Lecture 3: Interatomic Forces (part 2) - Springs, Potentials, and Linking to Latent Heat

0) Orientation, quick review, and admin

This lecture extends the two-term force model and Lennard-Jones picture introduced in Lecture 2, moving from a discussion of interatomic forces to potential energy. The primary goals for this session are to formalise the "atoms-on-springs" linearisation for small oscillations, derive the Lennard-Jones potential, interpret the separation energy $\varepsilon$ as bond strength, and connect $\varepsilon$ to macroscopic latent heat through the concept of nearest neighbours. The course materials include lecture slides and handwritten derivations, which often contain extra intermediate steps to aid understanding. Any content presented in the appendices of the slides is supplementary and not examinable, but may provide useful additional context.

The two-term force model describes the net interatomic force, $F(r)$, as a combination of short-range repulsion and longer-range attraction, typically expressed as $F(r) = A/r^m - B/r^n$. For matter to not collapse, the repulsive force must be shorter-range and steeper, meaning the exponent $m$ must be greater than $n$. The equilibrium separation distance, $a_0$, is defined as the point where the net force is zero ($F(a_0) = 0$). In the chosen sign convention, an attractive force is represented as negative in the direction of increasing $r$. While various attractive mechanisms exist (ionic, covalent, metallic, van der Waals), this lecture primarily focuses on van der Waals forces to establish quantitative links.

1) Small oscillations about equilibrium: atoms behave like masses on springs (SHM)

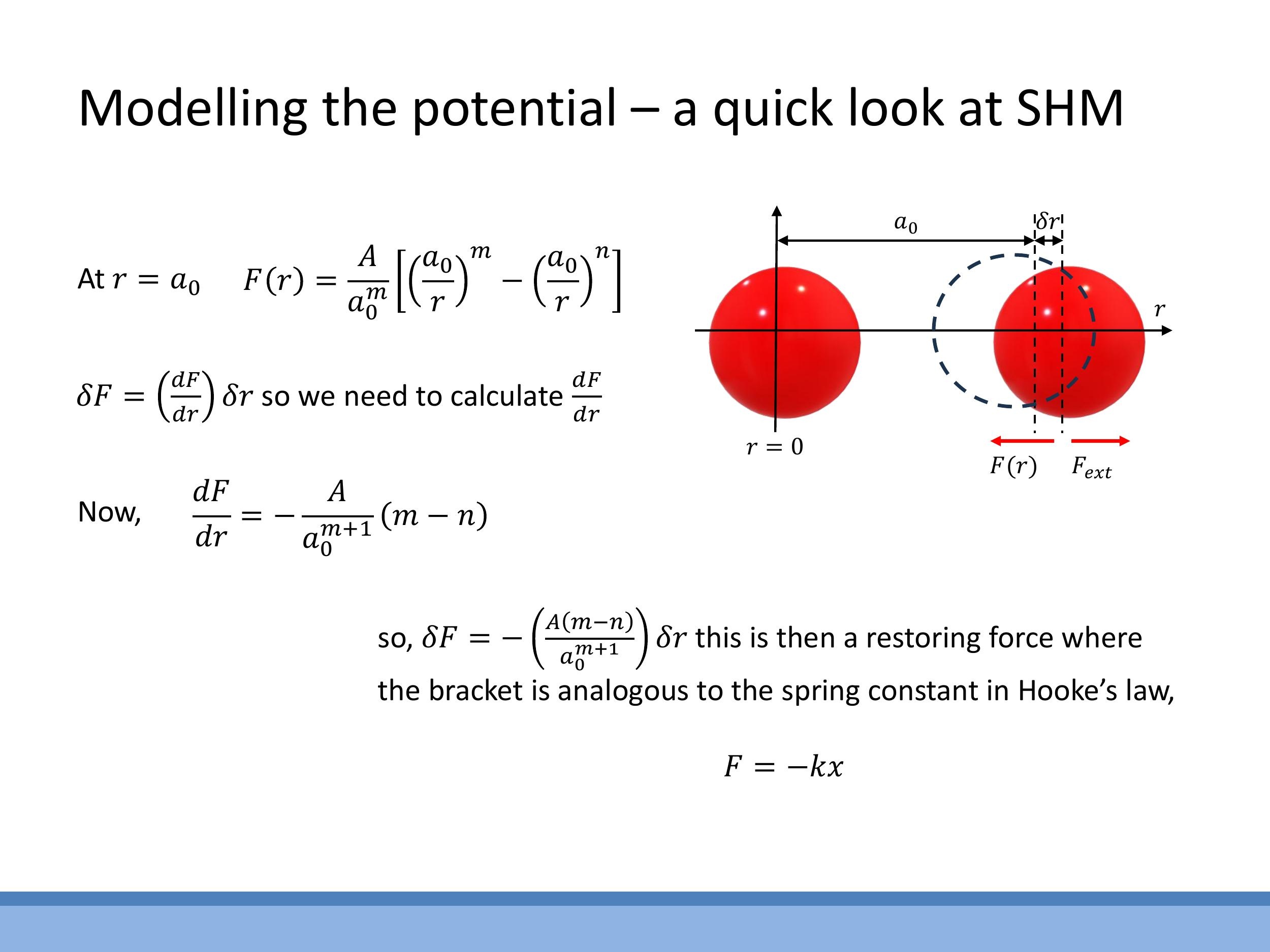

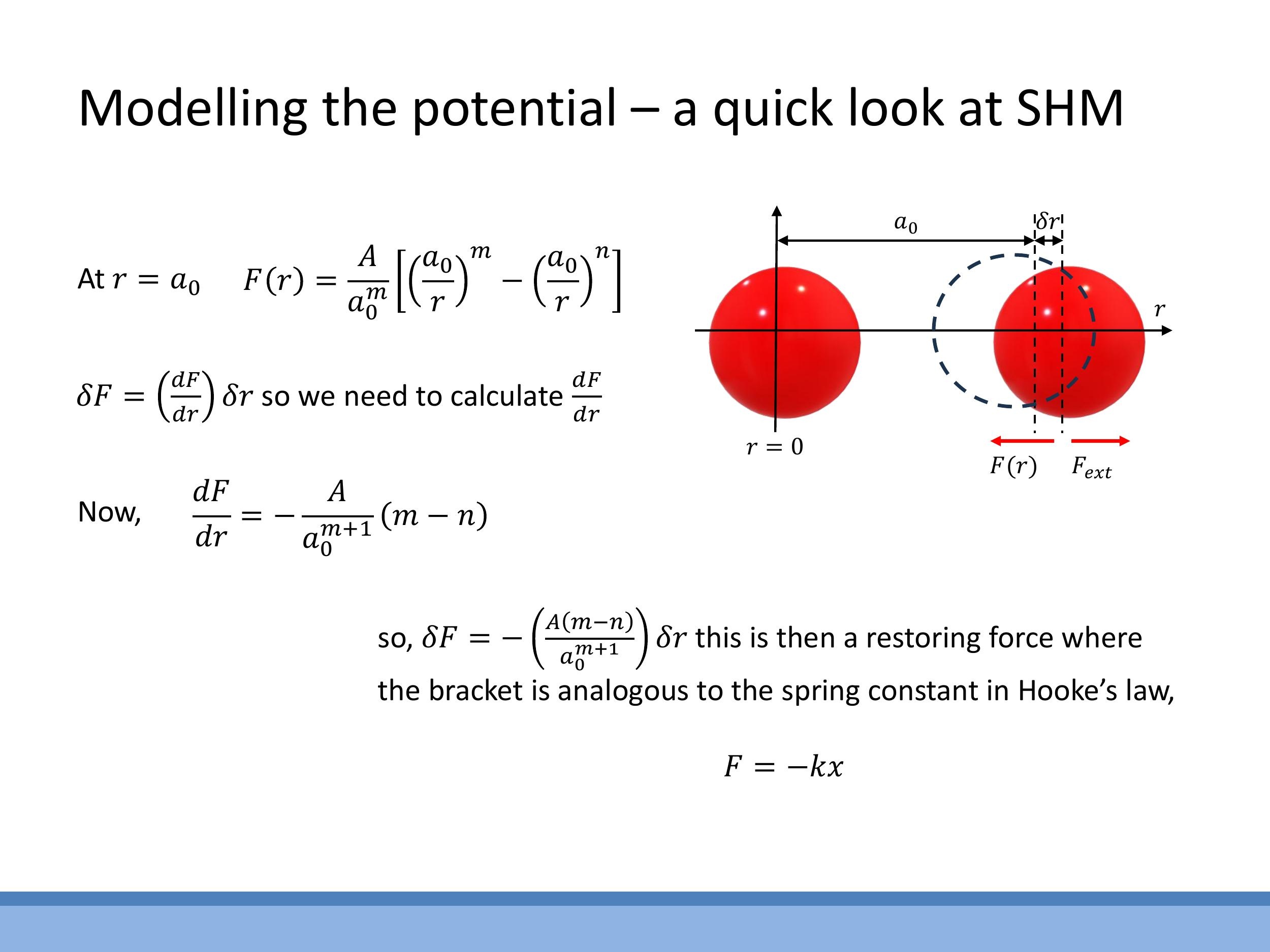

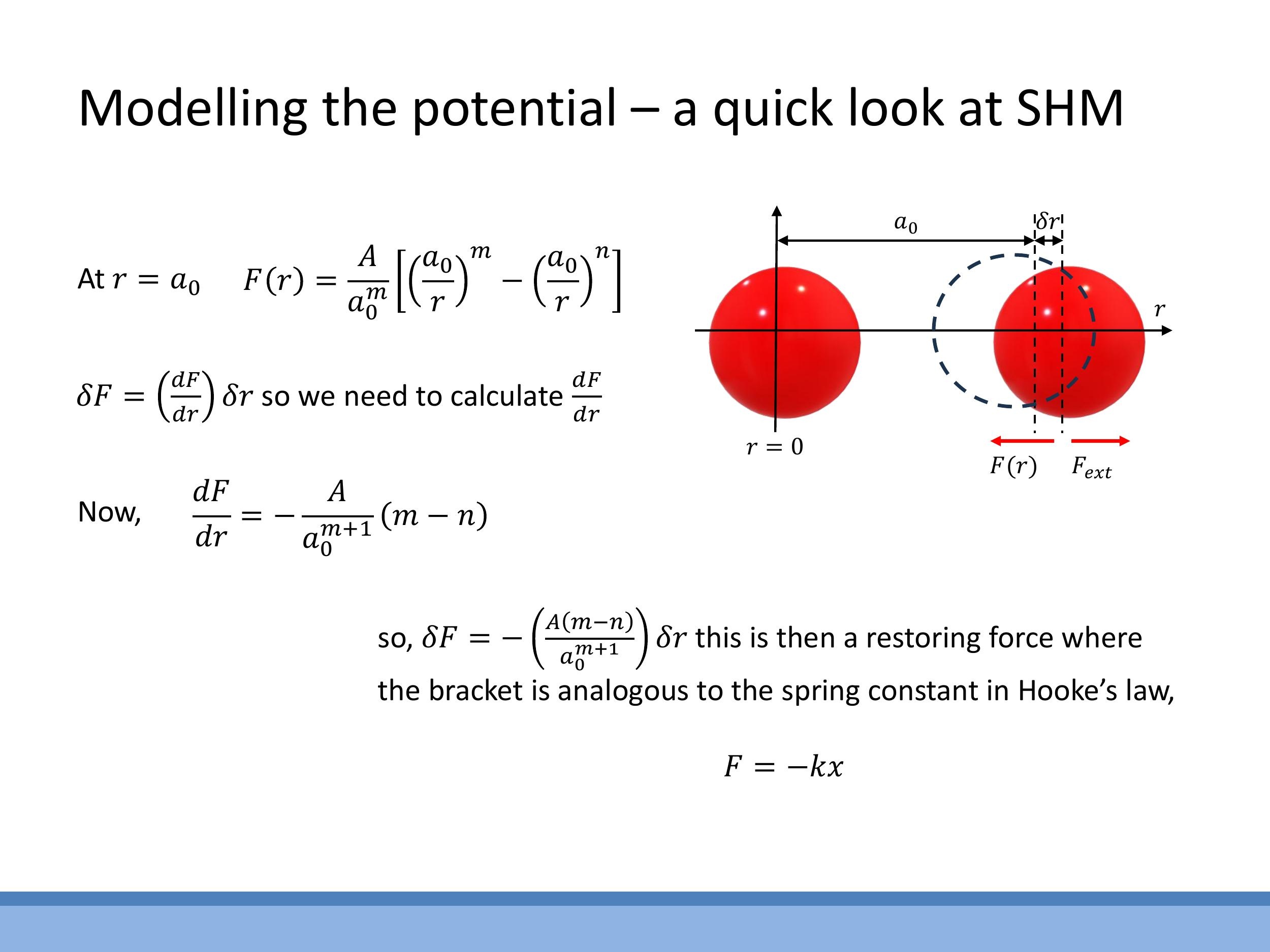

Near the equilibrium separation $a_0$, the interatomic force-distance curve can be approximated as locally linear. This means that small displacements, $\delta r$, from $a_0$ result in a restoring force that pushes or pulls the atoms back towards equilibrium, analogous to Hooke's Law for a spring. This linear, "spring-like" behaviour is only valid for small deviations; larger displacements lead to anharmonicity and can ultimately "break the spring" by overcoming the bond. A physical demonstration using magnets illustrates a stable equilibrium point with steep short-range repulsion and longer-range attraction, where small perturbations lead to a restoring force.

