Lecture 4: Thermal Energy of Atoms and Molecules (part 1)

0) Orientation, admin, and quick recap

A problems class has been announced for Friday, and the corresponding problem sheet is available on Blackboard. Approximately half of the problems can be solved using material from previous lectures, with the remainder becoming accessible after this week's lectures. This lecture aims to conclude the discussion on determining bond strength from macroscopic data before transitioning to the concept of thermal energy and temperature, particularly within gases. The interatomic potential well is characterised by the equilibrium separation, $a_0$, which represents the distance where attractive and repulsive forces balance, corresponding to the minimum of the potential energy. The separation energy, $\varepsilon$, signifies the depth of this well, representing the energy required to completely separate two bonded atoms. Repulsive forces at short ranges are steep and strong, primarily due to the Pauli exclusion principle, which prevents electron wavefunctions from overlapping. The attractive forces previously discussed were van der Waals forces, which arise from induced dipoles. It is crucial to remember that van der Waals bonds are significantly weaker, typically in the milli-electronvolt ($\text{meV}$) range, compared to the stronger ionic, covalent, and metallic bonds, which are on the electronvolt ($\text{eV}$) scale.

1) From latent heat to microscopic $\varepsilon$: nearest neighbours and double counting

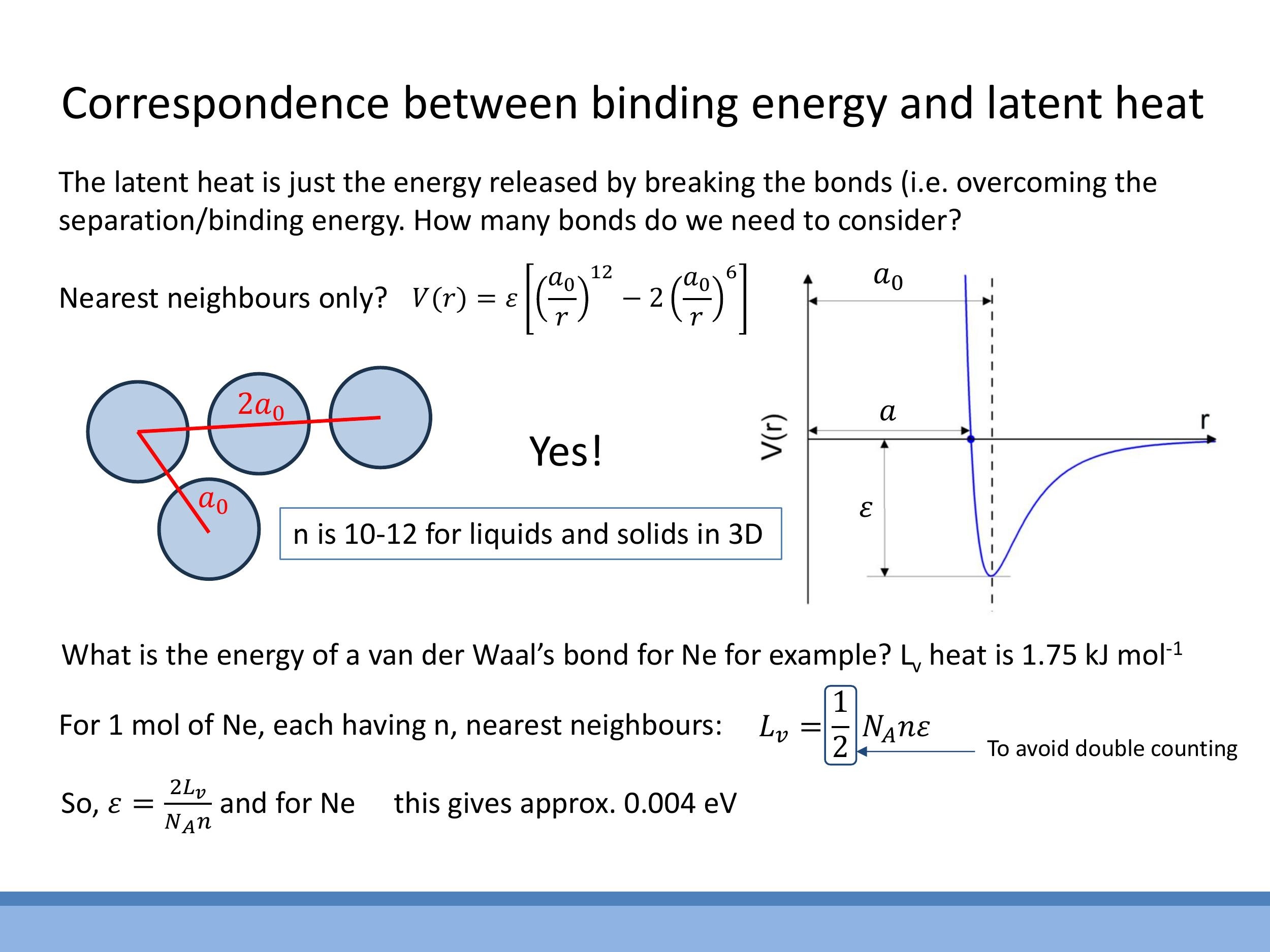

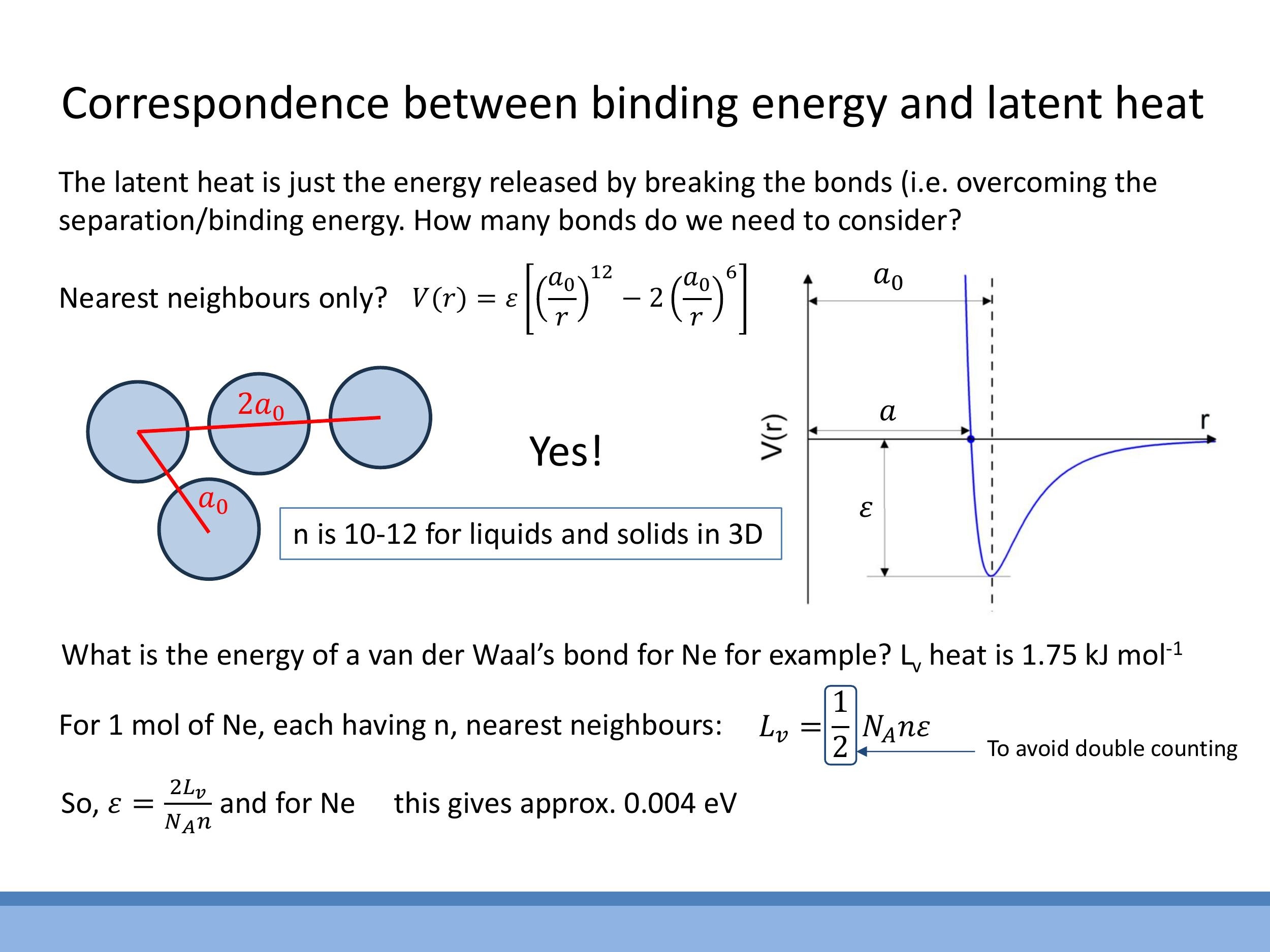

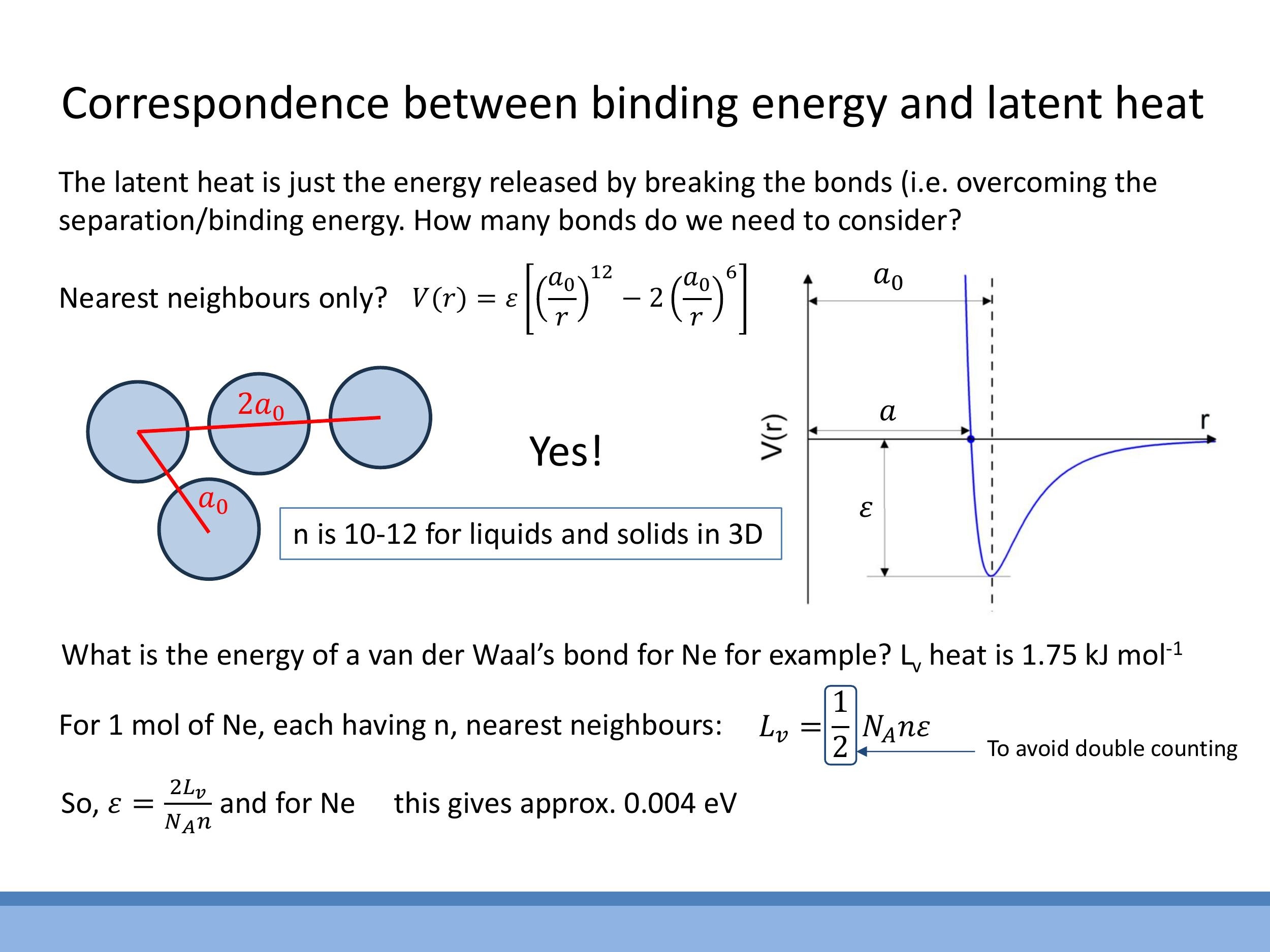

For systems bonded by van der Waals forces, interactions with nearest neighbours are predominantly responsible for the material's cohesive energy, as the van der Waals potential, $V(r)$, decays rapidly with distance, proportional to $r^{-6}$. The latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, represents the energy required to break all intermolecular bonds in one mole of a substance. To relate this macroscopic quantity to the microscopic separation energy, $\varepsilon$, the number of nearest neighbours, $n$, must be considered. In liquids, the average number of nearest neighbours is approximately $n \approx 10$. In close-packed solids, this number is typically $n = 12$. Each intermolecular bond is shared between two atoms, necessitating a factor of $\frac{1}{2}$ to avoid double-counting when summing the total bond energy per mole. This leads to the relationship:

$$

L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon

$$

Rearranging this expression allows for the calculation of the microscopic separation energy: $\varepsilon = \frac{2 L_v}{N_A n}$. For example, using Neon with a latent heat of vaporisation $L_v = 1.75 \, \text{kJ mol}^{-1} $ and an average of $ n \approx 10 $ nearest neighbours (as it is liquid at its boiling point), the calculated separation energy $ \varepsilon $ is approximately $ 0.004 \, \text{eV}$. This value quantitatively demonstrates that van der Waals bonds are thousands of times weaker than typical strong bonds, which are on the electronvolt scale.

