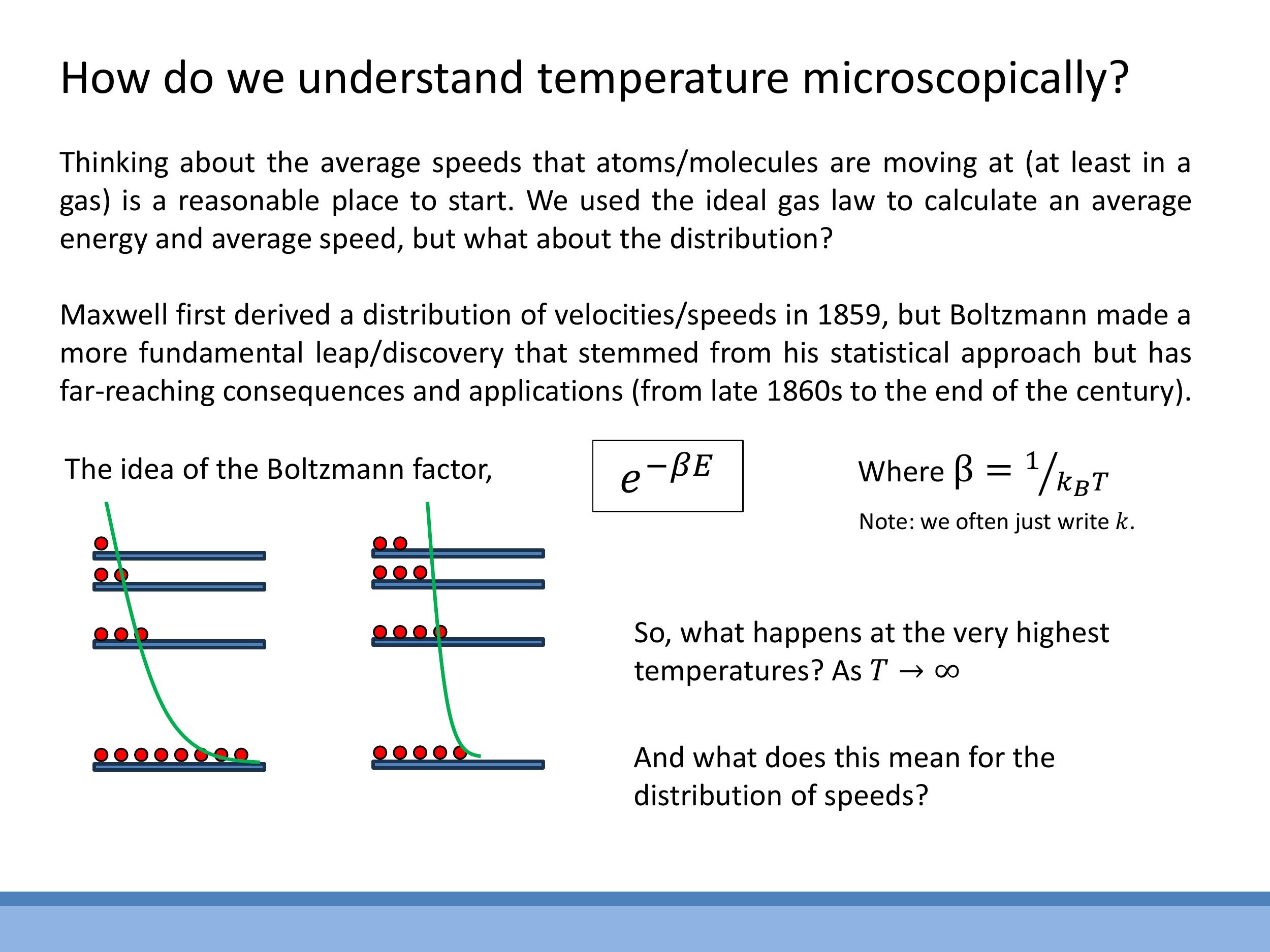

The core concept that governs these distributions is the Boltzmann factor, $e^{-\beta E}$, where $\beta = \frac{1}{kT}$. This factor represents the probability weight for a particle or system to occupy an energy state $E$ at a given temperature $T$. An analogy of "balls on shelves" illustrates this: the shelves represent quantised energy levels, and the balls represent particles. At lower temperatures, most particles occupy lower energy levels (bottom shelves). As temperature increases, the population spreads across higher energy levels, reflecting the increased thermal energy.