To formalise this, the change in force, $\delta F$, for a small displacement $\delta r$ can be expressed as $\delta F \approx (\frac{dF}{dr})\big| {r=a_0} \cdot \delta r$. By comparing this to Hooke's Law, $\delta F = -k\,\delta r$, the effective spring constant $k$ is identified as $k \equiv -(\frac{dF}{dr})\big| {r=a_0} $. Using the two-term force model $ F(r) = \frac{A}{a_0^m}\left[\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^m - \left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^n\right] $, differentiation with respect to $ r $ and evaluation at $ r = a_0 $ yields $ (\frac{dF}{dr})\big|_{r=a_0} = - \frac{A(m-n)}{a_0^{m+1}} $. Consequently, the effective spring constant is $ k = \frac{A(m-n)}{a_0^{m+1}} $. Physically, this expression shows that the "stiffness" of the interatomic bond depends on the strength of the interaction (parameter $ A $) and the characteristic ranges of the repulsive and attractive forces (exponents $ m $ and $ n$).

2) From force to potential: the Lennard-Jones well and the meaning of $\varepsilon$ and $a$

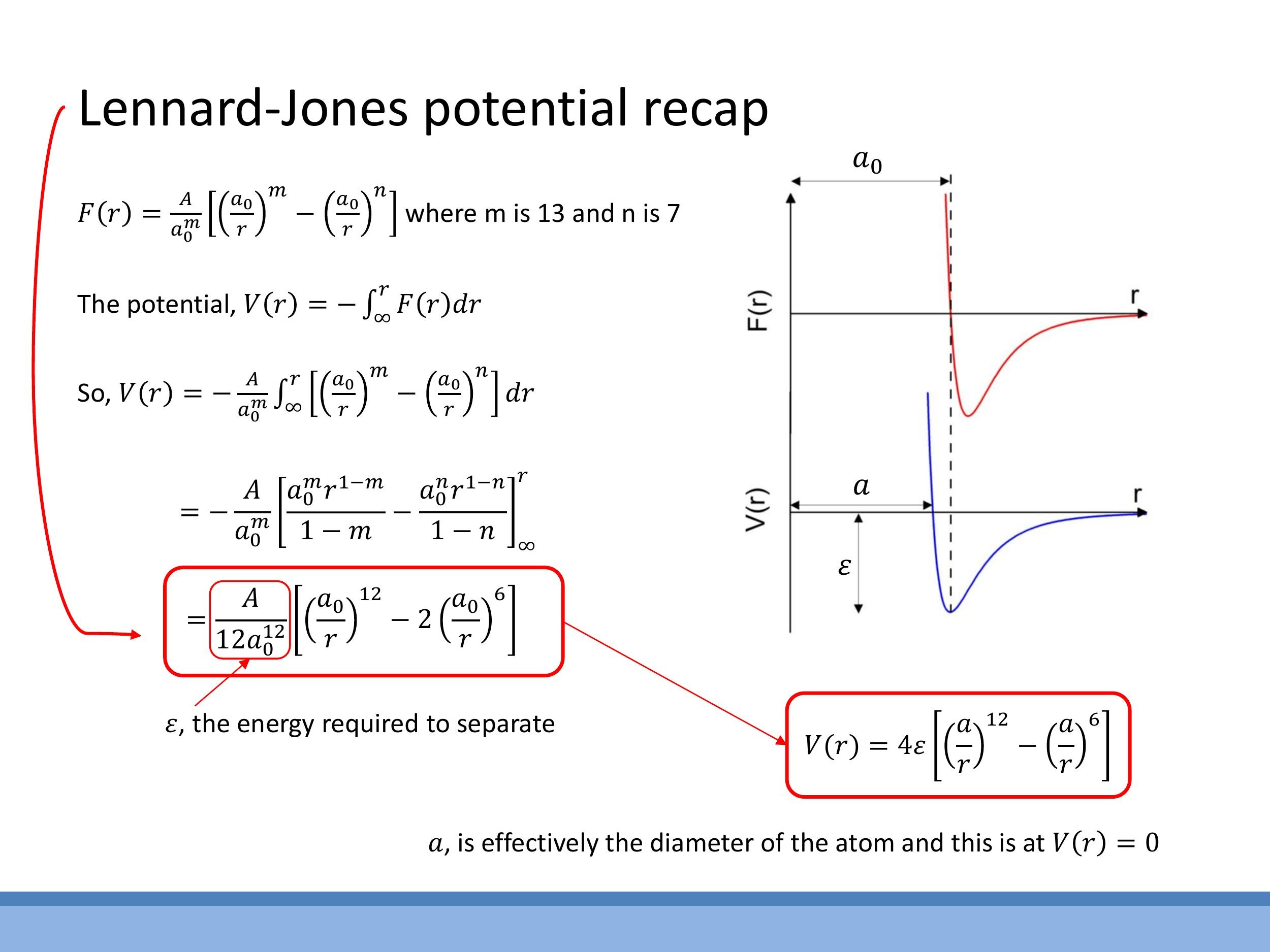

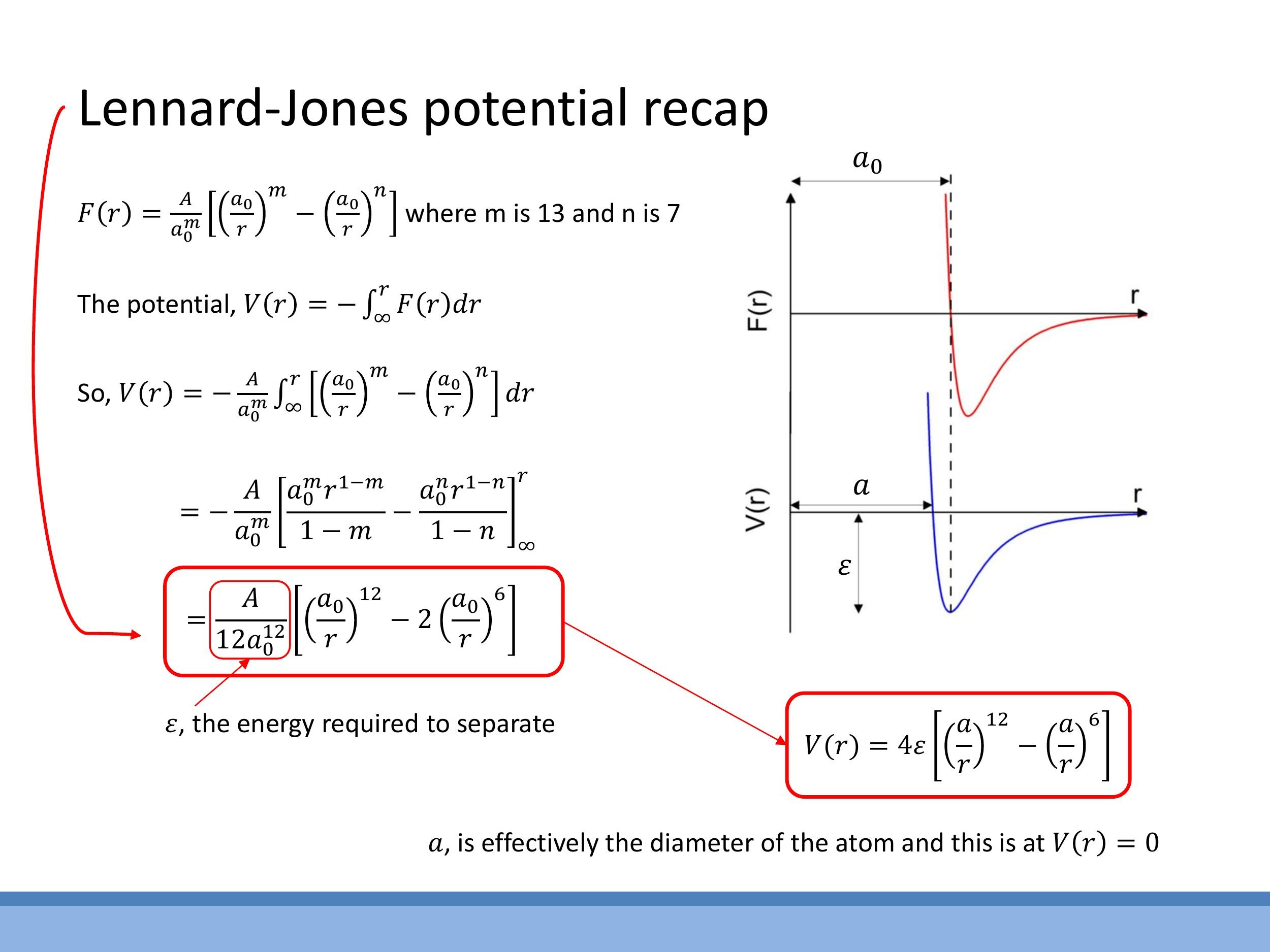

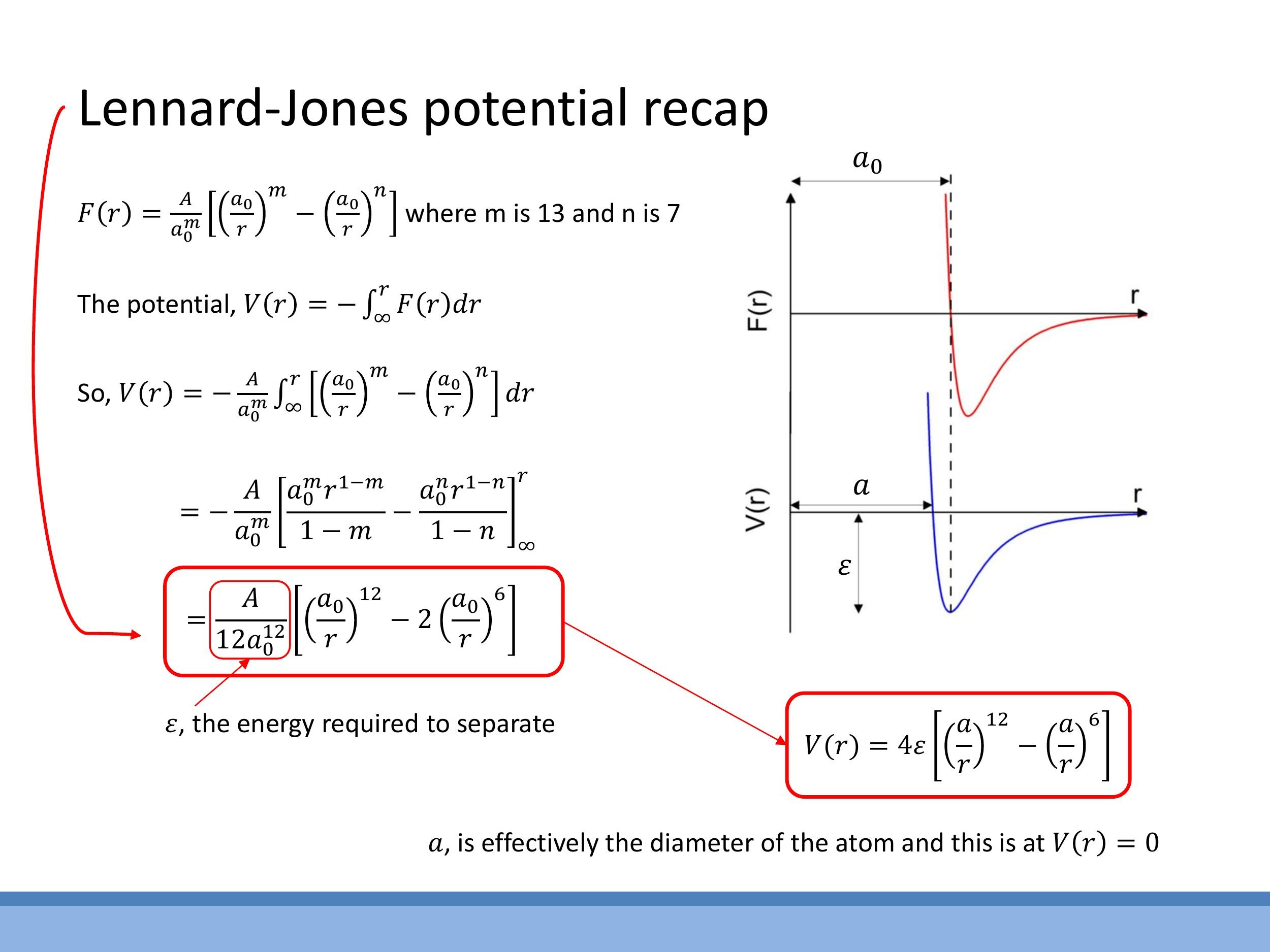

While $a_0$ represents a zero-force point, the concept of potential energy, $V(r)$, offers a more intuitive understanding of bond strength and stability, where $a_0$ corresponds to a minimum. The depth of this potential well is defined as the separation energy, $\varepsilon$, which is the energy required to separate the two bonded atoms to an infinite distance (i.e., to break the bond).

