Lecture 3: Interatomic Forces (part 2) - Springs, Potentials, and Linking to Latent Heat

0) Orientation, quick review, and admin

This lecture builds upon the two-term force model and Lennard-Jones picture introduced in the previous session. We'll transition from discussing interatomic forces to understanding potential energy and its macroscopic consequences, particularly latent heat. Today, the focus is on formalising the "atoms-on-springs" model for small oscillations, deriving and utilising the Lennard-Jones potential forms, interpreting the physical meaning of the well depth parameter $\varepsilon$ as bond strength, and finally connecting this microscopic $\varepsilon$ to macroscopic latent heat measurements by considering nearest neighbours.

The two-term force model describes the net force between two atoms as a balance between short-range repulsion and longer-range attraction. This is mathematically represented as $F(r) = A/r^m - B/r^n$. For matter to remain stable and not collapse, the repulsive force must be stronger and act over a shorter range than the attractive force, meaning the exponent $m$ must be greater than $n$. The equilibrium separation $a_0$ is the distance where the net force $F(a_0) = 0$. In our chosen sign convention, if the positive $r$ direction is to the right, an attractive force pulling atoms together will have a negative sign. While attractive mechanisms can vary (ionic, covalent, metallic, van der Waals), this lecture primarily uses van der Waals interactions for quantitative examples.

Lecture slides and handwritten derivations will be posted, and the lecturer's book annotations often contain additional intermediate steps that students may find useful.

Side Note: Any material placed in the appendix of the lecture notes is supplementary and won't be examined, but it can provide interesting additional information.

1) Small oscillations about equilibrium: atoms behave like masses on springs (SHM)

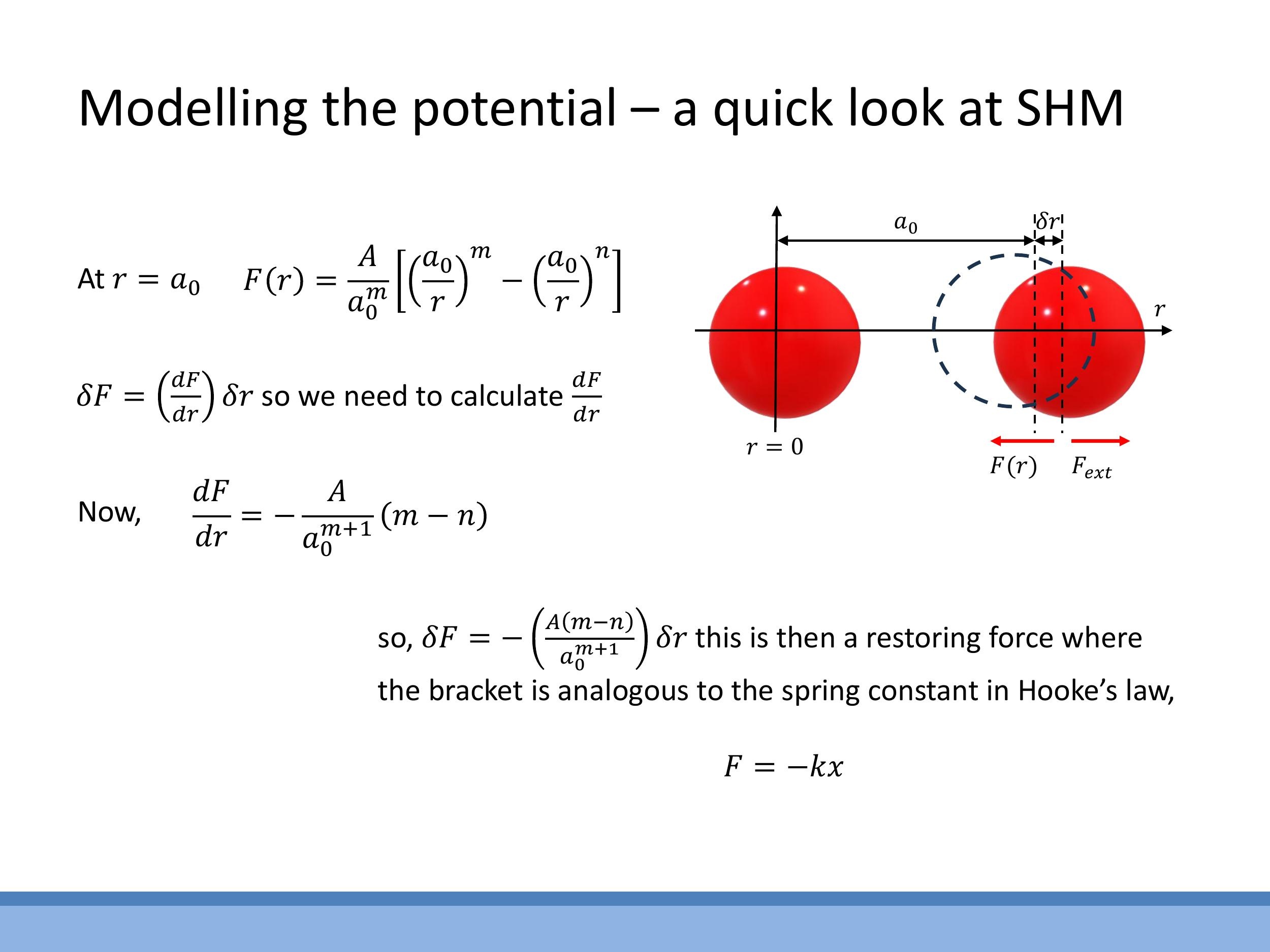

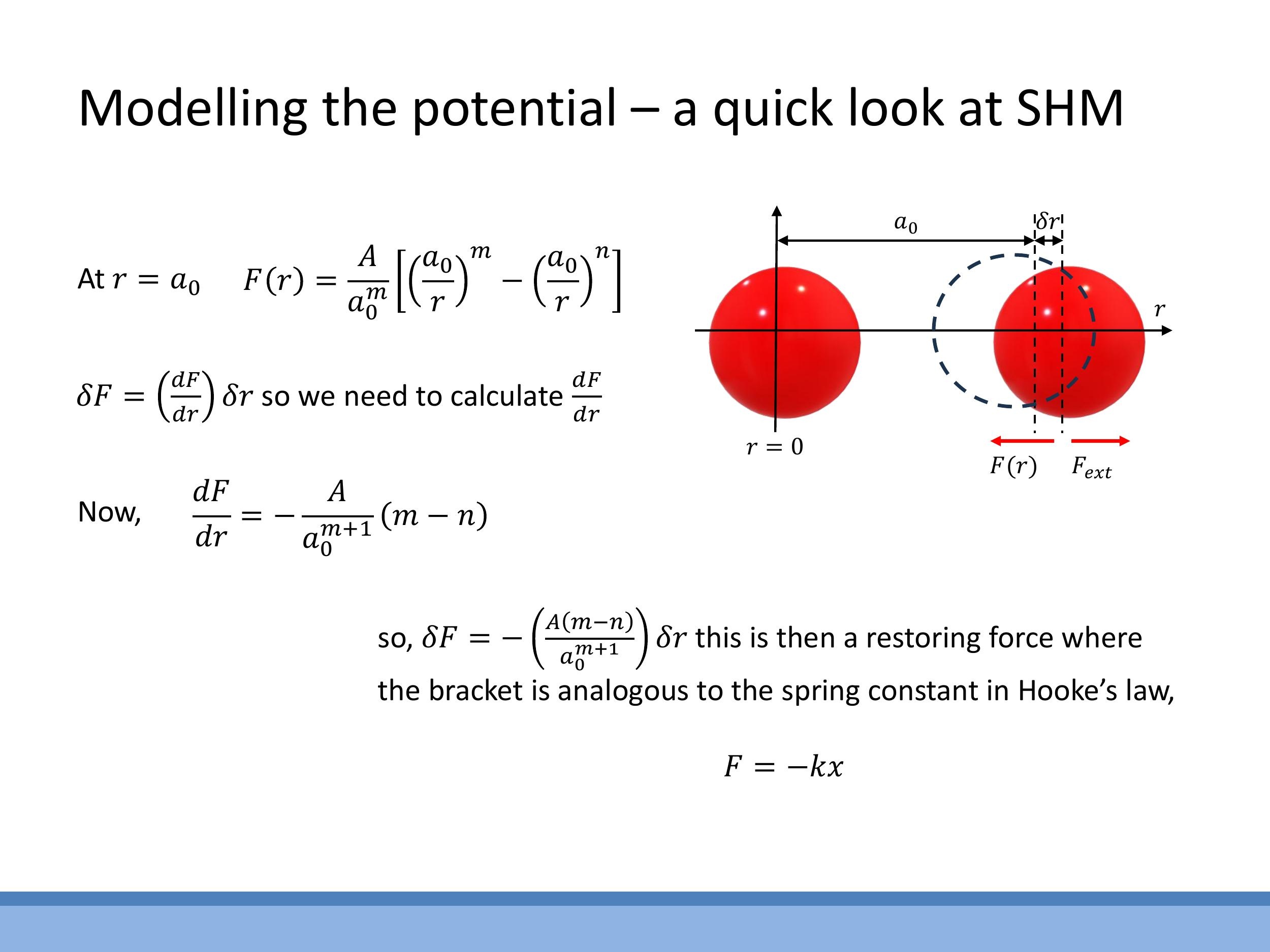

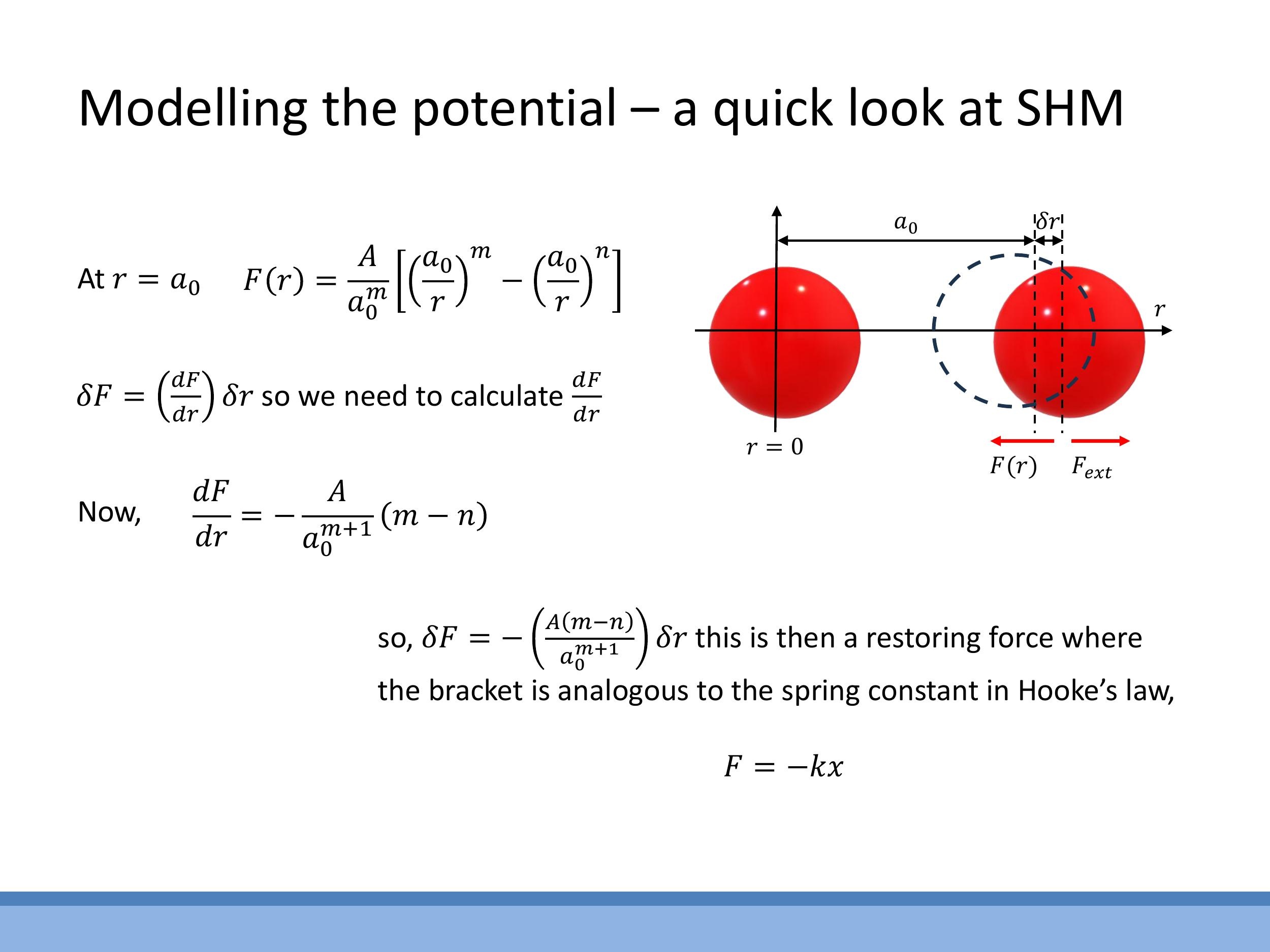

Near the equilibrium separation $a_0$, the interatomic force-distance curve can be approximated as locally linear. This means that small displacements, $\delta r$, away from $a_0$ generate a restoring force that acts to bring the atoms back to their equilibrium position. This behaviour is analogous to a mass attached to a spring, undergoing simple harmonic motion. However, it's crucial to remember that this linear, "spring-like" approximation is only valid for small deviations. Large displacements would lead to non-linear effects, effectively "breaking the spring" as the bond is stretched or compressed beyond its elastic limit, leading to anharmonicity or bond breaking. A physical demonstration using magnets in class helps to illustrate this stable equilibrium point, where strong short-range repulsion balances longer-range attraction, creating a "sweet spot" separation.

