Lecture 2: Interatomic Forces (part 1)

0) Orientation and learning outcomes

This course builds on the foundation of Lecture 1 by shifting our focus from individual particles to the collective behaviour of many-body systems. Our aim is to develop an atomic-level understanding of why matter exists in solid, liquid, and gaseous states, and eventually, to connect this microscopic picture to the principles of thermodynamics in later lectures.

A note on course materials: any content marked as an "Appendix" in these notes or the lecture slides is provided for your interest only and will not be included in examinations.

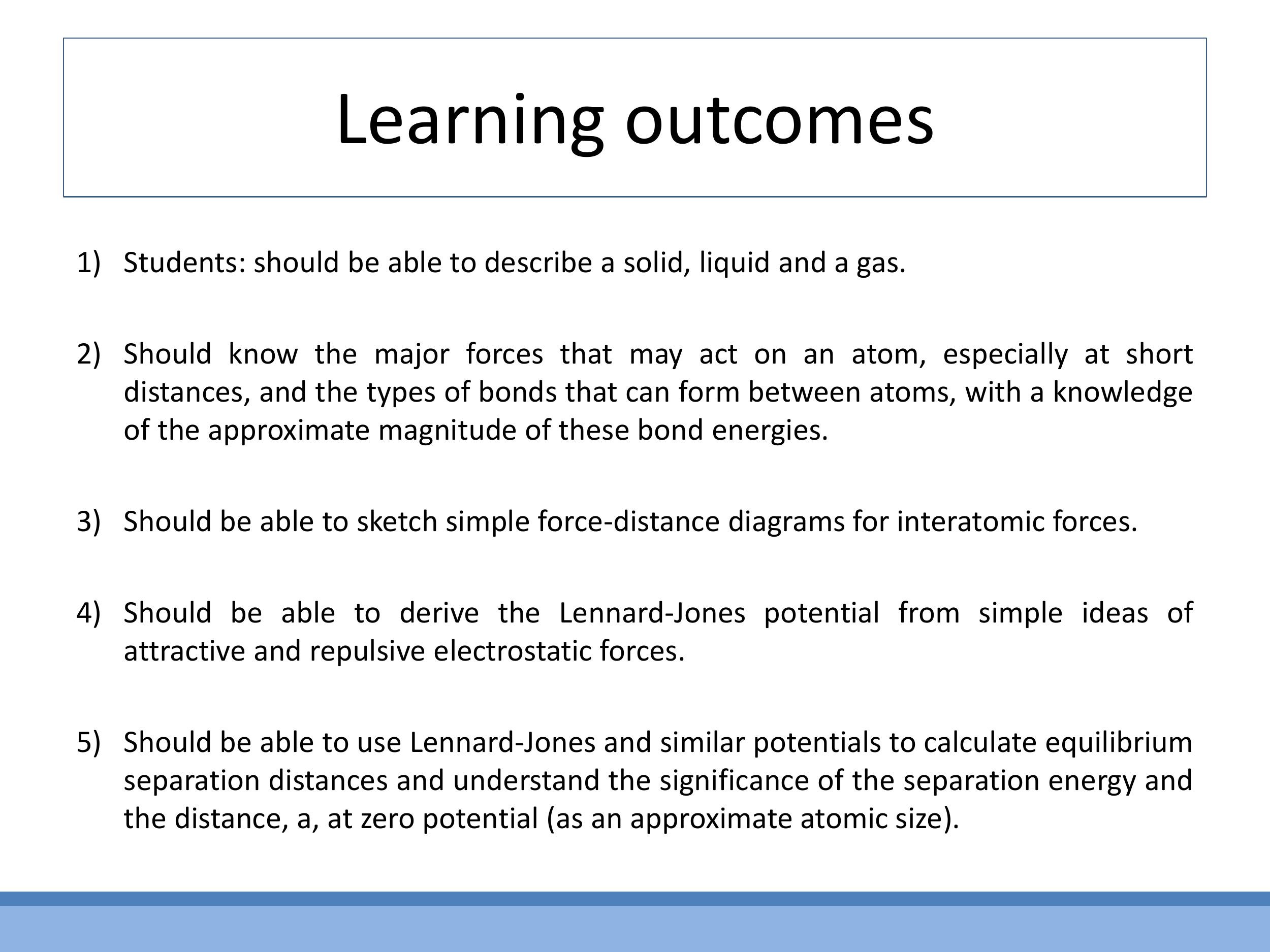

By the end of this lecture, you should be able to:

- Describe the physical properties that distinguish solids, liquids, and gases, such as compressibility, rigidity, and viscosity.

- Identify the main forces acting between atoms at short ranges, recognise different bond types, and understand their typical energy magnitudes.

- Sketch qualitative force-distance curves and pinpoint the equilibrium separation distance between atoms.

- Derive the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential from a two-term power law model for interatomic forces.

- Utilise Lennard-Jones-like potentials to determine equilibrium distances and interpret the physical significance of the parameters $\varepsilon$ (well depth) and $a$ (distance at which potential is zero), which approximates atomic size.

This lecture will explain why matter holds together and what determines the characteristic distances between atoms in condensed phases.

1) Why both attraction and repulsion must exist

The existence of solids and liquids in our everyday lives, such as tables and sofas, provides intuitive evidence that atoms must attract each other. Without an attractive force, matter would not condense into these stable forms.

However, if attraction were the only force at play, all matter would simply collapse into itself. The fact that matter maintains stable, finite volumes and structures implies the presence of a counteracting, short-range repulsive force. This balance between attraction and repulsion is crucial for the stability of matter.

The primary origin of this strong, short-range repulsion is a quantum mechanical effect described by the Pauli exclusion principle. This principle states that no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state. As atoms approach each other, their electron wavefunctions begin to overlap. To prevent this overlap, a very steep and powerful repulsive force arises, pushing the atoms apart. While Coulomb repulsion between the positively charged nuclei also exists, the Pauli exclusion principle is the dominant mechanism for short-range repulsion at typical interatomic distances.

We can visualise this balance of forces with a simple analogy: imagine a set of "inverter magnets" where you have a weak, long-range attraction and a strong, short-range repulsion. If you try to push them too close, they strongly resist, but if you pull them too far apart, they weakly attract. This creates a stable "sweet spot" separation, and if displaced, they "snap back" to this equilibrium distance. This demonstration helps build intuition for the stable interatomic separations observed in real materials.