The potential energy $V(r)$ is derived by integrating the force $F(r)$ with respect to distance, using the definition $V(r) = -\int_r^\infty F(r') \, dr'$, where the boundary condition $ V(\infty) = 0 $ is applied. Using the previously established force form and the van der Waals exponents $ m=13 $ and $ n=7$, the integration yields one common form of the Lennard-Jones potential:

$$

V(r) = \frac{A}{12a_0^2}\left[\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^6\right]

$$

This can be re-expressed in a more standard textbook form using parameters $\varepsilon$ and $a$:

$$

V(r) = 4\varepsilon\left[\left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^6\right]

$$

In this standard form, $\varepsilon$ represents the well depth, directly quantifying the bond strength per pair of atoms. The parameter $a$ is the distance at which the potential energy $V(r)$ crosses zero, serving as a useful size parameter, akin to an "effective atomic diameter" in a hard-sphere model. The equilibrium separation $a_0$, where the force is zero and the potential is at its minimum, is related to $a$ by $a_0 = 2^{1/6}a$. The plotted curves show a steep repulsive wall at short distances, a minimum at $a_0$ with depth $\varepsilon$, and a long attractive tail that approaches zero at large separations, with the potential crossing zero at $r=a$.

3) Where van der Waals really matters: data and a real-world mechanism

3.1 Liquefaction of noble gases: polarisability and boiling points

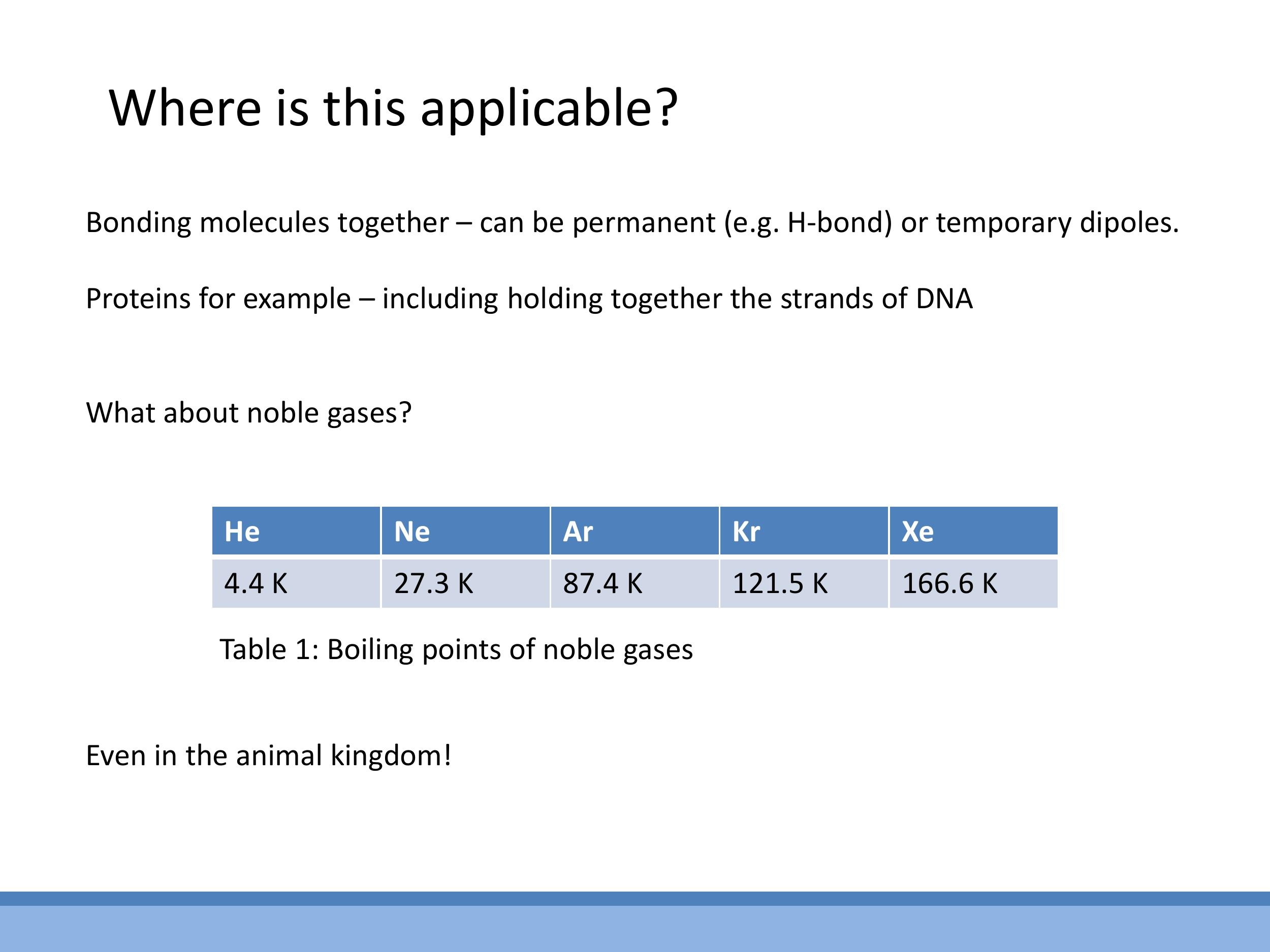

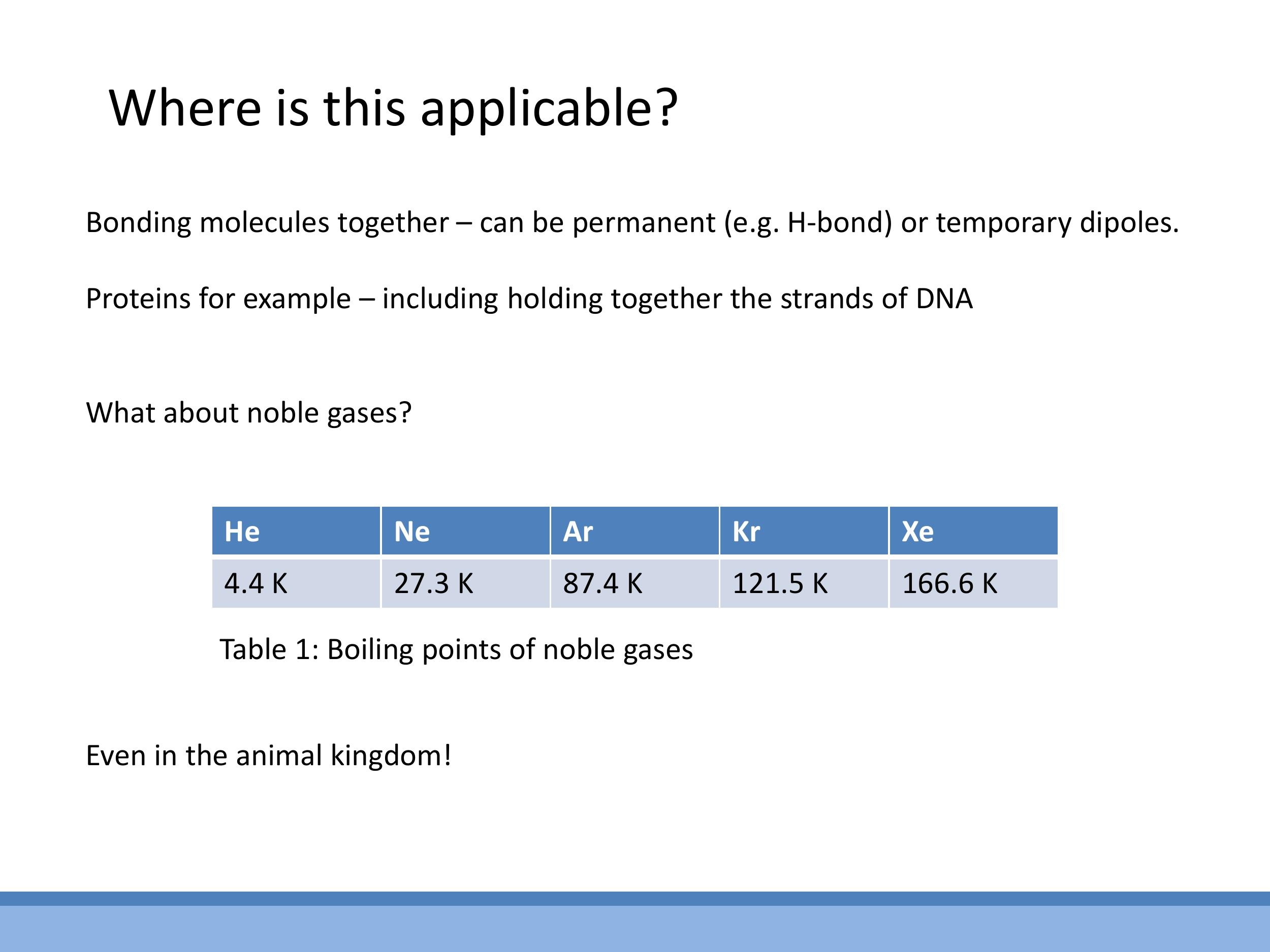

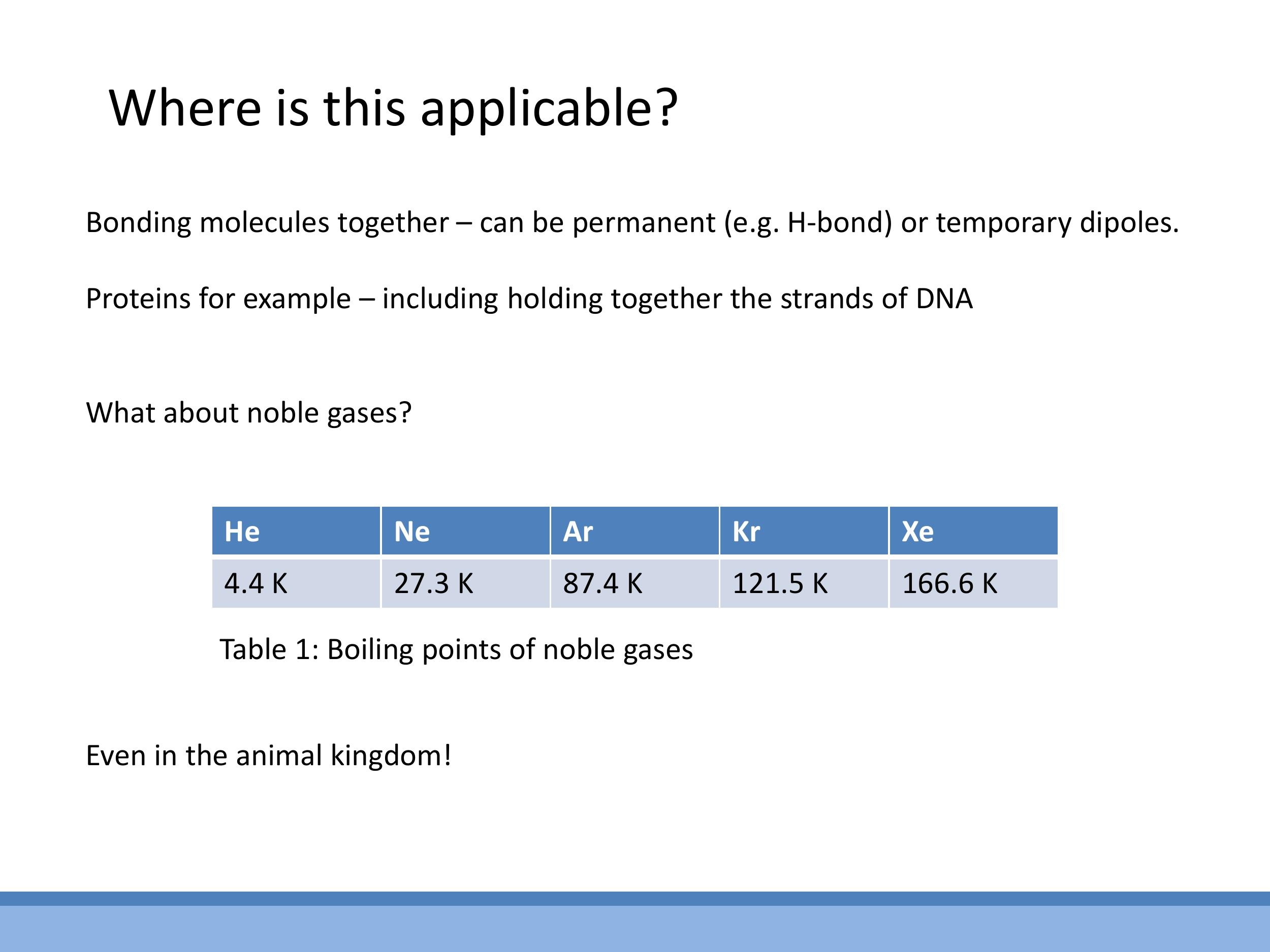

The liquefaction of noble gases presents a key puzzle: these elements have closed electron shells and are electrically neutral, yet they condense into liquids at low temperatures. This phenomenon is explained by van der Waals forces, specifically London dispersion forces. These forces arise from fluctuating instantaneous dipoles in one atom's electron cloud, which then induce temporary dipoles in neighbouring atoms, leading to a weak, transient attraction. The strength of these bonds is directly related to the polarisability of the atoms. As one moves down the noble gas group from helium (He) to xenon (Xe), the atoms become larger and their outer electrons are less tightly bound, making them more polarisable. This increased polarisability leads to stronger van der Waals bonds, which in turn requires more energy (and thus a higher temperature) to overcome, resulting in an observed increase in boiling points (He: $4.4 \, \text{K} $, Ne: $ 27.3 \, \text{K} $, Ar: $ 87.4 \, \text{K} $, Kr: $ 121.5 \, \text{K} $, Xe: $ 166.6 \, \text{K}$).