To quantify this spring-like behaviour, we can linearise the force around $a_0$. The change in force $\delta F$ for a small displacement $\delta r$ can be approximated by the gradient of the force curve at equilibrium: $\delta F \approx \left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right)\Big| {r=a_0} \cdot \delta r$. This expression directly relates to Hooke's Law, $F = -k \delta r$, where the effective spring constant $k$ is defined as $k \equiv -\left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right)\Big| {a_0} $. Using the two-term force model $ F(r) = \frac{A}{a_0^m}\left[\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^m - \left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^n\right] $, we differentiate with respect to $ r $ and evaluate at $ r=a_0$. This calculation yields:

$$

\left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right)\Big|_{a_0} = -\frac{A(m - n)}{a_0^{m+1}}

$$

Therefore, the effective spring constant $k$ for the interatomic bond is:

$$

k = \frac{A(m - n)}{a_0^{m+1}}

$$

Physically, this shows that the "stiffness" of the bond, represented by $k$, depends on the magnitude of the interaction strength $A$ and the exponents $m$ and $n$ that characterise the range and steepness of the repulsive and attractive forces. A larger value of $k$ indicates a stiffer bond.

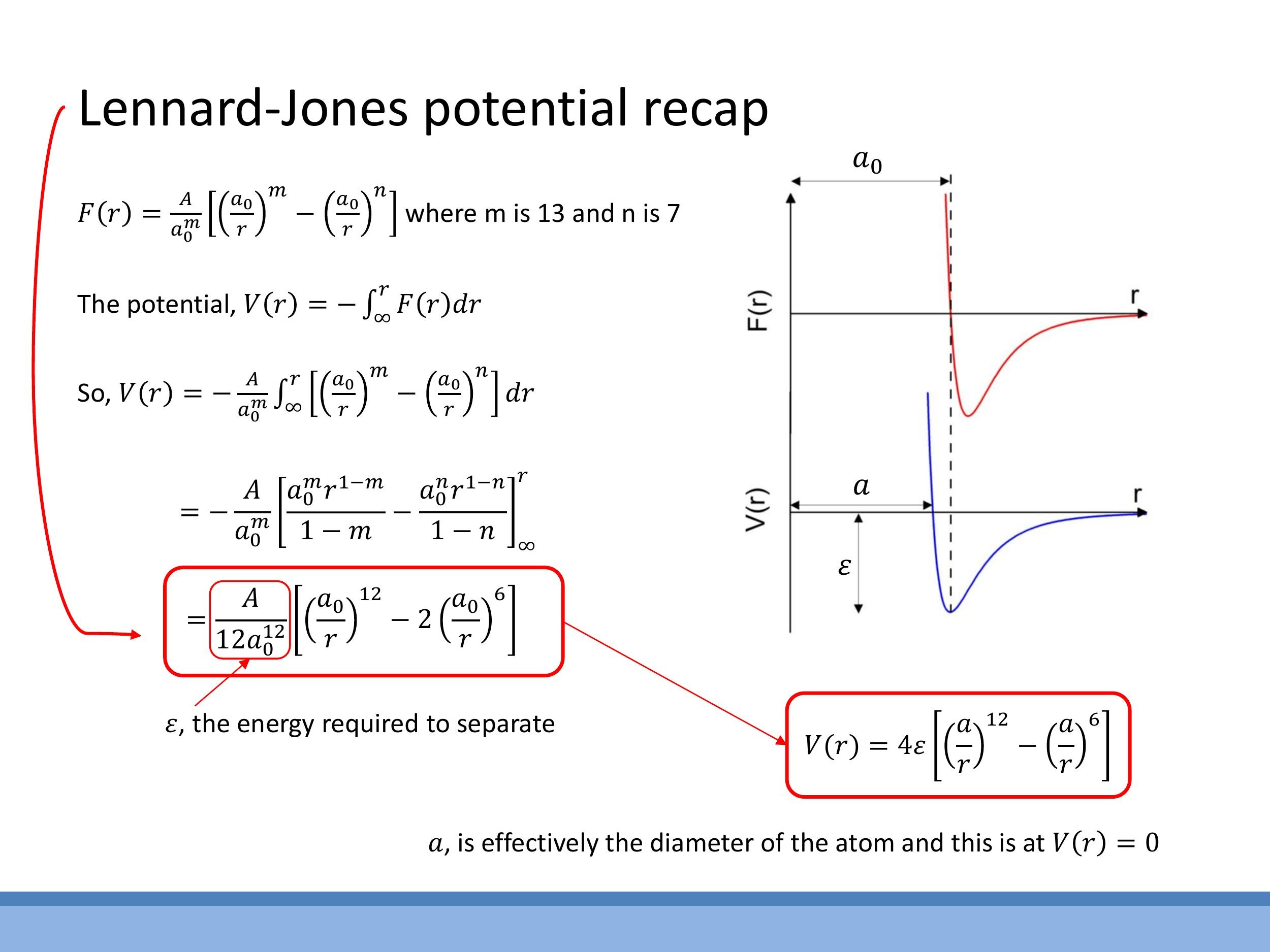

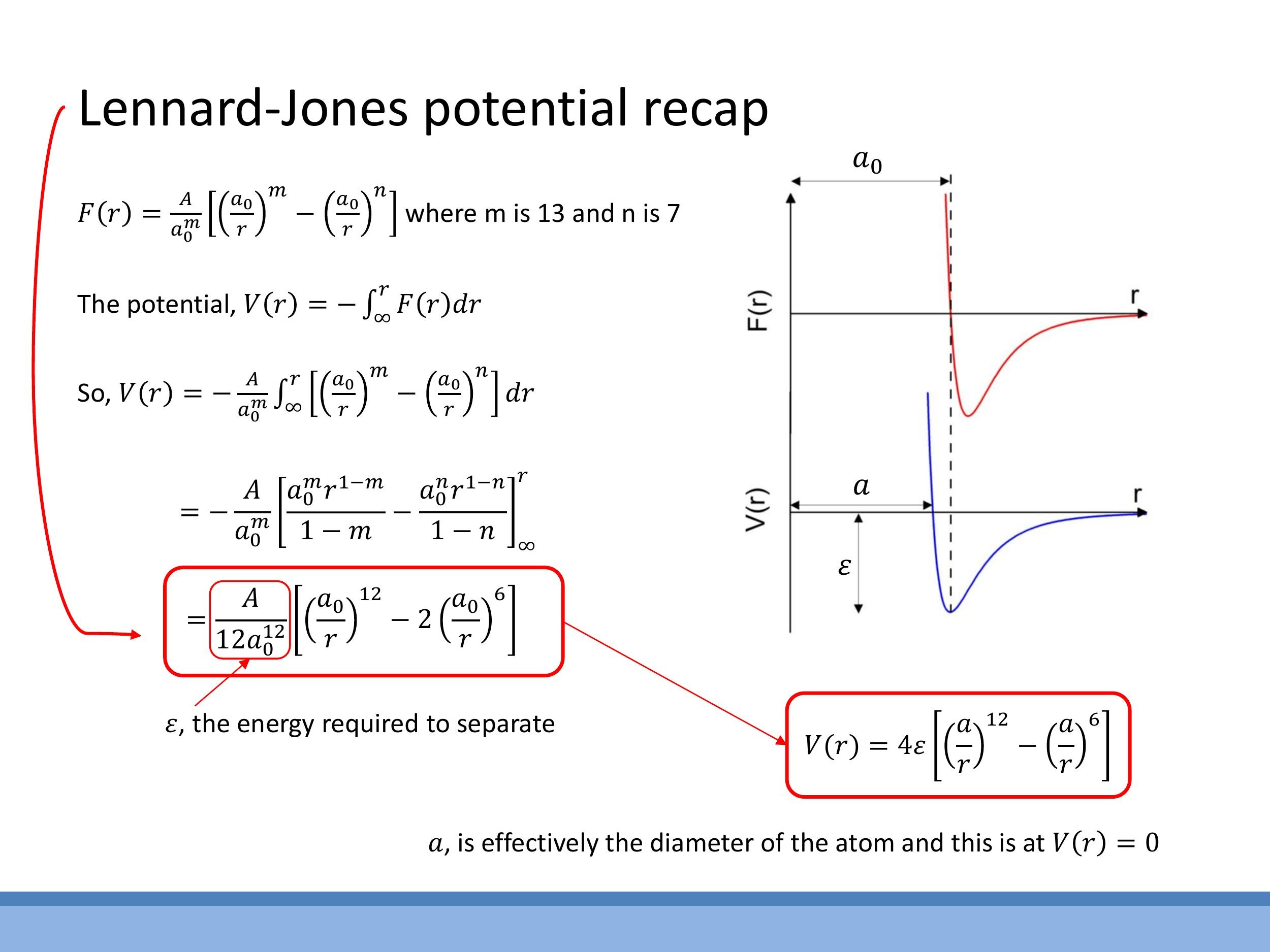

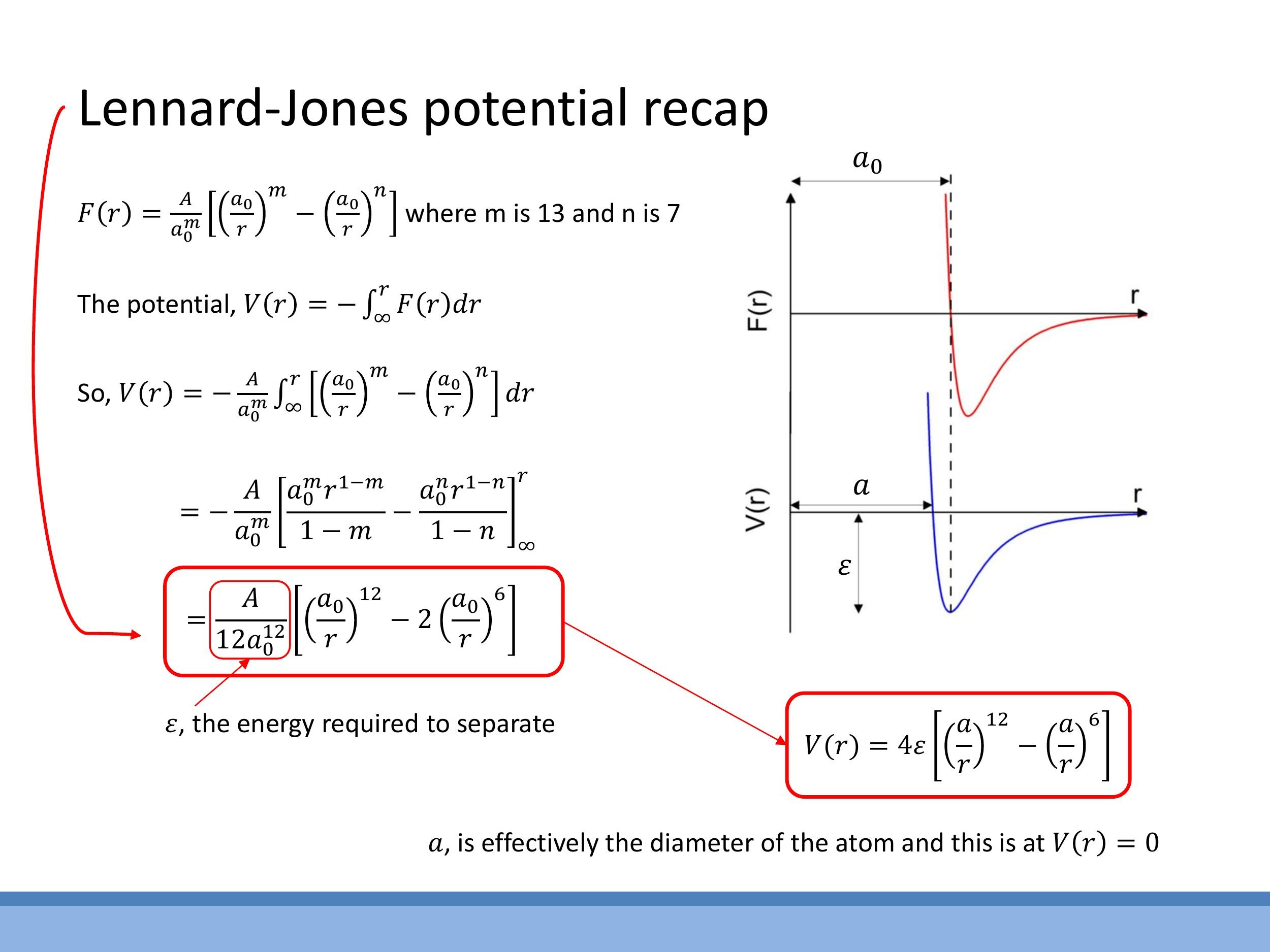

2) From force to potential: the Lennard-Jones well and the meaning of $\varepsilon$ and $a$

While the equilibrium separation $a_0$ is defined as the point where the net force $F(r)$ is zero, it is often more intuitive to describe bond strength and stability using the potential energy, $V(r)$. At $a_0$, the potential energy curve $V(r)$ exhibits a minimum, forming a "potential well." The depth of this well is a crucial parameter, denoted by $\varepsilon$, which represents the separation energy or binding energy required to completely separate the two bonded atoms to an infinite distance. In essence, $\varepsilon$ quantifies the strength of the bond.