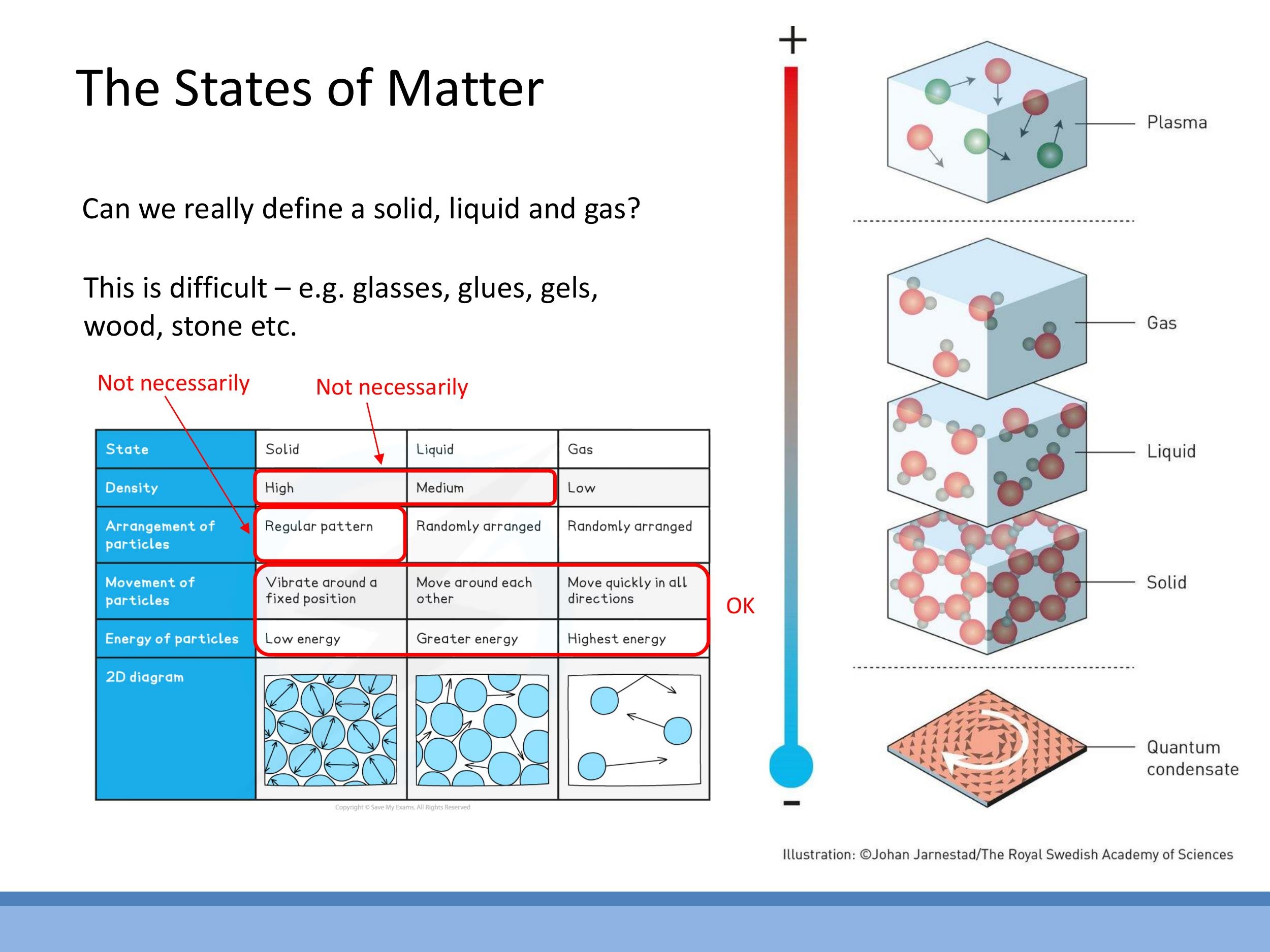

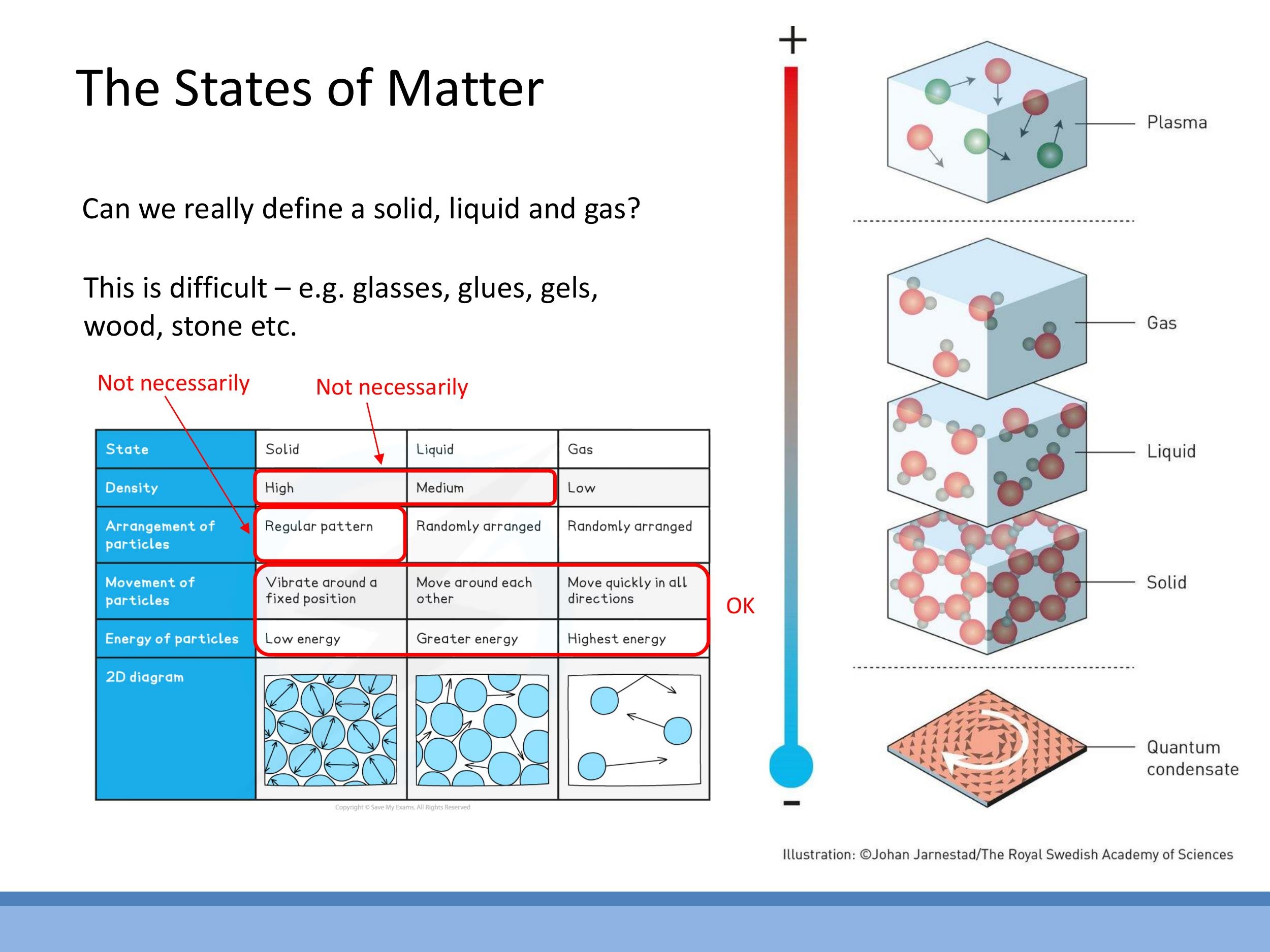

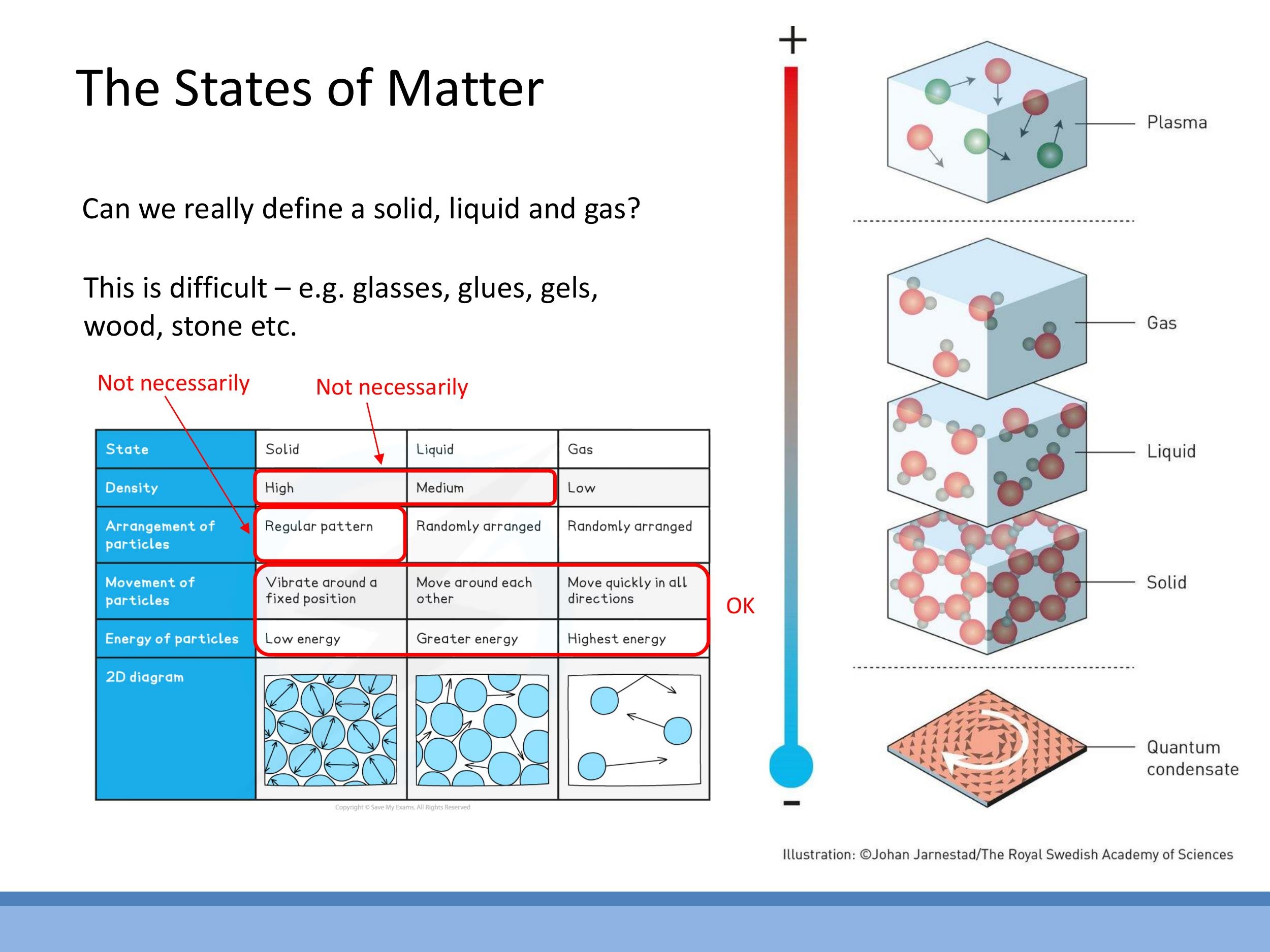

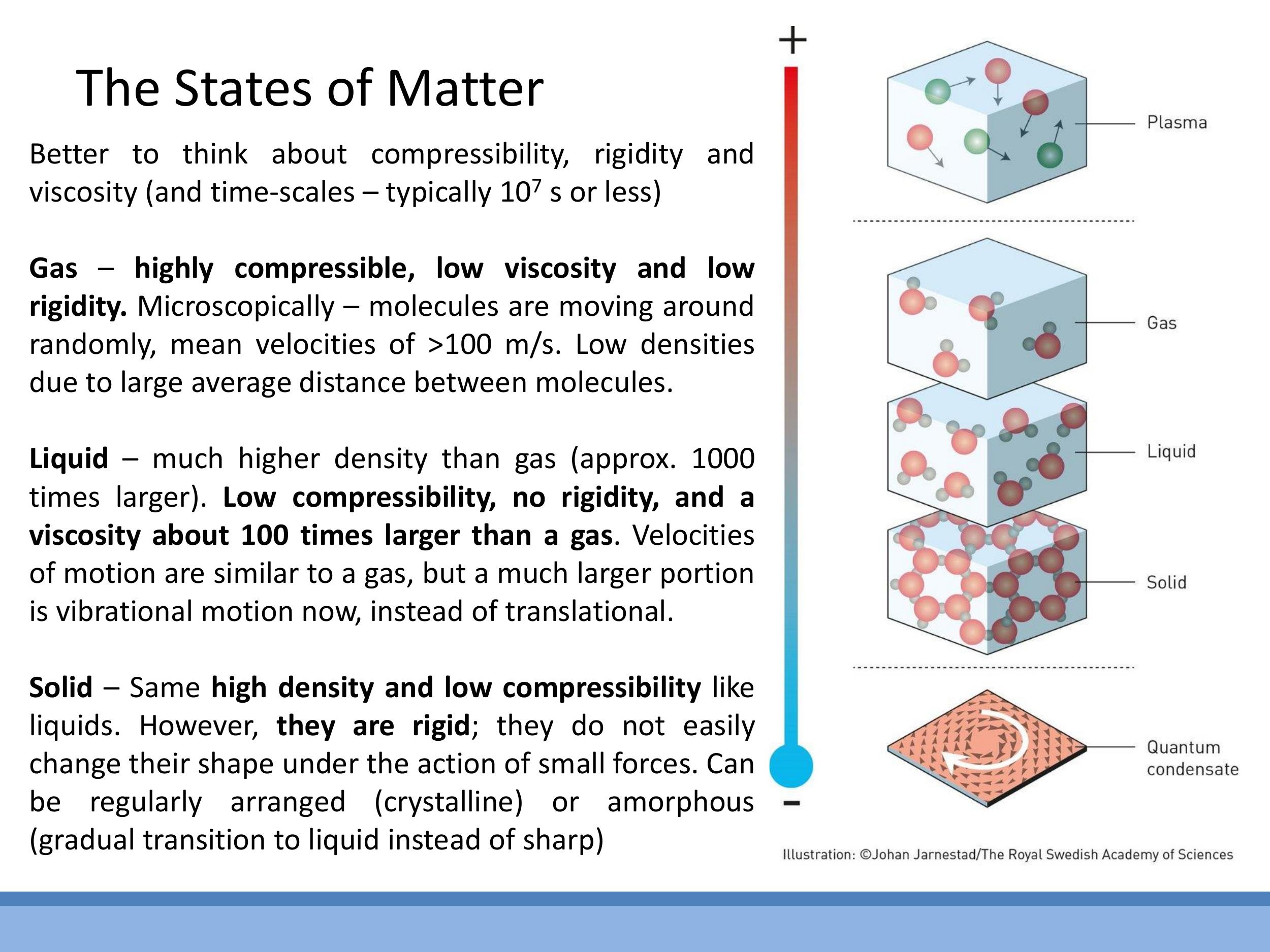

2) States of matter: beyond the GCSE table

Simplified definitions of the states of matter, often encountered at GCSE level, can be misleading. For instance, the generalisation that solids are always denser than liquids, which are denser than gases, has exceptions. Ice is less dense than liquid water, and elements like silicon and germanium also exhibit this anomalous behaviour. Similarly, defining a solid by a "regular pattern" (i.e., being crystalline) isn't universally true, as amorphous solids like glass, as well as polymers and plastics, are solids that lack a regular, periodic atomic structure.