⚠️ Exam Alert! The lecturer explicitly stated: "And this is not so different for a typical multiple choice question that you could get in the December multiple choice exam." This type of calculation, involving the relationship between latent heat and microscopic bond energy, is directly examinable. Students should be proficient in performing such calculations and understanding the physical implications of the result.

2) Three strong bond types: quick orientation

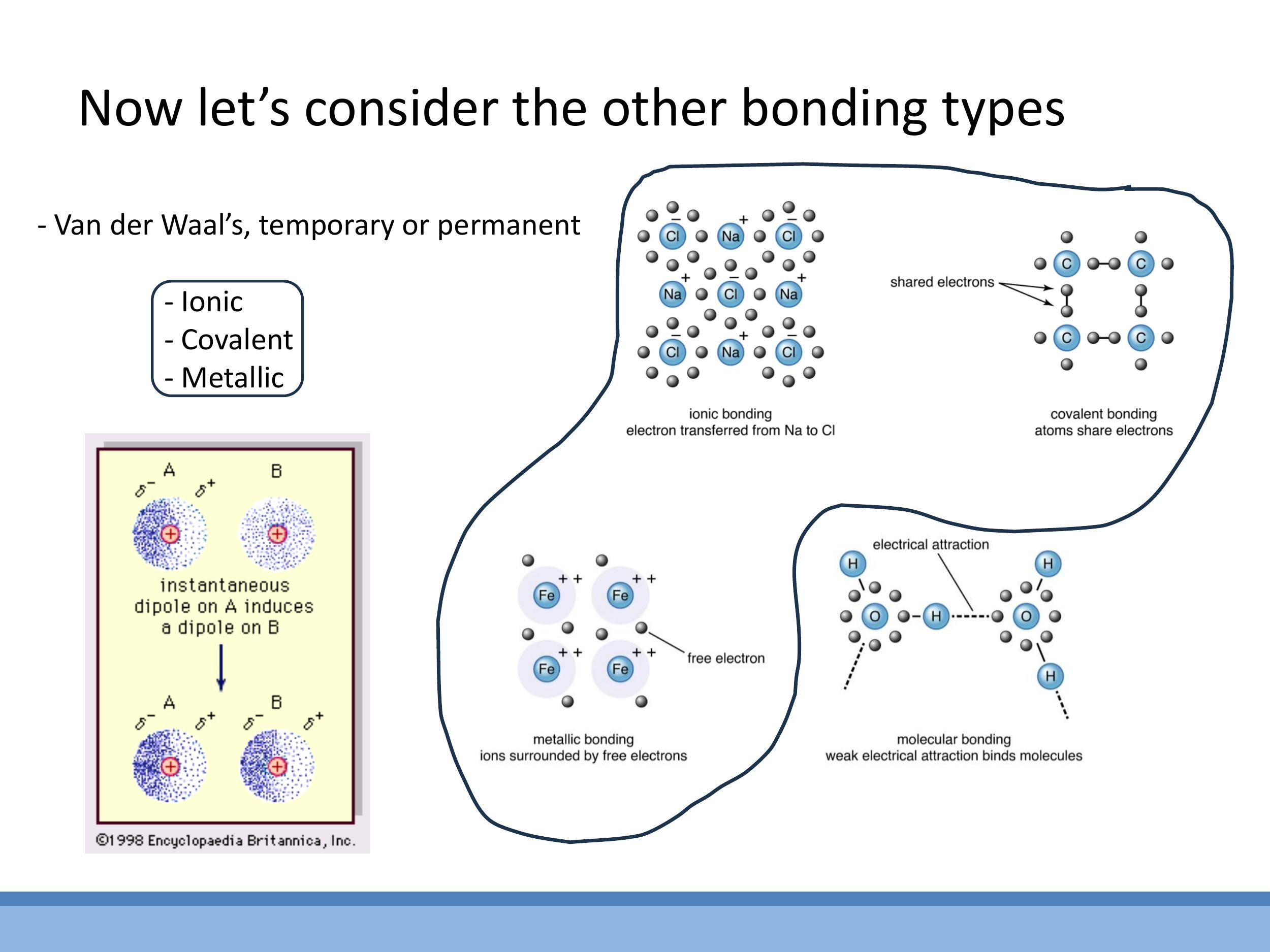

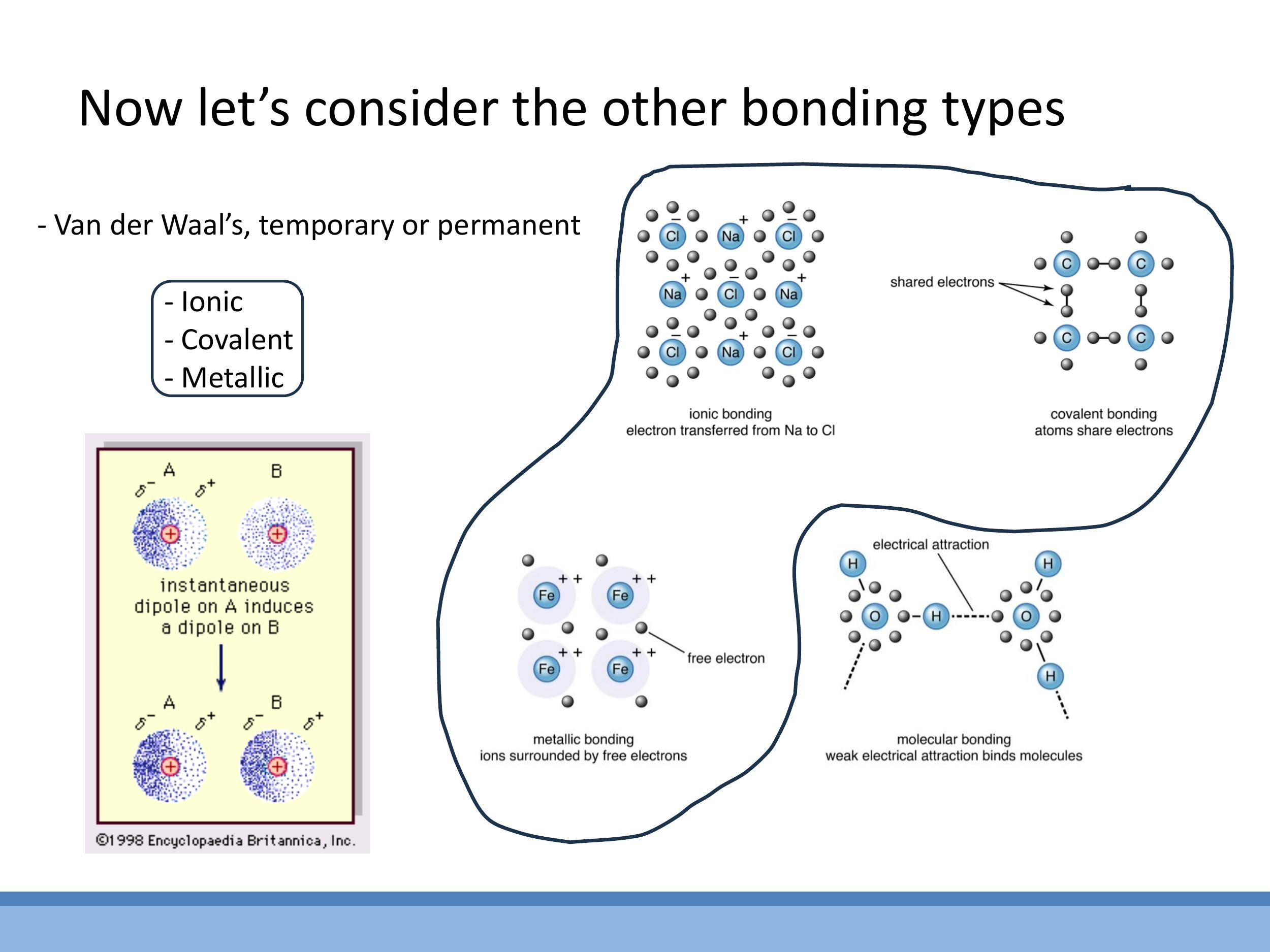

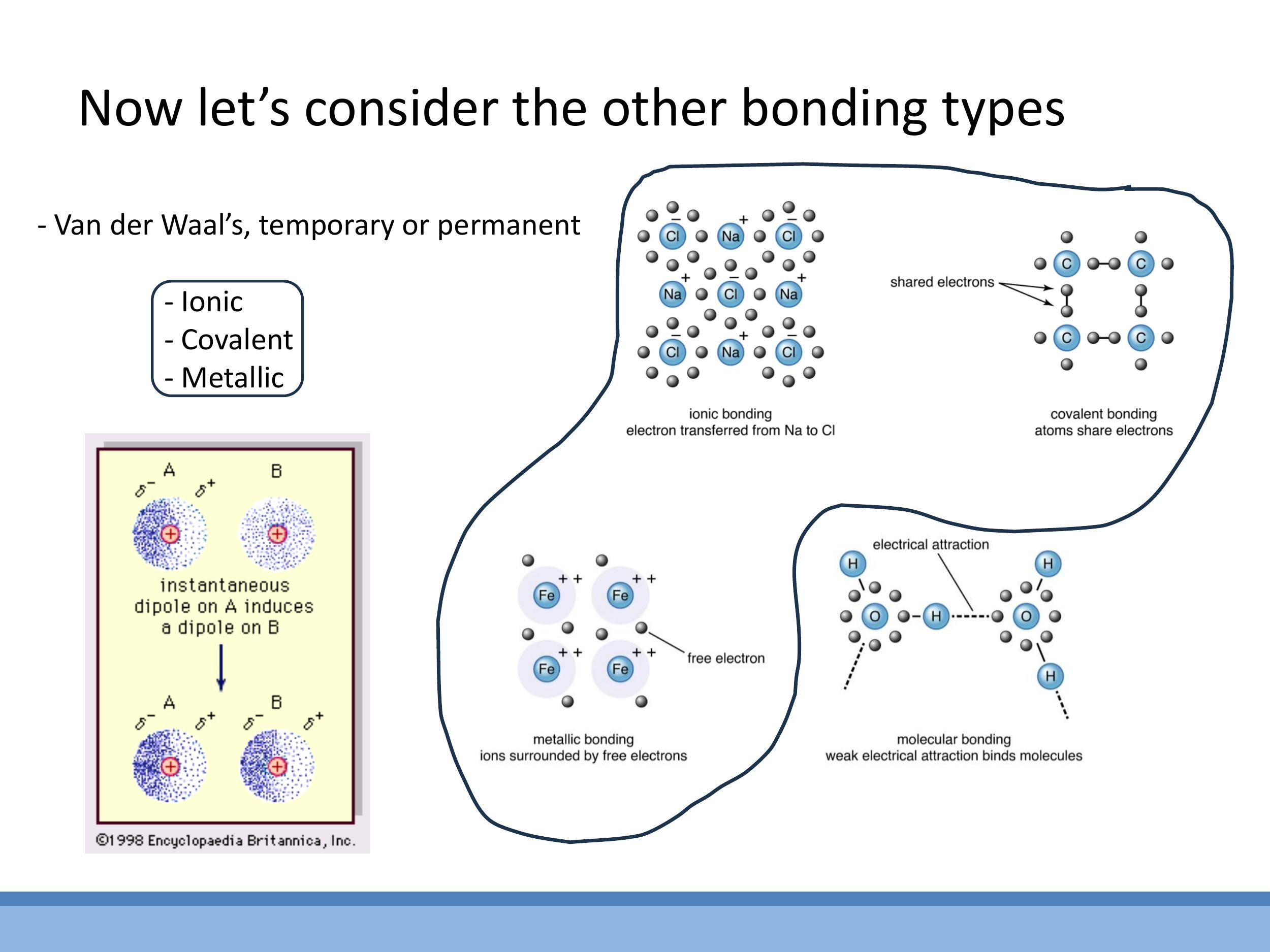

In addition to the weak van der Waals forces, three primary types of strong interatomic bonds exist, all characterised by bond strengths on the order of several electronvolts ($\text{eV}$). Ionic bonding arises from the complete transfer of electrons between atoms, creating oppositely charged ions (cations and anions) that are held together by strong Coulomb attraction. Covalent