As $T \rightarrow \infty$ (meaning $\beta \rightarrow 0$), the Boltzmann factor approaches $1$, indicating that all energy levels become equally populated. This microscopic view of temperature, describing how energy is distributed among available states, forms the basis for understanding more advanced thermodynamic concepts, such as population inversion, which refers to a non-equilibrium state where higher energy levels are more populated than lower ones.

# 7) Bridge back to the demo and forward to next topics

The elastocaloric effect, observed with the elastic band, directly illustrates that doing work on a system can increase its internal energy and temperature, while rapid contraction can cause cooling. These phenomena are explained more fully by concepts of heat, work, and internal energy, which are central to the First Law of Thermodynamics. Future lectures will delve into the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics, providing a comprehensive energy-accounting picture that will allow a more complete understanding of the elastic band demonstration.

Key takeaways

- Kinetic theory to temperature: Pressure arises from molecular momentum transfer, yielding $PV = \frac{2N}{3}\left(\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2}\right)$. This equates to $\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2} = \frac{3}{2} kT$, indicating that temperature is directly proportional to the average translational kinetic energy per particle, with an average speed of $\overline{c} = \sqrt{\frac{3kT}{m}}$. The equipartition theorem states that each quadratic degree of freedom contributes an average energy of $\frac{1}{2} kT$; monatomic gases, with three translational degrees of freedom, thus have $\frac{3}{2} kT$ of translational energy.

- Thermodynamics language: Key terms include system, surroundings, and universe, which combine to describe the scope of study. Systems are classified as open (exchanging matter and energy), closed (exchanging energy only), or isolated (exchanging neither). Walls can be diathermic (permitting heat flow) or adiabatic (preventing heat flow). The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics, which states that if two systems are each in thermal equilibrium with a third, they are in thermal equilibrium with each other, underpins the concept of temperature and the operation of thermometers.

- Absolute temperature: The Kelvin scale is an absolute temperature scale with $T = 0 \, \text{K} $ as absolute zero. It is established via constant-volume gas thermometry, using the triple point of water ($ 273.16 \, \text{K}$) as a reproducible reference point and extrapolating pressure to zero to find absolute zero. The modern SI definition of the Kelvin fixes Boltzmann's constant, directly linking temperature to energy.

- Microscopic view: Maxwell-Boltzmann distributions describe the spread of particle speeds. The Boltzmann factor, $e^{-\beta E}$ with $\beta = \frac{1}{kT}$, is a fundamental weight that quantifies how temperature influences the occupancy of different energy states.

## Lecture 5: Thermal Energy of Gases (part 2) and the Zeroth Law

### 0) Orientation, live demo, and quick recap

A live demonstration of the elastocaloric effect, using an elastic band, illustrates fundamental thermodynamic principles. When rapidly stretched, the band warms; holding it stretched allows it to cool to ambient temperature; and a sudden release causes it to cool. Students observe these subtle temperature changes by touching the band to their lips, which are sensitive to small thermal differences. This demonstration intuitively introduces the relationships between work, heat, and internal energy, with a full microscopic explanation reserved for later lectures. Today's session completes the microscopic derivation linking gas particle motion to temperature, introduces the Zeroth Law and precise thermodynamic terminology, places temperature on an absolute (Kelvin) scale, explains its measurement, and offers a glimpse into the microscopic meaning of temperature via the Boltzmann factor. The underlying model for these derivations is the ideal gas, which assumes many identical, non-interacting, point-like particles undergoing elastic collisions and random motion. The very word "gas" derives from "chaos," reflecting this inherent randomness.

## # 1) From wall impacts to pressure: finishing the kinetic-theory link

Pressure, defined as force per unit area, results from the transfer of momentum when gas molecules elastically collide with the container walls.

For a single molecule of mass $m$ with an $x$-component of velocity $v_x$ that collides elastically with a wall, the change in momentum imparted to the wall is $2mv_x$. The number of such collisions on an area $A$ in time $t$ by molecules moving towards the wall is given by $\frac{1}{2}\frac{N}{V} A v_x t$, where $N$ is the total number of molecules and $V$ is the volume. The factor of $\frac{1}{2}$ accounts for, on average, half of the molecules moving in the direction of the wall. The total impulse, which is force multiplied by time, is the product of the number of hits and the momentum change per hit: $\left(\frac{1}{2}\frac{N}{V} A v_x t\right) \times \left(2mv_x\right)$. Dividing this total impulse by time $t$ yields the force on the wall, and further dividing by the area $A$ gives the pressure: $P = \frac{N}{V} m v_x^2$.