To obtain the potential energy $V(r)$ from the force $F(r)$, we integrate the force with respect to distance. By convention, we define $V(\infty) = 0$. Thus, the potential energy at a distance $r$ is given by $V(r) = -\int_r^\infty F(r) dr$. Using the two-term force model with the typical van der Waals exponents $m=13$ and $n=7$, the integration yields a form of the Lennard-Jones potential:

$$

V(r) = \frac{A}{12 a_0^2}\left[\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^6\right]

$$

This can be re-expressed in a more standard textbook form using the parameters $\varepsilon$ and $a$:

$$

V(r) = 4\varepsilon\left[\left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^6\right]

$$

Here, $\varepsilon$ is the well depth, directly representing the bond strength per pair of atoms. The parameter $a$ is a convenient distance at which the potential $V(r)$ passes through zero, making it a useful "size parameter" often considered an effective atomic diameter in a hard-sphere model. It's important to distinguish $a$ from $a_0$, the equilibrium separation where the potential is at its minimum. The relationship between these two parameters is $a_0 = 2^{1/6} a$. These parameters allow us to connect the algebraic form of the potential to its graphical representation: the steep repulsive wall at short distances, the long attractive tail, the zero-crossing at $a$, the minimum at $a_0$, and the well depth $\varepsilon$.

3) Where van der Waals really matters: data and a real-world mechanism

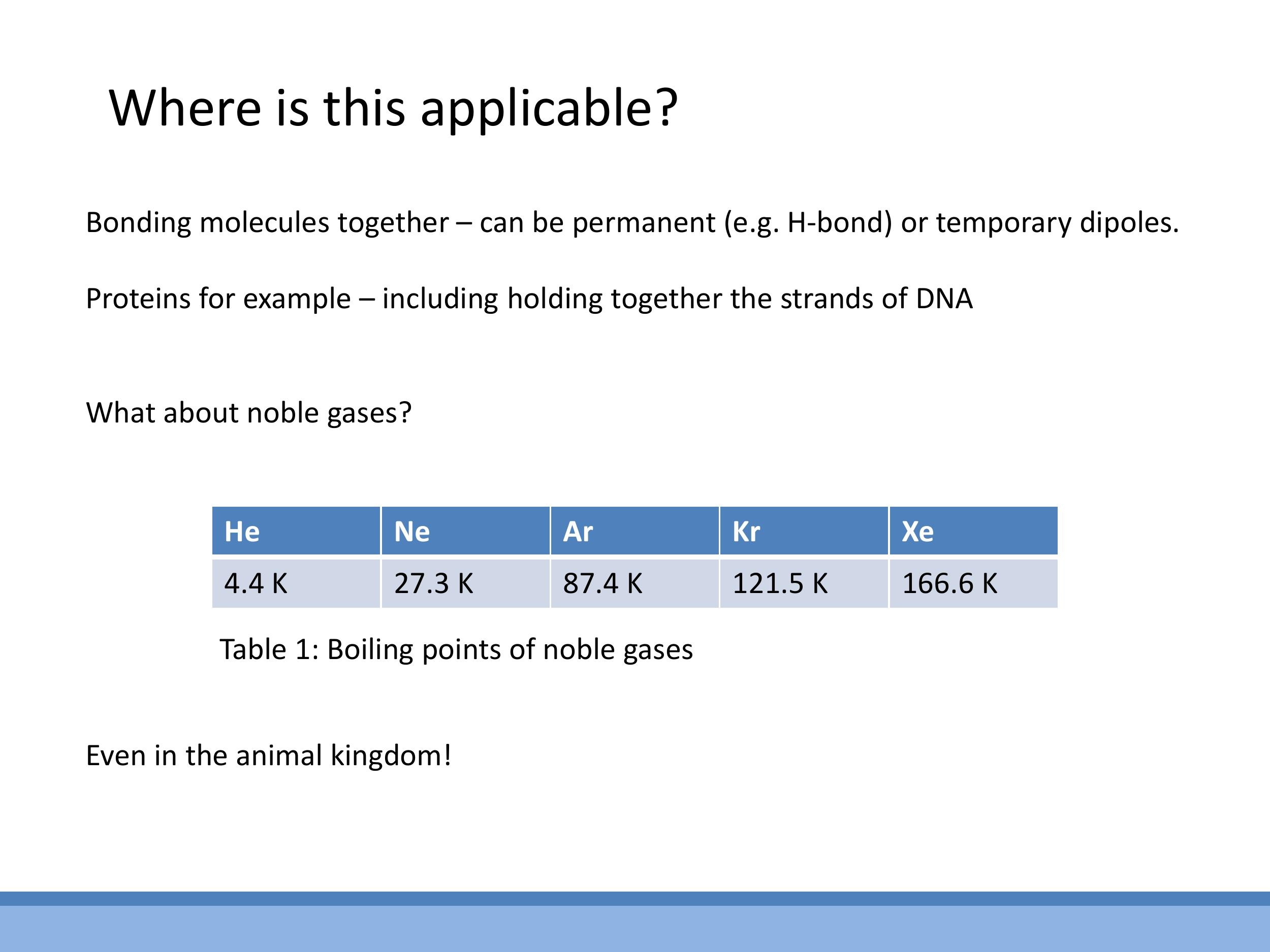

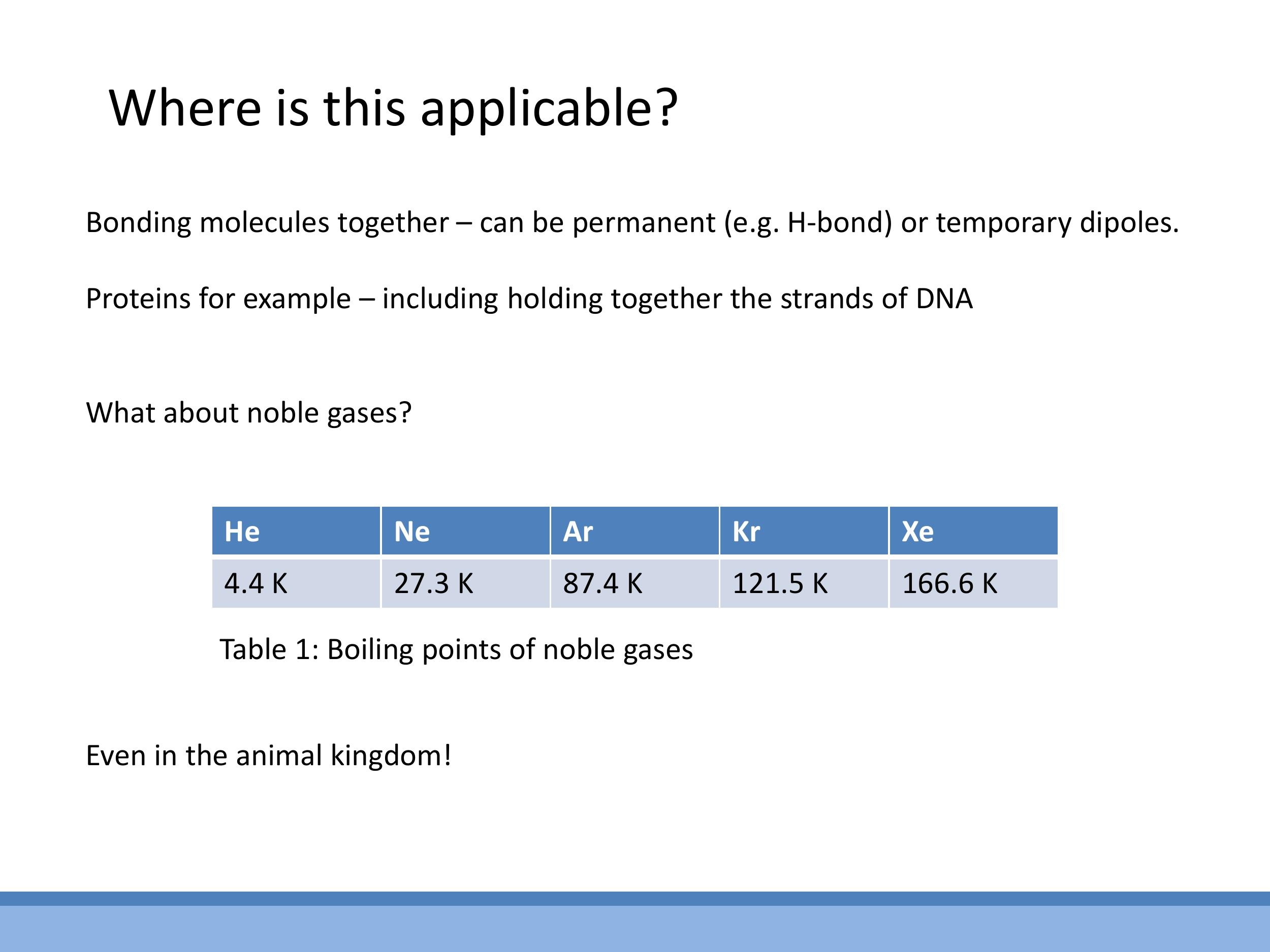

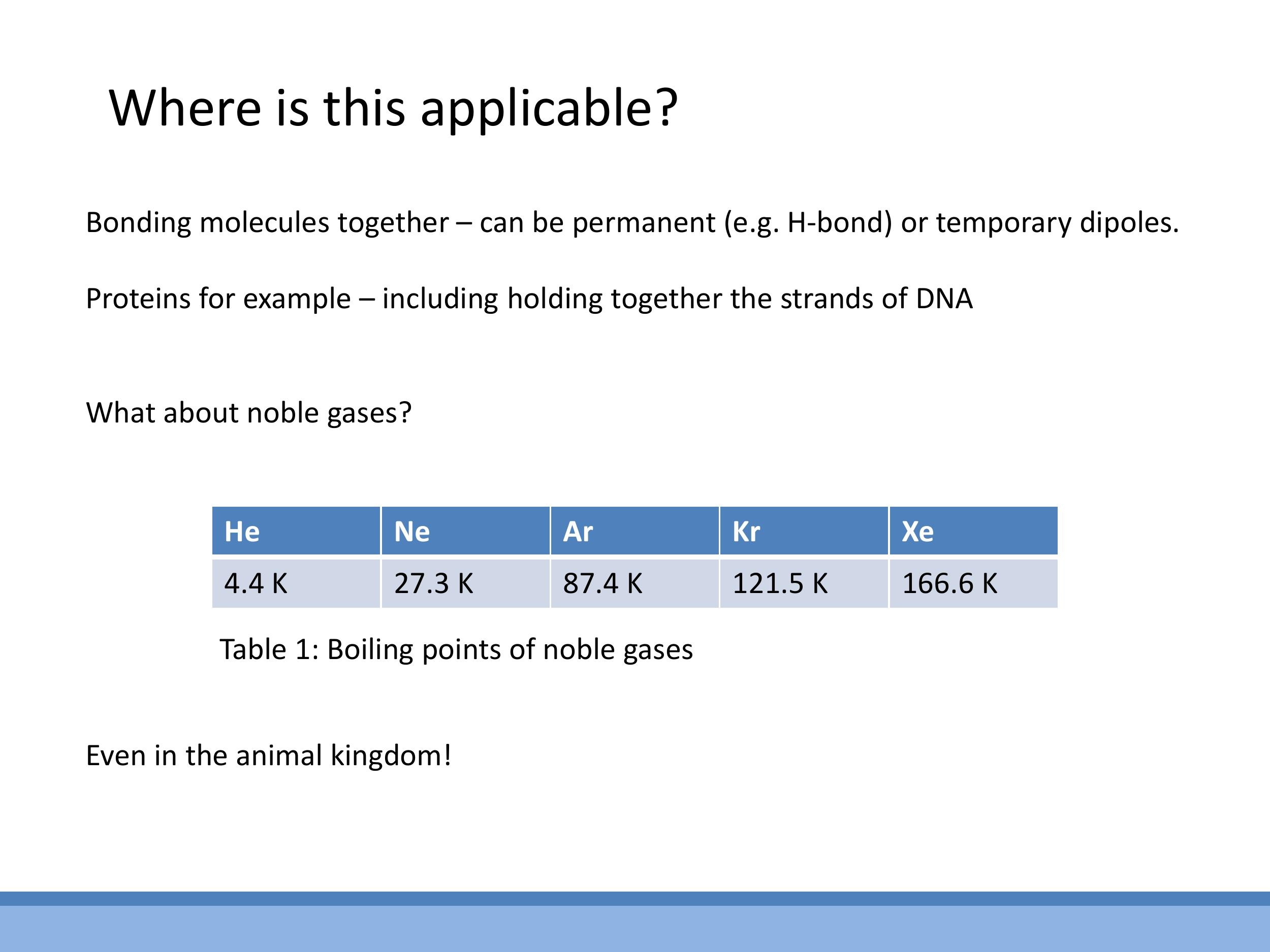

3.1 Liquefaction of noble gases: polarisability and boiling points

A key piece of evidence for the significance of van der Waals forces comes from the liquefaction of noble gases. These elements, such as Helium, Neon, and Argon, possess closed electron shells and are electrically neutral, making them chemically inert. The puzzle is: what attractive force allows them to condense into a liquid state? The answer lies in London dispersion forces, a type of van der Waals interaction. This mechanism involves fluctuating instantaneous dipoles in one atom's electron cloud, which then induce corresponding dipoles in neighbouring atoms, leading to a weak, transient attraction.