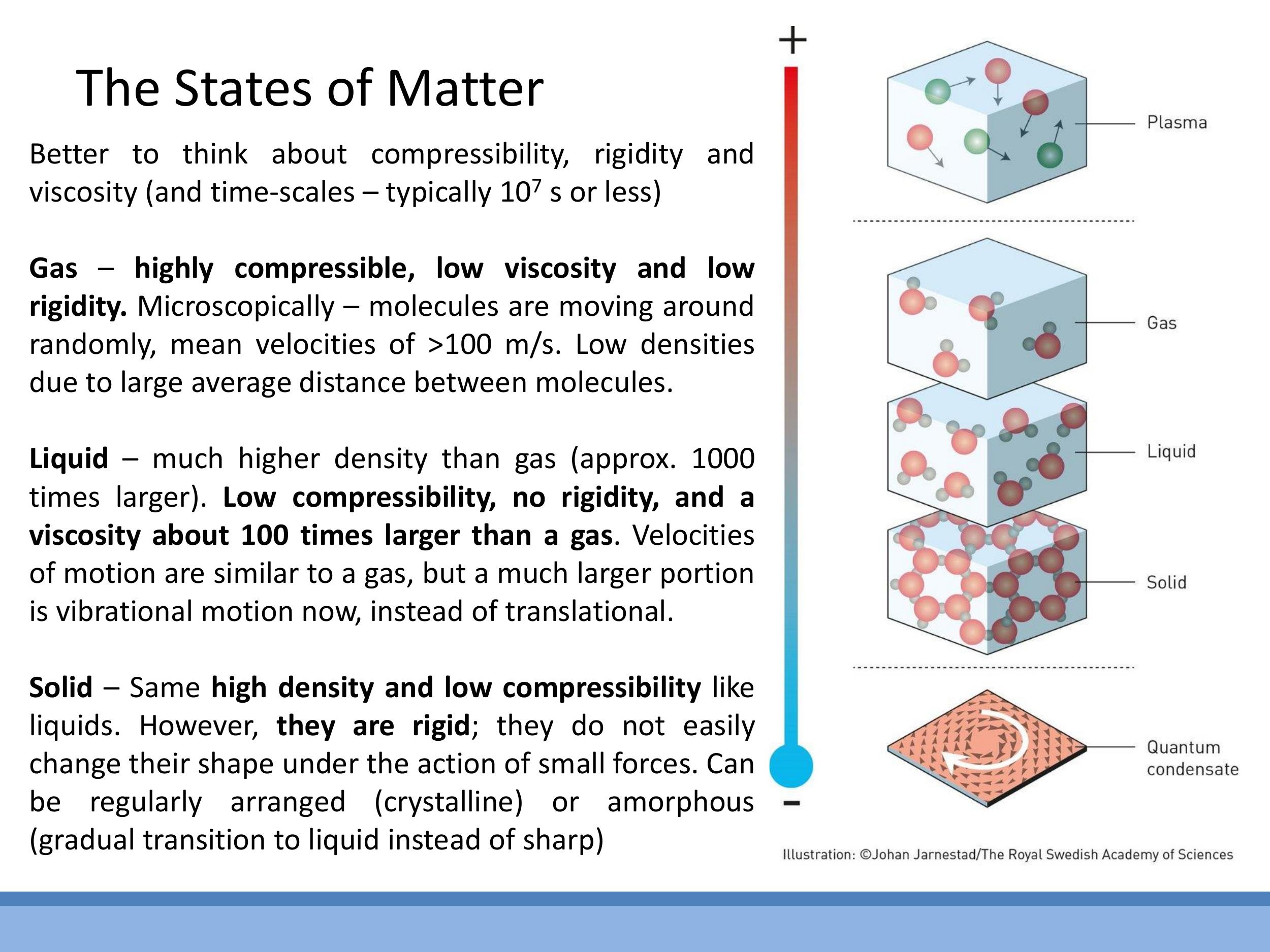

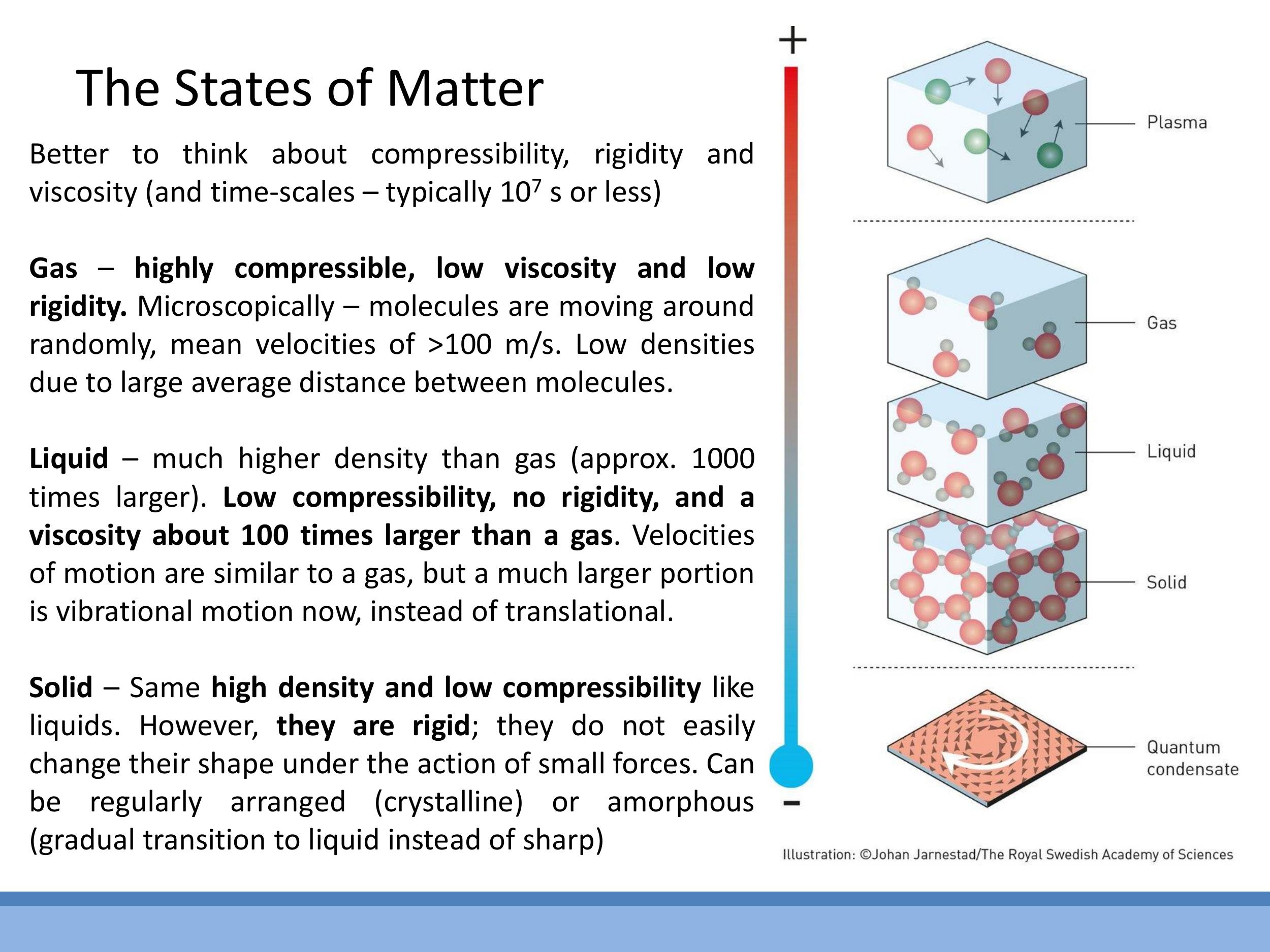

A more robust physical characterisation of the states of matter relies on properties like compressibility, rigidity, and viscosity, along with a microscopic understanding of particle motion:

- Gas: Gases are highly compressible, exhibit low rigidity, and have low viscosity. Microscopically, their particles are far apart and move randomly at high velocities. For example, nitrogen molecules in room-temperature air (around $20 \, ^\circ\text{C} $) have a root mean square speed of approximately $ 500 \, \text{m s}^{-1} $, which is roughly $ 1000 \, \text{mph}$. This high speed contributes to their large mean free path and low density.