bonding involves the sharing of electron pairs between nuclei, forming strong, directional bonds. Metallic bonding is characterised by an array of positive ion cores immersed in a "sea" of delocalised valence electrons, resulting in strong, non-directional cohesive forces. While ionic bonding will be treated quantitatively, covalent and metallic bonding will be primarily discussed conceptually with key terminology.

3) Ionic bonding: long-range Coulomb attraction and lattice sums

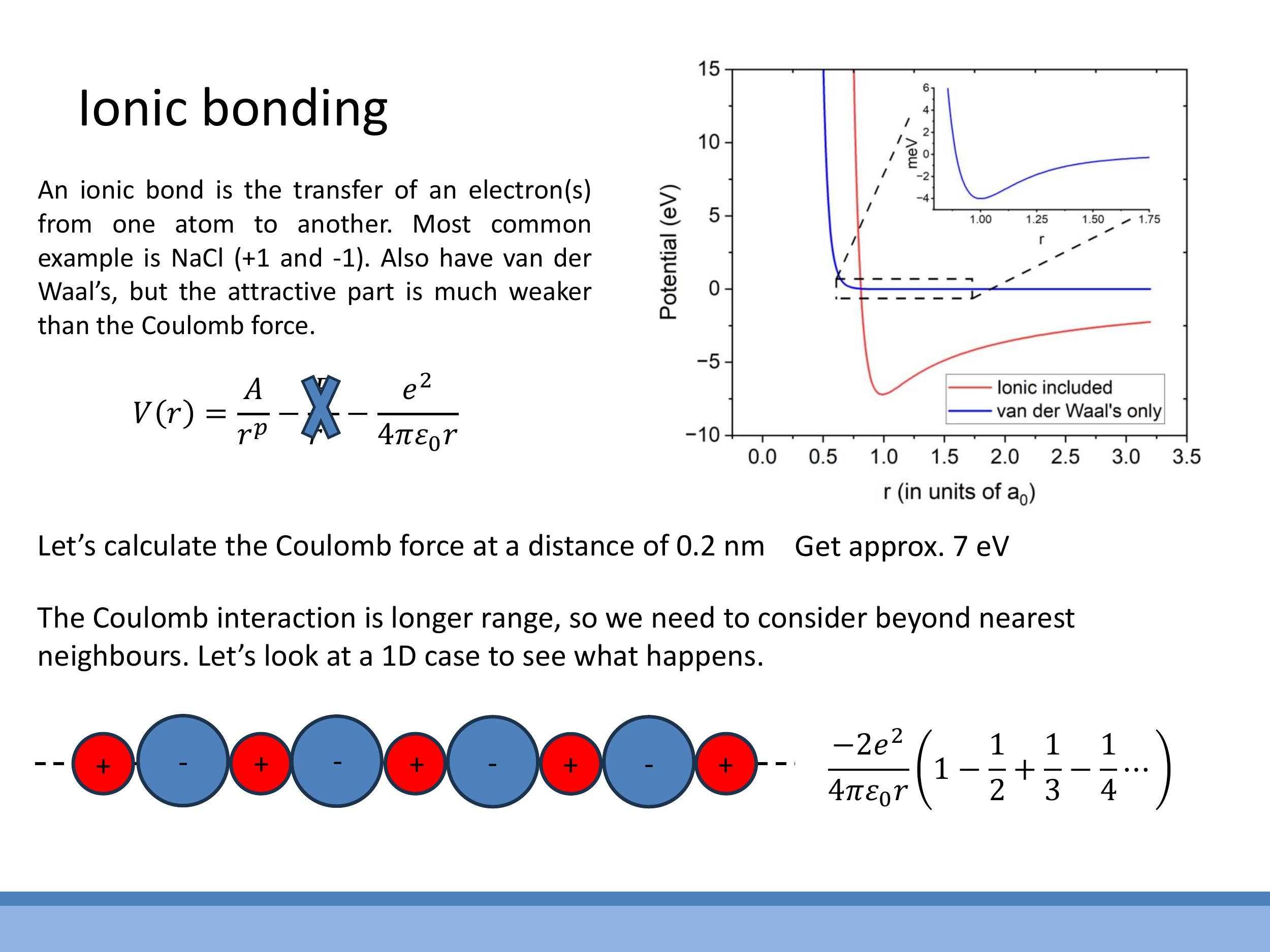

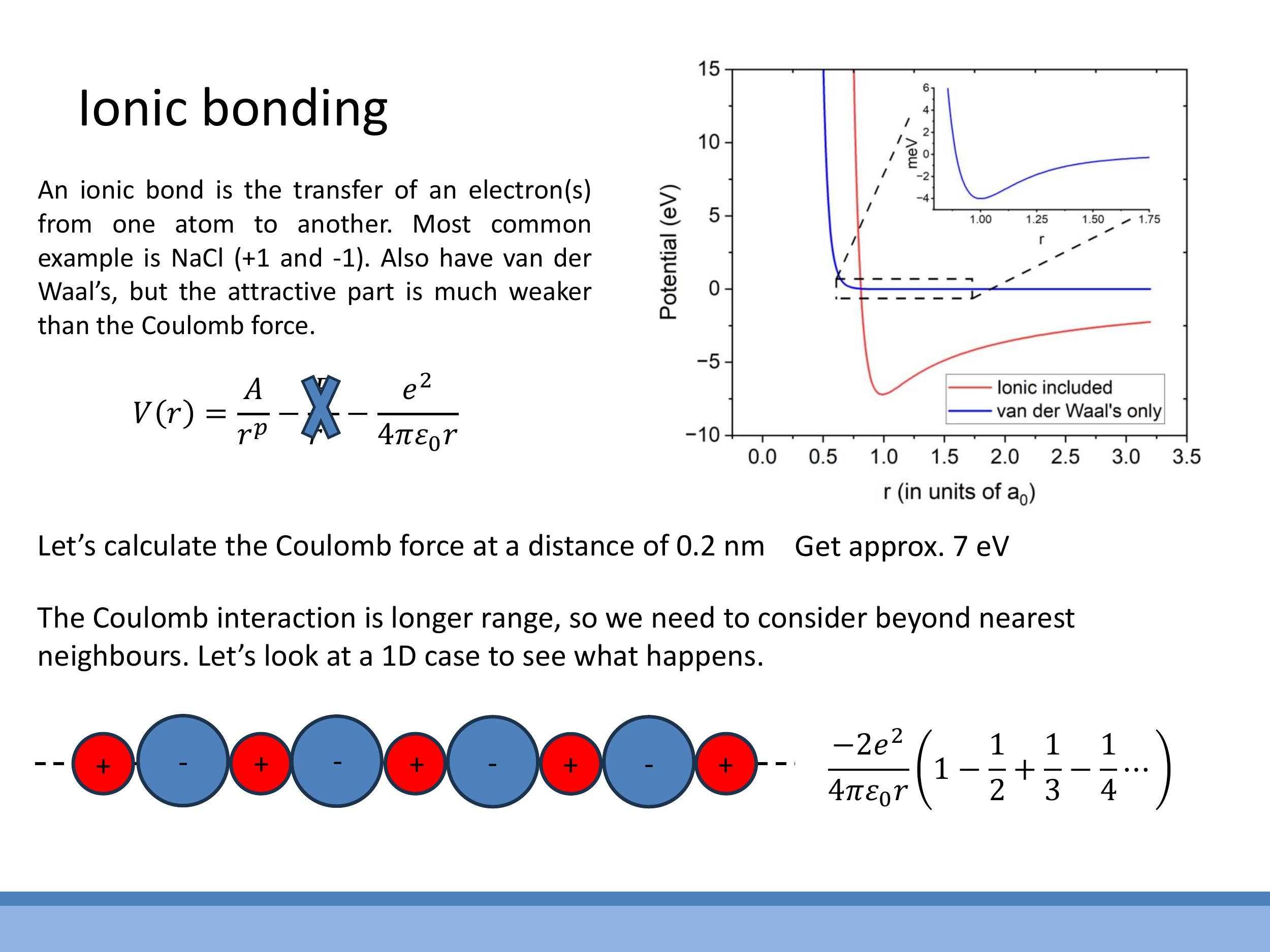

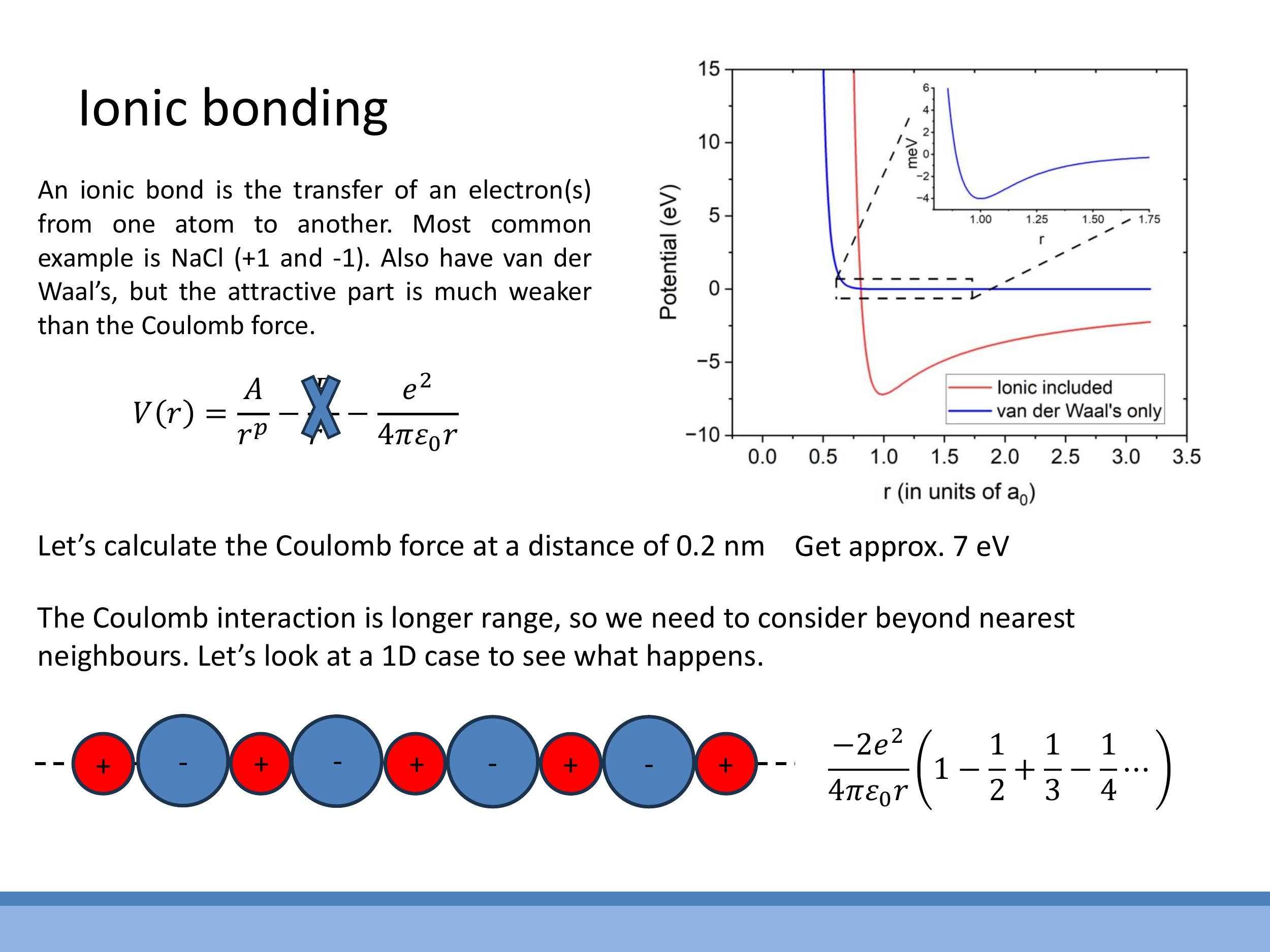

Ionic bonds differ fundamentally from van der Waals interactions due to their long-range Coulomb attraction, which decays as $1/r$. This contrasts with the rapid $1/r^6$ decay of van der Waals forces. A simple model for the potential energy, $V(r)$, between two ions in an ionic solid includes a short-range repulsive term and a long-range Coulomb attractive term:

$$

V(r) = \frac{A}{r^p} - \frac{e^2}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r}

$$

At a typical interionic separation of $r \approx 0.2 \, \text{nm} $ (or $ 2 \, \text{Å} $), the Coulomb attractive term is approximately $ 7 \, \text{eV}$, confirming the strong nature of ionic bonds.

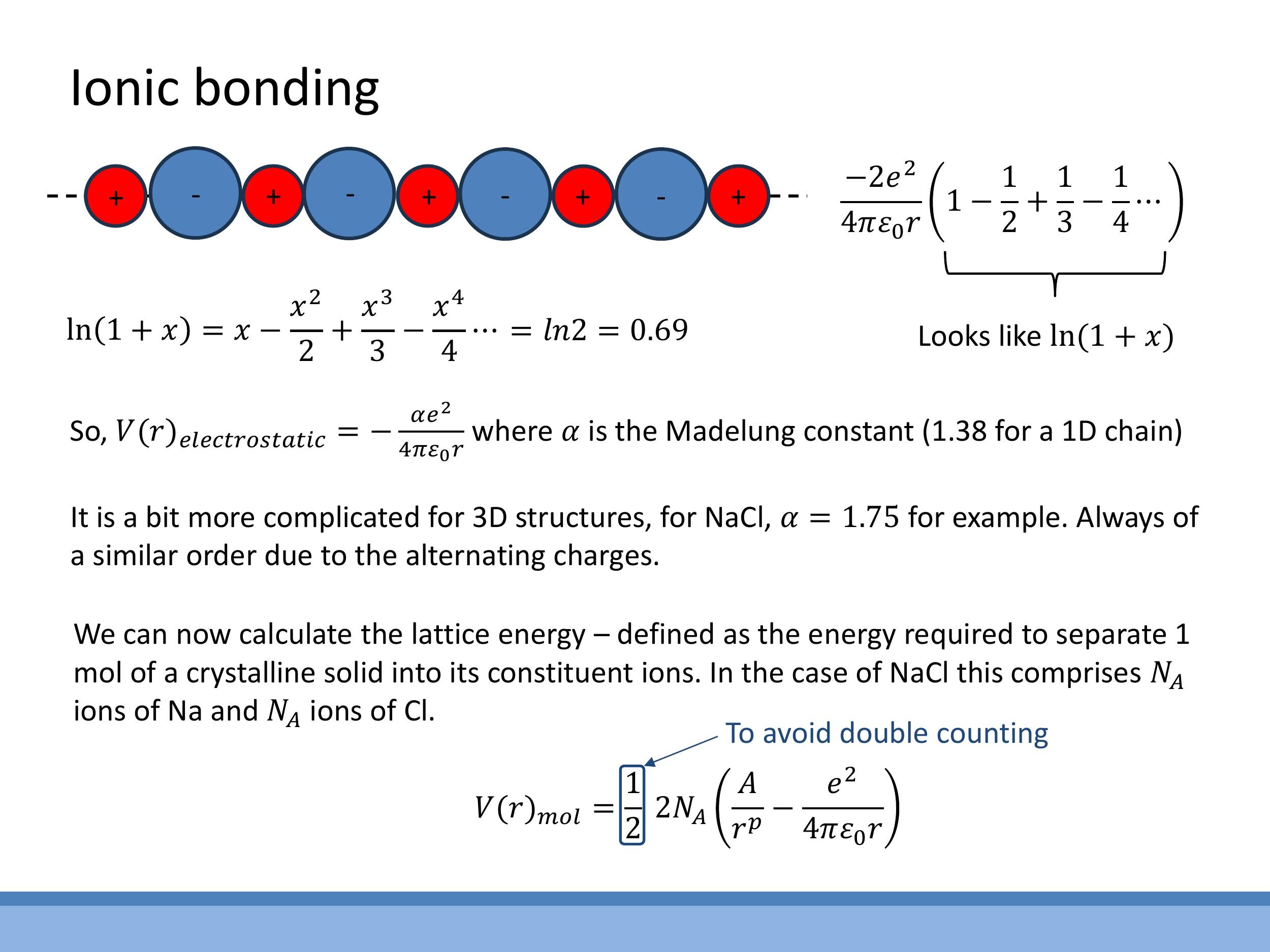

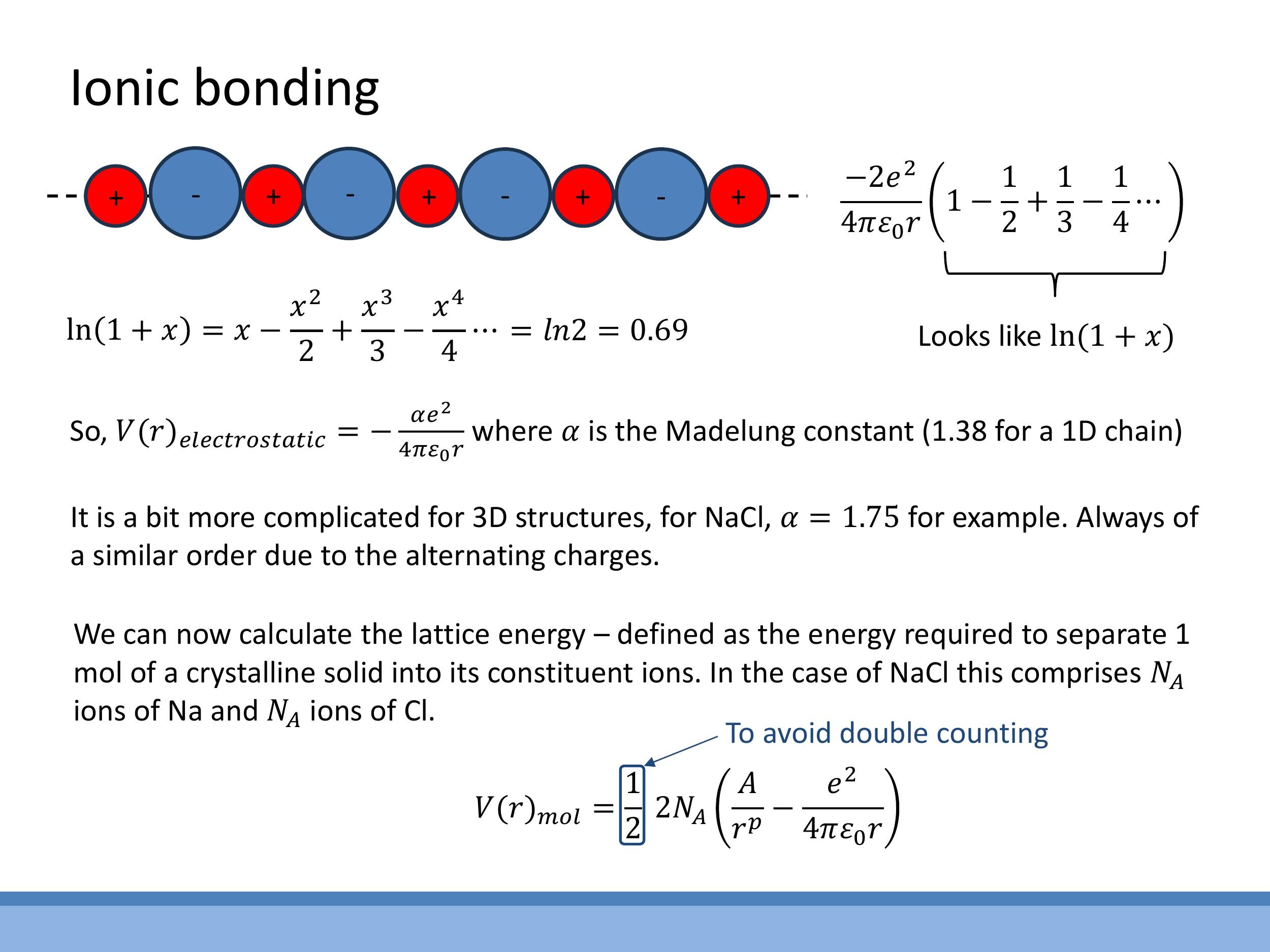

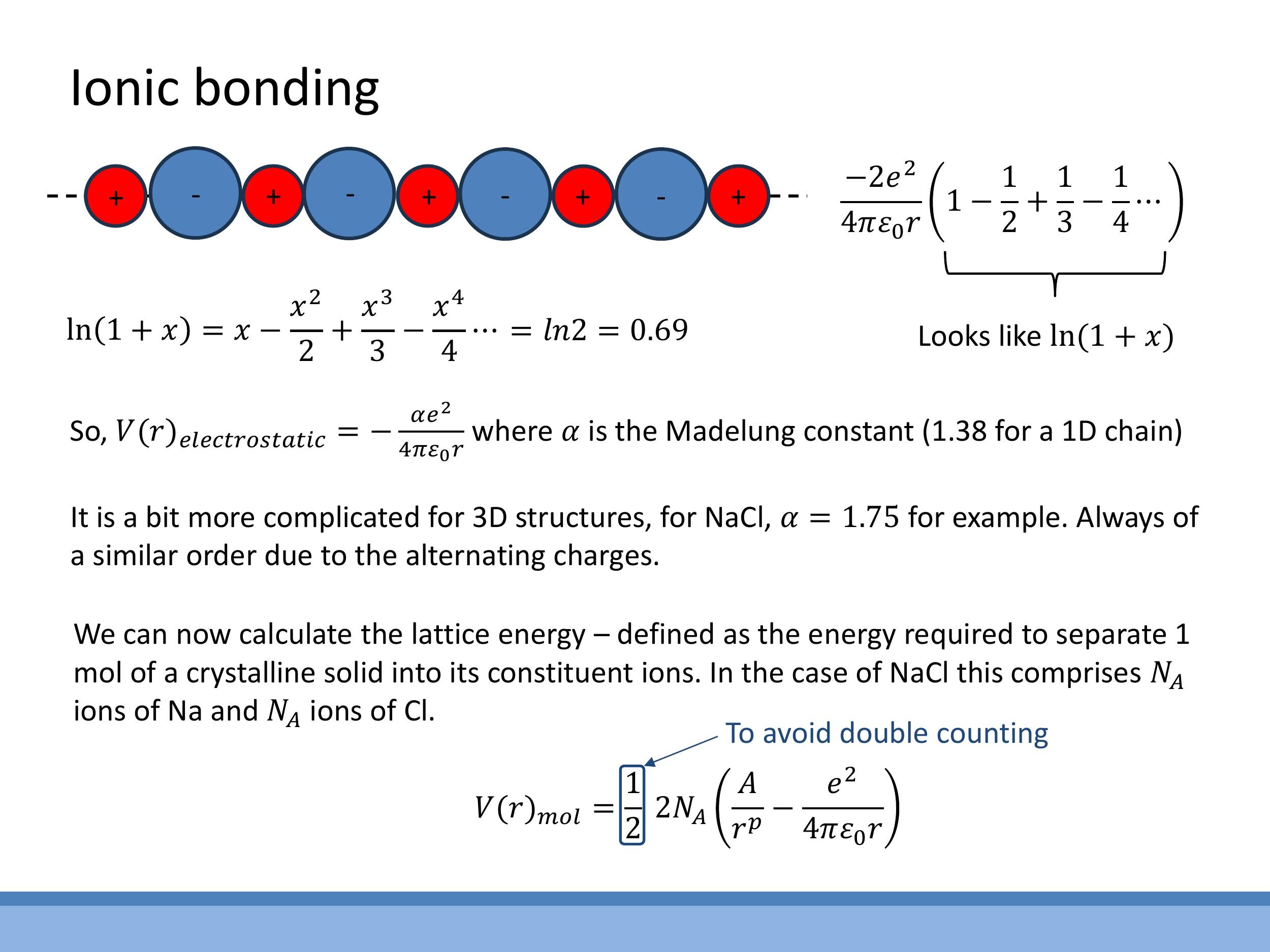

Because the Coulomb force is long-range, interactions beyond just nearest neighbours are significant and must be included in the total potential energy calculation for an ionic solid. This is illustrated by considering a one-dimensional alternating chain of positive and negative ions. The summation of these alternating attractive and repulsive interactions leads to a series of the form $1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{4} + \dots$, which converges to $\ln 2$. This geometric summation is encapsulated by the Madelung constant, $\alpha$, which accounts for the specific lattice geometry in the net electrostatic prefactor. The electrostatic potential for an ion in a lattice is thus given by:

$$

V(r)_{\text{electrostatic}} = -\frac{\alpha e^2}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r}

$$

For a one-dimensional chain, $\alpha \approx 1.38$ (derived from $2\ln 2$). For a three-dimensional sodium chloride (NaCl) lattice, $\alpha \approx 1.75$. In practical calculations, such as those in an exam, the value of $\alpha$ would typically be provided, and students would be expected to utilise it in the formula.

The lattice energy is defined as the energy required to separate one mole of a crystalline ionic solid into its gaseous constituent ions. For macroscopic crystals, the properties are dominated by the bulk, and edge corrections are negligible.