This mechanism also explains the observed trend in their boiling points. As one moves down the noble gas group from Helium to Xenon, the atoms become larger, and their outer electrons are less tightly bound to the nucleus. This increased atomic size leads to greater polarisability, meaning it's easier to induce a temporary dipole. Stronger polarisability results in stronger van der Waals bonds. Consequently, more energy (and thus a higher temperature) is required to overcome these stronger bonds, leading to an increase in boiling points, as seen in the table: Neon ($27.3 \, \text{K} $), Argon ($ 87.4 \, \text{K} $), Krypton ($ 121.5 \, \text{K} $), and Xenon ($ 166.6 \, \text{K}$).

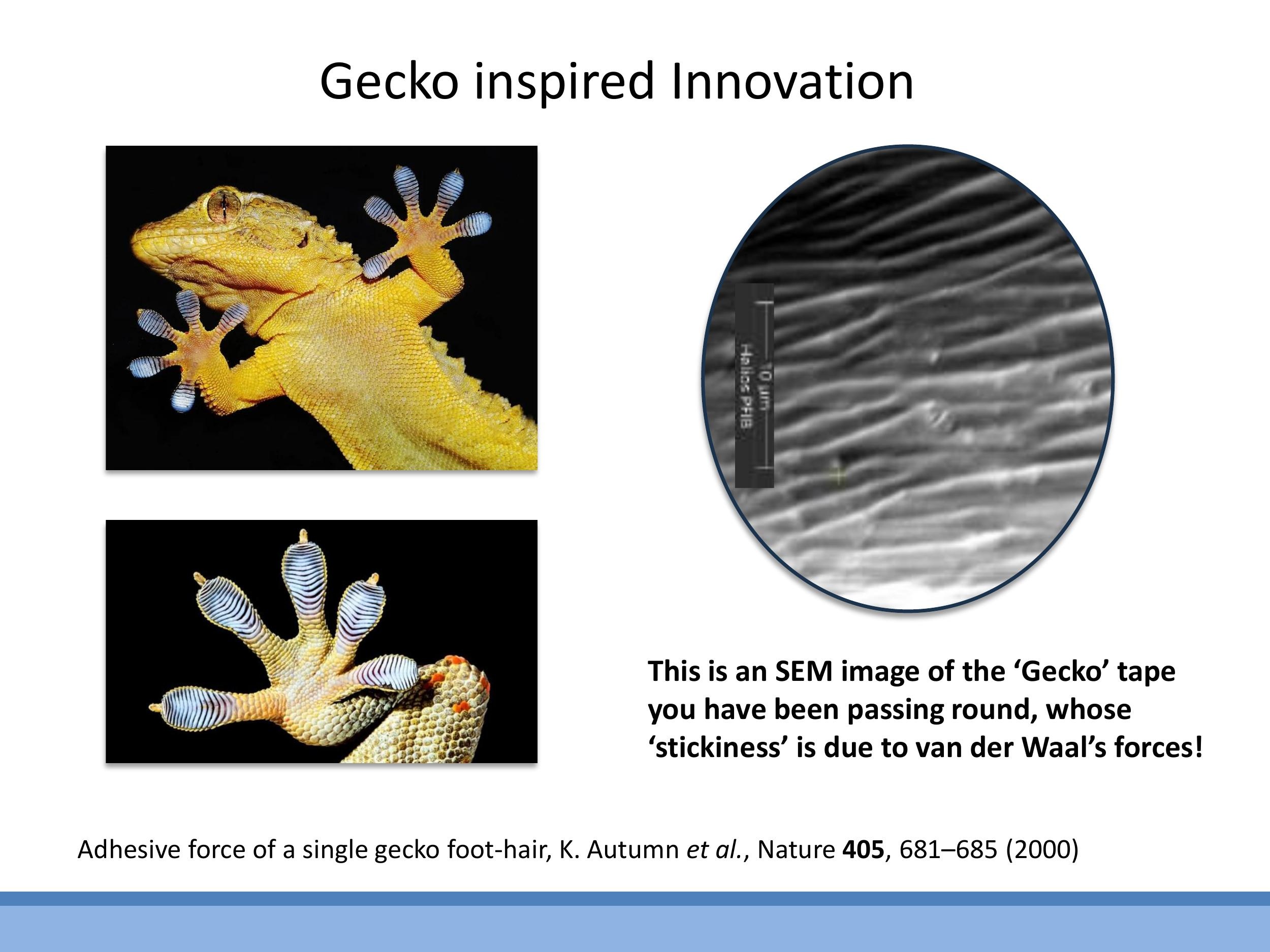

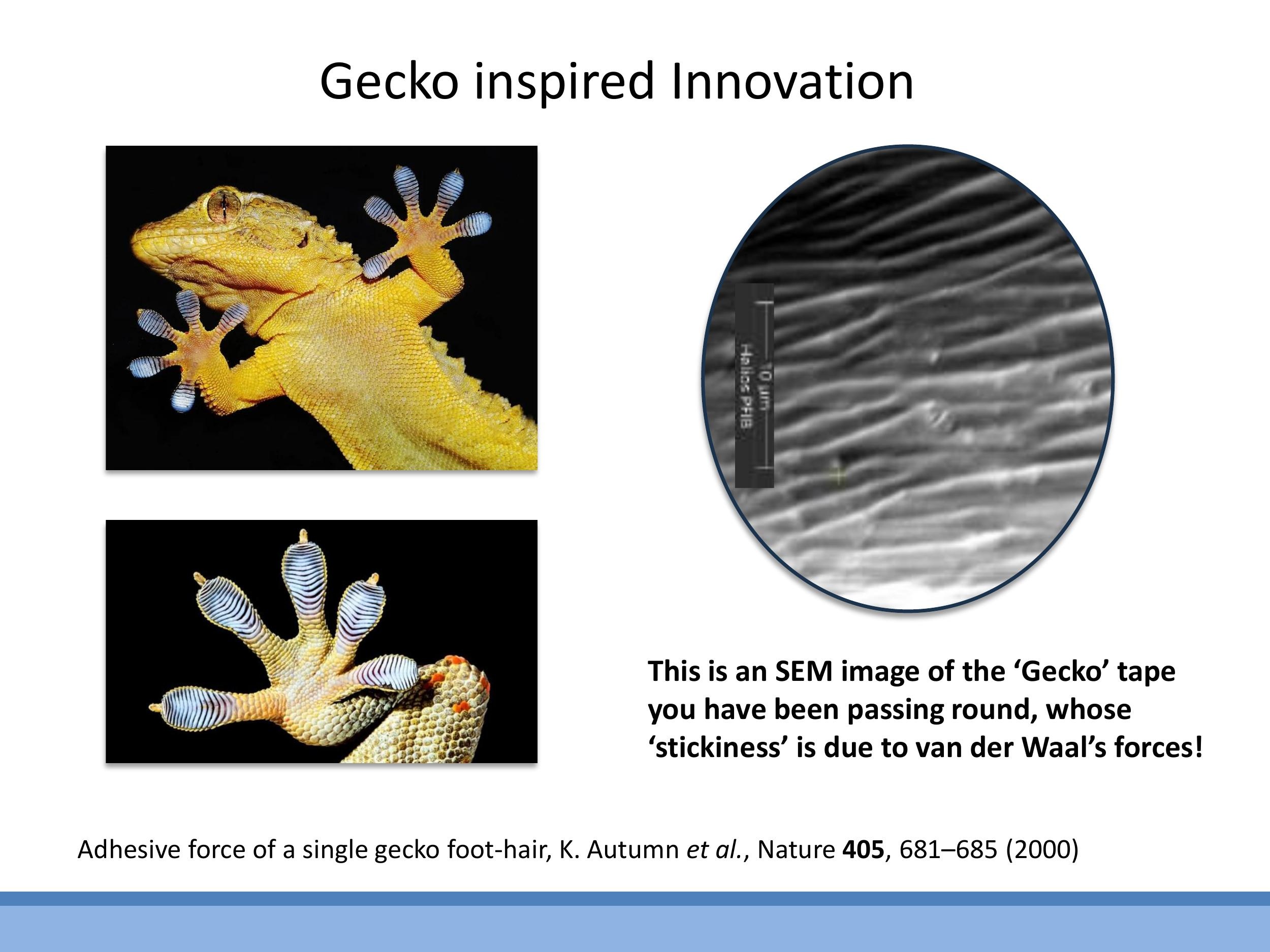

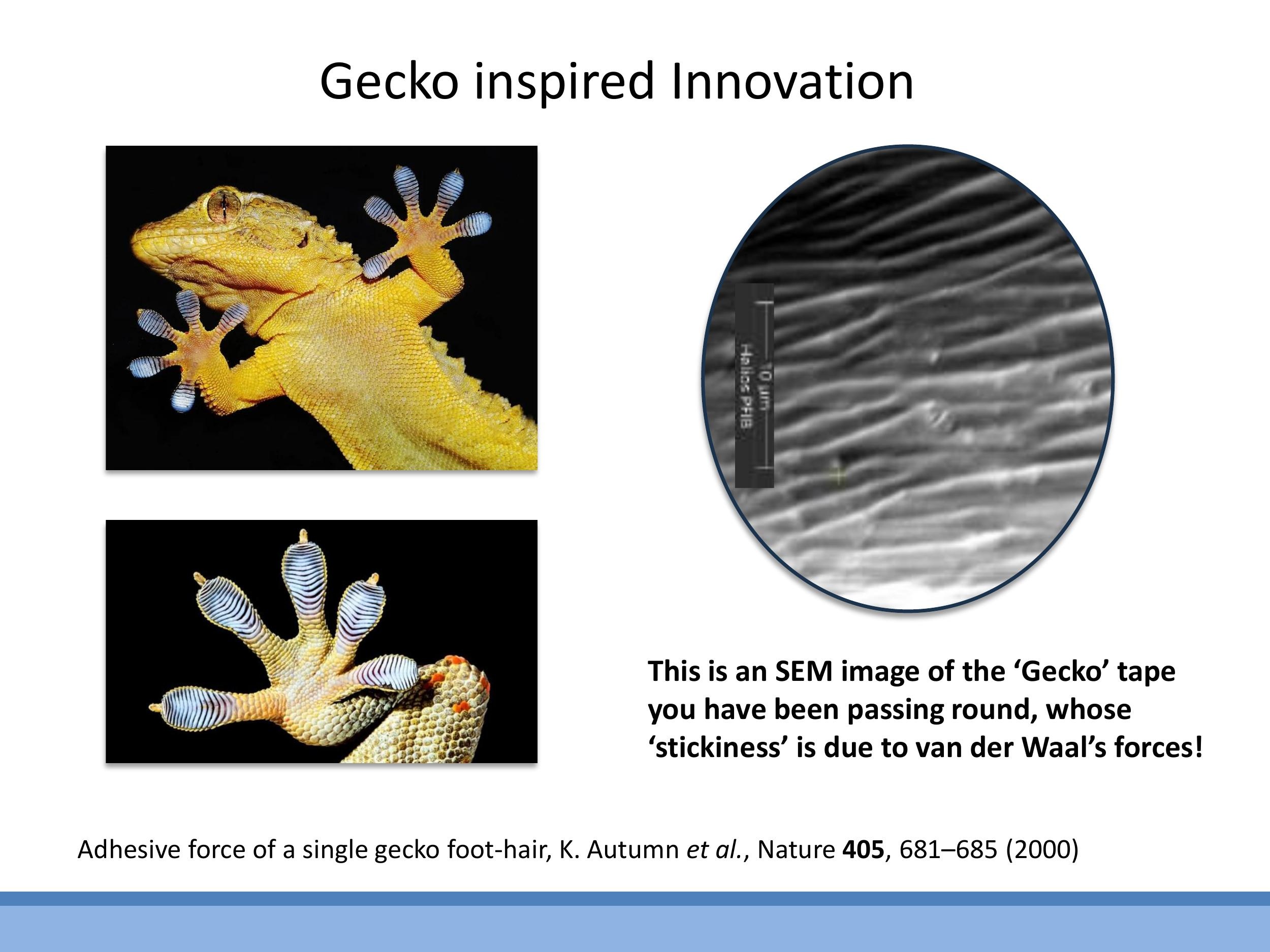

3.2 Gecko adhesion: many tiny weak bonds add up

Another remarkable real-world example of van der Waals forces in action is gecko adhesion. Geckos can cling to and walk across smooth surfaces, even upside down, not through suction or glue, but through the collective effect of millions of tiny van der Waals contacts. Their feet are covered in an enormous surface area of microscopic hair-like structures called setae, which branch into even finer nanoscale fibrils. Each individual contact forms a very weak van der Waals bond with the surface, but the sheer number of these contacts creates a cumulative force strong enough to support the gecko's entire body weight. This principle has been mimicked to create "Gecko tape," a synthetic adhesive that uses high-surface-area microstructures to achieve impressive stickiness without traditional glues.