- Liquid: Liquids have very low compressibility, similar to solids, but possess no rigidity, meaning they flow and take the shape of their container. Their viscosity is typically about $100$ times greater than that of a gas. At a microscopic level, liquid molecules are much closer together than in a gas, allowing them to move past one another. Their motion is a mixture of translational and vibrational components.

- Solid: Solids are rigid and have low compressibility. Their atoms vibrate about fixed positions within a structure, with negligible translational motion. This fixed arrangement gives solids their characteristic shape and resistance to deformation.

Side Note: While this course focuses on solids, liquids, and gases, it's worth noting that these make up less than $1 \% $ of the ordinary matter in the observable universe. The vast majority of ordinary matter exists as plasma, such as in stars and nebulae.

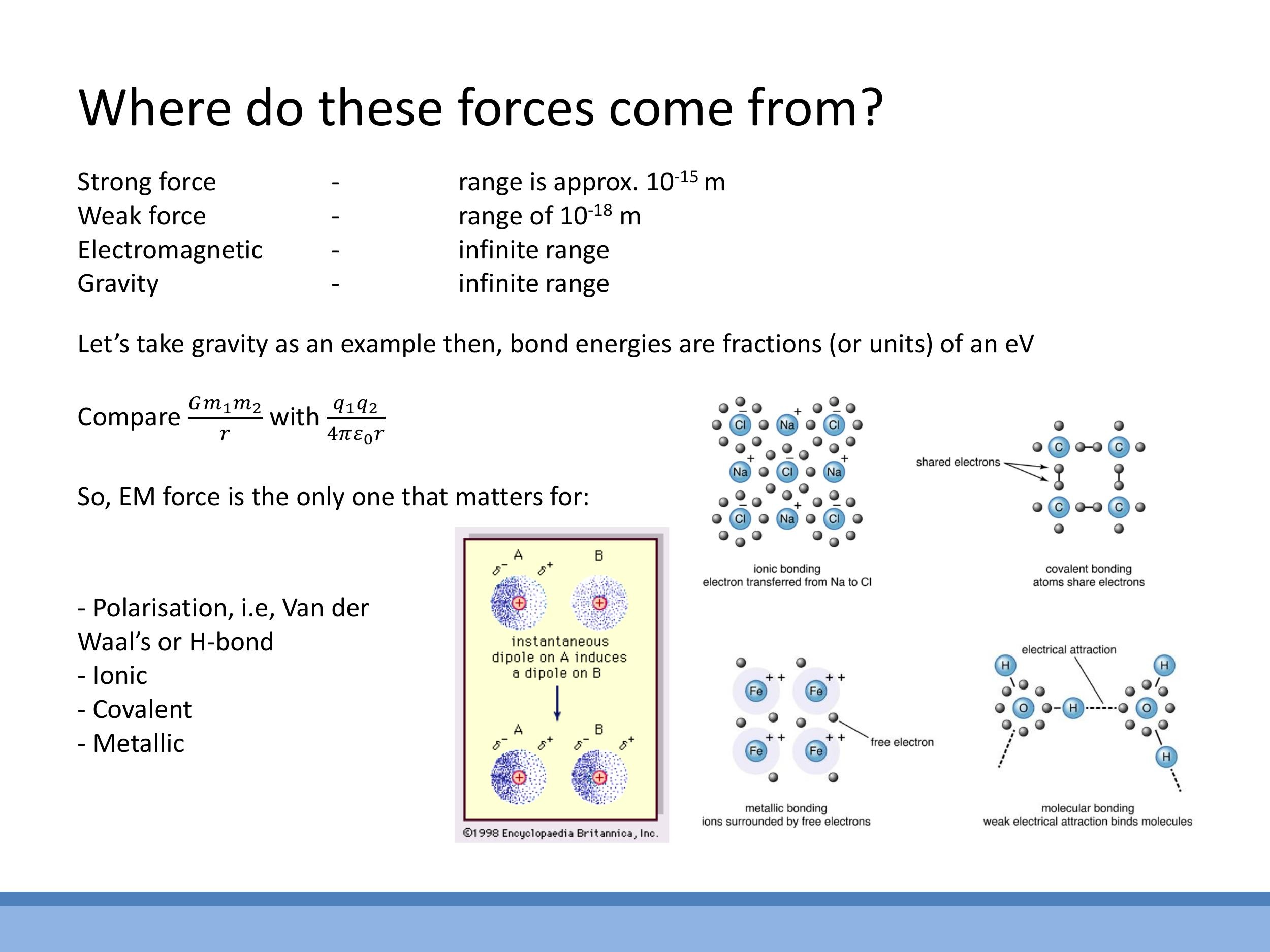

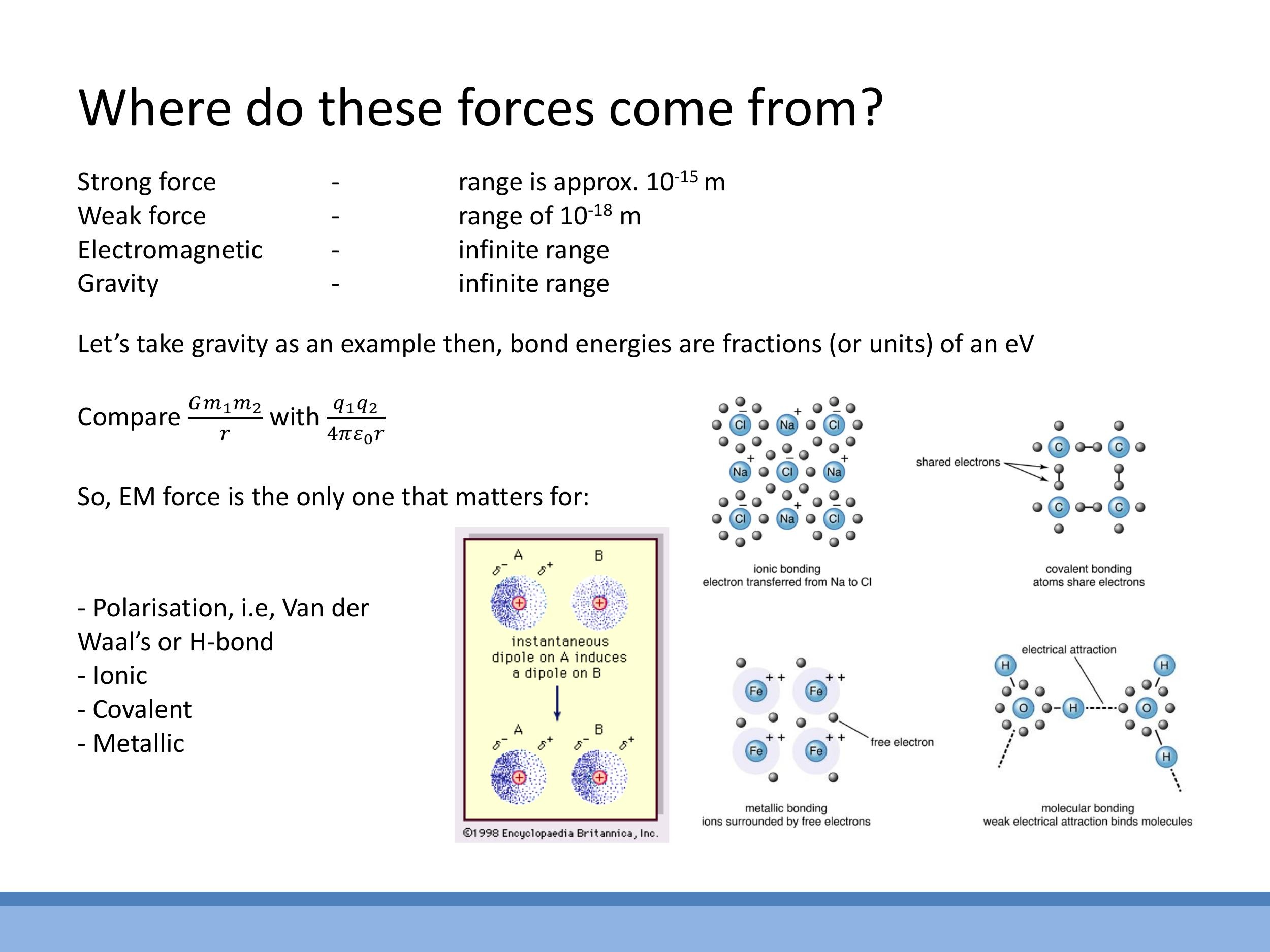

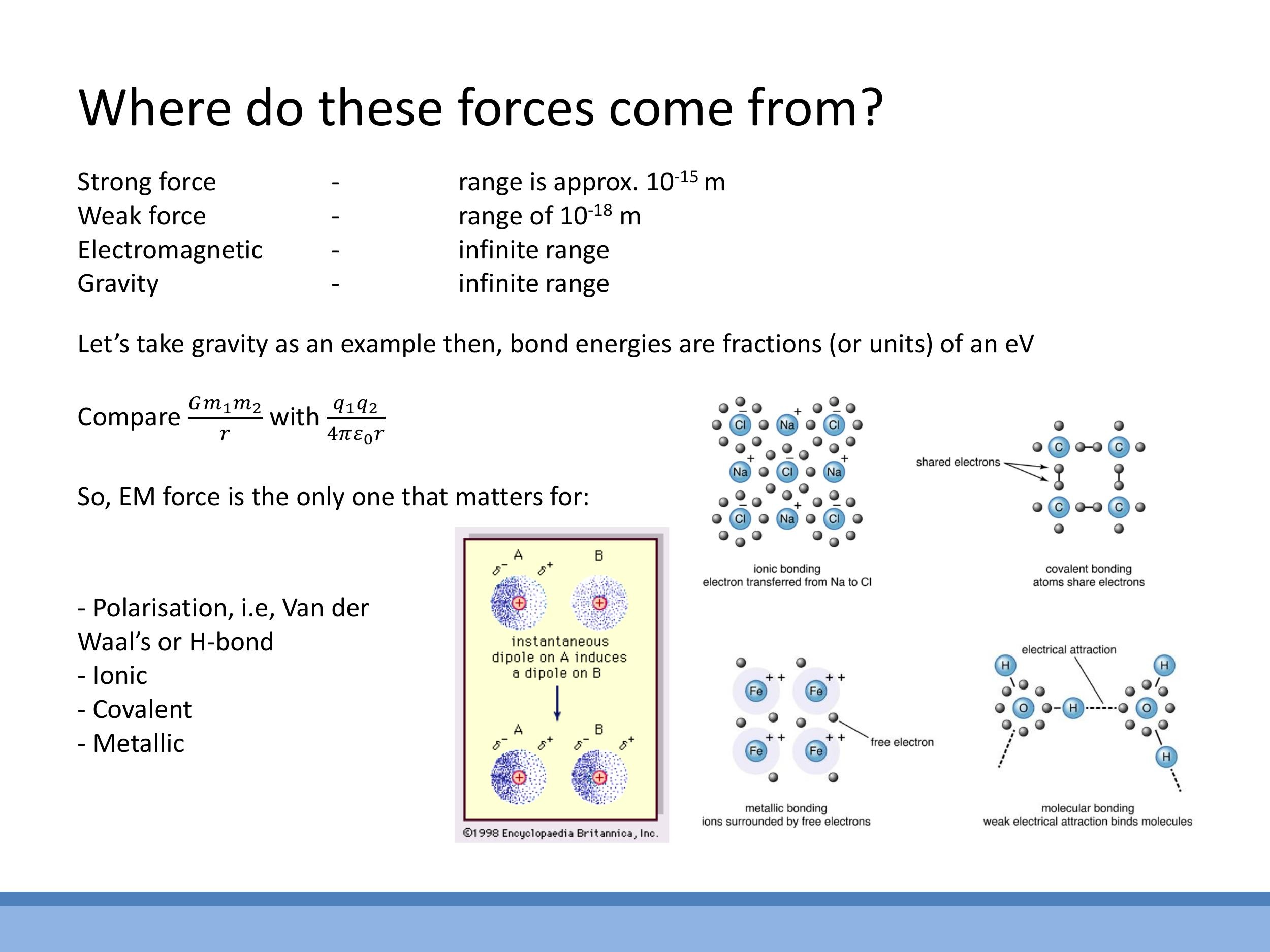

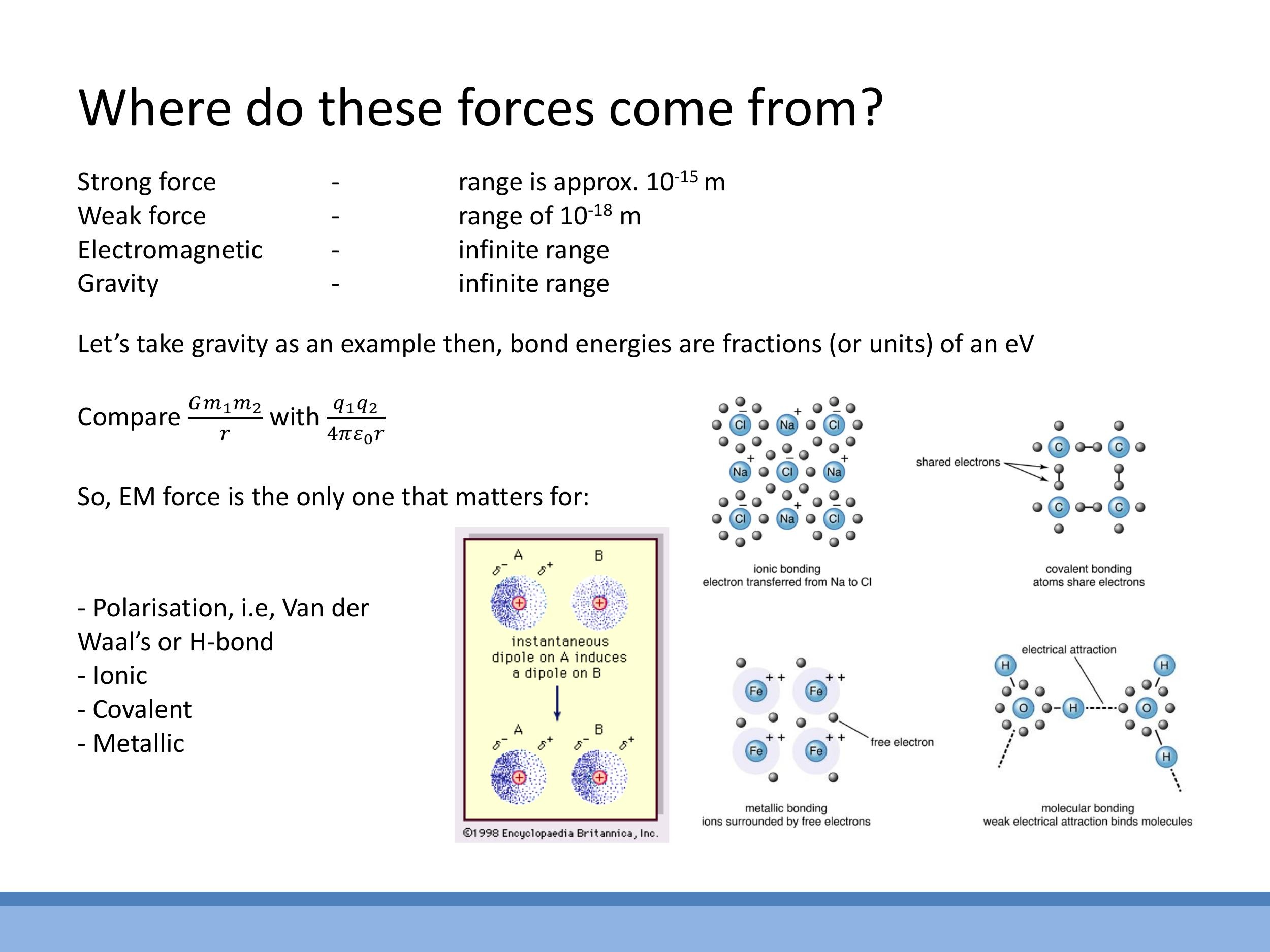

3) Which fundamental force binds atoms? Range and scale

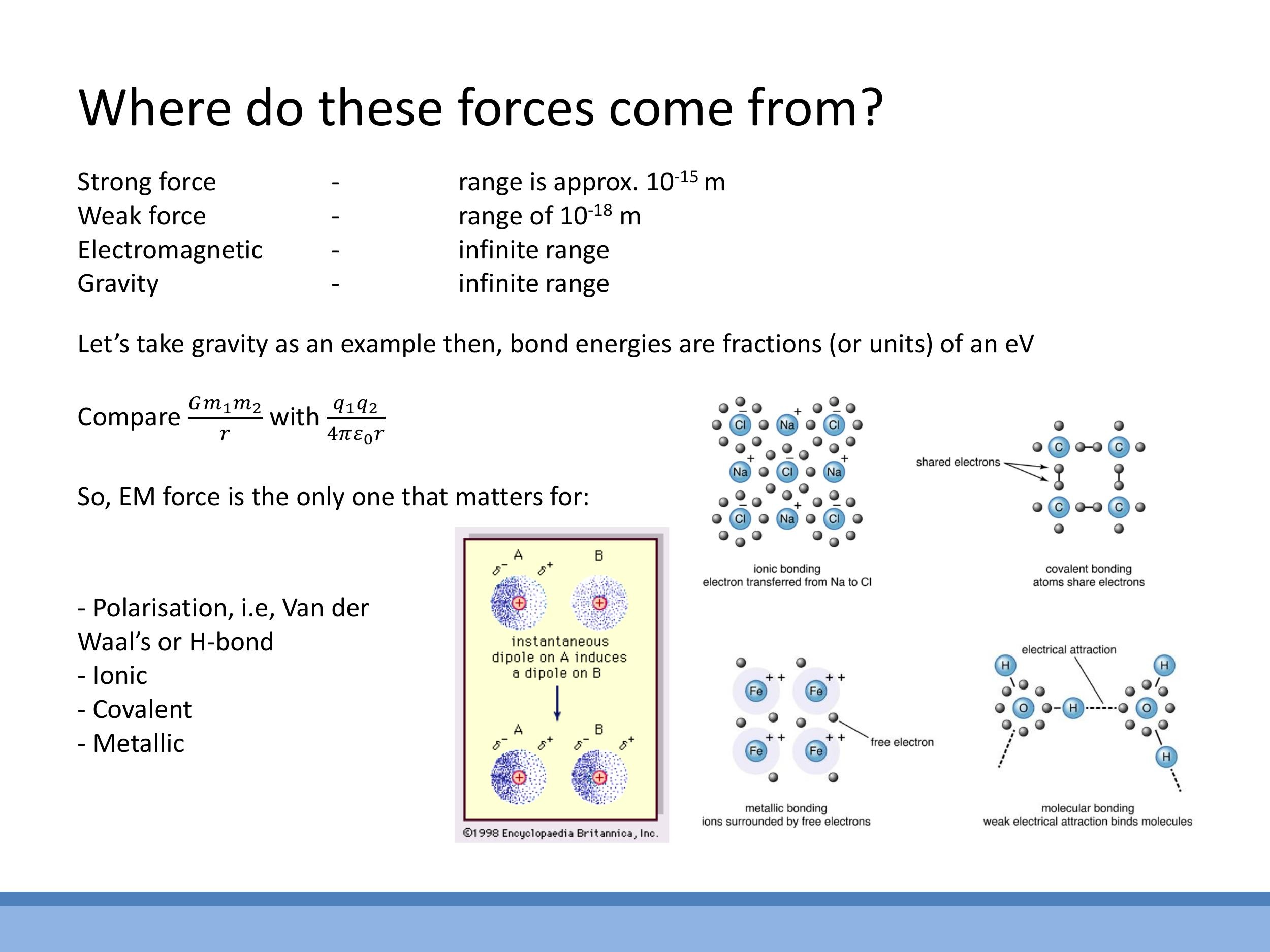

To understand which fundamental force is responsible for interatomic bonding, we first consider their typical ranges:

- Strong force: Approximately $10^{-15} \, \text{m}$ (a femtometre or Fermi).

- Weak force: Approximately $10^{-18} \, \text{m}$.

- Electromagnetic force: Infinite range.

- Gravity: Infinite range.

Given that typical interatomic separations are around $10^{-10} \, \text{m} $, which is $ 1 \, \text{Ångström} $ ($ \text{Å}$), the strong and weak nuclear forces are too short-ranged to play a direct role in bonding atoms together.

⚠️ Exam Alert! The lecturer explicitly stated that knowing the $\text{Ångström}$ scale ($10^{-10} \, \text{m}$) is very useful for multiple-choice questions in December and longer questions in the summer exam. Having an idea of sensible atomic distances will help you determine if your calculations are on the right track.

This leaves us with electromagnetism and gravity. To determine which dominates, let's perform an order-of-magnitude test. Consider two hypothetical atoms, each with a mass of $100 \, \text{u} $ (atomic mass units) and charges of $ \pm e $ (for an ionic bond), separated by a distance $ r = 1.5 \, \text{Å} = 1.5 \times 10^{-10} \, \text{m}$.

We can calculate their gravitational and electrostatic potential energies:

- Gravitational potential energy: $U_g = -\frac{G m_1 m_2}{r}$

- Electrostatic potential energy: $U_e = \frac{q_1 q_2}{4\pi\varepsilon_0 r}$

Using the relevant constants ($G \approx 6.67 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{N m}^2 \text{kg}^{-2} $, $ 1/(4\pi\varepsilon_0) \approx 8.99 \times 10^9 \, \text{N m}^2 \text{C}^{-2} $), and converting the results to electron volts ($ \text{eV}$) for easier comparison with typical bond energies:

- $U_g \approx 7.65 \times 10^{-32} \, \text{eV}$

- $U_e \approx 9.6 \, \text{eV}$

This calculation clearly shows that the electrostatic force is approximately $10^{32}$ times stronger than the gravitational force at interatomic distances. Therefore, electromagnetism is the only force that significantly contributes to interatomic bonding.

4) Bond types as manifestations of electrostatics

All interatomic bonds are manifestations of electrostatic interactions, though they differ in how electrons are distributed or transferred.

- Ionic bonds form when electrons are completely transferred from one atom to another, creating oppositely charged ions (cations and anions) that are then strongly attracted by the Coulomb force. Sodium chloride ($\text{NaCl}$) is a classic example.

- Covalent bonds involve the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. This sharing creates strong, often directional bonds that hold atoms together.

- Metallic bonds are characterised by a "sea" of delocalised valence electrons that are shared among a lattice of positive ion cores. This results in strong, non-directional bonding that accounts for the characteristic properties of metals.

Beyond these strong bonds, there are also weaker polar interactions:

- Hydrogen bonds are a specific type of dipole-dipole interaction that occurs when hydrogen is bonded to a highly electronegative atom (like oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine), creating a permanent dipole which can then attract other polar molecules.

- Van der Waals forces, also known as London dispersion forces, arise from temporary, induced dipoles. These are typically weaker than hydrogen bonds and are discussed in more detail below.