3.2 Gecko adhesion: many tiny weak bonds add up

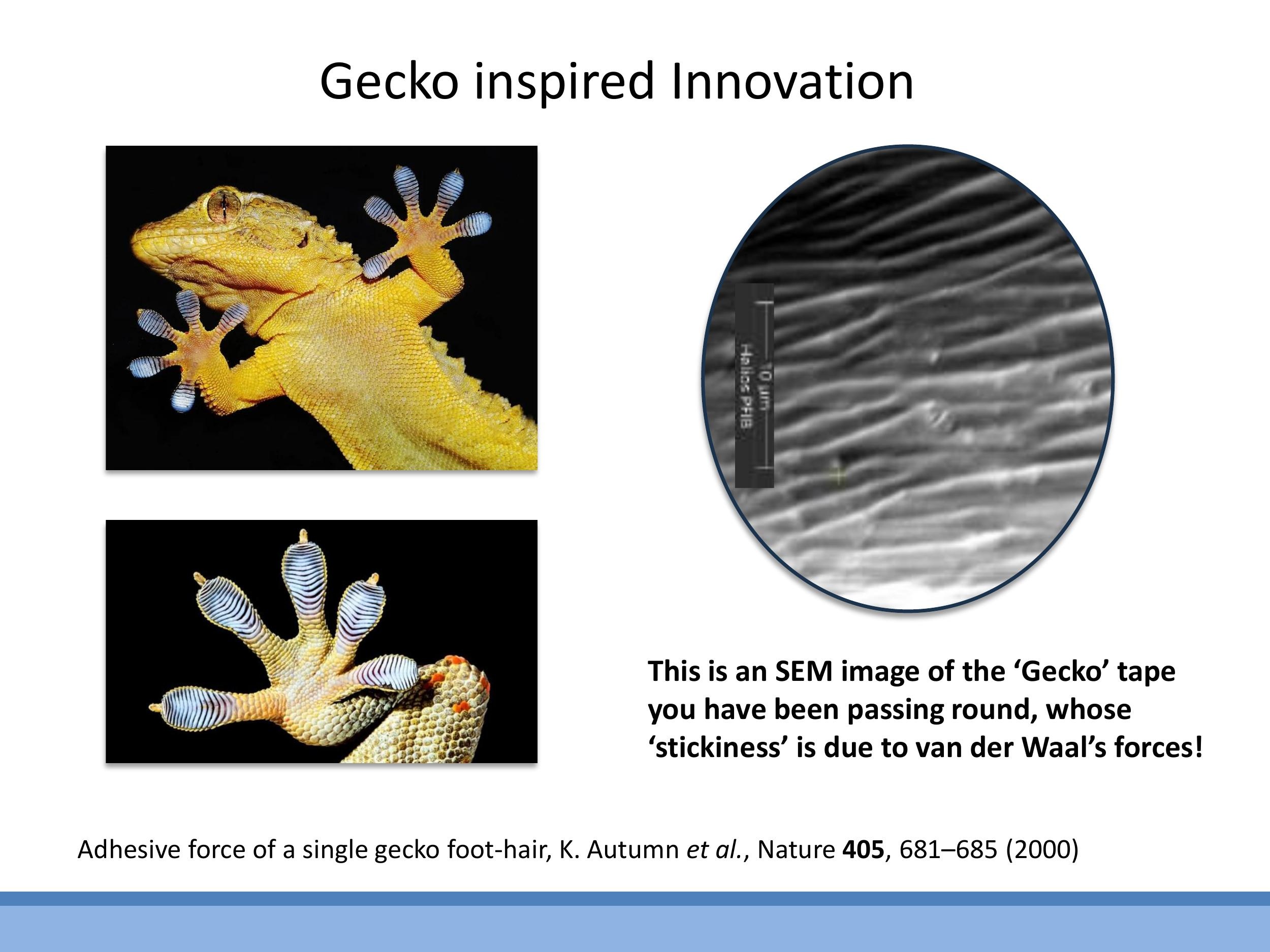

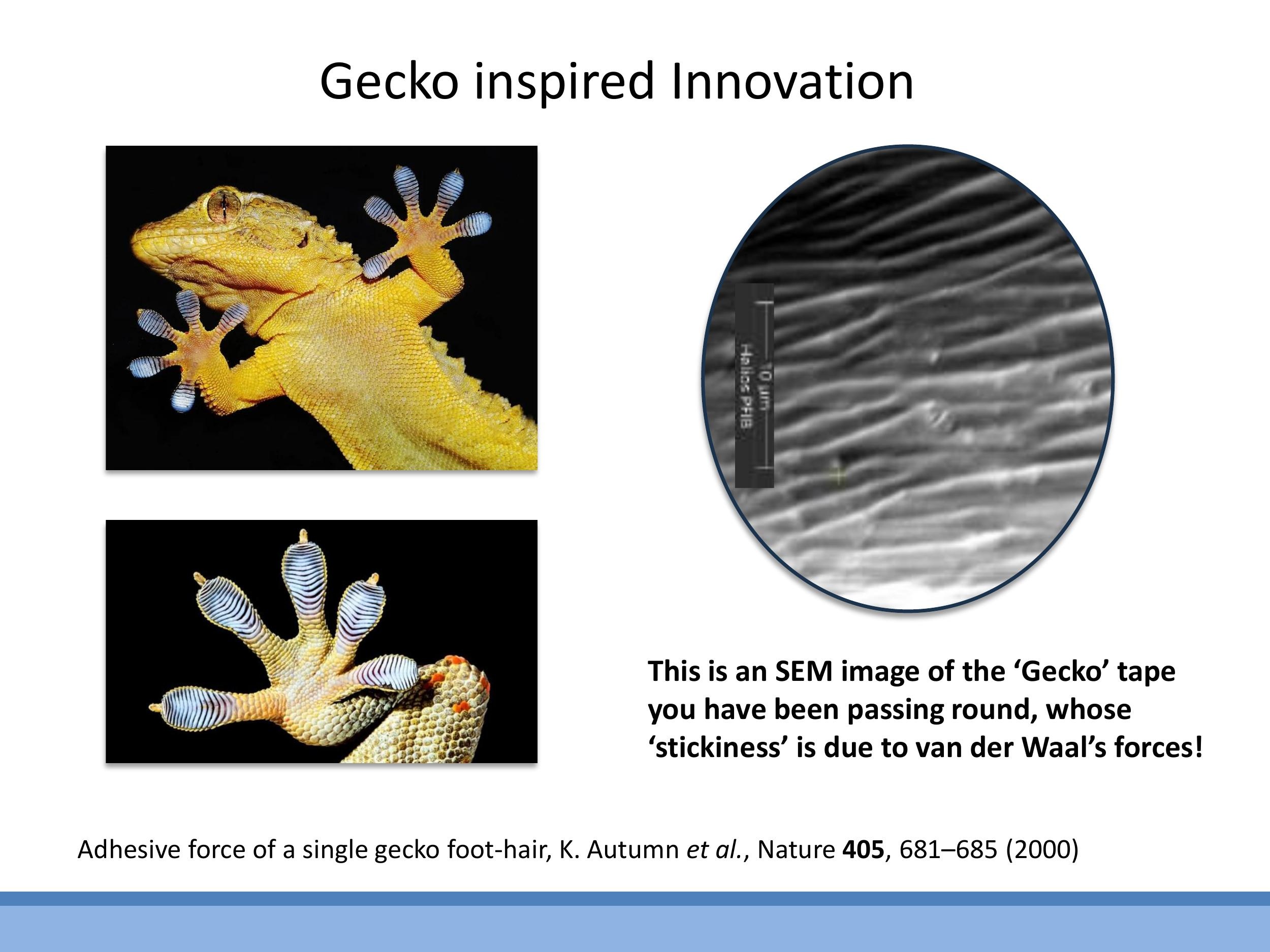

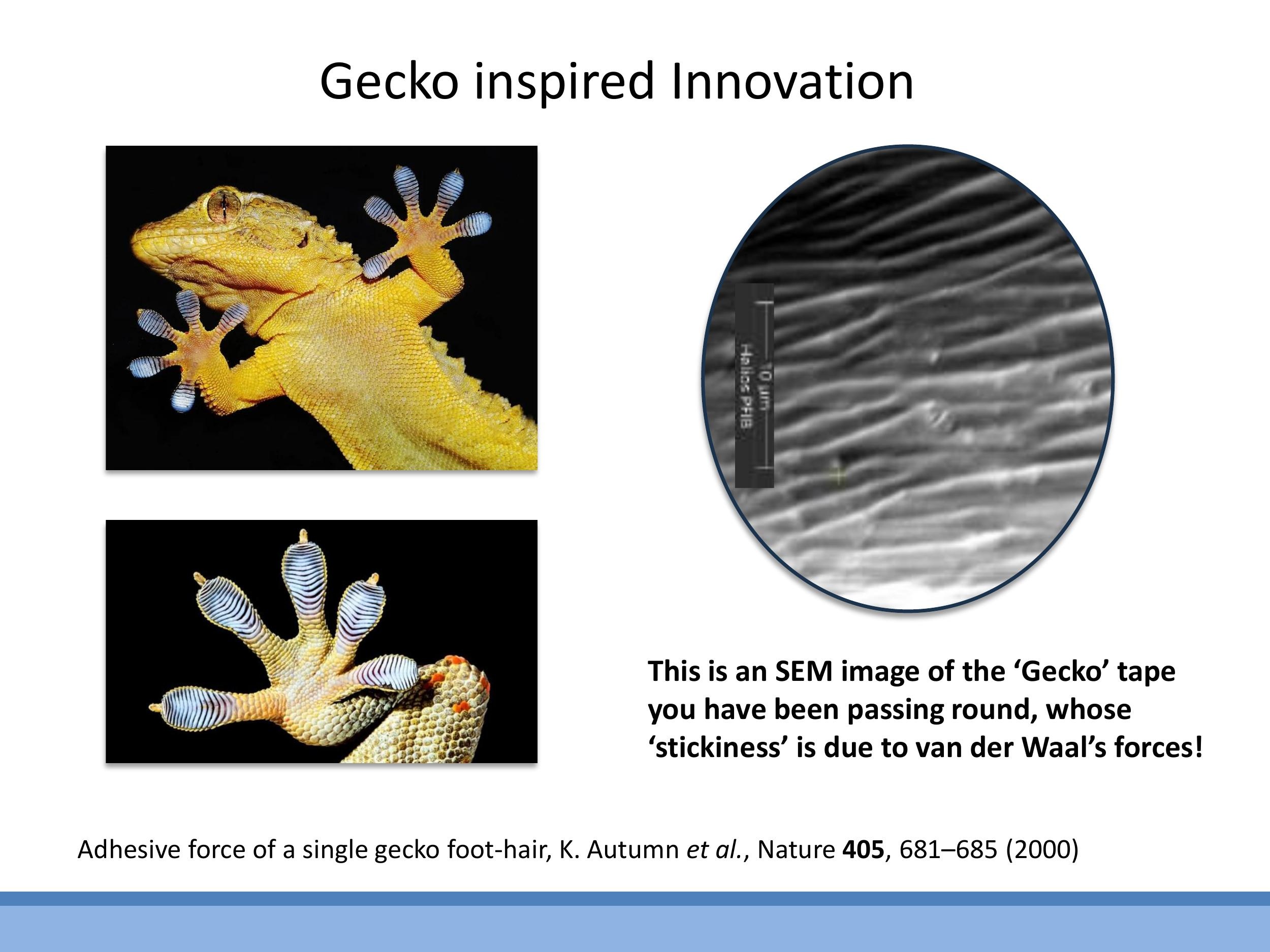

Another striking example of van der Waals forces in action is gecko adhesion. Geckos can cling to and walk up vertical surfaces due to the cumulative effect of millions of tiny van der Waals contacts. Their feet possess an enormous surface area, covered by microscopic and nanoscopic hair-like structures called setae. Each individual contact between a seta and a surface forms a very weak van der Waals bond, but the sheer number of these contacts generates a collective force strong enough to support the gecko's body weight. This principle has been mimicked in materials like "Gecko tape," which uses high-surface-area structures, as observed in scanning electron microscope (SEM) images, to achieve strong adhesion through van der Waals interactions.