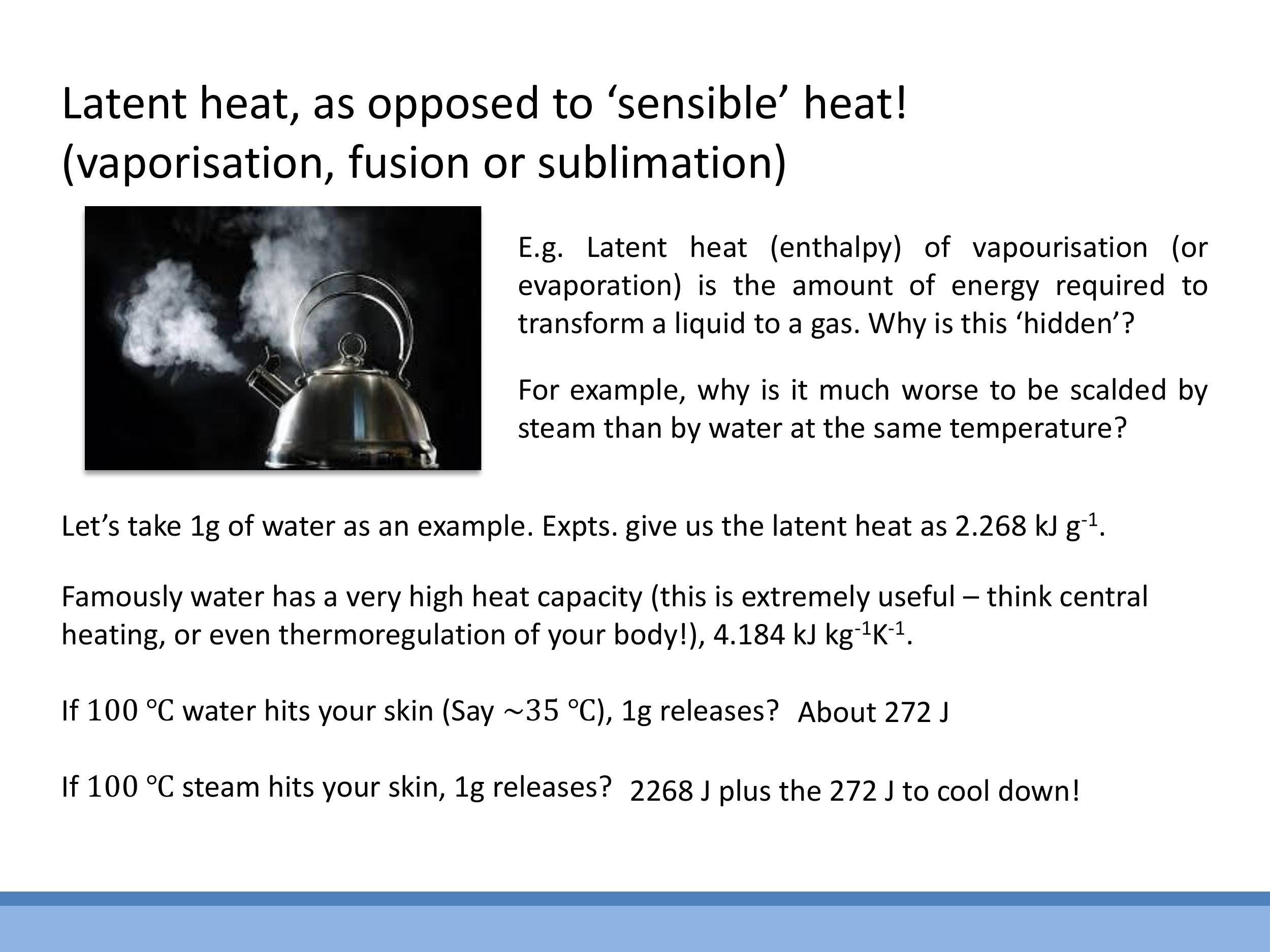

4) Latent heat: the “hidden” energy of bond breaking/forming

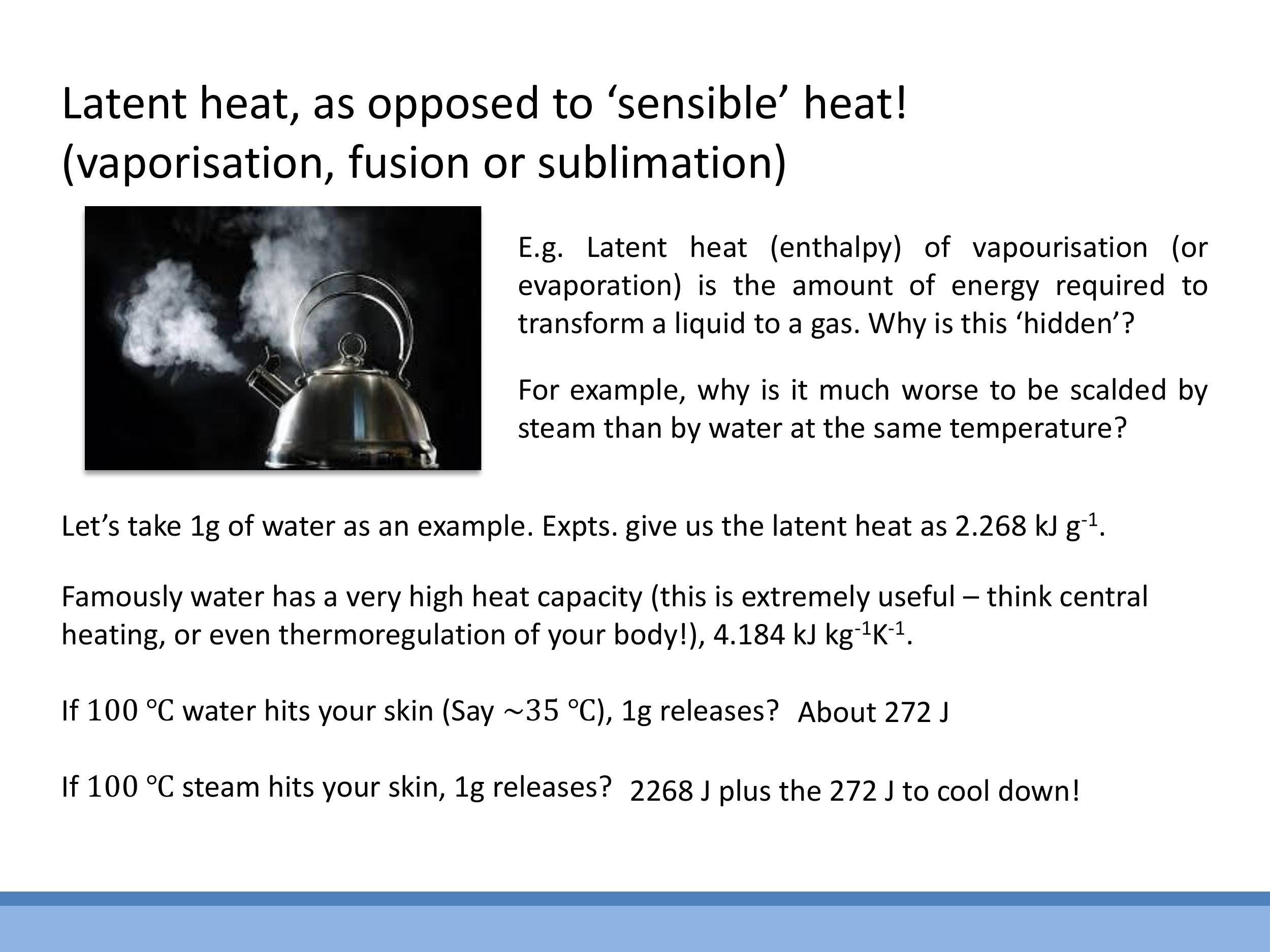

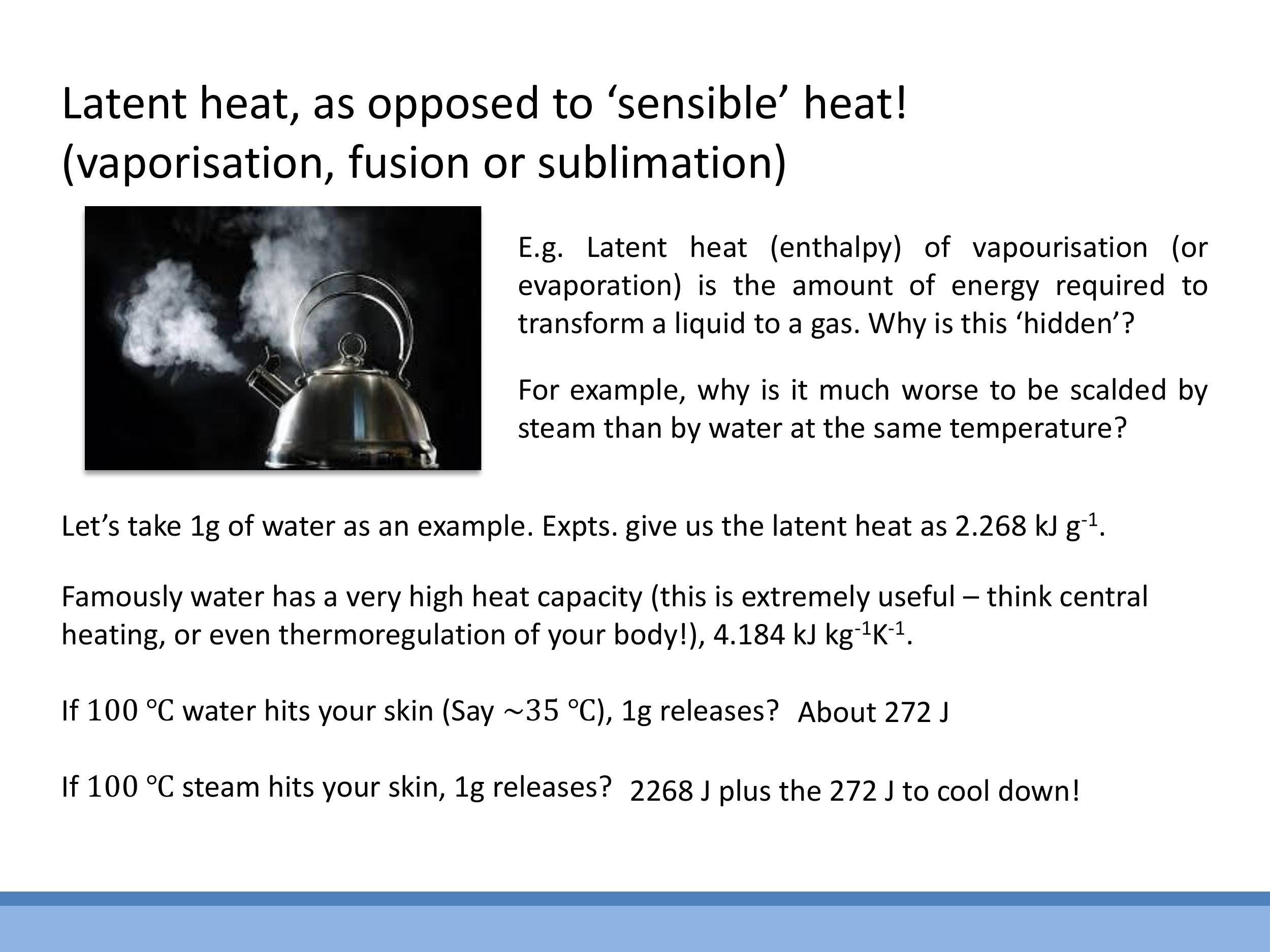

Latent heat is the energy absorbed or released by a substance during a phase change (such as vaporisation, fusion, or sublimation) at a constant temperature. This energy is "hidden" because it goes into changing the bonding state of the molecules rather than increasing their kinetic energy, which would result in a temperature rise. For example, the latent heat of vaporisation is the energy required to break the intermolecular bonds in a liquid so that it can transform into a gas.

To illustrate the significant amount of energy involved in latent heat, consider the difference between a scald from $1 \, \text{g} $ of $ 100 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ water versus $ 1 \, \text{g} $ of $ 100 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ steam when it contacts skin at approximately $ 35 \, ^\circ\text{C} $. For the $ 1 \, \text{g} $ of water, the energy transferred to the skin is primarily "sensible heat" as it cools from $ 100 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ to $ 35 \, ^\circ\text{C} $, which is approximately $ 272 \, \text{J} $. However, for the $ 1 \, \text{g} $ of steam, there are two components of energy transfer. First, the steam must condense into liquid water, releasing its latent heat of condensation, which is about $ 2268 \, \text{J} $. Second, this newly formed liquid water then cools to skin temperature, releasing an additional $ 272 \, \text{J}$. Therefore, the steam transfers roughly an order of magnitude more energy to the skin due to the large amount of latent heat released during condensation. This makes steam scalds significantly more severe.