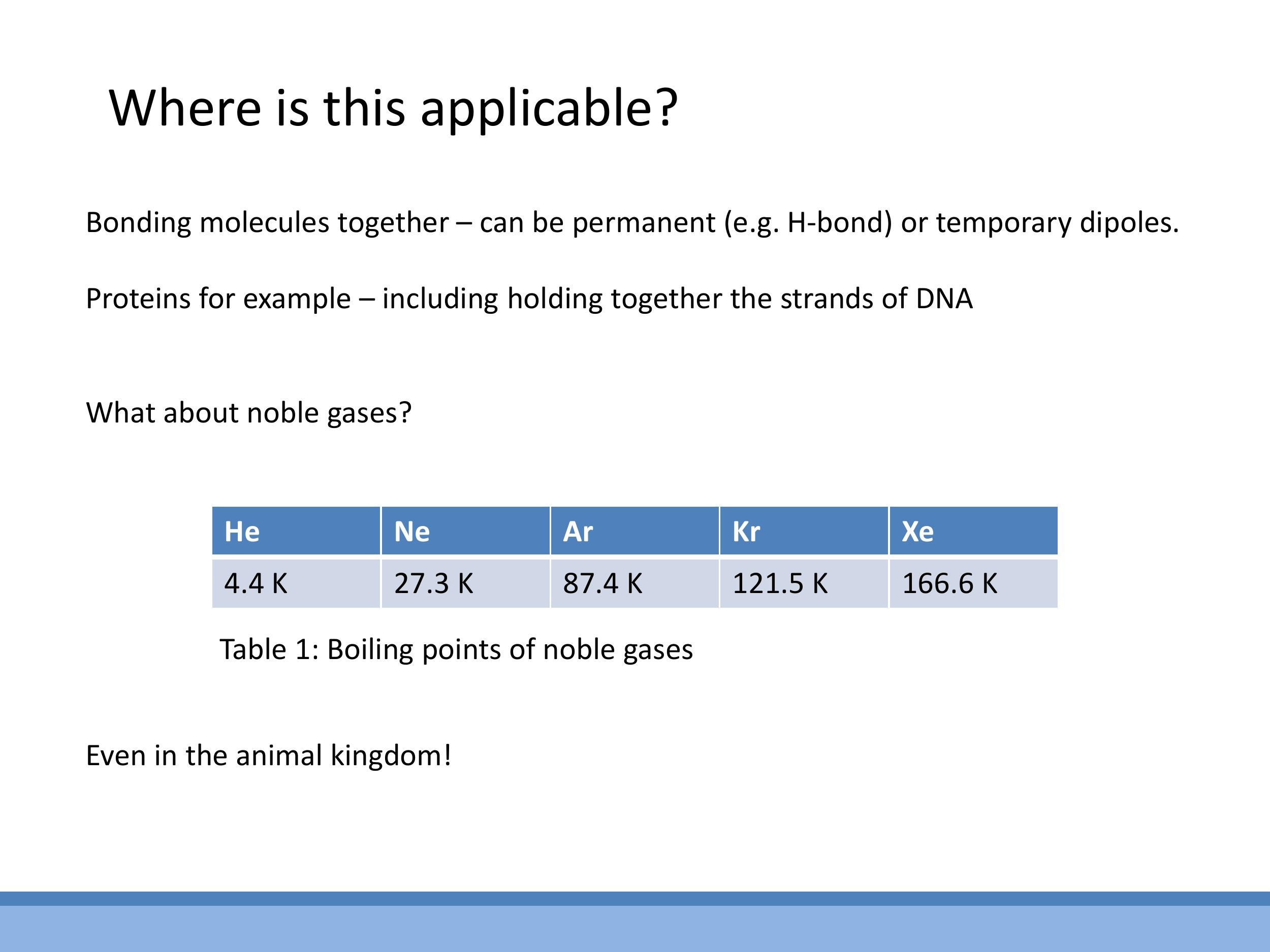

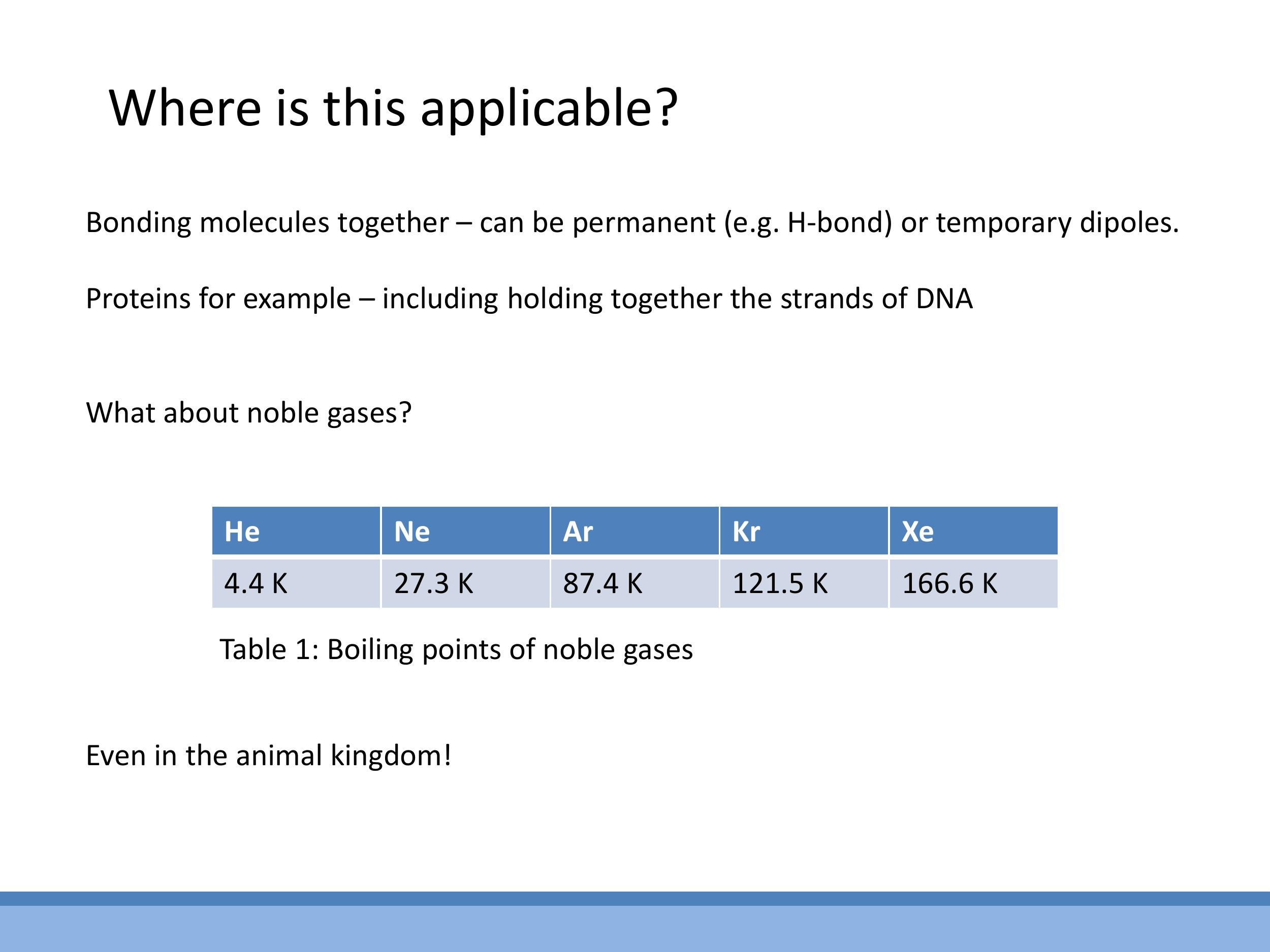

5) Van der Waals forces and noble gases

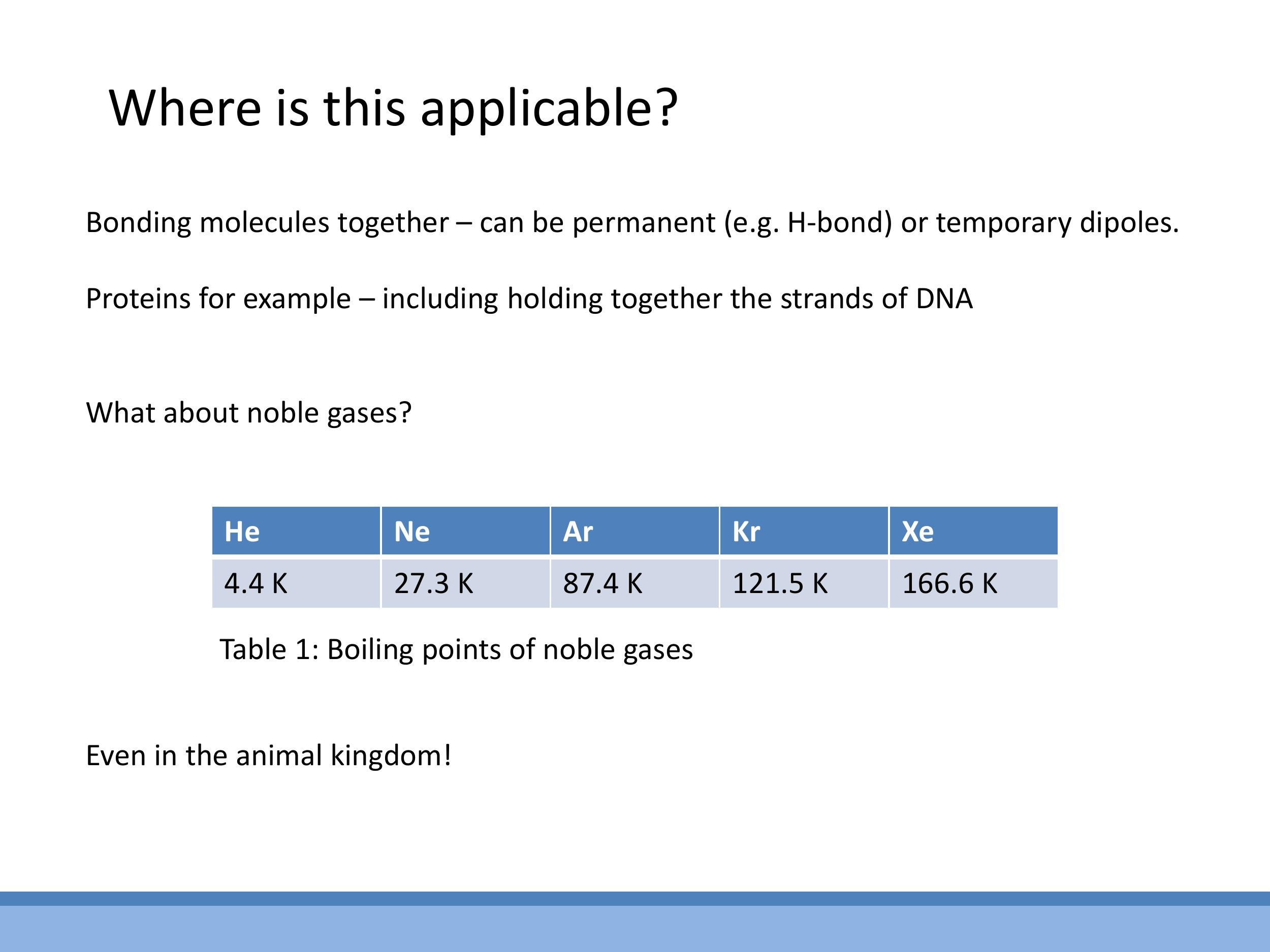

The existence of van der Waals forces helps us solve a puzzle: noble gases like helium ($\text{He}$), neon ($\text{Ne}$), and argon ($\text{Ar}$) are electrically neutral and have full electron shells, meaning they are chemically inert. Yet, when cooled sufficiently, they liquefy. What force holds these atoms together?

The mechanism behind this is called London dispersion. Although noble gas atoms are neutral on average, at any given instant, the electrons in an atom's cloud might be momentarily unevenly distributed, creating a transient, instantaneous dipole. This temporary dipole can then induce a corresponding dipole in a neighbouring atom, leading to a weak, short-lived attractive force between them. These induced-dipole interactions are responsible for the liquefaction of noble gases.

Empirical data supports this mechanism. As you move down the noble gas group from helium to xenon ($\text{Xe}$), the atoms become larger and have more electrons, making their electron clouds more polarisable (i.e., easier to distort and form temporary dipoles). This increased polarisability leads to stronger London dispersion forces, which in turn require more energy to overcome, resulting in higher boiling points. The boiling points of noble gases increase significantly down the group, consistent with the strengthening of these dispersion forces.