4) Covalent bonding: sharing electrons and the Morse potential

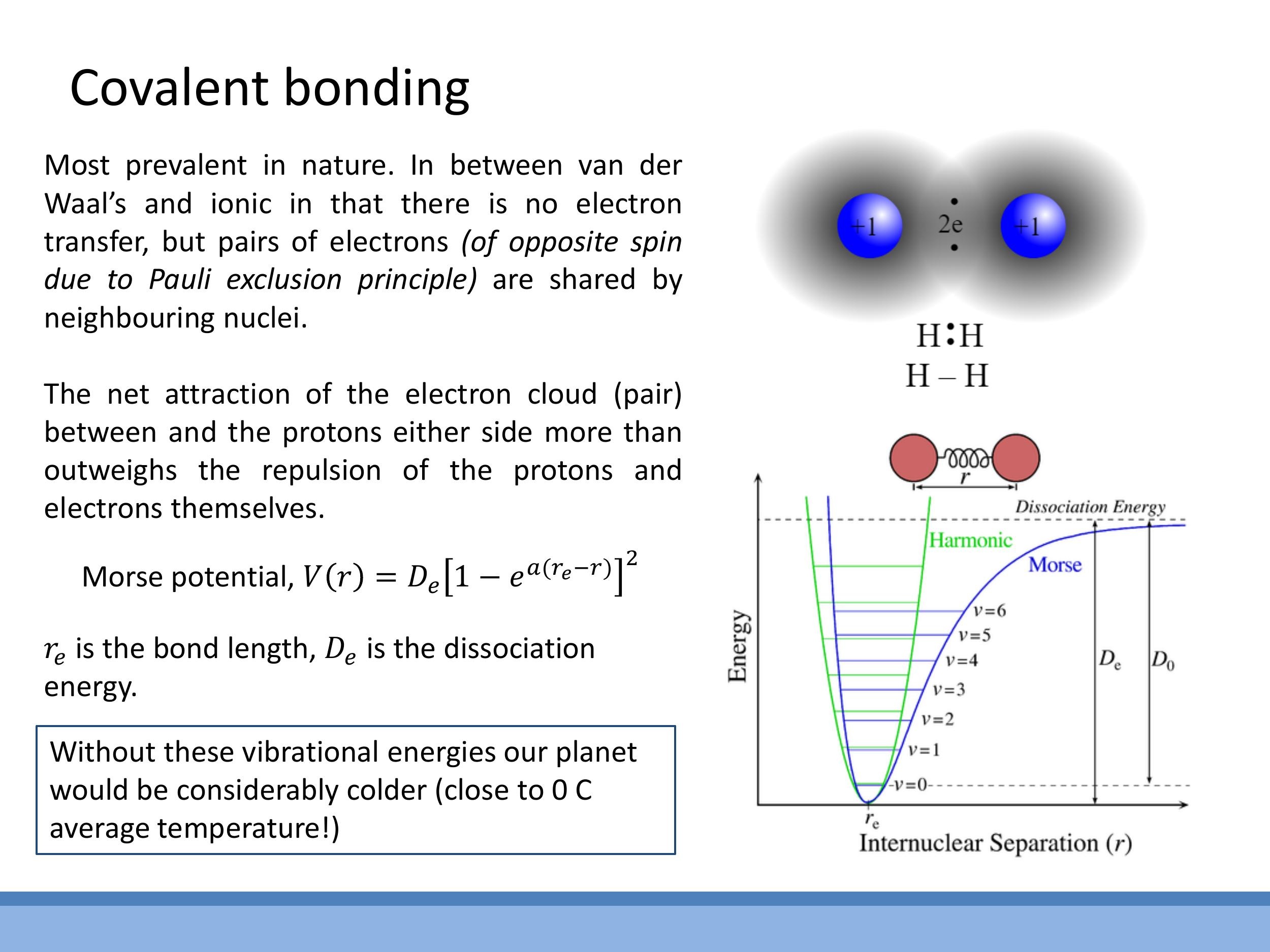

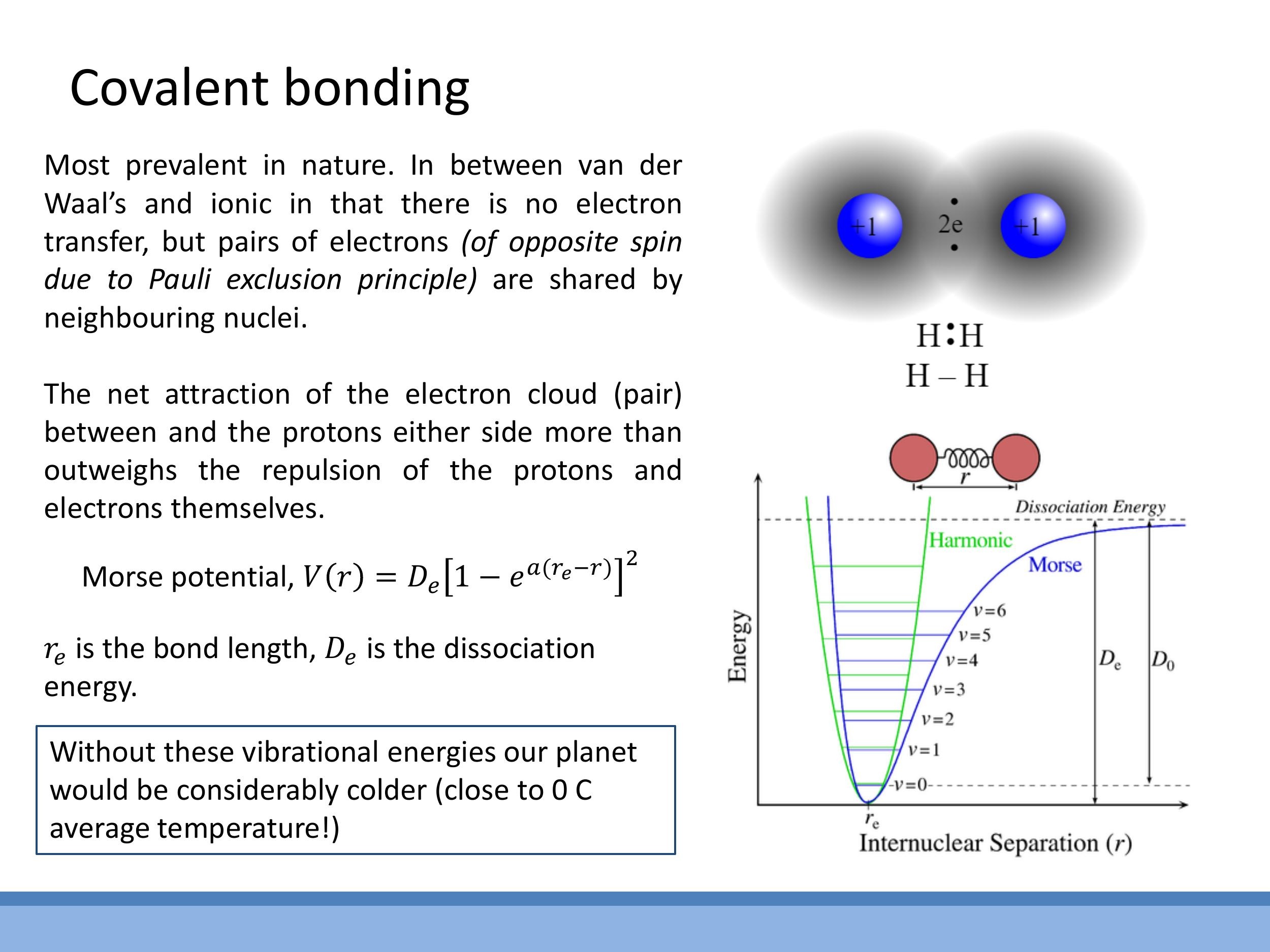

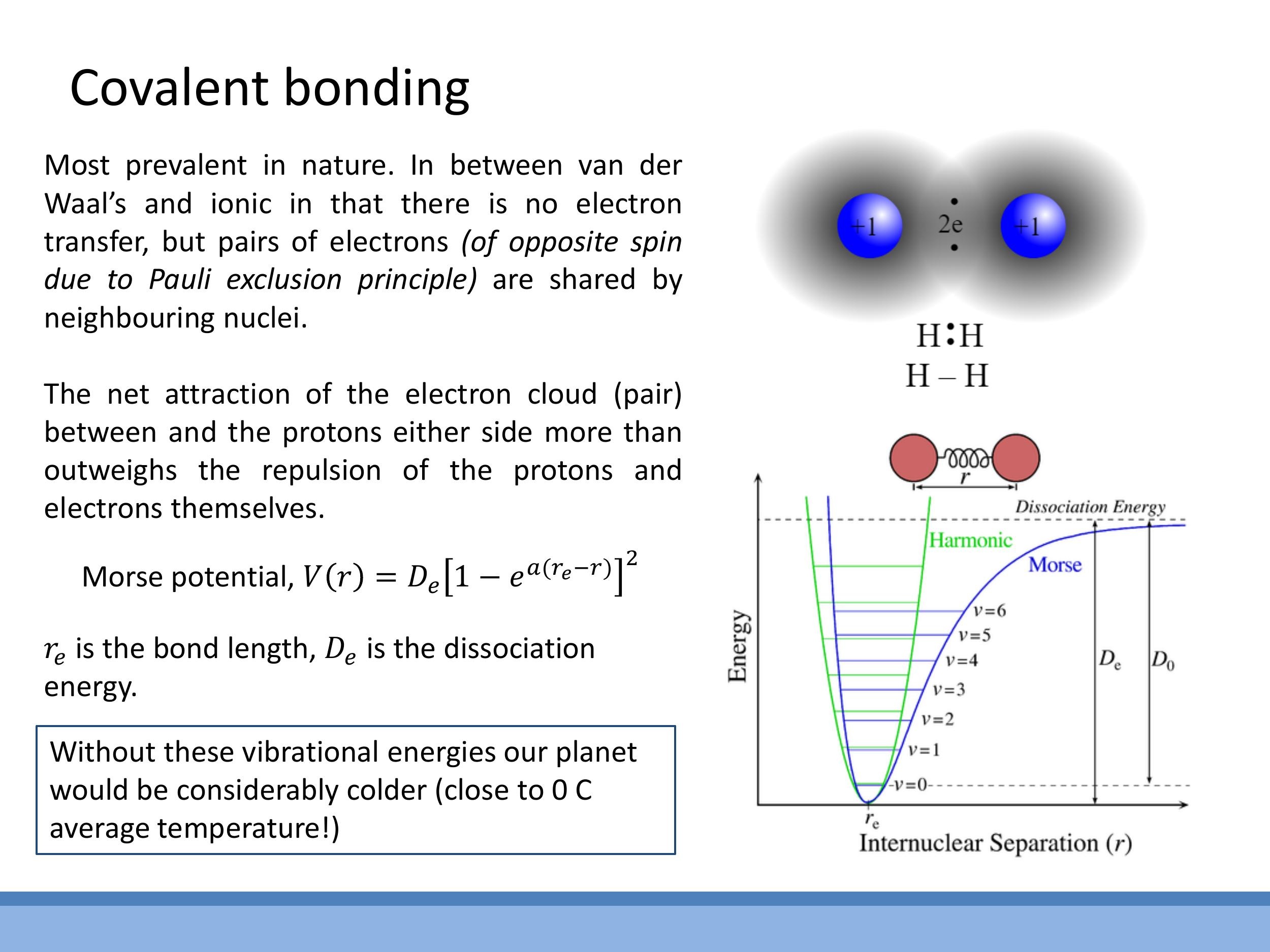

Covalent bonds are formed by the sharing of a pair of electrons, typically with opposite spins, between two adjacent nuclei. This shared electron density between the positively charged nuclei creates a strong attractive force that holds the atoms together, overcoming the internuclear repulsion. The potential energy of a covalent bond is often described by the Morse potential:

$$

V(r) = D_e \left[ 1 - e^{a(r_e - r)} \right]^2

$$

Here, $r_e$ represents the equilibrium bond length, and $D_e$ is the dissociation energy, which is equivalent to the separation energy, $\varepsilon$, discussed for other bond types. It represents the depth of the potential well and the energy required to break the bond. Within the Morse potential well, molecules can occupy quantised vibrational energy levels. The absorption of infrared radiation by atmospheric molecules, such as carbon dioxide ($\text{CO}_2$) and nitrogen ($\text{N}_2$), excites these vibrational states, playing a critical role in maintaining Earth's surface temperature.

To illustrate the strength of covalent bonds, consider the dissociation temperature for a hydrogen molecule ($\text{H}_2$). By equating the average thermal energy of a particle, $\frac{3}{2}kT$, to the dissociation energy, $D_e$, we