To generalise beyond motion in a single direction, we consider random three-dimensional motion, where the mean square velocity components are equal: $\overline{v_x^2} = \overline{v_y^2} = \overline{v_z^2}$. The mean square speed $\overline{c^2}$ is the sum of these components, so $\overline{v_x^2} = \frac{1}{3} \overline{c^2}$. Substituting this into the pressure equation yields $P = \frac{N}{3V} m \overline{c^2}$. Rearranging this expression, we find $PV = \frac{2N}{3}\left(\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2}\right)$, which highlights pressure as a measure of energy density.

## # 2) Identifying temperature with average kinetic energy

The Ideal Gas Law, $PV = RT$ for one mole of gas, serves as a fundamental equation of state, relating the macroscopic state variables of pressure ($P$), volume ($V$), and absolute temperature ($T$).

By equating the two expressions for $PV$ derived from kinetic theory and the Ideal Gas Law (for one mole, where $N = N_A$), we establish a crucial link: $RT = \frac{2N_A}{3}\left(\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2}\right)$. Using Boltzmann's constant, $k = \frac{R}{N_A}$, which relates the ideal gas constant to Avogadro's number, this expression simplifies to the fundamental relationship between average translational kinetic energy per particle and absolute temperature: $\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2} = \frac{3}{2} kT$. This result indicates that the average speed of gas particles is $\overline{c} = \sqrt{\frac{3kT}{m}}$. Therefore, temperature is directly proportional to the average translational kinetic energy of the gas particles.

## # 3) Equipartition and degrees of freedom: “½ kT per way to move”

The equipartition theorem states that, at thermal equilibrium, each quadratic degree of freedom of a system contributes an average energy of $\frac{1}{2} kT$. A degree of freedom refers to an independent way a particle can store energy, typically associated with translational, rotational, or vibrational motion. For a monatomic ideal gas, there are three translational degrees of freedom (motion along $x$, $y$, and $z$ axes), leading to a total average translational energy of $3 \times \frac{1}{2} kT = \frac{3}{2} kT$. Diatomic molecules, being more complex, can also exhibit rotational motion (typically two quadratic degrees of freedom for a linear molecule) and, at higher temperatures, vibrational modes (each contributing two quadratic degrees of freedom, one for kinetic and one for potential energy). The contribution of these additional modes to the total energy depends on temperature, as higher temperatures "unlock" modes whose energy spacings become thermally accessible.

## # 4) Building the thermodynamics vocabulary and the Zeroth Law

To precisely describe thermodynamic interactions, a set of defined terms is necessary. A **system** is the specific part of the universe under study, such as a cup of hot tea. The **surroundings** encompass everything else interacting with the system in its immediate vicinity. The **universe** in a thermodynamic context is the combination of the system and its surroundings. Systems can be classified by their interactions: an **open system** exchanges both matter and energy with its surroundings (e.g., an open teacup); a **closed system** exchanges energy but not matter (e.g., a stoppered bottle); and an **isolated system** exchanges neither matter nor energy (e.g., an ideal thermos flask).

The concept of equilibrium can be understood through analogies. In **mechanical equilibrium**, two pressurised vessels connected by a movable piston will not experience net movement if their pressures are equal, illustrating a transitive property.

This analogy extends to **thermal equilibrium**. If two systems are in thermal contact via **diathermic walls** (which permit heat flow) and no net energy flows between them, they are in thermal equilibrium, implying they have the same "temperature." Conversely, **adiabatic walls** prevent heat flow, effectively isolating a system.

The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics formalises the concept of temperature and underpins all thermometry:

> **Zeroth law: If two systems are in each in thermal equilibrium with a third system then they are also in thermal equilibrium with each other.**

This law enables the consistent measurement of temperature across different materials and systems by ensuring that a thermometer (the third system) can accurately compare the temperatures of any two other systems placed in thermal contact with it.

## # 5) Temperature scales and absolute temperature (Kelvin)

Historical temperature scales, such as Celsius (originally defined with water boiling at $0^\circ\text{C}$ and freezing at $100^\circ\text{C}$) and Fahrenheit (based on human body temperature and a reproducible cold mixture), were initially arbitrary.

However, for fundamental thermodynamic analysis, an **absolute thermodynamic temperature** scale is required, where $T=0\,\text{K}$ represents absolute zero, the lowest possible temperature. The **Kelvin (K)** scale is the standard SI absolute scale, sharing the same step size as Celsius but shifted such that $0^\circ\text{C}$ corresponds to $273.15\,\text{K}$. The Rankine scale is the Fahrenheit-based equivalent absolute scale.