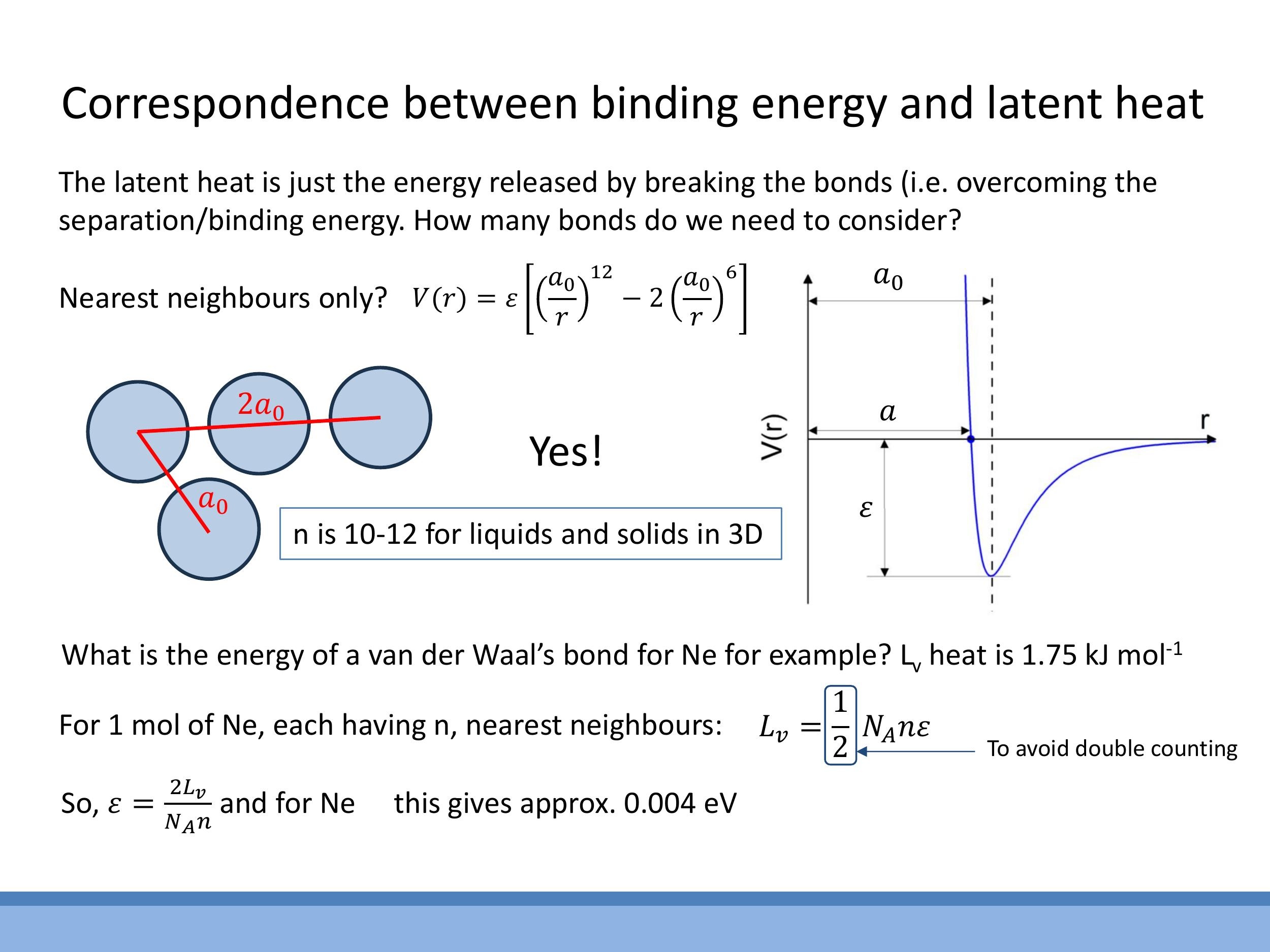

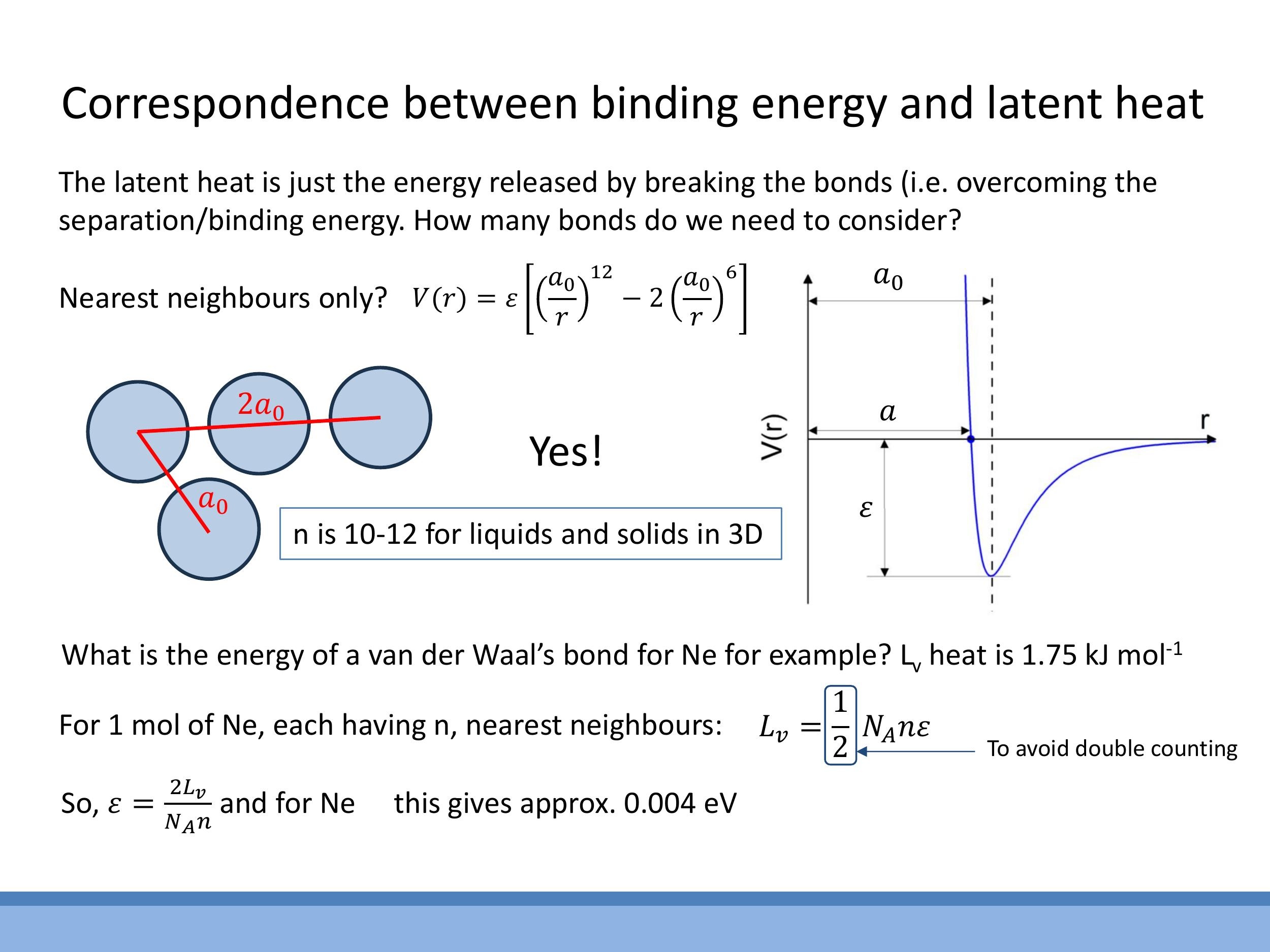

5) From macroscopic L_v to microscopic $\varepsilon$: counting neighbours

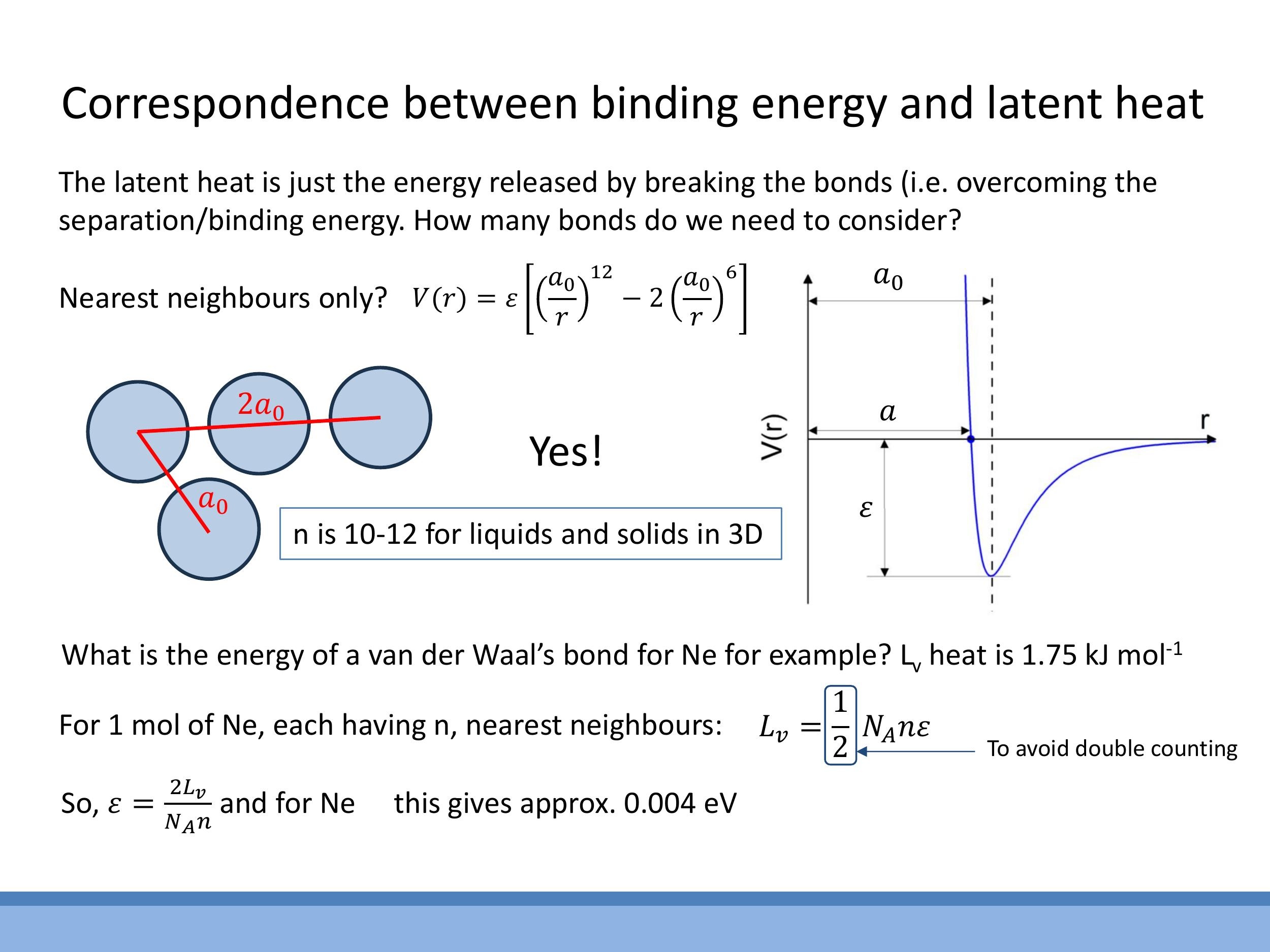

To bridge the gap between macroscopic measurements like latent heat and microscopic bond strength $\varepsilon$, we must consider how atoms interact with multiple neighbours in condensed phases (liquids and solids). The Lennard-Jones attractive potential decays rapidly (as $1/r^6$), meaning that interactions with distant atoms are much weaker and can often be neglected. Therefore, considering only the nearest neighbours is a reasonable approximation for calculating the total bonding energy.

The typical number of nearest neighbours, or coordination number $n$, varies with the phase:

- For liquids, $n$ is approximately $10$ on average, reflecting the less ordered, but still dense, arrangement of atoms.

- For close-packed solids, $n$ is exactly $12$, representing the most efficient way to pack spheres.

⚠️ Exam Alert! The lecturer explicitly stated: "And in a solid, that number is 12. So those numbers, and there are a few numbers I expect you remember for this course, and that's one of them." Students should remember the typical nearest neighbour counts: $n \approx 10$ for liquids and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.

When linking latent heat to per-bond energy, it's crucial to avoid double-counting. Each bond is shared between two atoms, so we include a factor of $1/2$. The latent heat of vaporisation per mole, $L_v$, can then be related to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ by:

$$

L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon

$$

where $N_A$ is Avogadro's number. This equation can be rearranged to find the microscopic separation energy per bond:

$$

\varepsilon = \frac{2 L_v}{N_A n}

$$

Let's apply this to an example like Neon. Given its latent heat of vaporisation $L_v = 1.75 \, \text{kJ mol}^{-1} $, and assuming $ n \approx 10 $ for a liquid, we can calculate $ \varepsilon $. Plugging in the values, we find $ \varepsilon \approx 0.004 \, \text{eV}$ per bond. This result provides a quantitative sense of scale, confirming that van der Waals bonds are indeed very weak, typically thousands of times weaker than the several electron-volt energies associated with strong covalent or ionic bonds.

6) Consolidation: what the parameters tell you physically

To summarise, the parameters we've discussed provide clear physical insights into interatomic interactions:

- $a_0$: This is the equilibrium separation distance between two atoms, where the net interatomic force is zero and the potential energy is at its minimum.

- $a$: In the Lennard-Jones potential, this parameter represents the distance at which the potential energy $V(r)$ crosses zero, serving as a useful effective atomic diameter or size parameter in the model.

- $\varepsilon$: This is the bond or separation energy per pair of atoms, equivalent to the depth of the potential well, and quantifies the energy required to break a single bond.

- $k$: This effective spring constant represents the curvature of the potential energy well at its minimum, indicating the stiffness of the "bond spring" for small oscillations.