can estimate the temperature required to break the bond. For $\text{H}_2$, $D_e \approx 4.4 \, \text{eV} $. Solving for $ T $ yields an approximate temperature of $ 3 \times 10^4 \, \text{K}$. This extremely high temperature demonstrates the immense strength of covalent bonds on thermal scales.

⚠️ Exam Alert! The lecturer explicitly stated: "This is not so different from standard typical multiple choice questions that you'll get in December." Calculations involving the dissociation temperature of covalent bonds are directly examinable.

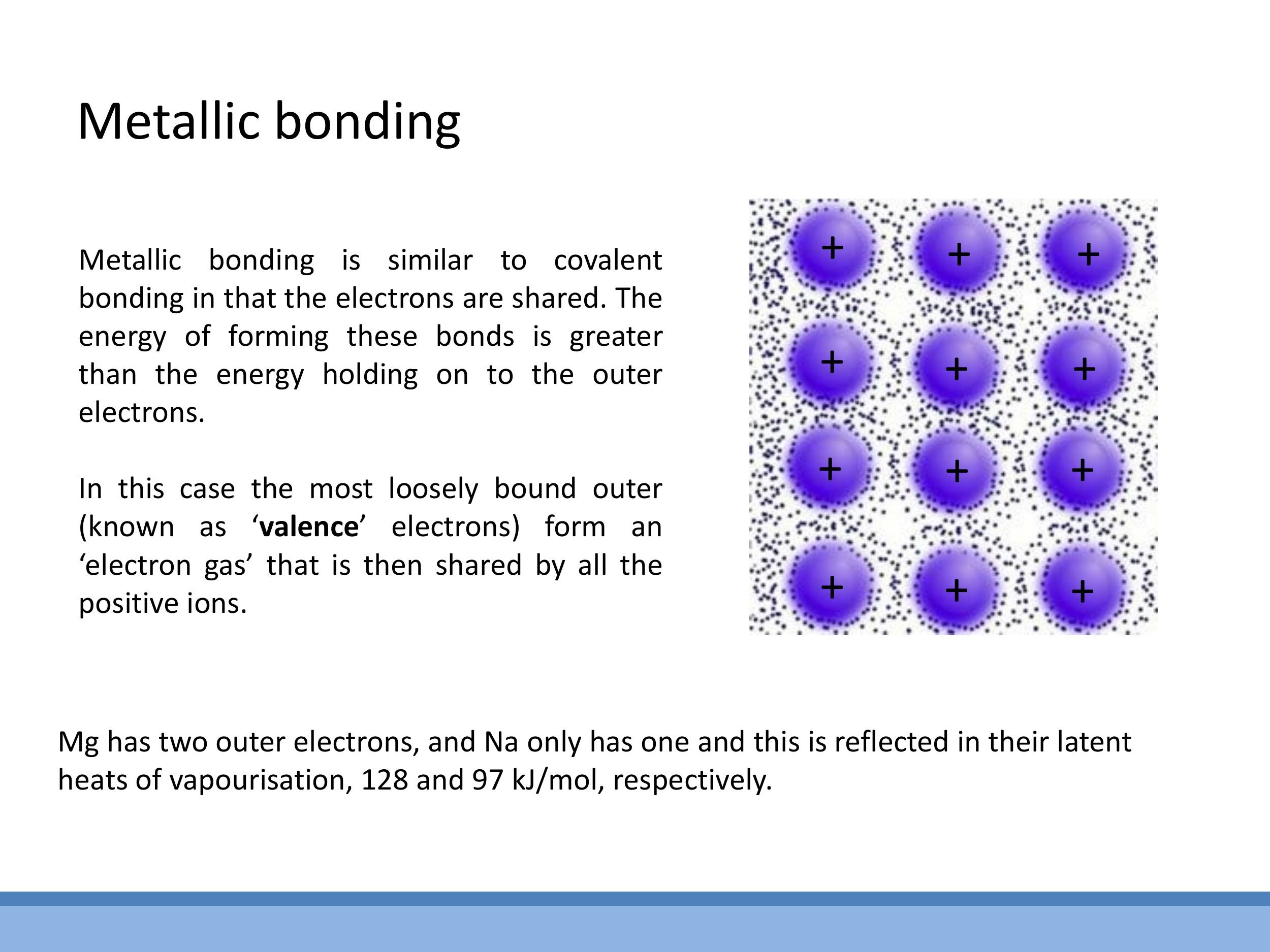

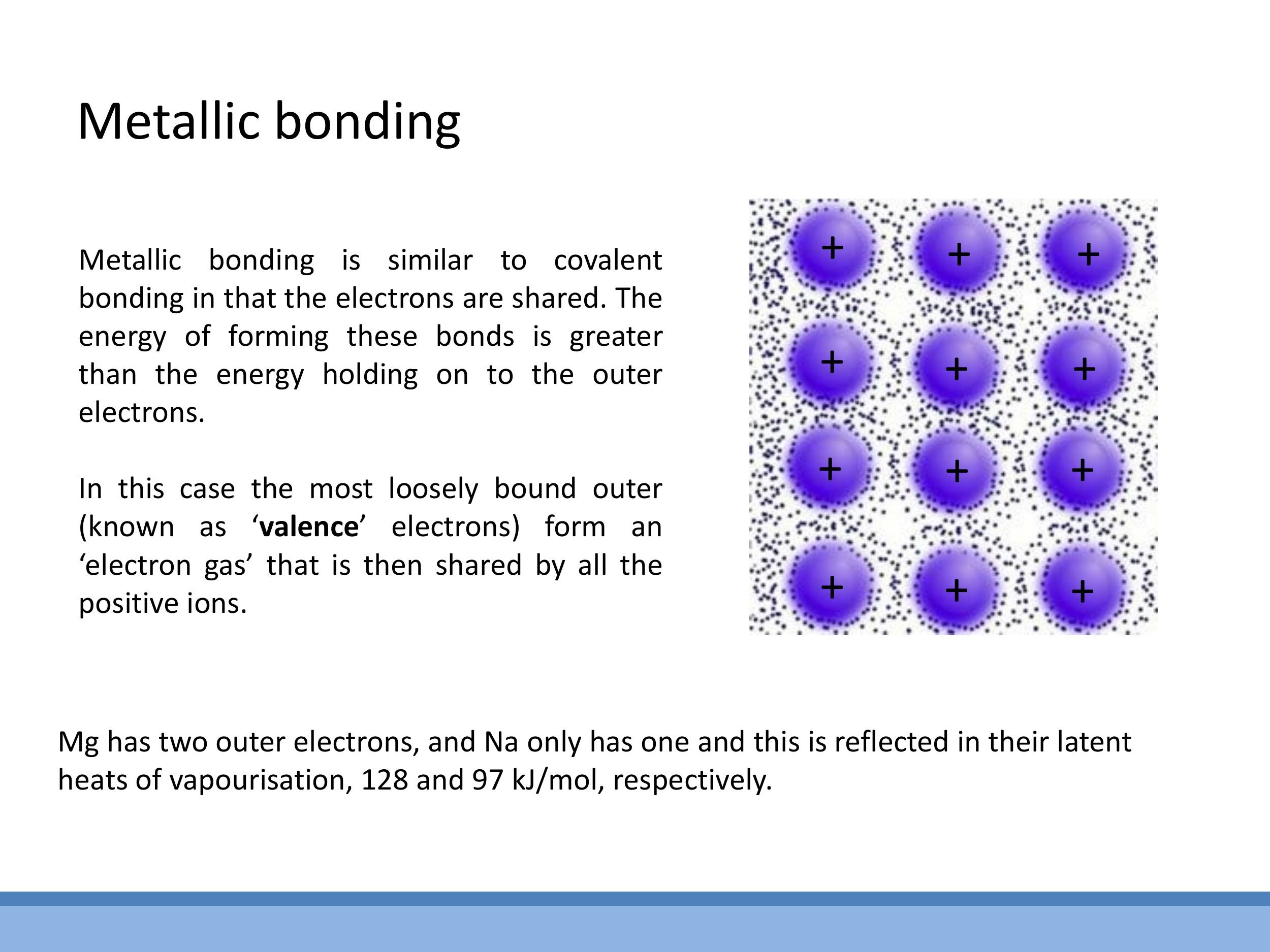

Metallic bonding is characterised by an array of positive ion cores immersed in a "sea" of delocalised valence electrons. These electrons are not bound to individual atoms but move freely throughout the metal lattice, providing strong, non-directional cohesive forces. The strength of metallic bonds is generally comparable to that of ionic and covalent bonds. The density of the electron sea influences the bond strength; for instance, magnesium ($\text{Mg}$), with two valence electrons, exhibits stronger metallic bonding than sodium ($\text{Na}$), which has only one. This difference is reflected in their respective latent heats of vaporisation: $128 \, \text{kJ mol}^{-1} $ for $ \text{Mg} $ compared to $ 97 \, \text{kJ mol}^{-1} $ for $ \text{Na}$, indicating that more energy is required to break the bonds in magnesium.