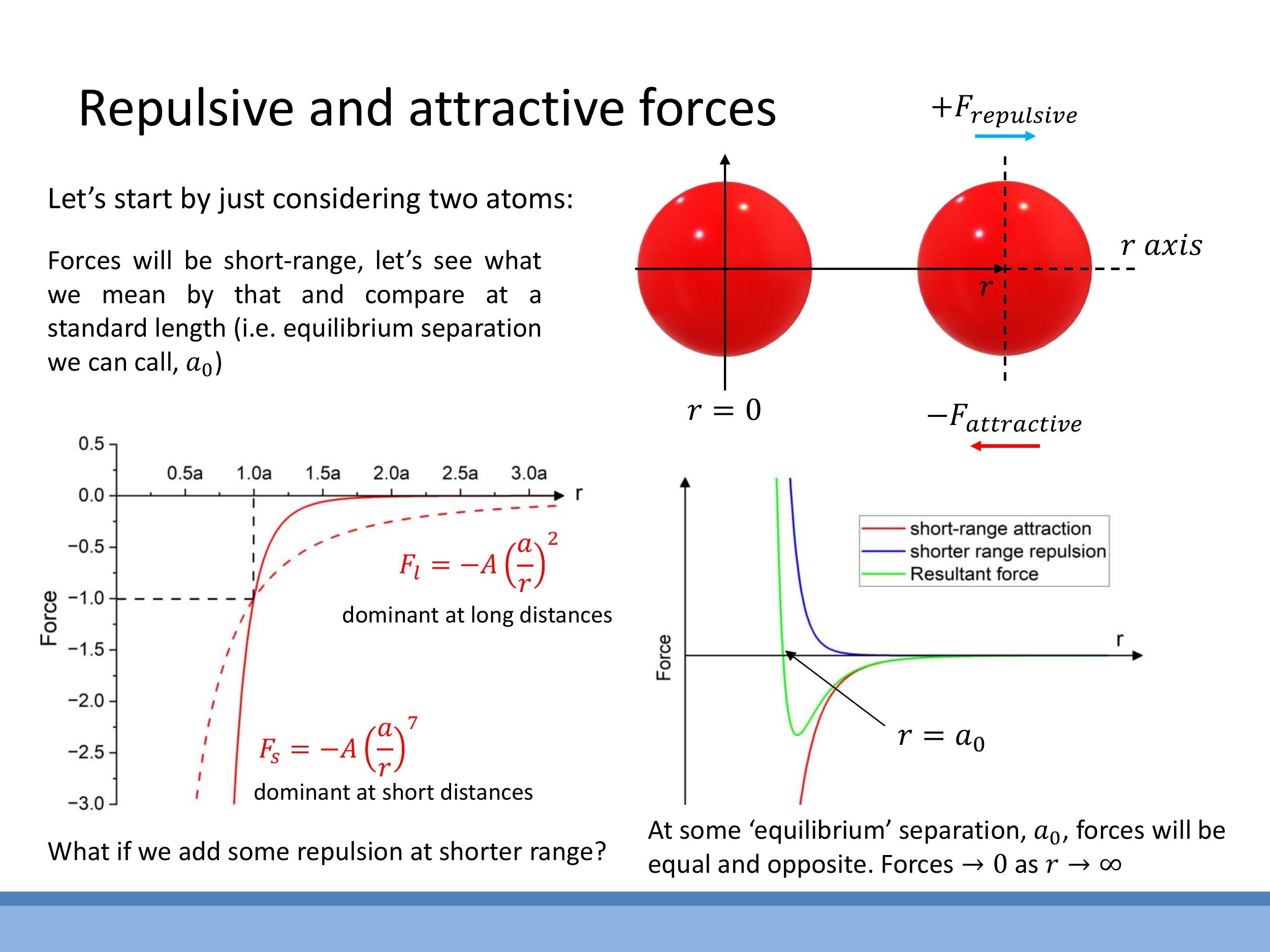

6) A simple interatomic force model: two-term power law

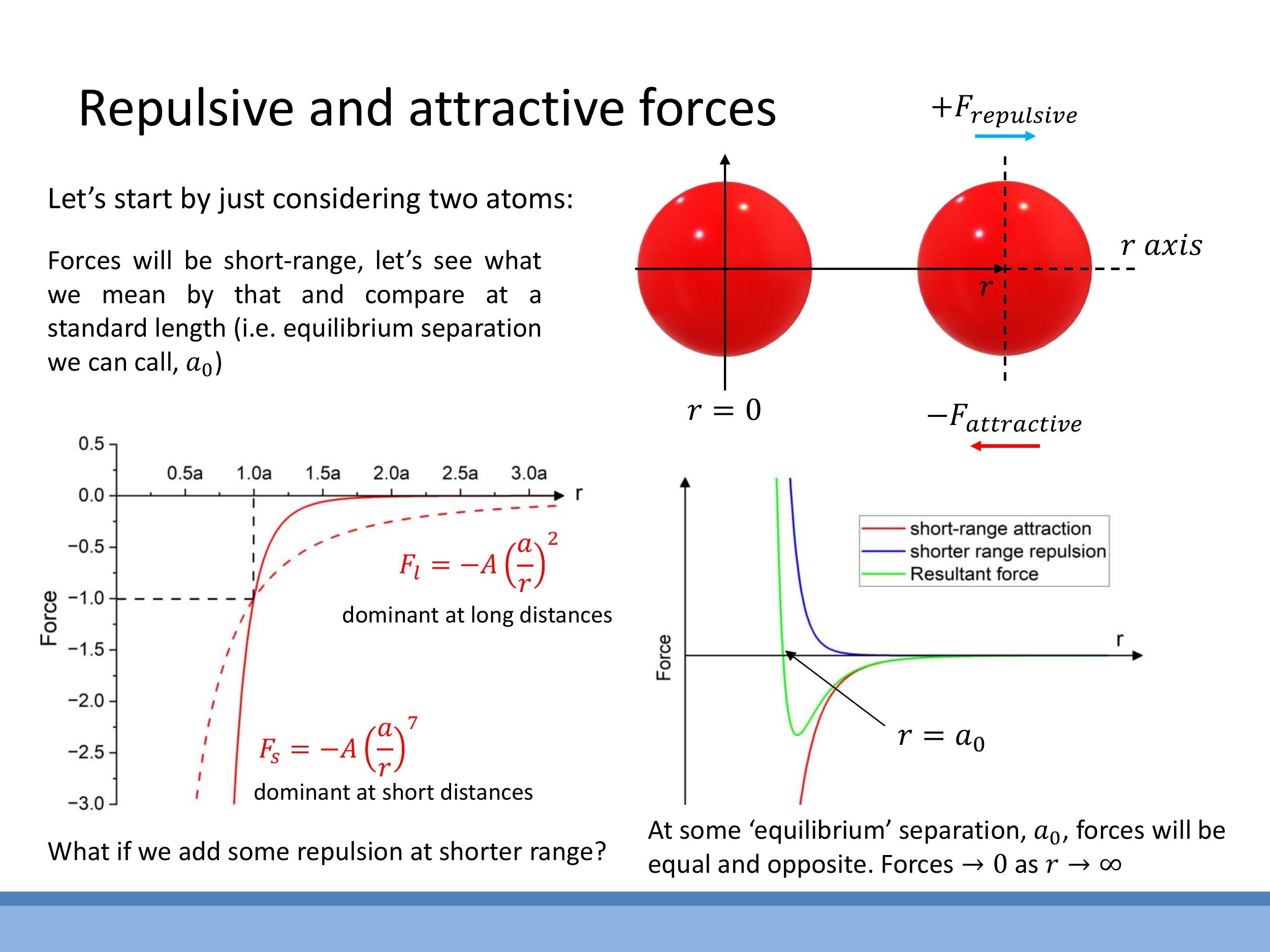

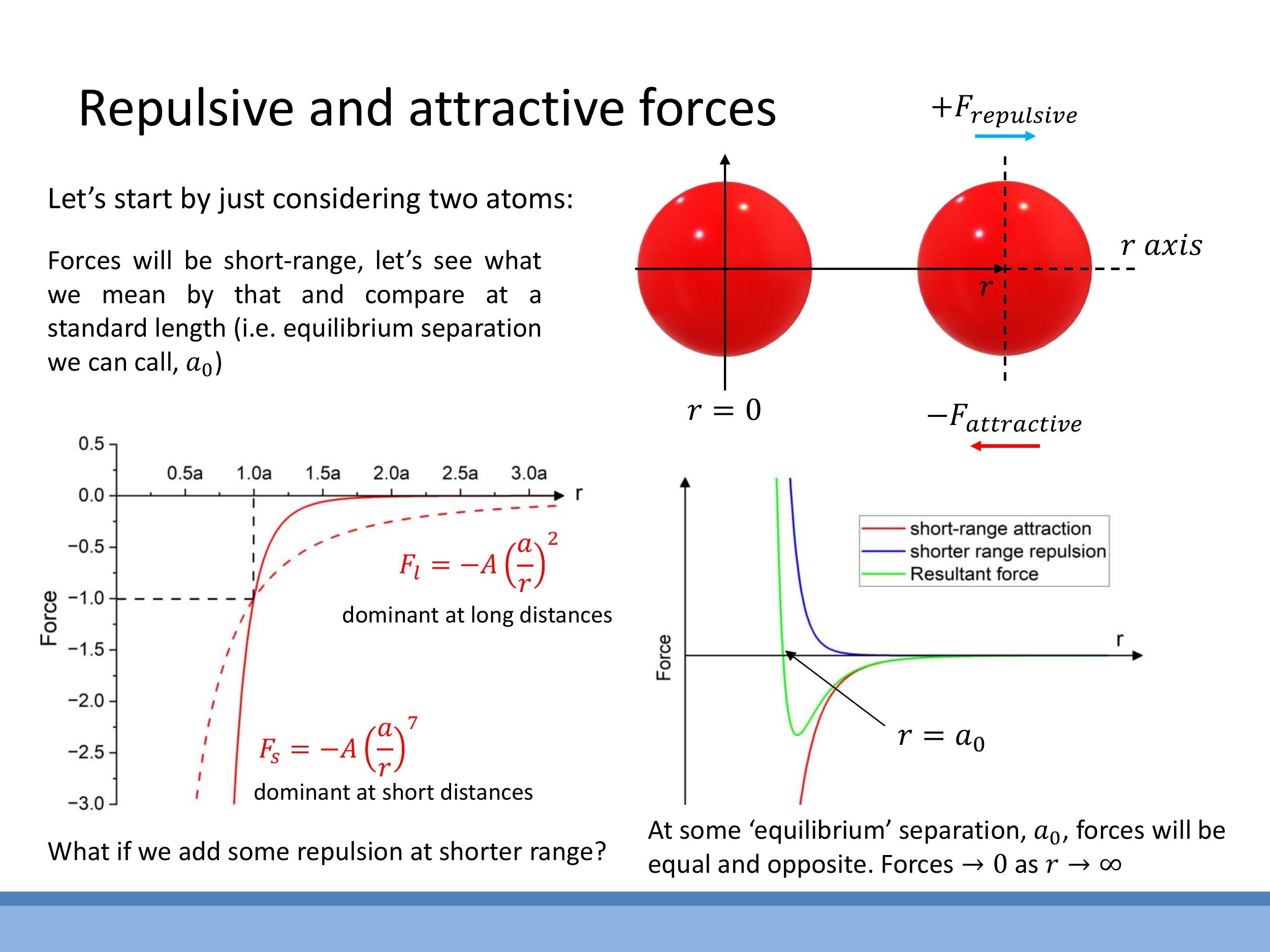

To quantitatively model interatomic forces, we can represent the net force $F(r)$ between two atoms as the sum of a short-range repulsive term and a longer-range attractive term. A common approach uses a two-term power law:

$$

F(r) = \frac{A}{r^m} - \frac{B}{r^n}

$$

Here, the $\frac{A}{r^m}$ term represents the repulsion, and the $-\frac{B}{r^n}$ term represents the attraction (the negative sign indicates an attractive force in the direction of decreasing $r$). For this model to prevent matter from collapsing, the repulsive force must be much steeper and shorter-ranged than the attractive force, meaning the exponent $m$ must be greater than $n$. At very short distances, the repulsive force (due to Pauli exclusion) dominates, rising sharply. At longer distances, the attractive force (e.g., van der Waals) is stronger, creating a shallow well before the force eventually approaches zero as $r \to \infty$.

The equilibrium separation distance, denoted as $a_0$, is the "sweet spot" where the attractive and repulsive forces perfectly balance, meaning $F(a_0) = 0$. From this condition, we can relate the coefficients $A$ and $B$:

$$

B = A a_0^{n-m}

$$

Substituting this back into the force equation allows us to express $F(r)$ in terms of $a_0$. For van der Waals systems, typical empirical exponents are $m \approx 13$ for the repulsive term and $n \approx 7$ for the attractive term.

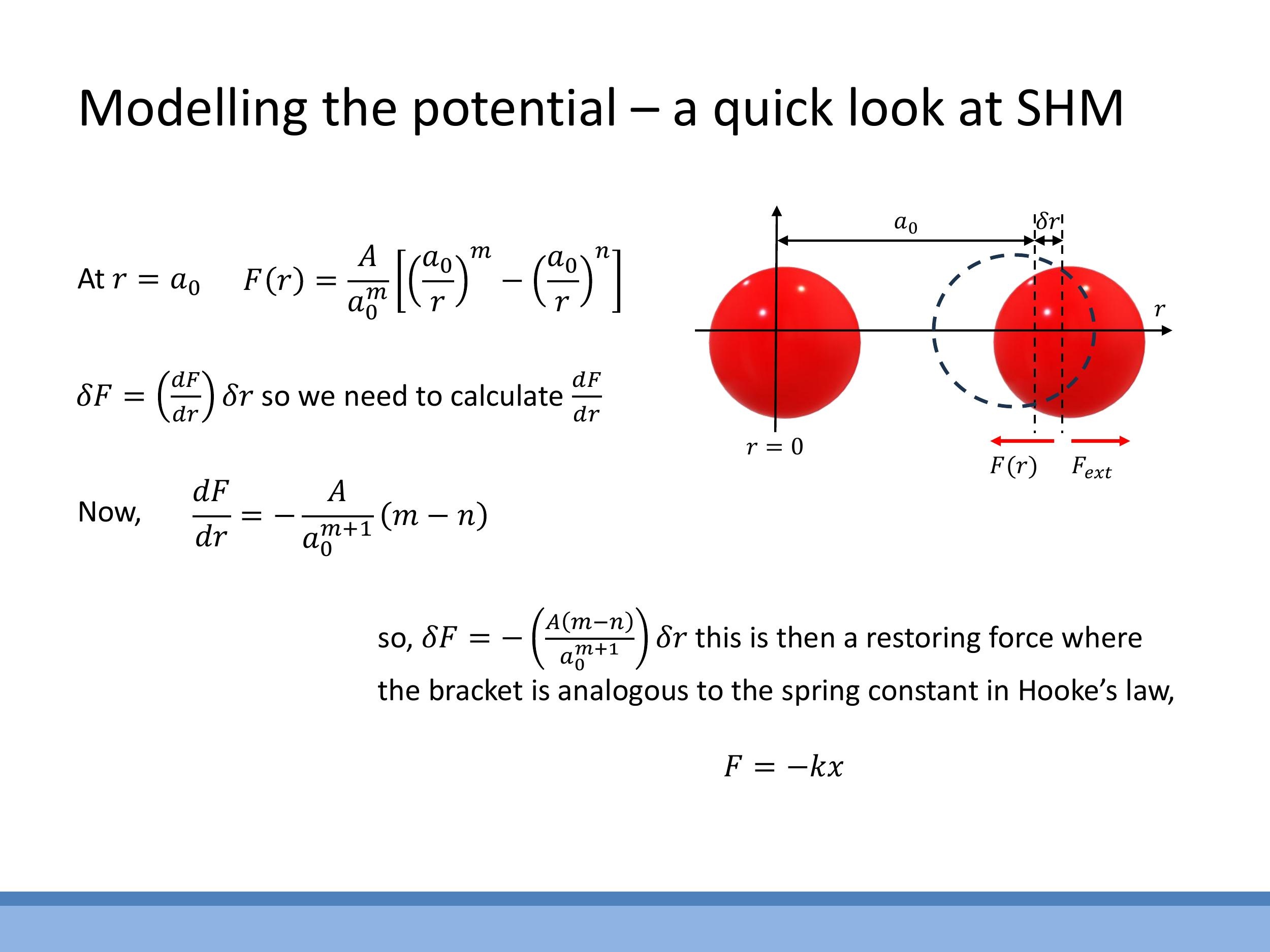

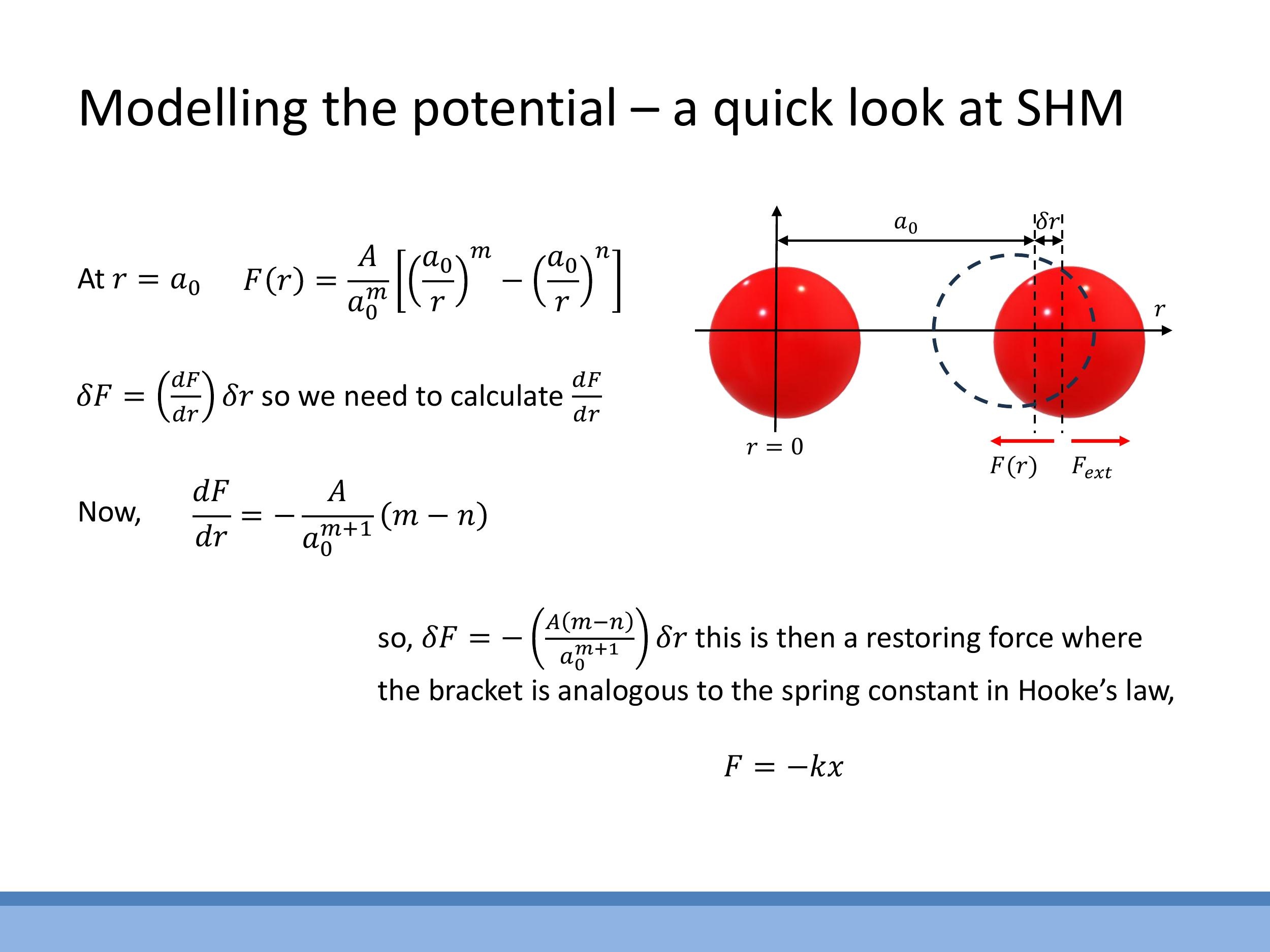

7) Near equilibrium: atoms behave like masses on springs (SHM)