It's important to keep the orders of magnitude in mind: van der Waals bonds typically have separation energies $\varepsilon$ in the range of $10^{-3}$ to $10^{-2} \, \text{eV}$, whereas strong bonds like ionic, covalent, or metallic bonds are significantly stronger, on the order of several electron volts.

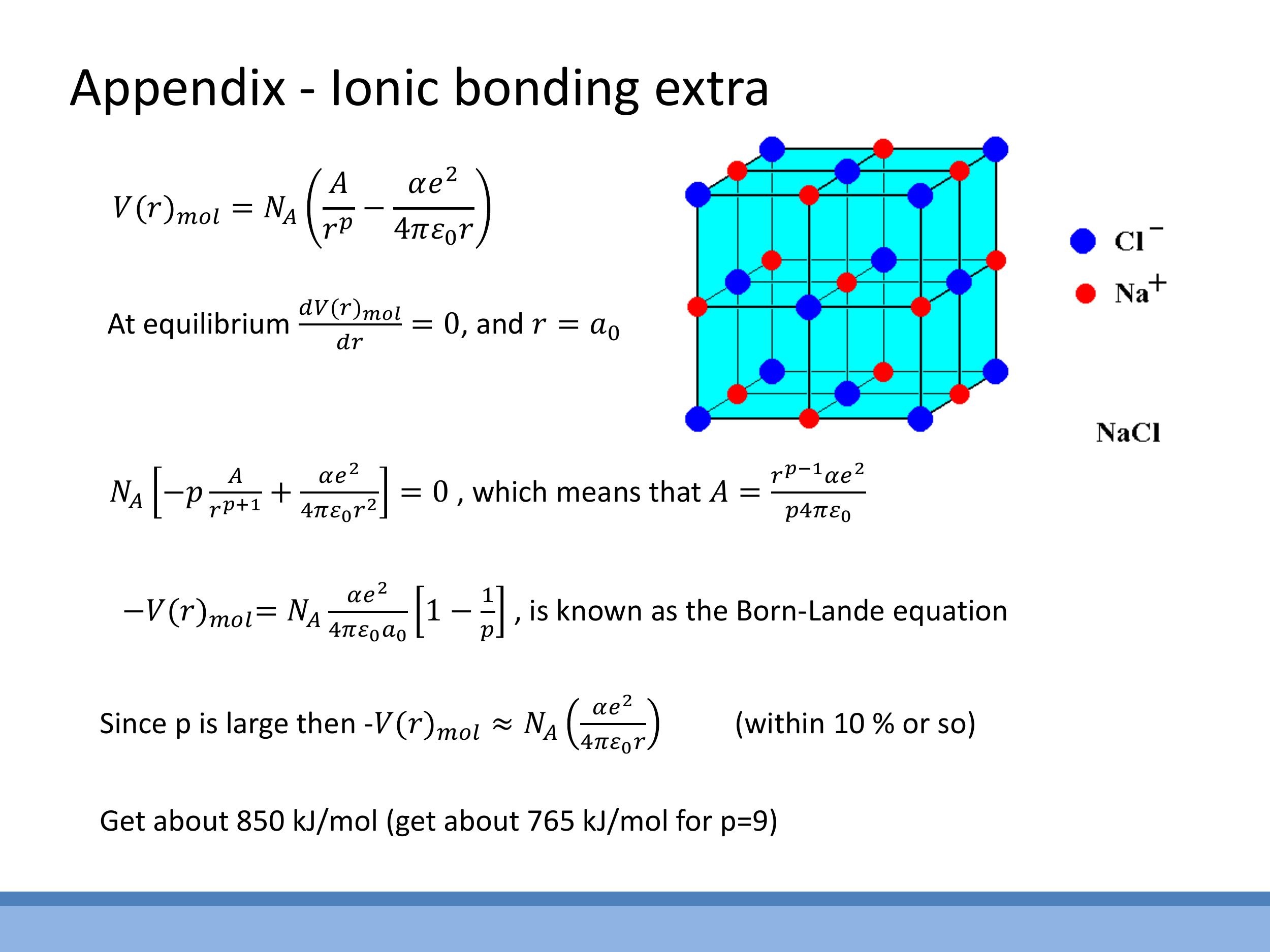

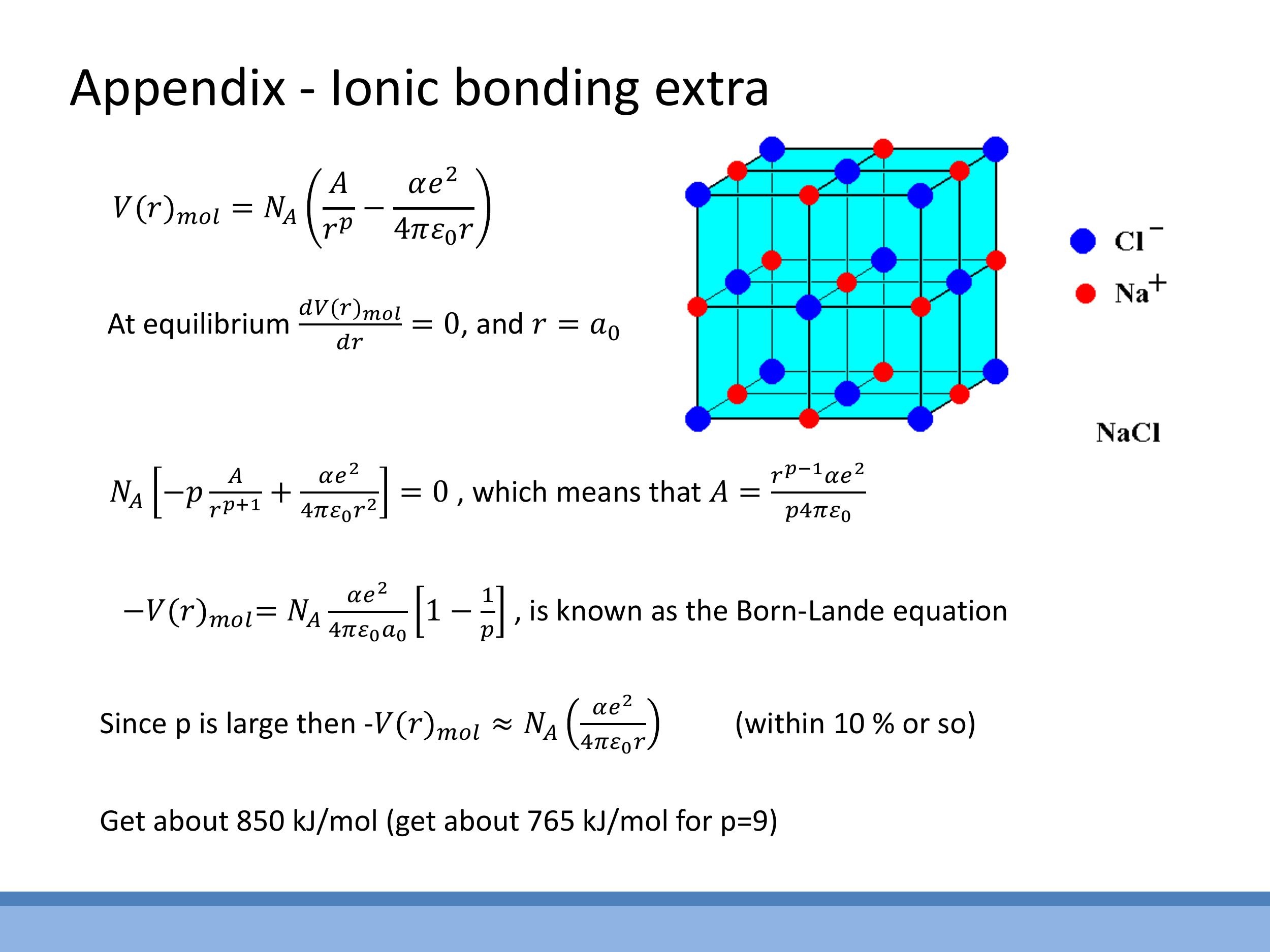

Side Note: This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

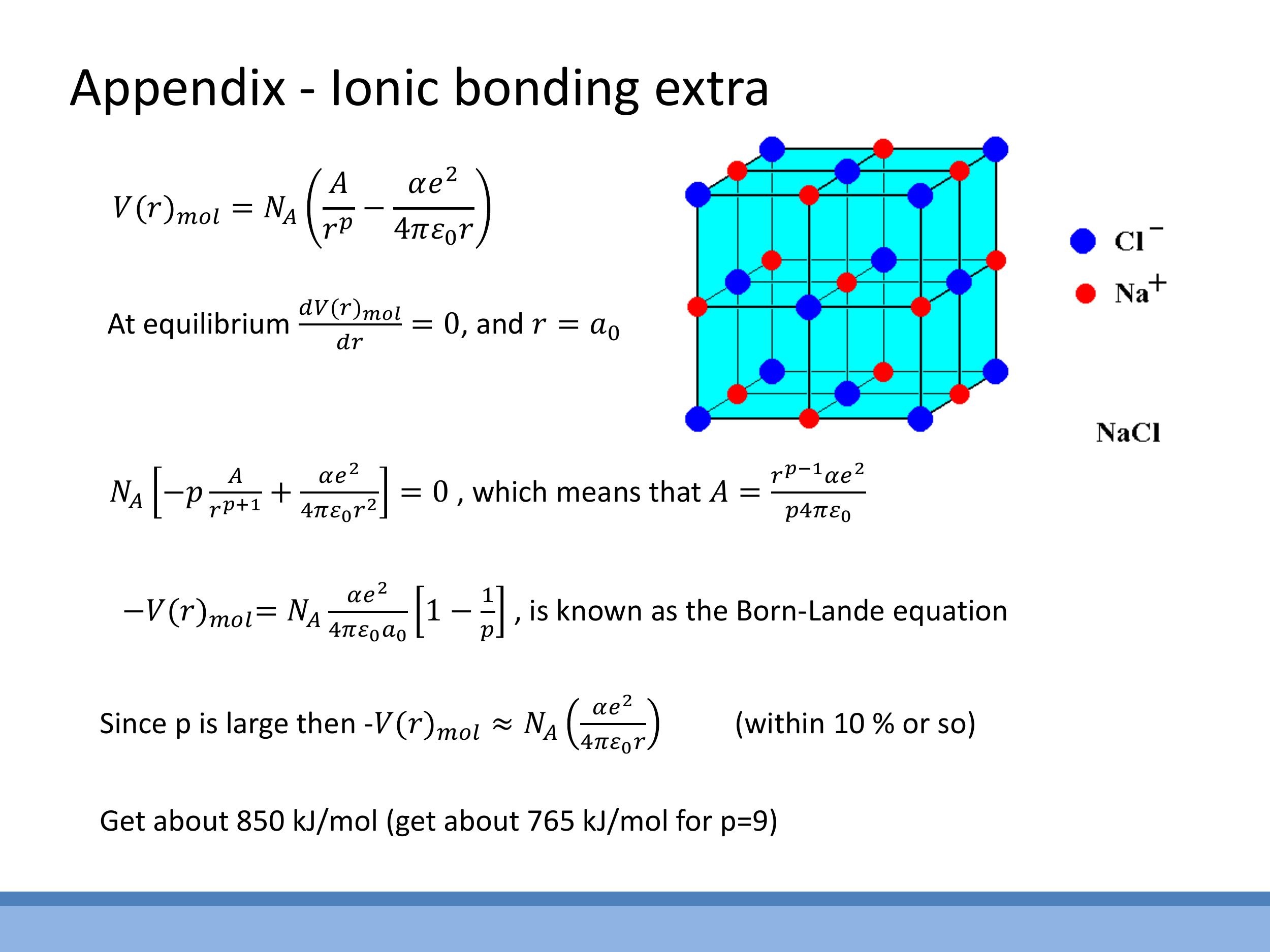

This appendix outlines the more complex calculation for ionic bonding, which involves summing electrostatic interactions across an entire crystal lattice. This leads to the introduction of the Madelung constant, $\alpha$, which accounts for the specific geometric arrangement of ions in a crystal structure (e.g., $\alpha \approx 1.75$ for NaCl). Combining this with a short-range repulsive term, often modelled as $A/r^p$, allows for the derivation of the Born-Landé equation, which provides a theoretical value for the lattice energy of ionic solids.

Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

Slides titled "Now let's consider the other bonding types" and subsequent slides detailing ionic, covalent (Morse potential), and metallic bonding were not covered in this lecture. These topics will be addressed in future sessions.

Key takeaways

Near equilibrium, interatomic forces can be well-approximated by a linear restoring force, meaning atoms behave like masses on springs, with an effective spring constant $k = A(m - n)/a_0^{(m+1)}$. Integrating the two-term force model leads to the Lennard-Jones potential, from which we can directly read $\varepsilon$ (the well depth or bond strength), $a$ (a size parameter where $V=0$), and $a_0$ (the equilibrium separation at the potential minimum). Van der Waals forces, though weak per individual pair, are crucial for phenomena like noble gas liquefaction and gecko adhesion, where millions of tiny contacts sum to a significant collective force. Macroscopically, latent heat is the energy associated with bond breaking or forming during phase changes. This allows us to connect the latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ through a neighbour counting argument, $L_v = (1/2) N_A n \varepsilon$. Typical coordination numbers are $n \approx 10$ for liquids and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.

⚠️ Exam Alert! The lecturer explicitly stated: "And in a solid, that number is 12. So those numbers, and there are a few numbers I expect you remember for this course, and that's one of them." Students should remember that the typical coordination number for a close-packed solid is $n=12$.