An absolute scale is measured using a **constant-volume gas thermometer**. In this device, the pressure ($P$) of an ideal gas at a fixed volume ($V$) is directly proportional to its absolute temperature ($T$). Calibration relies on a single, highly reproducible reference point: the **triple point of water**, where solid, liquid, and gas phases coexist in equilibrium, defined as $273.16\,\text{K}$ ($0.01^\circ\text{C}$). Unlike freezing or boiling points, which vary with pressure, the triple point is unique. By measuring pressure at the triple point and other temperatures, a linear $P$-$T$ plot can be generated. Extrapolating this linear relationship to $P \rightarrow 0$ identifies absolute zero, $T \rightarrow 0\,\text{K}$, where particle motion and thus pressure theoretically vanish. In 2018, the SI definition of the Kelvin was revised, directly linking temperature to energy by fixing the numerical value of Boltzmann's constant $k$.

## # 6) Microscopic temperature: Boltzmann factor and distributions

Beyond average kinetic energy, a deeper microscopic understanding of temperature involves the distribution of particle speeds and energies. The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution describes the spread of speeds and velocities among gas particles at a given temperature, with the shape of this distribution changing with temperature and particle mass.

The core concept that governs these distributions is the **Boltzmann factor**, $e^{-\beta E}$, where $\beta = \frac{1}{kT}$. This factor represents the probability weight for a particle or system to occupy an energy state $E$ at a given temperature $T$. An analogy of "balls on shelves" illustrates this: the shelves represent quantised energy levels, and the balls represent particles. At lower temperatures, most particles occupy lower energy levels (bottom shelves). As temperature increases, the population spreads across higher energy levels, reflecting the increased thermal energy.

As $T \rightarrow \infty$ (meaning $\beta \rightarrow 0$), the Boltzmann factor approaches $1$, indicating that all energy levels become equally populated. This microscopic view of temperature, describing how energy is distributed among available states, forms the basis for understanding more advanced thermodynamic concepts, such as population inversion, which refers to a non-equilibrium state where higher energy levels are more populated than lower ones.

## # 7) Bridge back to the demo and forward to next topics

The elastocaloric effect, observed with the elastic band, directly illustrates that doing work on a system can increase its internal energy and temperature, while rapid contraction can cause cooling. These phenomena are explained more fully by concepts of heat, work, and internal energy, which are central to the First Law of Thermodynamics. Future lectures will delve into the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics, providing a comprehensive energy-accounting picture that will allow a more complete understanding of the elastic band demonstration.

## Key takeaways

- **Kinetic theory to temperature:** Pressure arises from molecular momentum transfer, yielding $PV = \frac{2N}{3}\left(\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2}\right)$. This equates to $\frac{1}{2} m \overline{c^2} = \frac{3}{2} kT$, indicating that temperature is directly proportional to the average translational kinetic energy per particle, with an average speed of $\overline{c} = \sqrt{\frac{3kT}{m}}$. The equipartition theorem states that each quadratic degree of freedom contributes an average energy of $\frac{1}{2} kT$; monatomic gases, with three translational degrees of freedom, thus have $\frac{3}{2} kT$ of translational energy.

- **Thermodynamics language:** Key terms include system, surroundings, and universe, which combine to describe the scope of study. Systems are classified as open (exchanging matter and energy), closed (exchanging energy only), or isolated (exchanging neither). Walls can be diathermic (permitting heat flow) or adiabatic (preventing heat flow). The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics, which states that if two systems are each in thermal equilibrium with a third, they are in thermal equilibrium with each other, underpins the concept of temperature and the operation of thermometers.

- **Absolute temperature:** The Kelvin scale is an absolute temperature scale with $T = 0\,\text{K}$ as absolute zero. It is established via constant-volume gas thermometry, using the triple point of water ($273.16\,\text{K}$) as a reproducible reference point and extrapolating pressure to zero to find absolute zero. The modern SI definition of the Kelvin fixes Boltzmann's constant, directly linking temperature to energy.

- **Microscopic view:** Maxwell-Boltzmann distributions describe the spread of particle speeds. The Boltzmann factor, $e^{-\beta E}$ with $\beta = \frac{1}{kT}$, is a fundamental weight that quantifies how temperature influences the occupancy of different energy states.