6) Thermal energy and the concept of temperature: starting kinetic theory of gases

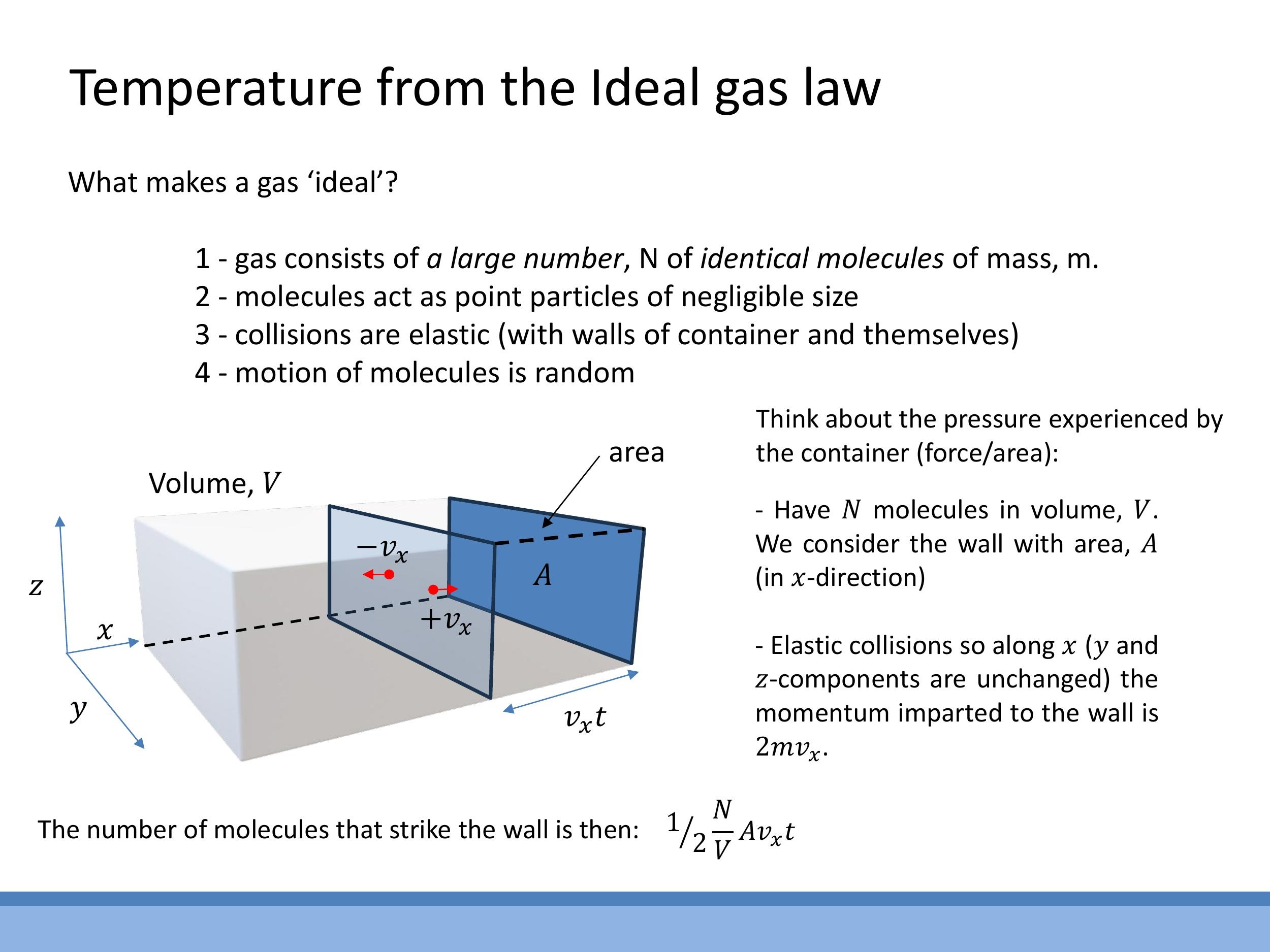

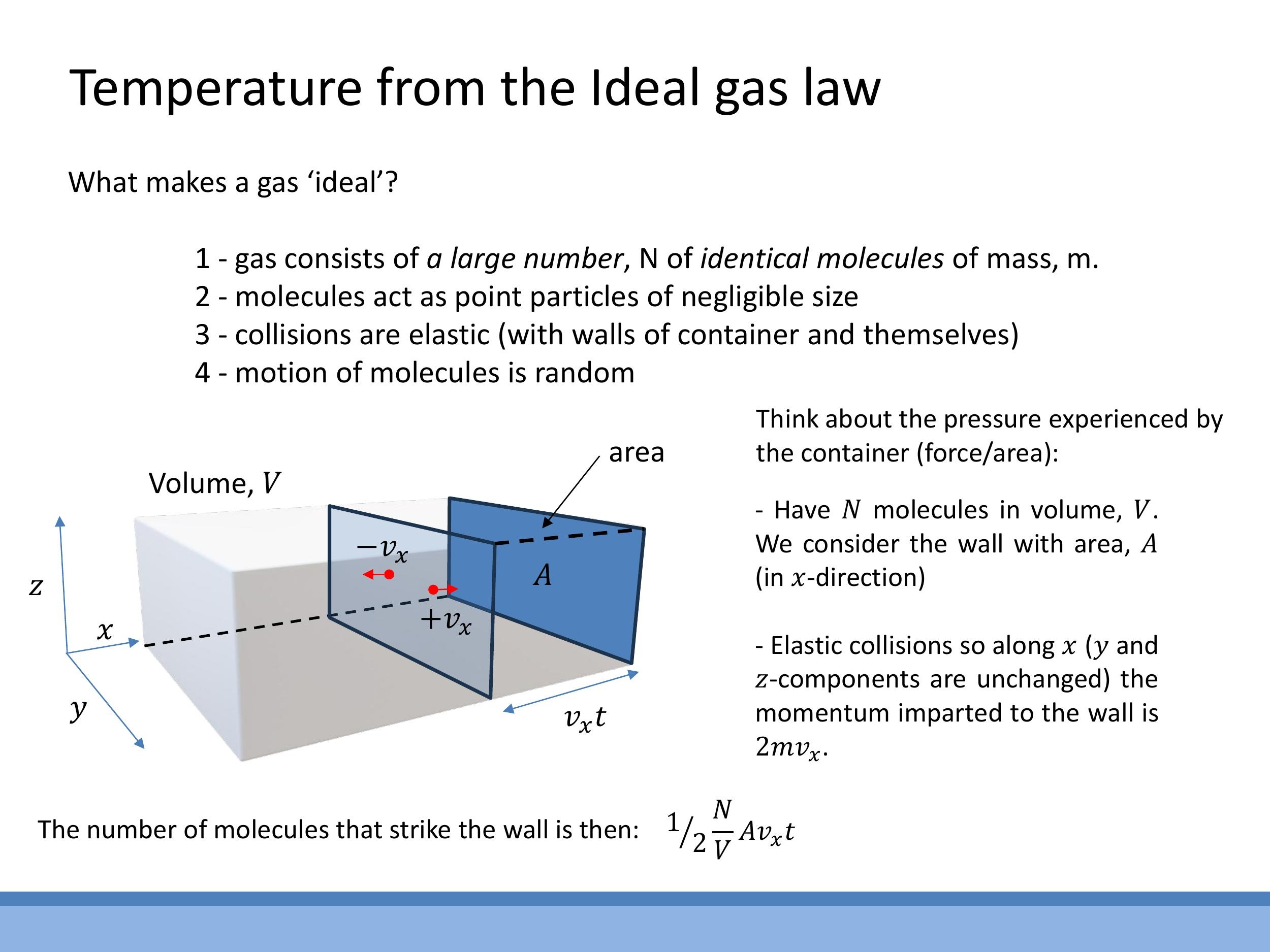

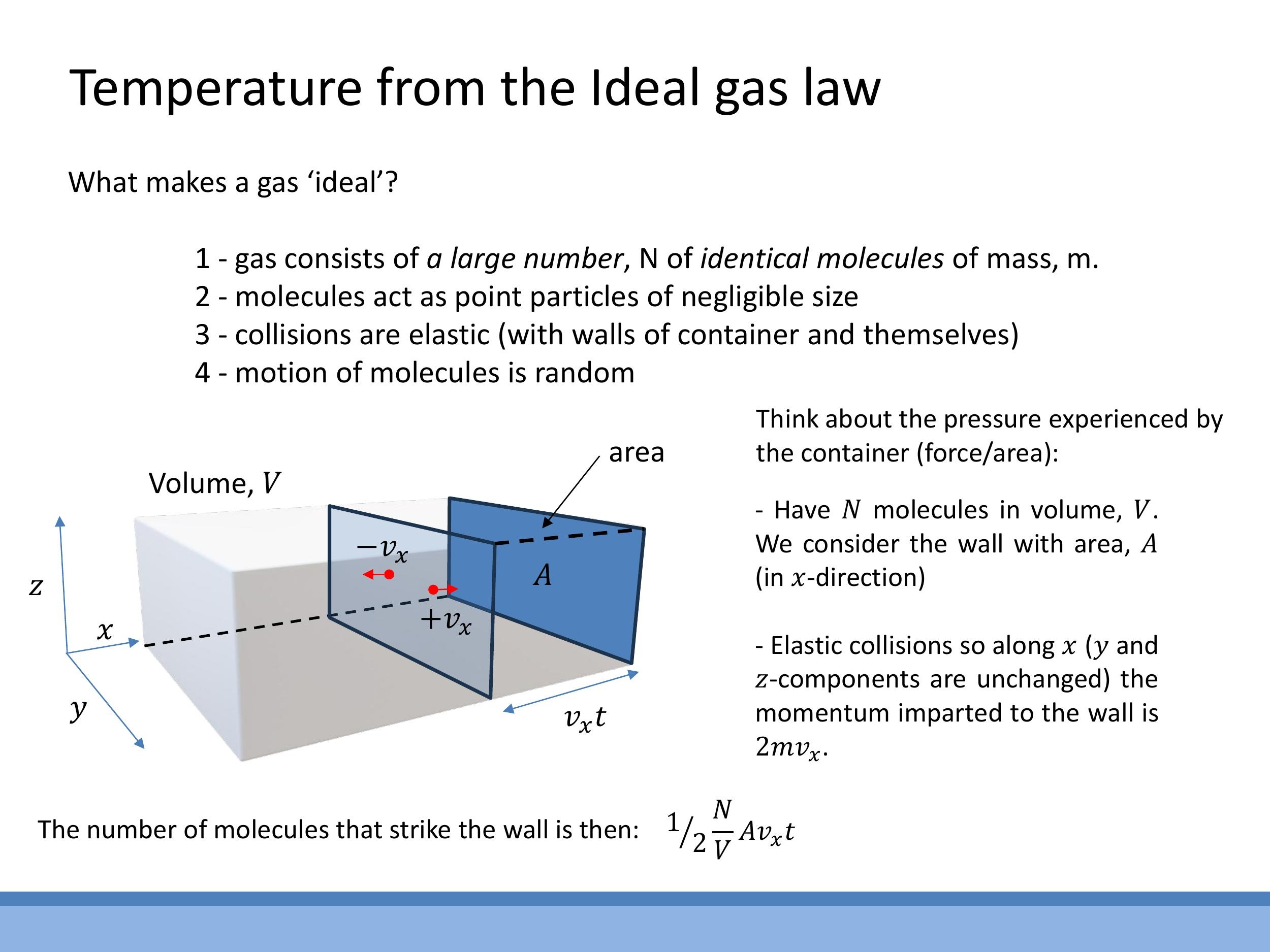

The kinetic theory of gases provides a microscopic framework for understanding the macroscopic properties of gases, including temperature and pressure. An ideal gas is defined by several key assumptions: it consists of a large number ($N$) of identical molecules, which are treated as point particles with negligible size. All collisions, both between molecules and with the container walls, are perfectly elastic, and the motion of these molecules is completely random.

Pressure in a gas arises from the cumulative effect of countless molecular impacts on the container walls. Each collision involves a transfer of momentum. For a molecule striking a wall perpendicularly and elastically, the momentum transferred to the wall is $2mv_x$, where $m$ is the mass of the molecule and $v_x$ is its velocity component perpendicular to the wall. The number of molecules striking a wall of area $A$ in a time $t$ can be estimated as $\frac{1}{2} \frac{N}{V} A v_x t$, where $\frac{N}{V}$ is the number density of the gas, and the factor of $\frac{1}{2}$ accounts for, on average, half the molecules moving towards the wall. The full derivation of pressure and its link to temperature will be completed in the next lecture.

Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

Slides detailing the Born-Landé lattice-energy derivation steps for $\text{NaCl}$ and the equilibrium condition were present in the lecture materials but were not covered in this session. Their results should not be integrated into the main narrative of this lecture.

Key takeaways

The microscopic "bond energy" is represented by $\varepsilon$, the depth of the potential well, with $a_0$ being the equilibrium spacing at the potential minimum. For materials bonded by van der Waals forces, the latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, is linked to $\varepsilon$ through the number of nearest neighbours, $n$, and a $\frac{1}{2}$ double-counting factor: $L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon$. Typical van der Waals bond strengths are in the range of $10^{-3} \text{-} 10^{-2} \, \text{eV} $. Stronger bonds, including ionic, covalent, and metallic bonds, are on the $ \text{eV} $ scale. Ionic attraction is a long-range $ 1/r $ interaction, requiring lattice sums accounted for by the Madelung constant, $ \alpha $. Covalent bonds are well-described by the Morse potential, where the dissociation energy, $ D_e $, is equivalent to $ \varepsilon $. Dissociating a hydrogen molecule ($ \text{H}_2 $) requires temperatures around $ 3 \times 10^4 \, \text{K} $, highlighting the extreme strength of covalent bonds. Metallic bonding results from a "sea" of delocalised electrons, and an increased number of valence electrons generally strengthens the bond, as seen by comparing magnesium ($ \text{Mg} $) and sodium ($ \text{Na}$). The foundations of kinetic theory involve ideal gas assumptions, where pressure originates from the momentum transfer during elastic molecular collisions. The initial steps for calculating the collision count have been established, with the complete derivation of pressure-temperature relations to follow in the next lecture.

## Lecture 4: Thermal Energy of Atoms and Molecules (part 1)

### 0) Orientation, admin, and quick recap

A problems class has been announced for Friday, and the corresponding problem sheet is available on Blackboard. Approximately half of the problems can be solved using material from previous lectures, with the remainder becoming accessible after this week's lectures. This lecture aims to conclude the discussion on determining bond strength from macroscopic data before transitioning to the concept of thermal energy and temperature, particularly within gases. The interatomic potential well is characterised by the equilibrium separation, $a_0$, which represents the distance where attractive and repulsive forces balance, corresponding to the minimum of the potential energy. The separation energy, $\varepsilon$, signifies the depth of this well, representing the energy required to completely separate two bonded atoms. Repulsive forces at short ranges are steep and strong, primarily due to the Pauli exclusion principle, which prevents electron wavefunctions from overlapping. The attractive forces previously discussed were van der Waals forces, which arise from induced dipoles. It is crucial to remember that van der Waals bonds are significantly weaker, typically in the milli-electronvolt ($\text{meV}$) range, compared to the stronger ionic, covalent, and metallic bonds, which are on the electronvolt ($\text{eV}$) scale.

### 1) From latent heat to microscopic $\varepsilon$: nearest neighbours and double counting

For systems bonded by van der Waals forces, interactions with nearest neighbours are predominantly responsible for the material's cohesive energy, as the van der Waals potential, $V(r)$, decays rapidly with distance, proportional to $r^{-6}$. The latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, represents the energy required to break all intermolecular bonds in one mole of a substance. To relate this macroscopic quantity to the microscopic separation energy, $\varepsilon$, the number of nearest neighbours, $n$, must be considered. In liquids, the average number of nearest neighbours is approximately $n \approx 10$. In close-packed solids, this number is typically $n = 12$. Each intermolecular bond is shared between two atoms, necessitating a factor of $\frac{1}{2}$ to avoid double-counting when summing the total bond energy per mole. This leads to the relationship:

$$ L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon $$

Rearranging this expression allows for the calculation of the microscopic separation energy: $\varepsilon = \frac{2 L_v}{N_A n}$. For example, using Neon with a latent heat of vaporisation $L_v = 1.75\,\text{kJ mol}^{-1}$ and an average of $n \approx 10$ nearest neighbours (as it is liquid at its boiling point), the calculated separation energy $\varepsilon$ is approximately $0.004\,\text{eV}$. This value quantitatively demonstrates that van der Waals bonds are thousands of times weaker than typical strong bonds, which are on the electronvolt scale.

> **⚠️ Exam Alert!** The lecturer explicitly stated: "And this is not so different for a typical multiple choice question that you could get in the December multiple choice exam." This type of calculation, involving the relationship between latent heat and microscopic bond energy, is directly examinable. Students should be proficient in performing such calculations and understanding the physical implications of the result.

### 2) Three strong bond types: quick orientation

In addition to the weak van der Waals forces, three primary types of strong interatomic bonds exist, all characterised by bond strengths on the order of several electronvolts ($\text{eV}$). Ionic bonding arises from the complete transfer of electrons between atoms, creating oppositely charged ions (cations and anions) that are held together by strong Coulomb attraction. Covalent bonding involves the sharing of electron pairs between nuclei, forming strong, directional bonds. Metallic bonding is characterised by an array of positive ion cores immersed in a "sea" of delocalised valence electrons, resulting in strong, non-directional cohesive forces. While ionic bonding will be treated quantitatively, covalent and metallic bonding will be primarily discussed conceptually with key terminology.

### 3) Ionic bonding: long-range Coulomb attraction and lattice sums

Ionic bonds differ fundamentally from van der Waals interactions due to their long-range Coulomb attraction, which decays as $1/r$. This contrasts with the rapid $1/r^6$ decay of van der Waals forces. A simple model for the potential energy, $V(r)$, between two ions in an ionic solid includes a short-range repulsive term and a long-range Coulomb attractive term:

$$ V(r) = \frac{A}{r^p} - \frac{e^2}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r} $$

At a typical interionic separation of $r \approx 0.2\,\text{nm}$ (or $2\,\text{Å}$), the Coulomb attractive term is approximately $7\,\text{eV}$, confirming the strong nature of ionic bonds.

Because the Coulomb force is long-range, interactions beyond just nearest neighbours are significant and must be included in the total potential energy calculation for an ionic solid. This is illustrated by considering a one-dimensional alternating chain of positive and negative ions. The summation of these alternating attractive and repulsive interactions leads to a series of the form $1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{4} + \dots$, which converges to $\ln 2$. This geometric summation is encapsulated by the Madelung constant, $\alpha$, which accounts for the specific lattice geometry in the net electrostatic prefactor. The electrostatic potential for an ion in a lattice is thus given by:

$$ V(r)_{\text{electrostatic}} = -\frac{\alpha e^2}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r} $$

For a one-dimensional chain, $\alpha \approx 1.38$ (derived from $2\ln 2$). For a three-dimensional sodium chloride (NaCl) lattice, $\alpha \approx 1.75$. In practical calculations, such as those in an exam, the value of $\alpha$ would typically be provided, and students would be expected to utilise it in the formula.

The lattice energy is defined as the energy required to separate one mole of a crystalline ionic solid into its gaseous constituent ions. For macroscopic crystals, the properties are dominated by the bulk, and edge corrections are negligible.

### 4) Covalent bonding: sharing electrons and the Morse potential

Covalent bonds are formed by the sharing of a pair of electrons, typically with opposite spins, between two adjacent nuclei. This shared electron density between the positively charged nuclei creates a strong attractive force that holds the atoms together, overcoming the internuclear repulsion. The potential energy of a covalent bond is often described by the Morse potential:

$$ V(r) = D_e \left[ 1 - e^{a(r_e - r)} \right]^2 $$

Here, $r_e$ represents the equilibrium bond length, and $D_e$ is the dissociation energy, which is equivalent to the separation energy, $\varepsilon$, discussed for other bond types. It represents the depth of the potential well and the energy required to break the bond. Within the Morse potential well, molecules can occupy quantised vibrational energy levels. The absorption of infrared radiation by atmospheric molecules, such as carbon dioxide ($\text{CO}_2$) and nitrogen ($\text{N}_2$), excites these vibrational states, playing a critical role in maintaining Earth's surface temperature.

To illustrate the strength of covalent bonds, consider the dissociation temperature for a hydrogen molecule ($\text{H}_2$). By equating the average thermal energy of a particle, $\frac{3}{2}kT$, to the dissociation energy, $D_e$, we can estimate the temperature required to break the bond. For $\text{H}_2$, $D_e \approx 4.4\,\text{eV}$. Solving for $T$ yields an approximate temperature of $3 \times 10^4\,\text{K}$. This extremely high temperature demonstrates the immense strength of covalent bonds on thermal scales.

> **⚠️ Exam Alert!** The lecturer explicitly stated: "This is not so different from standard typical multiple choice questions that you'll get in December." Calculations involving the dissociation temperature of covalent bonds are directly examinable.

### 5) Metallic bonding: electron sea and trends

Metallic bonding is characterised by an array of positive ion cores immersed in a "sea" of delocalised valence electrons. These electrons are not bound to individual atoms but move freely throughout the metal lattice, providing strong, non-directional cohesive forces. The strength of metallic bonds is generally comparable to that of ionic and covalent bonds. The density of the electron sea influences the bond strength; for instance, magnesium ($\text{Mg}$), with two valence electrons, exhibits stronger metallic bonding than sodium ($\text{Na}$), which has only one. This difference is reflected in their respective latent heats of vaporisation: $128\,\text{kJ mol}^{-1}$ for $\text{Mg}$ compared to $97\,\text{kJ mol}^{-1}$ for $\text{Na}$, indicating that more energy is required to break the bonds in magnesium.

### 6) Thermal energy and the concept of temperature: starting kinetic theory of gases

The kinetic theory of gases provides a microscopic framework for understanding the macroscopic properties of gases, including temperature and pressure. An ideal gas is defined by several key assumptions: it consists of a large number ($N$) of identical molecules, which are treated as point particles with negligible size. All collisions, both between molecules and with the container walls, are perfectly elastic, and the motion of these molecules is completely random.

Pressure in a gas arises from the cumulative effect of countless molecular impacts on the container walls. Each collision involves a transfer of momentum. For a molecule striking a wall perpendicularly and elastically, the momentum transferred to the wall is $2mv_x$, where $m$ is the mass of the molecule and $v_x$ is its velocity component perpendicular to the wall. The number of molecules striking a wall of area $A$ in a time $t$ can be estimated as $\frac{1}{2} \frac{N}{V} A v_x t$, where $\frac{N}{V}$ is the number density of the gas, and the factor of $\frac{1}{2}$ accounts for, on average, half the molecules moving towards the wall. The full derivation of pressure and its link to temperature will be completed in the next lecture.

### Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

Slides detailing the Born-Landé lattice-energy derivation steps for $\text{NaCl}$ and the equilibrium condition were present in the lecture materials but were not covered in this session. Their results should not be integrated into the main narrative of this lecture.

## Key takeaways

The microscopic "bond energy" is represented by $\varepsilon$, the depth of the potential well, with $a_0$ being the equilibrium spacing at the potential minimum. For materials bonded by van der Waals forces, the latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, is linked to $\varepsilon$ through the number of nearest neighbours, $n$, and a $\frac{1}{2}$ double-counting factor: $L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon$. Typical van der Waals bond strengths are in the range of $10^{-3} \text{-} 10^{-2}\,\text{eV}$. Stronger bonds, including ionic, covalent, and metallic bonds, are on the $\text{eV}$ scale. Ionic attraction is a long-range $1/r$ interaction, requiring lattice sums accounted for by the Madelung constant, $\alpha$. Covalent bonds are well-described by the Morse potential, where the dissociation energy, $D_e$, is equivalent to $\varepsilon$. Dissociating a hydrogen molecule ($\text{H}_2$) requires temperatures around $3 \times 10^4\,\text{K}$, highlighting the extreme strength of covalent bonds. Metallic bonding results from a "sea" of delocalised electrons, and an increased number of valence electrons generally strengthens the bond, as seen by comparing magnesium ($\text{Mg}$) and sodium ($\text{Na}$). The foundations of kinetic theory involve ideal gas assumptions, where pressure originates from the momentum transfer during elastic molecular collisions. The initial steps for calculating the collision count have been established, with the complete derivation of pressure-temperature relations to follow in the next lecture.