## Lecture 3: Interatomic Forces (part 2) - Springs, Potentials, and Linking to Latent Heat

### 0) Orientation, quick review, and admin

This lecture builds upon the two-term force model and Lennard-Jones picture introduced in the previous session. We'll transition from discussing interatomic forces to understanding potential energy and its macroscopic consequences, particularly latent heat. Today, the focus is on formalising the "atoms-on-springs" model for small oscillations, deriving and utilising the Lennard-Jones potential forms, interpreting the physical meaning of the well depth parameter $\varepsilon$ as bond strength, and finally connecting this microscopic $\varepsilon$ to macroscopic latent heat measurements by considering nearest neighbours.

The two-term force model describes the net force between two atoms as a balance between short-range repulsion and longer-range attraction. This is mathematically represented as $F(r) = A/r^m - B/r^n$. For matter to remain stable and not collapse, the repulsive force must be stronger and act over a shorter range than the attractive force, meaning the exponent $m$ must be greater than $n$. The equilibrium separation $a_0$ is the distance where the net force $F(a_0) = 0$. In our chosen sign convention, if the positive $r$ direction is to the right, an attractive force pulling atoms together will have a negative sign. While attractive mechanisms can vary (ionic, covalent, metallic, van der Waals), this lecture primarily uses van der Waals interactions for quantitative examples.

Lecture slides and handwritten derivations will be posted, and the lecturer's book annotations often contain additional intermediate steps that students may find useful.

*Side Note:* Any material placed in the appendix of the lecture notes is supplementary and won't be examined, but it can provide interesting additional information.

### 1) Small oscillations about equilibrium: atoms behave like masses on springs (SHM)

Near the equilibrium separation $a_0$, the interatomic force-distance curve can be approximated as locally linear. This means that small displacements, $\delta r$, away from $a_0$ generate a restoring force that acts to bring the atoms back to their equilibrium position. This behaviour is analogous to a mass attached to a spring, undergoing simple harmonic motion. However, it's crucial to remember that this linear, "spring-like" approximation is only valid for small deviations. Large displacements would lead to non-linear effects, effectively "breaking the spring" as the bond is stretched or compressed beyond its elastic limit, leading to anharmonicity or bond breaking. A physical demonstration using magnets in class helps to illustrate this stable equilibrium point, where strong short-range repulsion balances longer-range attraction, creating a "sweet spot" separation.

To quantify this spring-like behaviour, we can linearise the force around $a_0$. The change in force $\delta F$ for a small displacement $\delta r$ can be approximated by the gradient of the force curve at equilibrium: $\delta F \approx \left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right)\Big|_{r=a_0} \cdot \delta r$. This expression directly relates to Hooke's Law, $F = -k \delta r$, where the effective spring constant $k$ is defined as $k \equiv -\left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right)\Big|_{a_0}$. Using the two-term force model $F(r) = \frac{A}{a_0^m}\left[\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^m - \left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^n\right]$, we differentiate with respect to $r$ and evaluate at $r=a_0$. This calculation yields:

$$\left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right)\Big|_{a_0} = -\frac{A(m - n)}{a_0^{m+1}}$$

Therefore, the effective spring constant $k$ for the interatomic bond is:

$$k = \frac{A(m - n)}{a_0^{m+1}}$$

Physically, this shows that the "stiffness" of the bond, represented by $k$, depends on the magnitude of the interaction strength $A$ and the exponents $m$ and $n$ that characterise the range and steepness of the repulsive and attractive forces. A larger value of $k$ indicates a stiffer bond.

### 2) From force to potential: the Lennard-Jones well and the meaning of $\varepsilon$ and $a$

While the equilibrium separation $a_0$ is defined as the point where the net force $F(r)$ is zero, it is often more intuitive to describe bond strength and stability using the potential energy, $V(r)$. At $a_0$, the potential energy curve $V(r)$ exhibits a minimum, forming a "potential well." The depth of this well is a crucial parameter, denoted by $\varepsilon$, which represents the separation energy or binding energy required to completely separate the two bonded atoms to an infinite distance. In essence, $\varepsilon$ quantifies the strength of the bond.

To obtain the potential energy $V(r)$ from the force $F(r)$, we integrate the force with respect to distance. By convention, we define $V(\infty) = 0$. Thus, the potential energy at a distance $r$ is given by $V(r) = -\int_r^\infty F(r) dr$. Using the two-term force model with the typical van der Waals exponents $m=13$ and $n=7$, the integration yields a form of the Lennard-Jones potential:

$$V(r) = \frac{A}{12 a_0^2}\left[\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{a_0}{r}\right)^6\right]$$

This can be re-expressed in a more standard textbook form using the parameters $\varepsilon$ and $a$:

$$V(r) = 4\varepsilon\left[\left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^6\right]$$

Here, $\varepsilon$ is the well depth, directly representing the bond strength per pair of atoms. The parameter $a$ is a convenient distance at which the potential $V(r)$ passes through zero, making it a useful "size parameter" often considered an effective atomic diameter in a hard-sphere model. It's important to distinguish $a$ from $a_0$, the equilibrium separation where the potential is at its minimum. The relationship between these two parameters is $a_0 = 2^{1/6} a$. These parameters allow us to connect the algebraic form of the potential to its graphical representation: the steep repulsive wall at short distances, the long attractive tail, the zero-crossing at $a$, the minimum at $a_0$, and the well depth $\varepsilon$.

### 3) Where van der Waals really matters: data and a real-world mechanism

#### 3.1 Liquefaction of noble gases: polarisability and boiling points

A key piece of evidence for the significance of van der Waals forces comes from the liquefaction of noble gases. These elements, such as Helium, Neon, and Argon, possess closed electron shells and are electrically neutral, making them chemically inert. The puzzle is: what attractive force allows them to condense into a liquid state? The answer lies in London dispersion forces, a type of van der Waals interaction. This mechanism involves fluctuating instantaneous dipoles in one atom's electron cloud, which then induce corresponding dipoles in neighbouring atoms, leading to a weak, transient attraction.

This mechanism also explains the observed trend in their boiling points. As one moves down the noble gas group from Helium to Xenon, the atoms become larger, and their outer electrons are less tightly bound to the nucleus. This increased atomic size leads to greater polarisability, meaning it's easier to induce a temporary dipole. Stronger polarisability results in stronger van der Waals bonds. Consequently, more energy (and thus a higher temperature) is required to overcome these stronger bonds, leading to an increase in boiling points, as seen in the table: Neon ($27.3\,\text{K}$), Argon ($87.4\,\text{K}$), Krypton ($121.5\,\text{K}$), and Xenon ($166.6\,\text{K}$).

#### 3.2 Gecko adhesion: many tiny weak bonds add up

Another remarkable real-world example of van der Waals forces in action is gecko adhesion. Geckos can cling to and walk across smooth surfaces, even upside down, not through suction or glue, but through the collective effect of millions of tiny van der Waals contacts. Their feet are covered in an enormous surface area of microscopic hair-like structures called setae, which branch into even finer nanoscale fibrils. Each individual contact forms a very weak van der Waals bond with the surface, but the sheer number of these contacts creates a cumulative force strong enough to support the gecko's entire body weight. This principle has been mimicked to create "Gecko tape," a synthetic adhesive that uses high-surface-area microstructures to achieve impressive stickiness without traditional glues.

### 4) Latent heat: the “hidden” energy of bond breaking/forming

Latent heat is the energy absorbed or released by a substance during a phase change (such as vaporisation, fusion, or sublimation) at a constant temperature. This energy is "hidden" because it goes into changing the bonding state of the molecules rather than increasing their kinetic energy, which would result in a temperature rise. For example, the latent heat of vaporisation is the energy required to break the intermolecular bonds in a liquid so that it can transform into a gas.

To illustrate the significant amount of energy involved in latent heat, consider the difference between a scald from $1\,\text{g}$ of $100\,^\circ\text{C}$ water versus $1\,\text{g}$ of $100\,^\circ\text{C}$ steam when it contacts skin at approximately $35\,^\circ\text{C}$. For the $1\,\text{g}$ of water, the energy transferred to the skin is primarily "sensible heat" as it cools from $100\,^\circ\text{C}$ to $35\,^\circ\text{C}$, which is approximately $272\,\text{J}$. However, for the $1\,\text{g}$ of steam, there are two components of energy transfer. First, the steam must condense into liquid water, releasing its latent heat of condensation, which is about $2268\,\text{J}$. Second, this newly formed liquid water then cools to skin temperature, releasing an additional $272\,\text{J}$. Therefore, the steam transfers roughly an order of magnitude more energy to the skin due to the large amount of latent heat released during condensation. This makes steam scalds significantly more severe.

### 5) From macroscopic L_v to microscopic $\varepsilon$: counting neighbours

To bridge the gap between macroscopic measurements like latent heat and microscopic bond strength $\varepsilon$, we must consider how atoms interact with multiple neighbours in condensed phases (liquids and solids). The Lennard-Jones attractive potential decays rapidly (as $1/r^6$), meaning that interactions with distant atoms are much weaker and can often be neglected. Therefore, considering only the nearest neighbours is a reasonable approximation for calculating the total bonding energy.

The typical number of nearest neighbours, or coordination number $n$, varies with the phase:

* For liquids, $n$ is approximately $10$ on average, reflecting the less ordered, but still dense, arrangement of atoms.

* For close-packed solids, $n$ is exactly $12$, representing the most efficient way to pack spheres.

⚠️ **Exam Alert!** The lecturer explicitly stated: "And in a solid, that number is 12. So those numbers, and there are a few numbers I expect you remember for this course, and that's one of them." Students should remember the typical nearest neighbour counts: $n \approx 10$ for liquids and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.

When linking latent heat to per-bond energy, it's crucial to avoid double-counting. Each bond is shared between two atoms, so we include a factor of $1/2$. The latent heat of vaporisation per mole, $L_v$, can then be related to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ by:

$$L_v = \frac{1}{2} N_A n \varepsilon$$

where $N_A$ is Avogadro's number. This equation can be rearranged to find the microscopic separation energy per bond:

$$\varepsilon = \frac{2 L_v}{N_A n}$$

Let's apply this to an example like Neon. Given its latent heat of vaporisation $L_v = 1.75\,\text{kJ mol}^{-1}$, and assuming $n \approx 10$ for a liquid, we can calculate $\varepsilon$. Plugging in the values, we find $\varepsilon \approx 0.004\,\text{eV}$ per bond. This result provides a quantitative sense of scale, confirming that van der Waals bonds are indeed very weak, typically thousands of times weaker than the several electron-volt energies associated with strong covalent or ionic bonds.

### 6) Consolidation: what the parameters tell you physically

To summarise, the parameters we've discussed provide clear physical insights into interatomic interactions:

* $a_0$: This is the equilibrium separation distance between two atoms, where the net interatomic force is zero and the potential energy is at its minimum.

* $a$: In the Lennard-Jones potential, this parameter represents the distance at which the potential energy $V(r)$ crosses zero, serving as a useful effective atomic diameter or size parameter in the model.

* $\varepsilon$: This is the bond or separation energy per pair of atoms, equivalent to the depth of the potential well, and quantifies the energy required to break a single bond.

* $k$: This effective spring constant represents the curvature of the potential energy well at its minimum, indicating the stiffness of the "bond spring" for small oscillations.

It's important to keep the orders of magnitude in mind: van der Waals bonds typically have separation energies $\varepsilon$ in the range of $10^{-3}$ to $10^{-2}\,\text{eV}$, whereas strong bonds like ionic, covalent, or metallic bonds are significantly stronger, on the order of several electron volts.

## Appendix: Ionic bonding extra (Born-Landé outline)

*Side Note:* This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

This appendix outlines the more complex calculation for ionic bonding, which involves summing electrostatic interactions across an entire crystal lattice. This leads to the introduction of the Madelung constant, $\alpha$, which accounts for the specific geometric arrangement of ions in a crystal structure (e.g., $\alpha \approx 1.75$ for NaCl). Combining this with a short-range repulsive term, often modelled as $A/r^p$, allows for the derivation of the Born-Landé equation, which provides a theoretical value for the lattice energy of ionic solids.

## Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

Slides titled "Now let's consider the other bonding types" and subsequent slides detailing ionic, covalent (Morse potential), and metallic bonding were not covered in this lecture. These topics will be addressed in future sessions.

## Key takeaways

Near equilibrium, interatomic forces can be well-approximated by a linear restoring force, meaning atoms behave like masses on springs, with an effective spring constant $k = A(m - n)/a_0^{(m+1)}$. Integrating the two-term force model leads to the Lennard-Jones potential, from which we can directly read $\varepsilon$ (the well depth or bond strength), $a$ (a size parameter where $V=0$), and $a_0$ (the equilibrium separation at the potential minimum). Van der Waals forces, though weak per individual pair, are crucial for phenomena like noble gas liquefaction and gecko adhesion, where millions of tiny contacts sum to a significant collective force. Macroscopically, latent heat is the energy associated with bond breaking or forming during phase changes. This allows us to connect the latent heat of vaporisation, $L_v$, to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ through a neighbour counting argument, $L_v = (1/2) N_A n \varepsilon$. Typical coordination numbers are $n \approx 10$ for liquids and $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.

⚠️ **Exam Alert!** The lecturer explicitly stated: "And in a solid, that number is 12. So those numbers, and there are a few numbers I expect you remember for this course, and that's one of them." Students should remember that the typical coordination number for a close-packed solid is $n=12$.