4) Latent heat: the “hidden” energy of bond breaking/forming

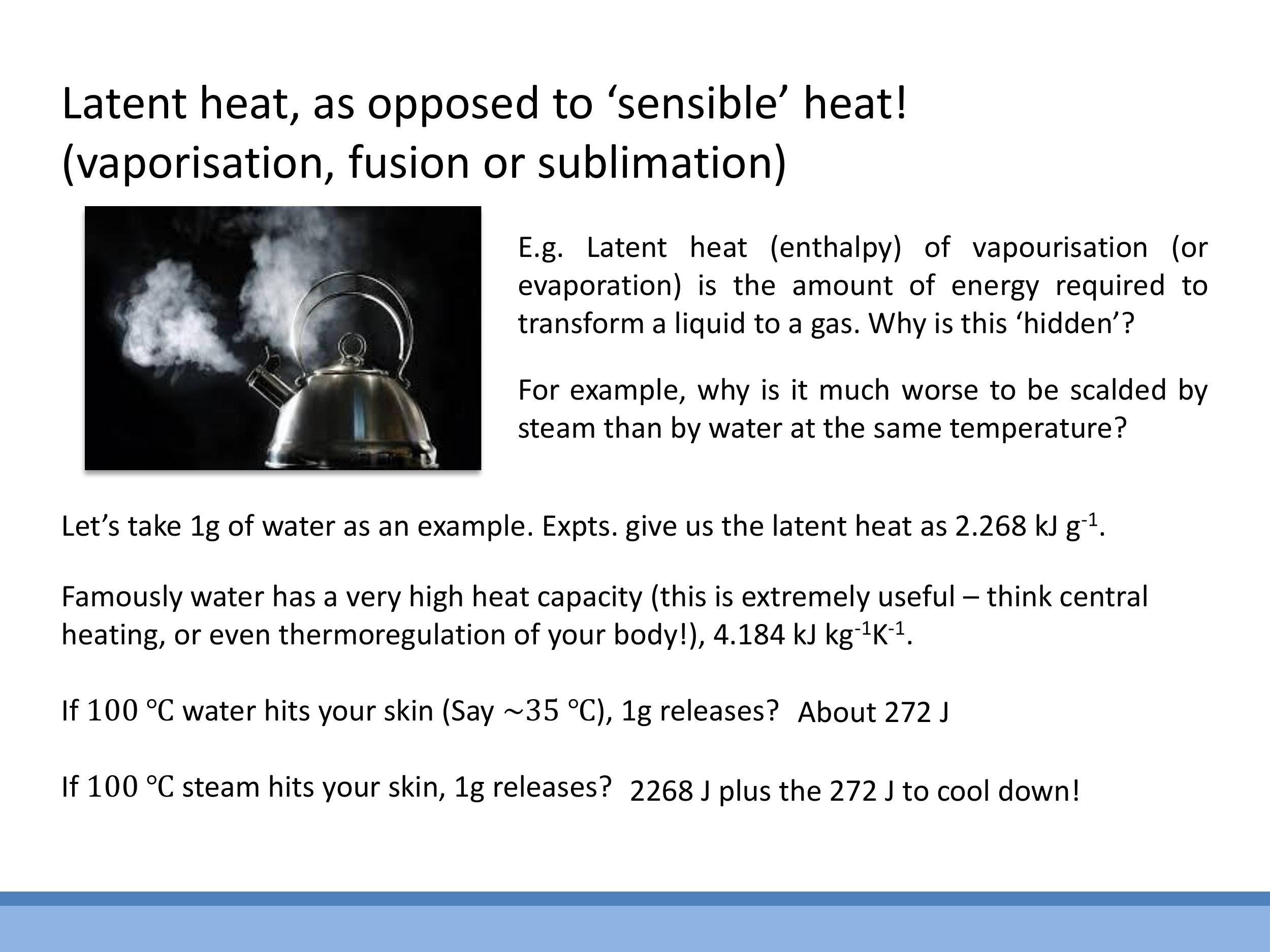

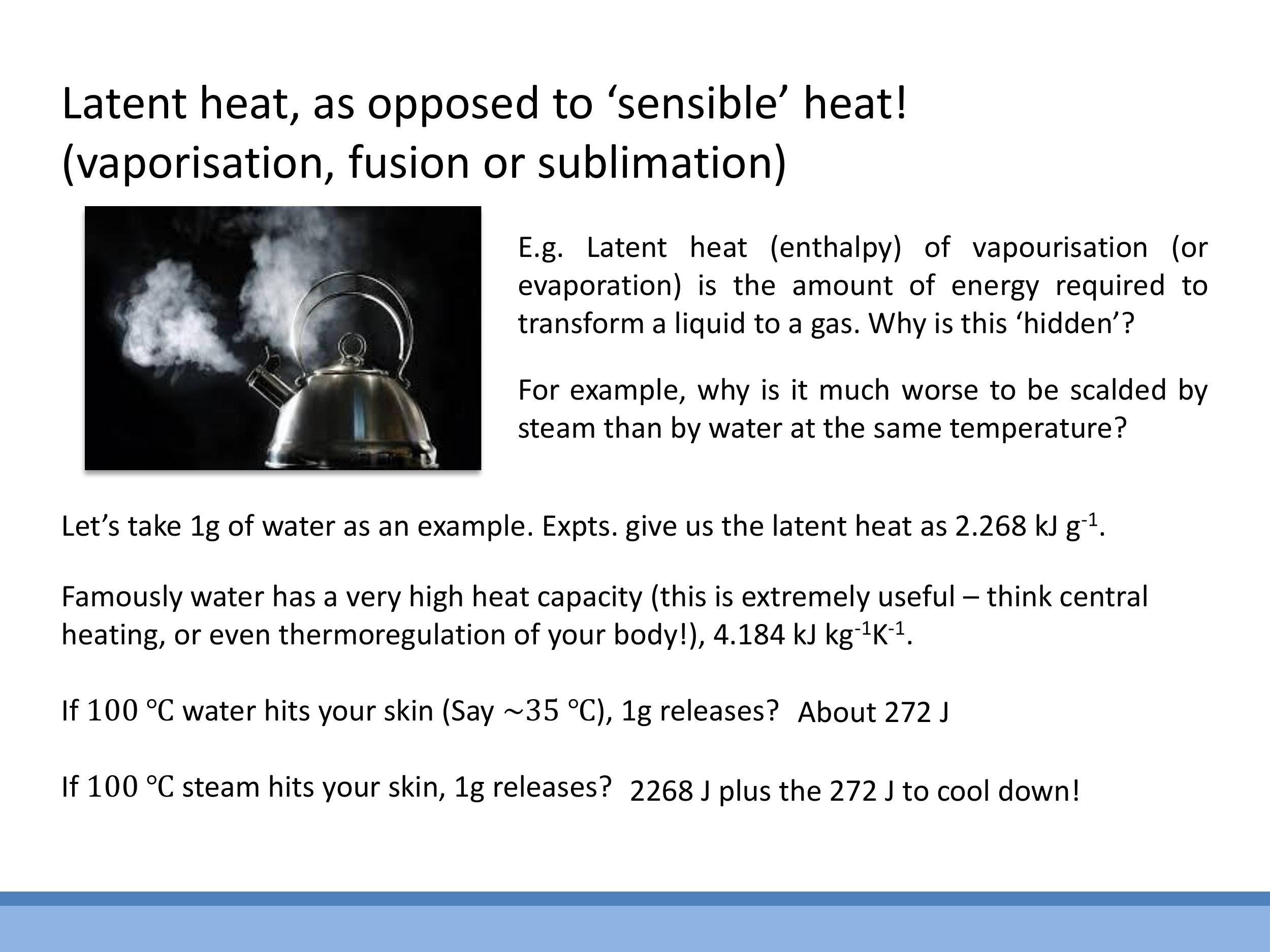

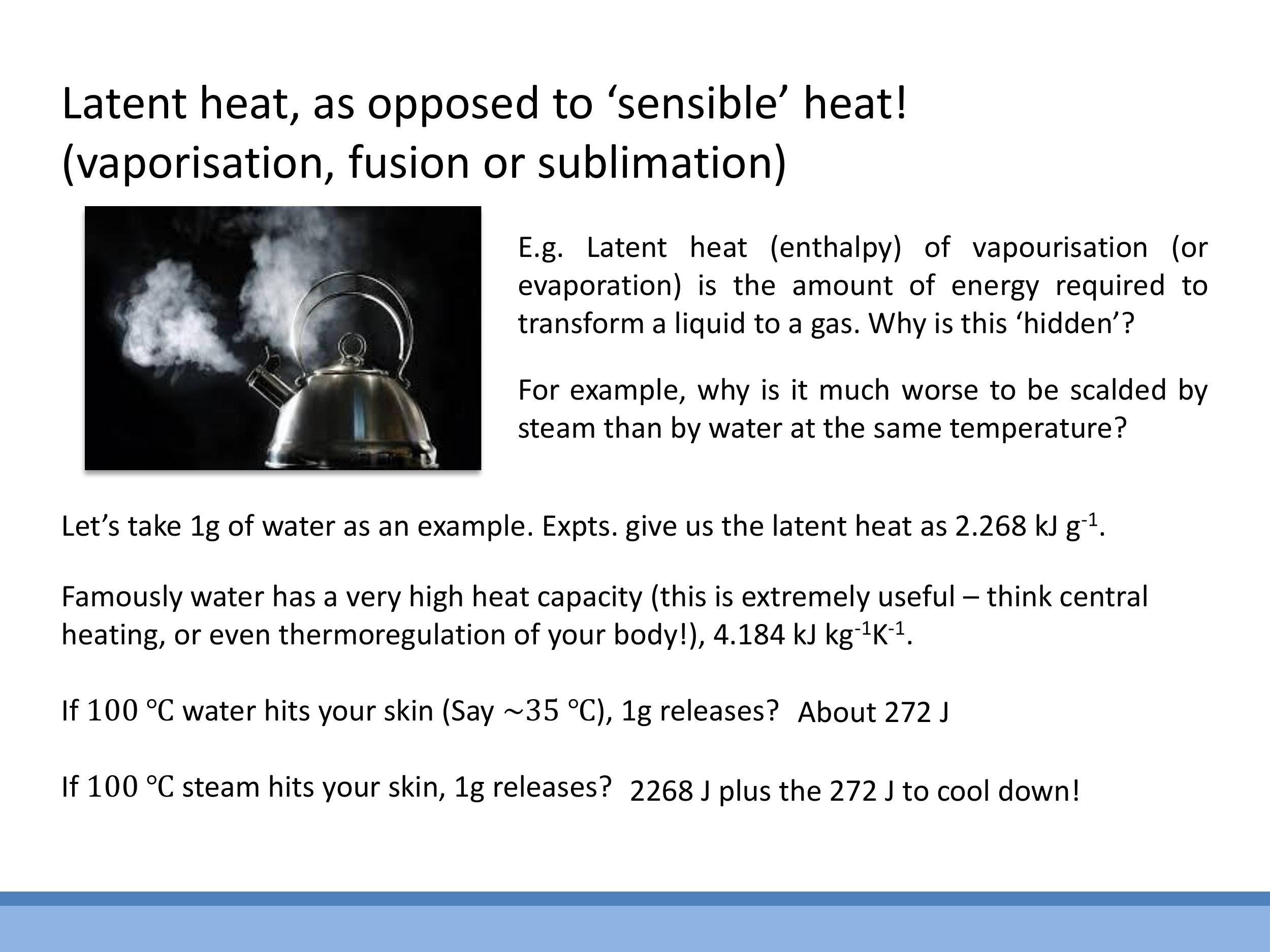

Latent heat refers to the energy absorbed or released by a substance during a phase change (e.g., vaporisation, fusion, or sublimation) at a constant temperature. This energy is "hidden" because it goes into changing the bonding state of the molecules, rather than increasing their kinetic energy, so the temperature of the substance does not change. This energy is fundamentally the macroscopic manifestation of breaking or forming intermolecular bonds.

To illustrate the magnitude of energy involved, consider the difference in scalding severity between $1 \, \text{g} $ of $ 100 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ water and $ 1 \, \text{g} $ of $ 100 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ steam when they contact skin at approximately $ 35 \, ^\circ\text{C} $. For $ 1 \, \text{g} $ of water, the sensible heat released as it cools to $ 35 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ is approximately $ 272 \, \text{J} $. In contrast, for $ 1 \, \text{g} $ of steam, two energy components are released: first, the latent heat of condensation as the steam turns into liquid water (approximately $ 2268 \, \text{J} $), and then the sensible heat as that newly condensed water cools to $ 35 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ (another $ 272 \, \text{J}$). Therefore, steam transfers roughly an order of magnitude more energy to the skin primarily due to the significant release of latent heat during condensation.

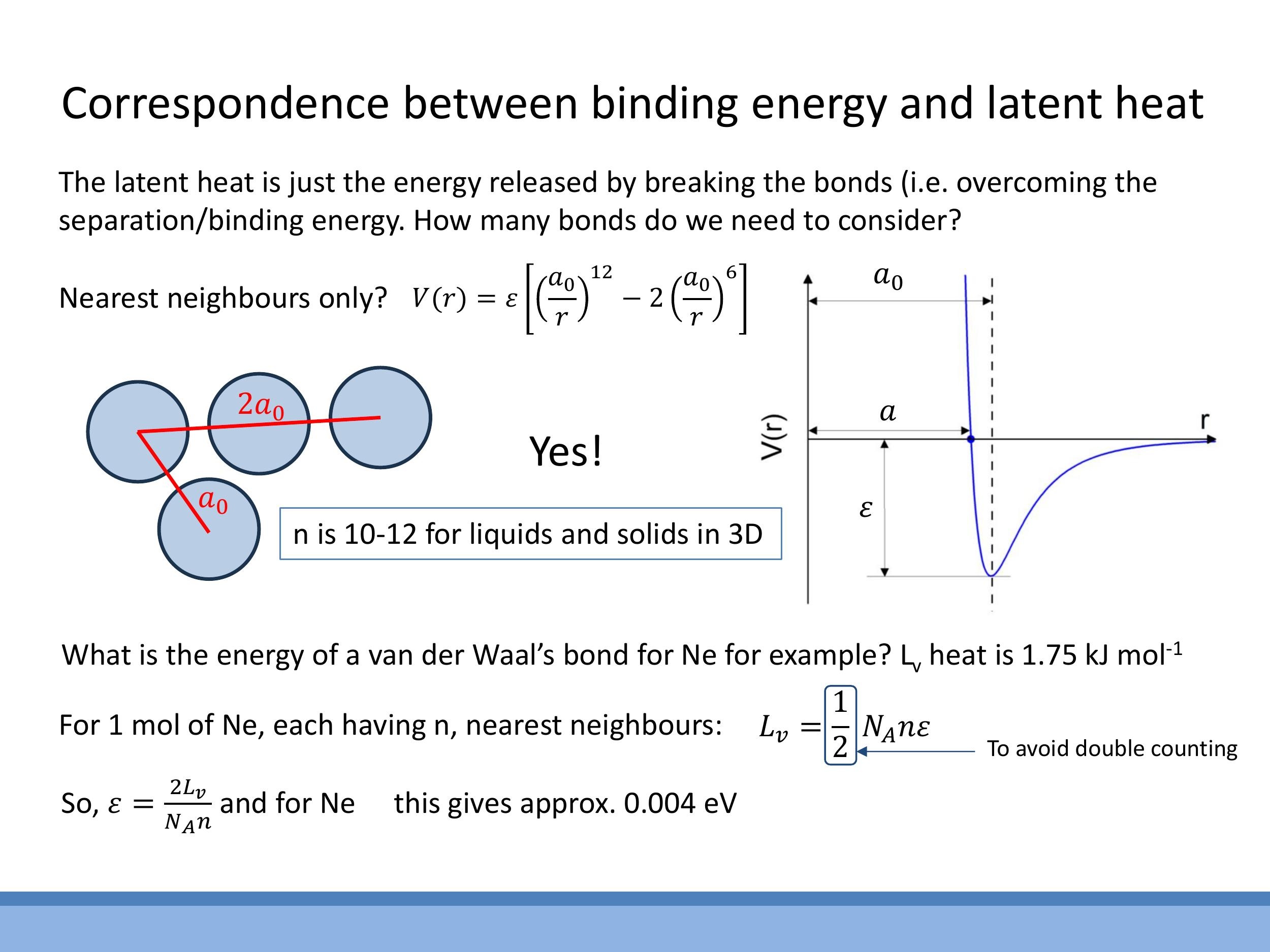

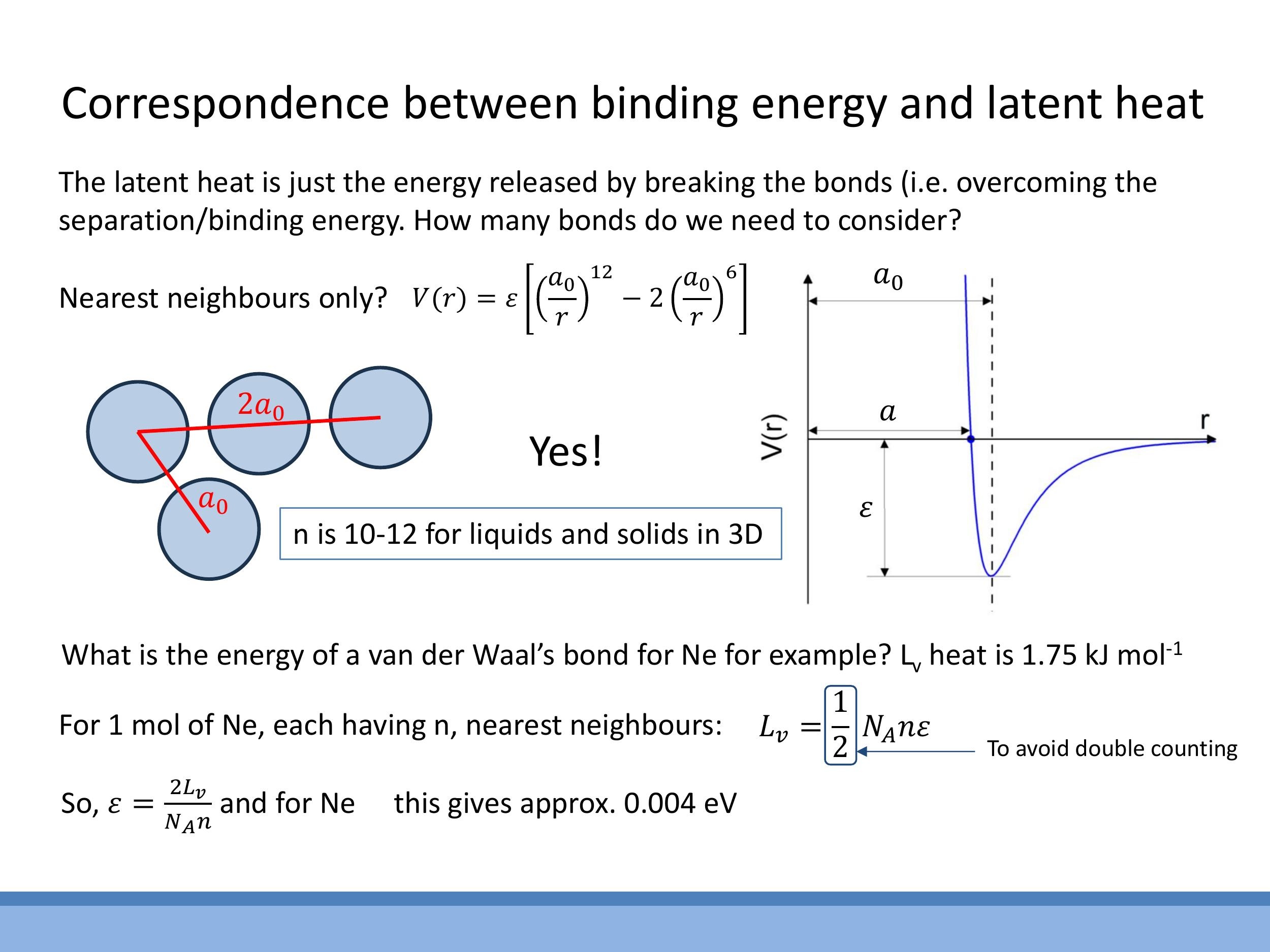

5) From macroscopic L_v to microscopic $\varepsilon$: counting neighbours

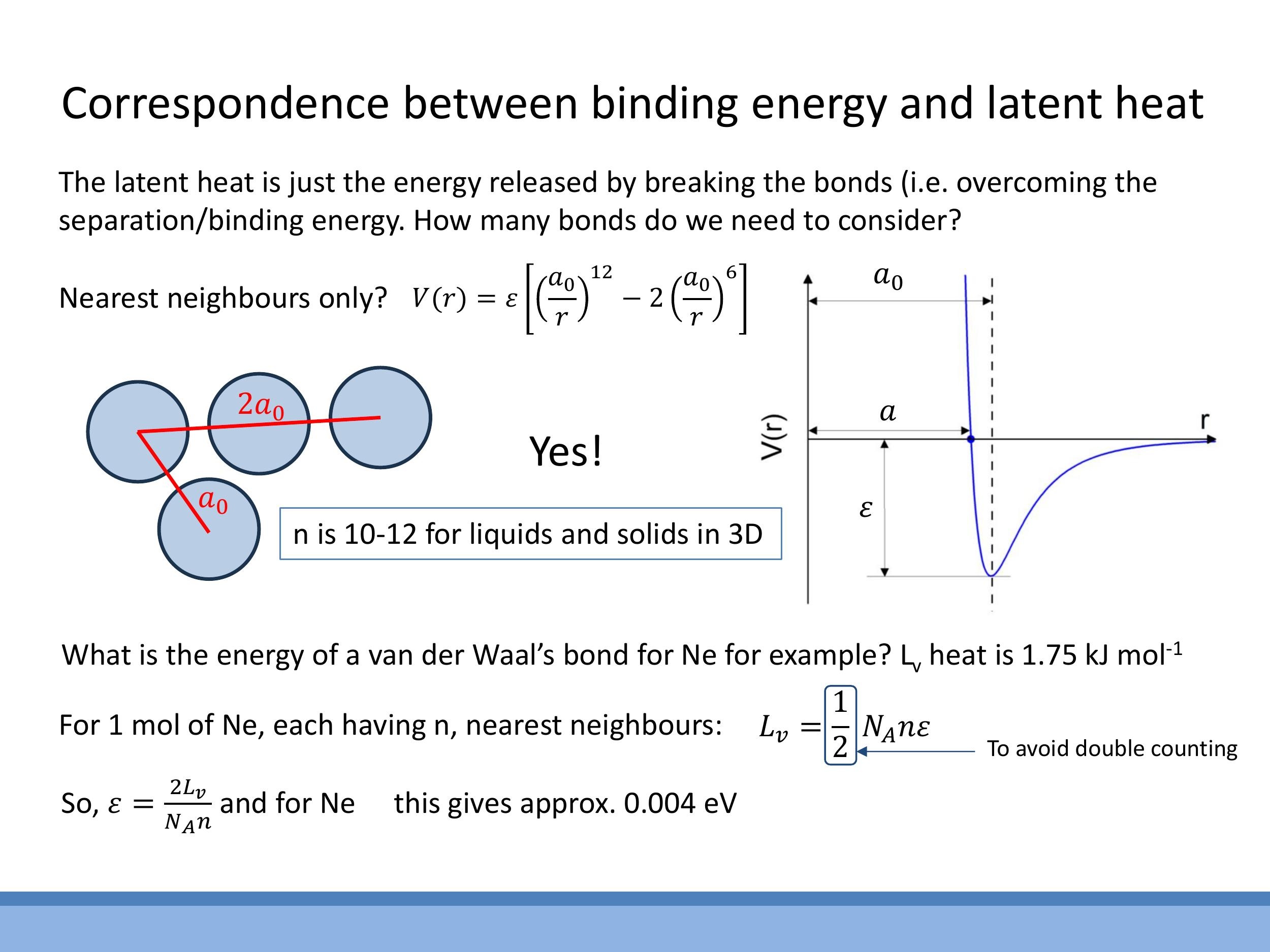

In condensed phases, the Lennard-Jones attractive potential decays rapidly (as $r^{-6}$), meaning that interactions with nearest neighbours dominate the total energy sum. This allows for a simplification where only the number of nearest neighbours is considered. Typical coordination numbers ($n$) are approximately $n \approx 10$ for liquids (representing an average) and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids. When linking macroscopic latent heat to microscopic bond energy, it is crucial to include a factor of $\frac{1}{2}$ to avoid double counting, as each interatomic bond is shared between two atoms.

The latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, for one mole of a substance, can thus be related to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ by the formula:

$$

L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon

$$

Rearranging this equation allows for the calculation of the microscopic bond strength from macroscopic data:

$$

\varepsilon = \frac{2 L_v}{N_A n}

$$

For example, for Neon, with a latent heat of vaporisation $L_v = 1.75 \, \text{kJ mol}^{-1} $ and assuming $ n \approx 10 $ (as it is a liquid at its boiling point), the calculated separation energy $ \varepsilon $ is approximately $ 0.004 \, \text{eV}$ per bond. This value quantitatively illustrates that van der Waals bonds are indeed thousands of times weaker than typical covalent or ionic bonds, which are on the order of several electron volts.

⚠️ Exam Alert! The lecturer explicitly stated: "And in a solid, that number is 12. So those numbers, and there are a few numbers I expect you remember for this course, and that's one of them." Students are expected to remember the typical nearest neighbour counts: $n \approx 10$ for liquids and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.

6) Consolidation: what the parameters tell you physically

The various parameters used in the interatomic force and potential models each carry distinct physical meanings crucial for understanding material properties. The equilibrium separation $a_0$ denotes the distance at which the net interatomic force is zero and the potential energy is at its minimum. The parameter $a$, found in the standard Lennard-Jones potential form, represents the distance at which the potential energy $V(r)$ is zero, serving as an effective atomic diameter or size parameter in the model. The separation energy $\varepsilon$ quantifies the depth of the potential well, representing the energy required to break a single bond or separate a pair of atoms. The effective spring constant $k$ describes the curvature of the potential at its minimum, indicating the stiffness of the interatomic "bond spring." These parameters help to reinforce the vast difference in bond strengths: van der Waals bonds are typically in the range of $10^{-3}$ to $10^{-2} \, \text{eV}$, whereas stronger bonds like ionic, covalent, and metallic bonds are on the order of several electron volts.

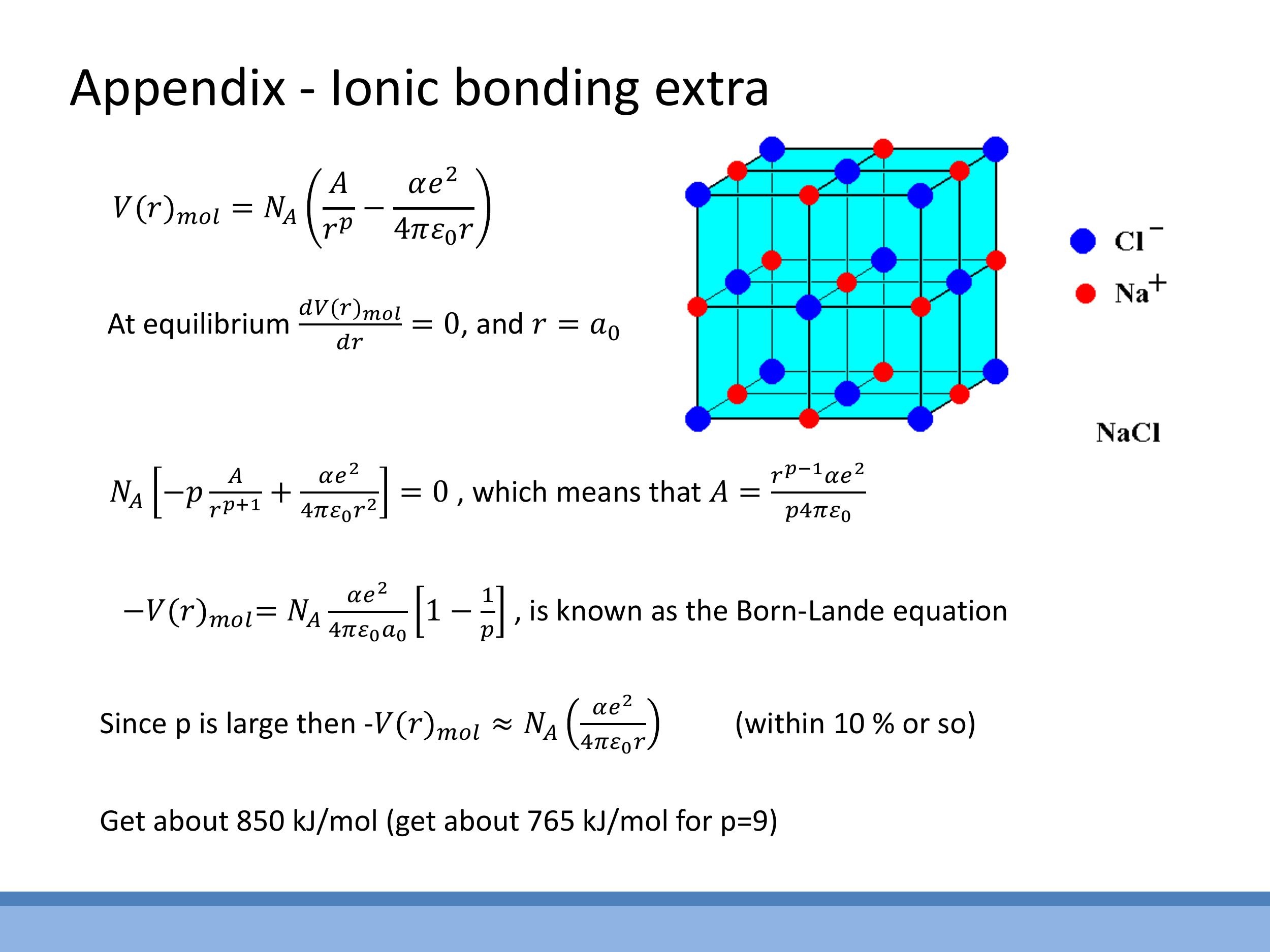

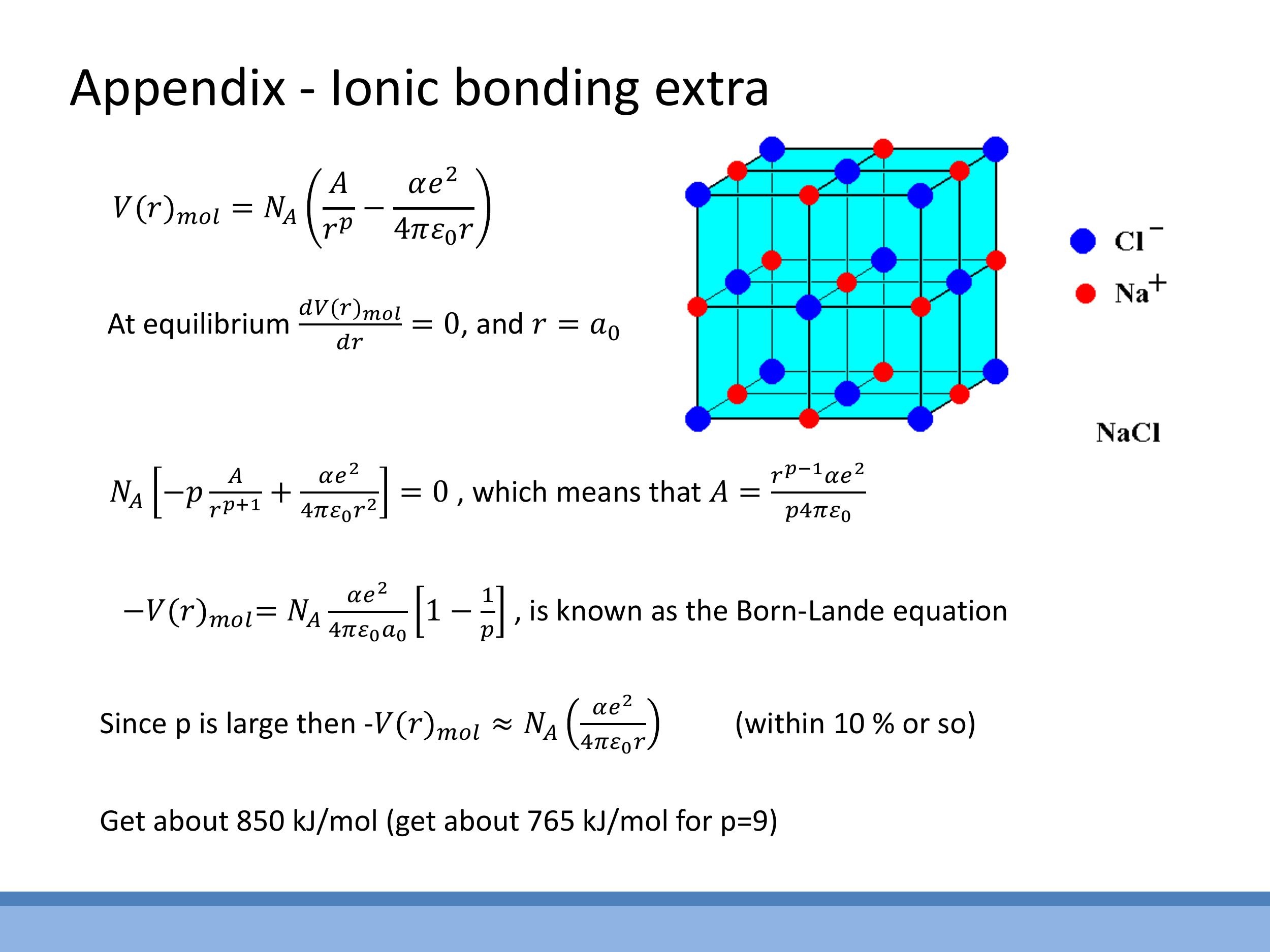

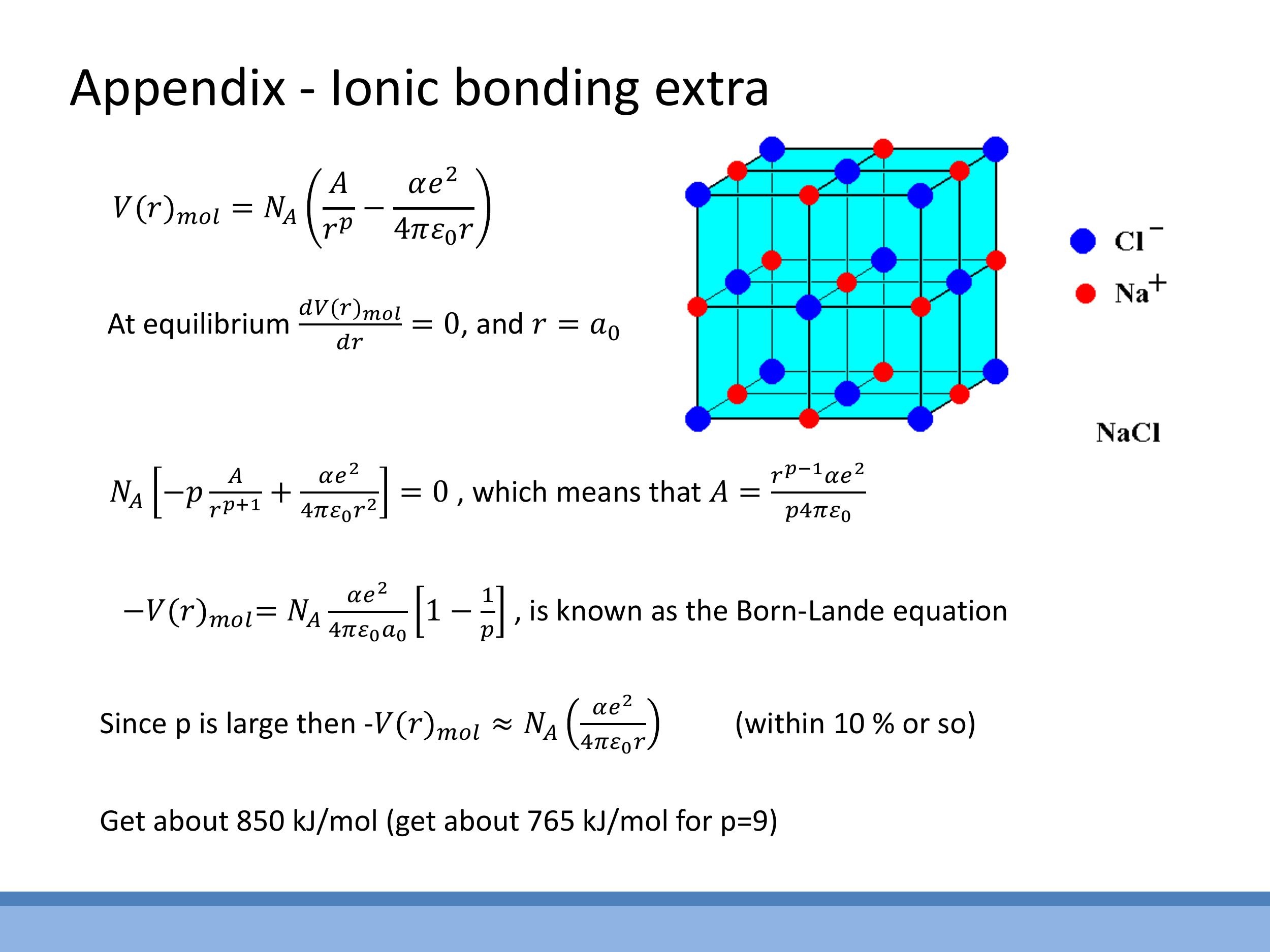

Side Note: This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

This appendix outlines the derivation of the Born-Landé equation for ionic solids. It involves calculating the electrostatic lattice sum, which introduces the Madelung constant $\alpha$ (e.g., approximately $1.75$ for an NaCl structure), and modelling short-range repulsion with a power law term, $A/r^p$. By setting the derivative of the potential to zero at equilibrium, the Born-Landé lattice energy formula can be derived.

Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

Slides detailing other bonding types such as ionic, covalent (Morse potential), and metallic bonding were present in the lecture slides but were not covered during this session and will be discussed in future lectures.

Key takeaways

Near equilibrium, interatomic forces can be linearly approximated, causing atoms to behave like masses on springs with an effective spring constant $k = \frac{A(m-n)}{a_0^{m+1}}$. Integrating the two-term force model yields the Lennard-Jones potential, where $\varepsilon$ is the bond strength (well depth), $a$ is the zero-potential distance (a size parameter), and $a_0$ is the equilibrium separation. Van der Waals forces, though weak per pair, explain phenomena like noble gas liquefaction and gecko adhesion through the cumulative effect of many weak bonds. Macroscopically, latent heat represents the energy involved in bond breaking or forming during phase changes; the latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, is linked to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ via $L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon$, where $n$ is the number of nearest neighbours. Typical coordination numbers are $n \approx 10$ for liquids and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.

## Lecture 3: Interatomic Forces (part 2) - Springs, Potentials, and Linking to Latent Heat

### 0) Orientation, quick review, and admin

This lecture extends the two-term force model and Lennard-Jones picture introduced in Lecture 2, moving from a discussion of interatomic forces to potential energy. The primary goals for this session are to formalise the "atoms-on-springs" linearisation for small oscillations, derive the Lennard-Jones potential, interpret the separation energy $\varepsilon$ as bond strength, and connect $\varepsilon$ to macroscopic latent heat through the concept of nearest neighbours. The course materials include lecture slides and handwritten derivations, which often contain extra intermediate steps to aid understanding. Any content presented in the appendices of the slides is supplementary and not examinable, but may provide useful additional context.

The two-term force model describes the net interatomic force, $F(r)$, as a combination of short-range repulsion and longer-range attraction, typically expressed as $F(r) = A/r^m - B/r^n$. For matter to not collapse, the repulsive force must be shorter-range and steeper, meaning the exponent $m$ must be greater than $n$. The equilibrium separation distance, $a_0$, is defined as the point where the net force is zero ($F(a_0) = 0$). In the chosen sign convention, an attractive force is represented as negative in the direction of increasing $r$. While various attractive mechanisms exist (ionic, covalent, metallic, van der Waals), this lecture primarily focuses on van der Waals forces to establish quantitative links.

### 1) Small oscillations about equilibrium: atoms behave like masses on springs (SHM)

Near the equilibrium separation $a_0$, the interatomic force-distance curve can be approximated as locally linear. This means that small displacements, $\delta r$, from $a_0$ result in a restoring force that pushes or pulls the atoms back towards equilibrium, analogous to Hooke's Law for a spring. This linear, "spring-like" behaviour is only valid for small deviations; larger displacements lead to anharmonicity and can ultimately "break the spring" by overcoming the bond. A physical demonstration using magnets illustrates a stable equilibrium point with steep short-range repulsion and longer-range attraction, where small perturbations lead to a restoring force.

To formalise this, the change in force, $\delta F$, for a small displacement $\delta r$ can be expressed as $\delta F \approx (\frac{dF}{dr})\big|_{r=a_0} \cdot \delta r$. By comparing this to Hooke's Law, $\delta F = -k\,\delta r$, the effective spring constant $k$ is identified as $k \equiv -(\frac{dF}{dr})\big|_{r=a_0}$. Using the two-term force model $F(r) = \frac{A}{a_0^m}\left[\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^m - \left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^n\right]$, differentiation with respect to $r$ and evaluation at $r = a_0$ yields $(\frac{dF}{dr})\big|_{r=a_0} = - \frac{A(m-n)}{a_0^{m+1}}$. Consequently, the effective spring constant is $k = \frac{A(m-n)}{a_0^{m+1}}$. Physically, this expression shows that the "stiffness" of the interatomic bond depends on the strength of the interaction (parameter $A$) and the characteristic ranges of the repulsive and attractive forces (exponents $m$ and $n$).

### 2) From force to potential: the Lennard-Jones well and the meaning of $\varepsilon$ and $a$

While $a_0$ represents a zero-force point, the concept of potential energy, $V(r)$, offers a more intuitive understanding of bond strength and stability, where $a_0$ corresponds to a minimum. The depth of this potential well is defined as the separation energy, $\varepsilon$, which is the energy required to separate the two bonded atoms to an infinite distance (i.e., to break the bond).

The potential energy $V(r)$ is derived by integrating the force $F(r)$ with respect to distance, using the definition $V(r) = -\int_r^\infty F(r')\,dr'$, where the boundary condition $V(\infty) = 0$ is applied. Using the previously established force form and the van der Waals exponents $m=13$ and $n=7$, the integration yields one common form of the Lennard-Jones potential:

$$ V(r) = \frac{A}{12a_0^2}\left[\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^6\right] $$

This can be re-expressed in a more standard textbook form using parameters $\varepsilon$ and $a$:

$$ V(r) = 4\varepsilon\left[\left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^6\right] $$

In this standard form, $\varepsilon$ represents the well depth, directly quantifying the bond strength per pair of atoms. The parameter $a$ is the distance at which the potential energy $V(r)$ crosses zero, serving as a useful size parameter, akin to an "effective atomic diameter" in a hard-sphere model. The equilibrium separation $a_0$, where the force is zero and the potential is at its minimum, is related to $a$ by $a_0 = 2^{1/6}a$. The plotted curves show a steep repulsive wall at short distances, a minimum at $a_0$ with depth $\varepsilon$, and a long attractive tail that approaches zero at large separations, with the potential crossing zero at $r=a$.

### 3) Where van der Waals really matters: data and a real-world mechanism

#### 3.1 Liquefaction of noble gases: polarisability and boiling points

The liquefaction of noble gases presents a key puzzle: these elements have closed electron shells and are electrically neutral, yet they condense into liquids at low temperatures. This phenomenon is explained by van der Waals forces, specifically London dispersion forces. These forces arise from fluctuating instantaneous dipoles in one atom's electron cloud, which then induce temporary dipoles in neighbouring atoms, leading to a weak, transient attraction. The strength of these bonds is directly related to the polarisability of the atoms. As one moves down the noble gas group from helium (He) to xenon (Xe), the atoms become larger and their outer electrons are less tightly bound, making them more polarisable. This increased polarisability leads to stronger van der Waals bonds, which in turn requires more energy (and thus a higher temperature) to overcome, resulting in an observed increase in boiling points (He: $4.4\,\text{K}$, Ne: $27.3\,\text{K}$, Ar: $87.4\,\text{K}$, Kr: $121.5\,\text{K}$, Xe: $166.6\,\text{K}$).

#### 3.2 Gecko adhesion: many tiny weak bonds add up

Another striking example of van der Waals forces in action is gecko adhesion. Geckos can cling to and walk up vertical surfaces due to the cumulative effect of millions of tiny van der Waals contacts. Their feet possess an enormous surface area, covered by microscopic and nanoscopic hair-like structures called setae. Each individual contact between a seta and a surface forms a very weak van der Waals bond, but the sheer number of these contacts generates a collective force strong enough to support the gecko's body weight. This principle has been mimicked in materials like "Gecko tape," which uses high-surface-area structures, as observed in scanning electron microscope (SEM) images, to achieve strong adhesion through van der Waals interactions.

### 4) Latent heat: the “hidden” energy of bond breaking/forming

Latent heat refers to the energy absorbed or released by a substance during a phase change (e.g., vaporisation, fusion, or sublimation) at a constant temperature. This energy is "hidden" because it goes into changing the bonding state of the molecules, rather than increasing their kinetic energy, so the temperature of the substance does not change. This energy is fundamentally the macroscopic manifestation of breaking or forming intermolecular bonds.

To illustrate the magnitude of energy involved, consider the difference in scalding severity between $1\,\text{g}$ of $100\,^\circ\text{C}$ water and $1\,\text{g}$ of $100\,^\circ\text{C}$ steam when they contact skin at approximately $35\,^\circ\text{C}$. For $1\,\text{g}$ of water, the sensible heat released as it cools to $35\,^\circ\text{C}$ is approximately $272\,\text{J}$. In contrast, for $1\,\text{g}$ of steam, two energy components are released: first, the latent heat of condensation as the steam turns into liquid water (approximately $2268\,\text{J}$), and then the sensible heat as that newly condensed water cools to $35\,^\circ\text{C}$ (another $272\,\text{J}$). Therefore, steam transfers roughly an order of magnitude more energy to the skin primarily due to the significant release of latent heat during condensation.

### 5) From macroscopic L_v to microscopic $\varepsilon$: counting neighbours

In condensed phases, the Lennard-Jones attractive potential decays rapidly (as $r^{-6}$), meaning that interactions with nearest neighbours dominate the total energy sum. This allows for a simplification where only the number of nearest neighbours is considered. Typical coordination numbers ($n$) are approximately $n \approx 10$ for liquids (representing an average) and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids. When linking macroscopic latent heat to microscopic bond energy, it is crucial to include a factor of $\frac{1}{2}$ to avoid double counting, as each interatomic bond is shared between two atoms.

The latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, for one mole of a substance, can thus be related to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ by the formula:

$$ L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon $$

Rearranging this equation allows for the calculation of the microscopic bond strength from macroscopic data:

$$ \varepsilon = \frac{2 L_v}{N_A n} $$

For example, for Neon, with a latent heat of vaporisation $L_v = 1.75\,\text{kJ mol}^{-1}$ and assuming $n \approx 10$ (as it is a liquid at its boiling point), the calculated separation energy $\varepsilon$ is approximately $0.004\,\text{eV}$ per bond. This value quantitatively illustrates that van der Waals bonds are indeed thousands of times weaker than typical covalent or ionic bonds, which are on the order of several electron volts.

> **⚠️ Exam Alert!** The lecturer explicitly stated: "And in a solid, that number is 12. So those numbers, and there are a few numbers I expect you remember for this course, and that's one of them." Students are expected to remember the typical nearest neighbour counts: $n \approx 10$ for liquids and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.

### 6) Consolidation: what the parameters tell you physically

The various parameters used in the interatomic force and potential models each carry distinct physical meanings crucial for understanding material properties. The equilibrium separation $a_0$ denotes the distance at which the net interatomic force is zero and the potential energy is at its minimum. The parameter $a$, found in the standard Lennard-Jones potential form, represents the distance at which the potential energy $V(r)$ is zero, serving as an effective atomic diameter or size parameter in the model. The separation energy $\varepsilon$ quantifies the depth of the potential well, representing the energy required to break a single bond or separate a pair of atoms. The effective spring constant $k$ describes the curvature of the potential at its minimum, indicating the stiffness of the interatomic "bond spring." These parameters help to reinforce the vast difference in bond strengths: van der Waals bonds are typically in the range of $10^{-3}$ to $10^{-2}\,\text{eV}$, whereas stronger bonds like ionic, covalent, and metallic bonds are on the order of several electron volts.

## Appendix: Ionic bonding extra (Born-Landé outline)

*Side Note:* This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

This appendix outlines the derivation of the Born-Landé equation for ionic solids. It involves calculating the electrostatic lattice sum, which introduces the Madelung constant $\alpha$ (e.g., approximately $1.75$ for an NaCl structure), and modelling short-range repulsion with a power law term, $A/r^p$. By setting the derivative of the potential to zero at equilibrium, the Born-Landé lattice energy formula can be derived.

## Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

Slides detailing other bonding types such as ionic, covalent (Morse potential), and metallic bonding were present in the lecture slides but were not covered during this session and will be discussed in future lectures.

## Key takeaways

Near equilibrium, interatomic forces can be linearly approximated, causing atoms to behave like masses on springs with an effective spring constant $k = \frac{A(m-n)}{a_0^{m+1}}$. Integrating the two-term force model yields the Lennard-Jones potential, where $\varepsilon$ is the bond strength (well depth), $a$ is the zero-potential distance (a size parameter), and $a_0$ is the equilibrium separation. Van der Waals forces, though weak per pair, explain phenomena like noble gas liquefaction and gecko adhesion through the cumulative effect of many weak bonds. Macroscopically, latent heat represents the energy involved in bond breaking or forming during phase changes; the latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, is linked to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ via $L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon$, where $n$ is the number of nearest neighbours. Typical coordination numbers are $n \approx 10$ for liquids and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.