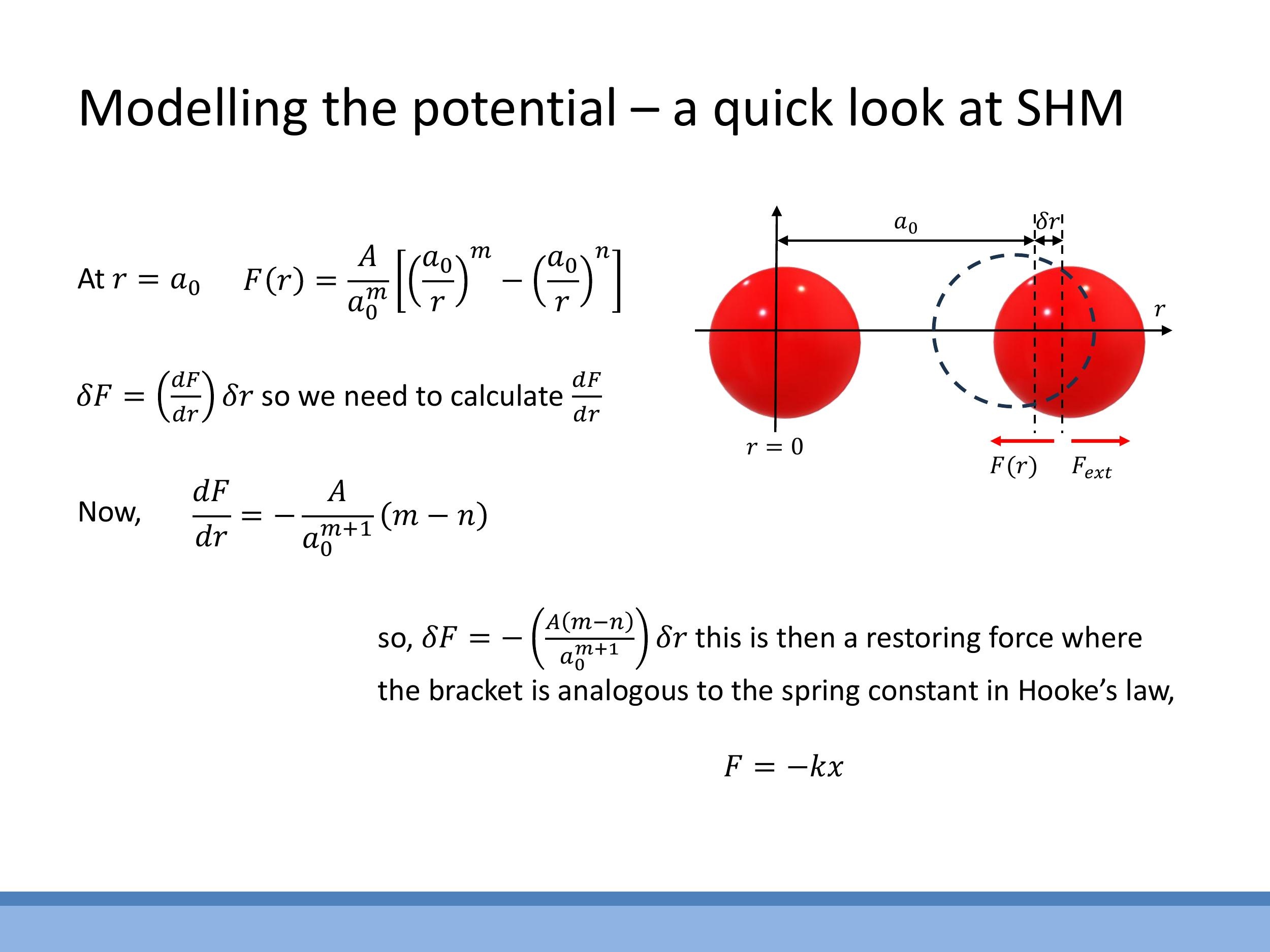

For small displacements ($\delta r$) around the equilibrium separation $a_0$, the interatomic force curve can be approximated as linear. This is analogous to Hooke's law for a spring. If an atom is slightly displaced from $a_0$, a restoring force $\delta F$ acts to bring it back to equilibrium. This restoring force is given by the gradient of the force curve at $a_0$:

$$ \delta F = \left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right) {r=a_0} \cdot \delta r $$

By comparing this to Hooke's law, $F = -k x$, we can identify an effective spring constant $k \text{eff} = -\left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right)_{a_0}$. This model implies that atoms in a solid or liquid vibrate about their equilibrium positions, much like masses attached to springs.

This "atoms-as-springs" picture is fundamental to understanding phenomena like thermal conductivity in non-metals. In these materials, heat is primarily transported by lattice vibrations, known as phonons, which are quantised packets of vibrational energy moving through the material.

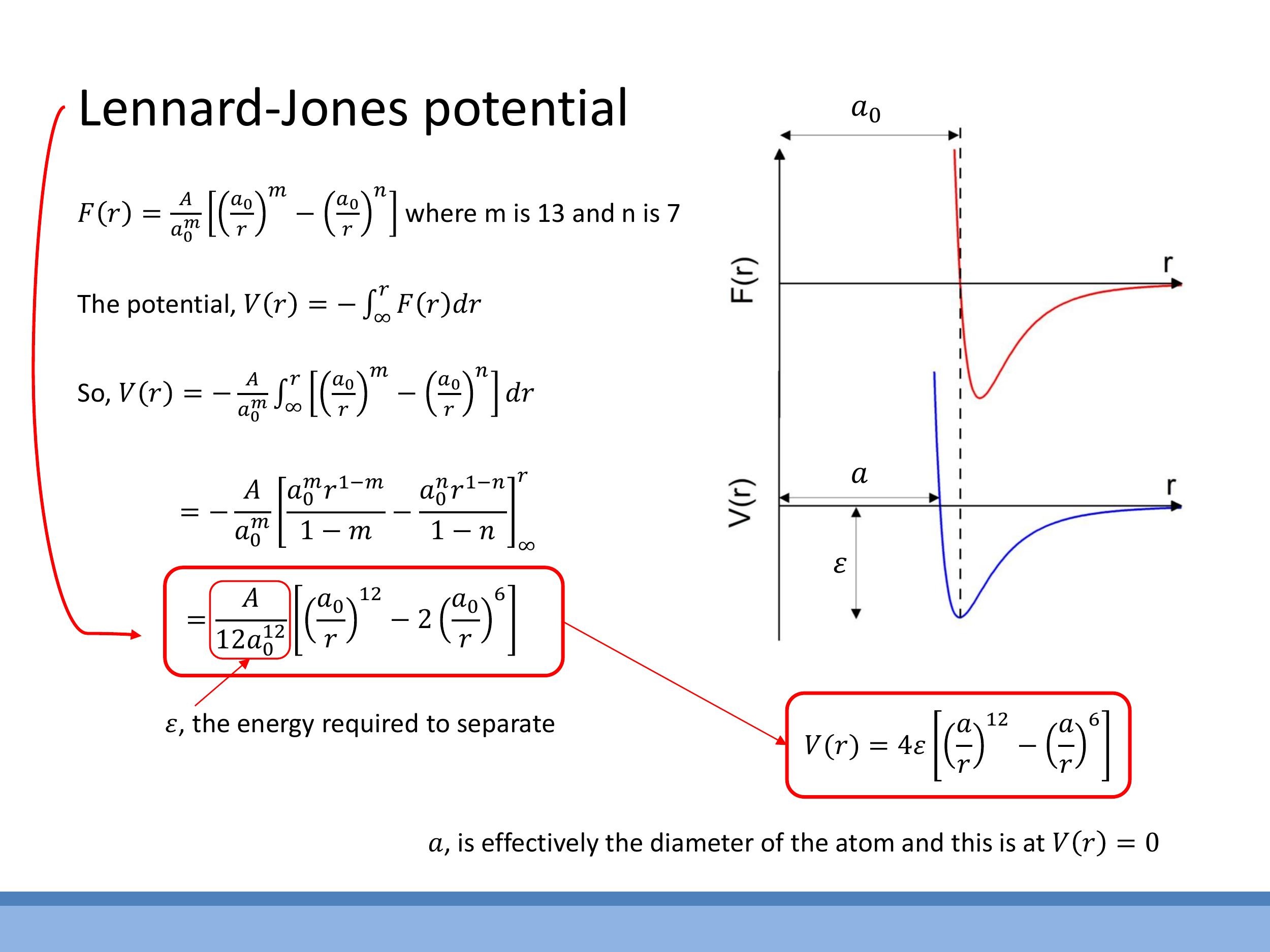

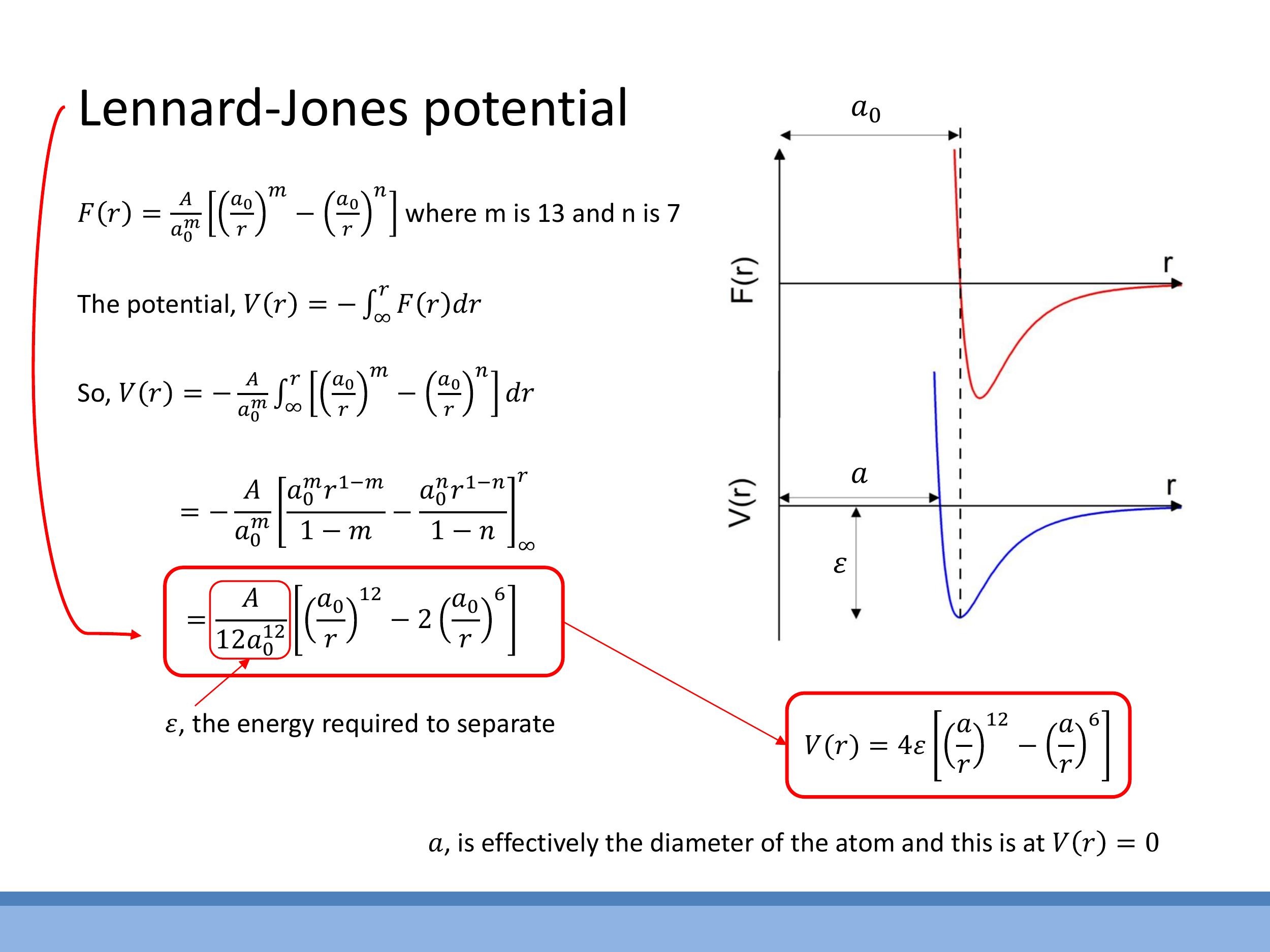

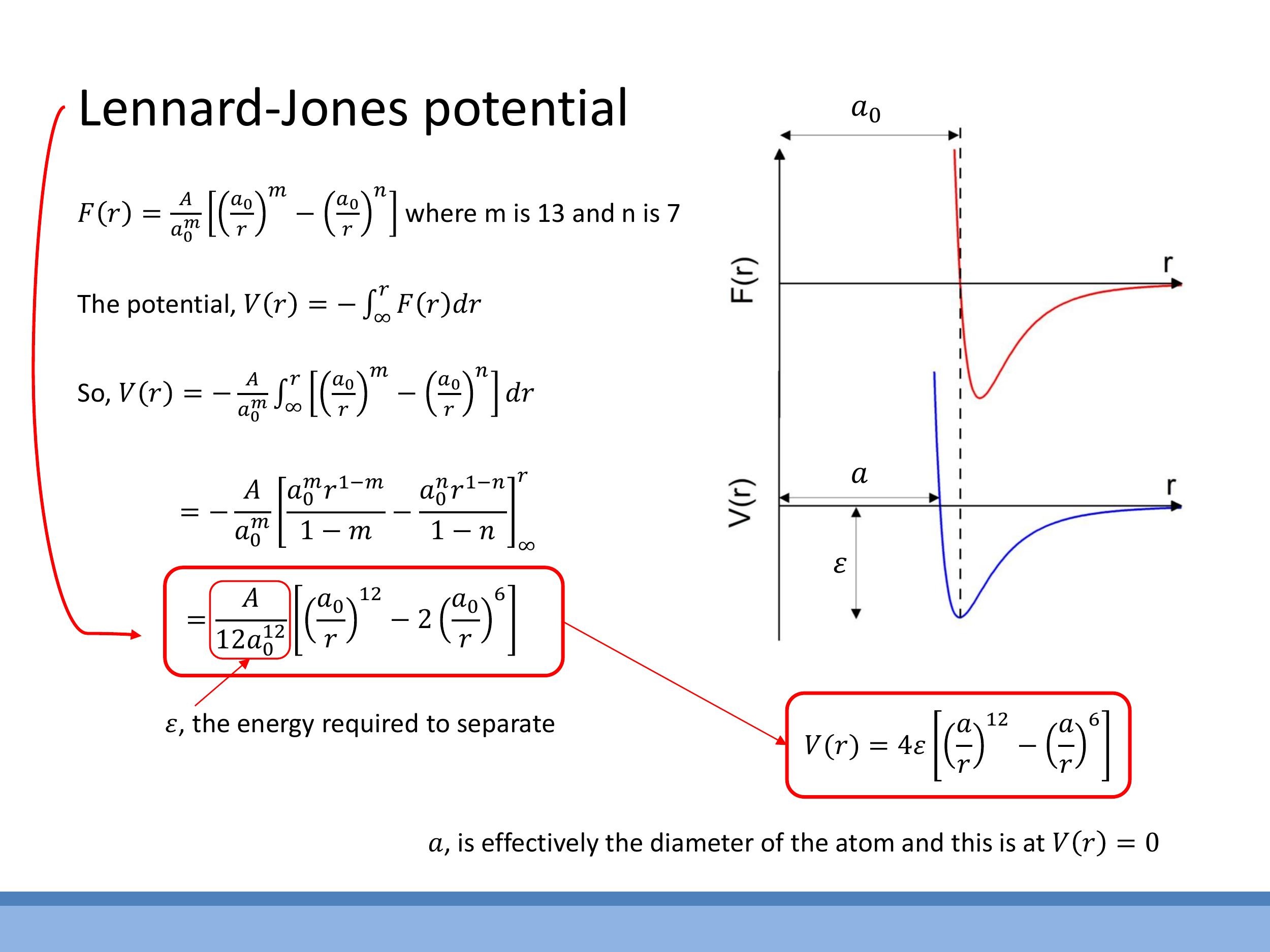

8) From force to potential: arriving at Lennard-Jones

The potential energy $V(r)$ of the interatomic interaction can be derived by integrating the force $F(r)$ with respect to distance, with the convention that $V(\infty) = 0$:

$$

V(r) = -\int F(r) \, dr

$$

If we integrate the two-term force model $F(r) = \frac{A}{r^m} - \frac{B}{r^n}$ with the van der Waals-like exponents $m=13$ and $n=7$, and express $B$ in terms of $A$ and $a_0$, we arrive at a potential energy function that resembles the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential. A common form of the LJ potential is:

$$

V(r) = 4\varepsilon \left[ \left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^6 \right]

$$

This equation describes a potential well, which can be interpreted physically:

- $\varepsilon$ (epsilon): This parameter represents the depth of the potential well, which corresponds to the energy required to separate the two atoms from their bound state to an infinite distance (i.e., the bond strength). A deeper well indicates a stronger bond.

- $a$: This parameter represents the distance at which the potential energy $V(r)$ is zero. It is often used as an approximate atomic size parameter in models, indicating the effective "hard sphere" diameter of the atom.

The potential minimum, where the net force is zero ($F(r)=0$), occurs at a distance $r = r_\text{eq} > a$. The shape of this potential curve, with its steep repulsive wall at short distances and a longer, gentler attractive tail, directly reflects the nature of interatomic forces.

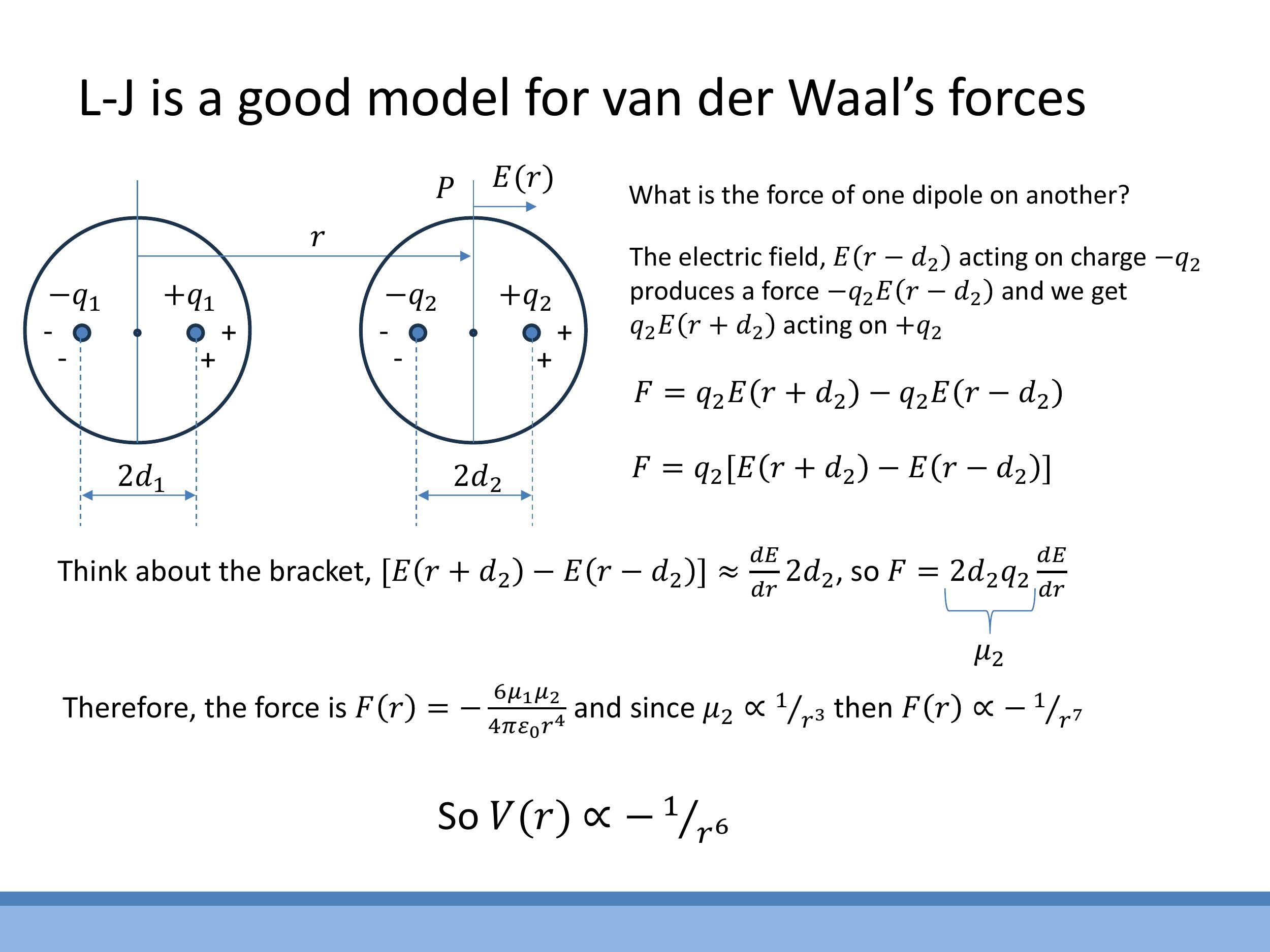

9) Appendix: Why van der Waals attraction scales as 1/r⁶ in V(r)

Side Note: This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

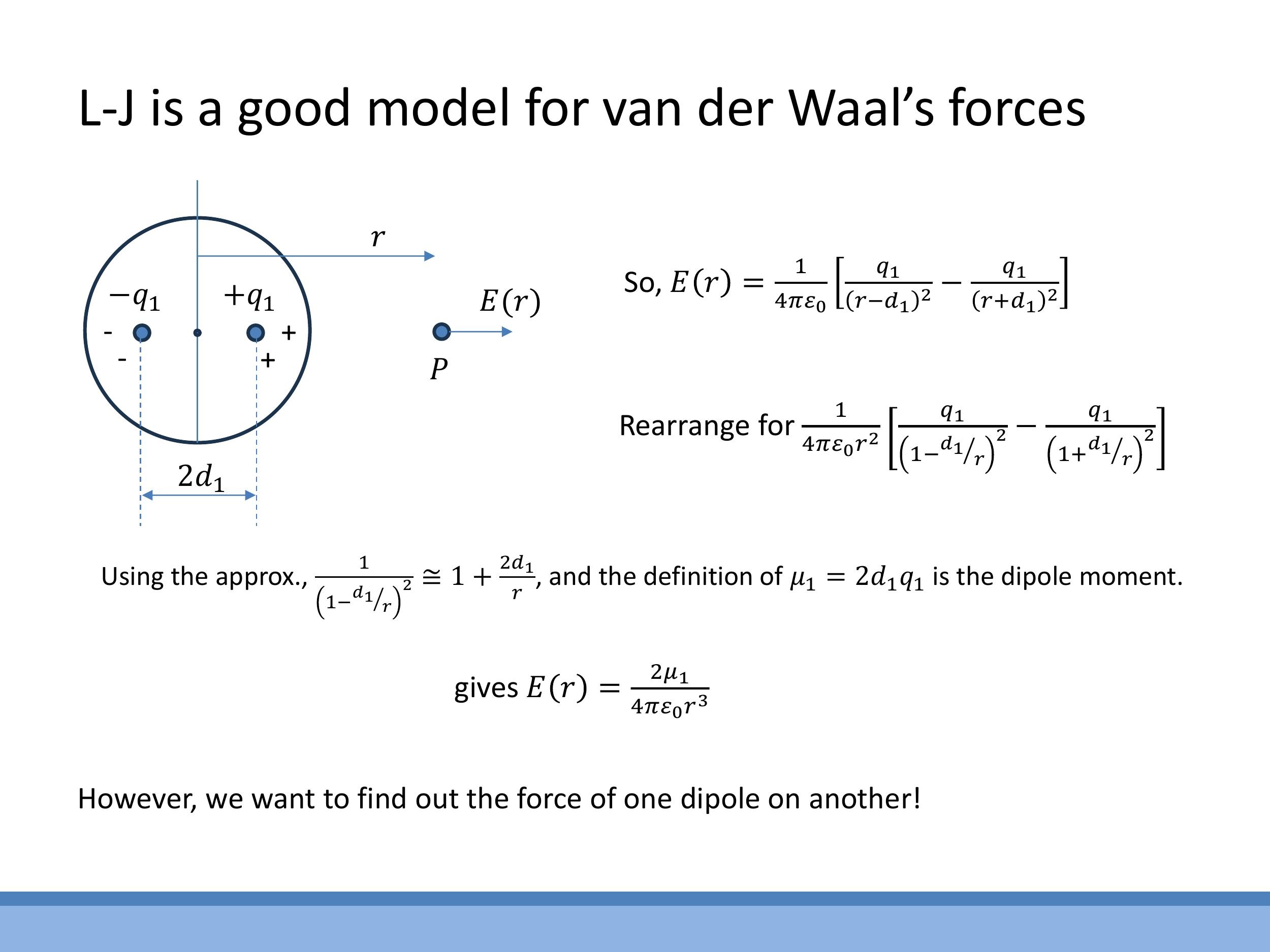

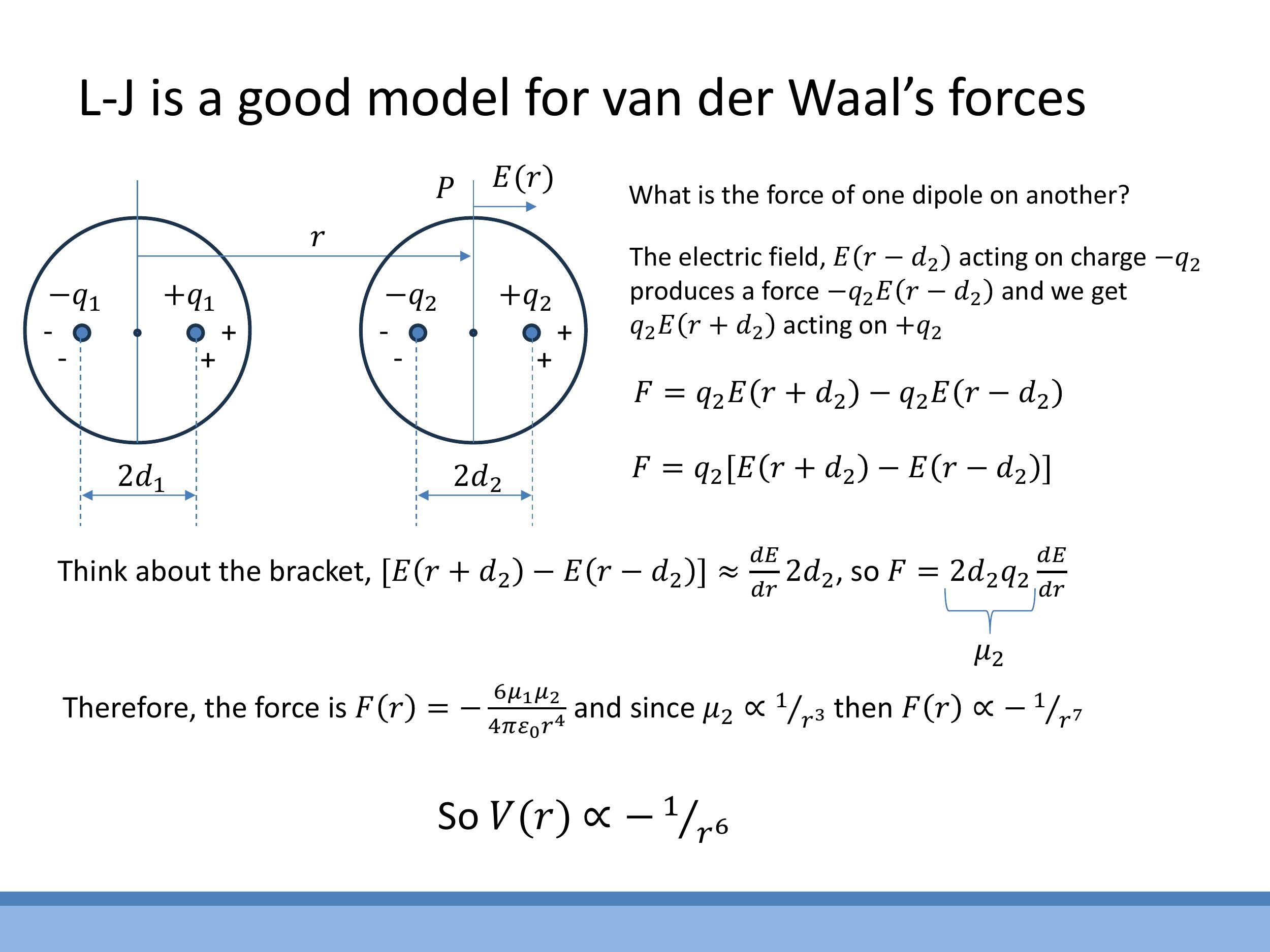

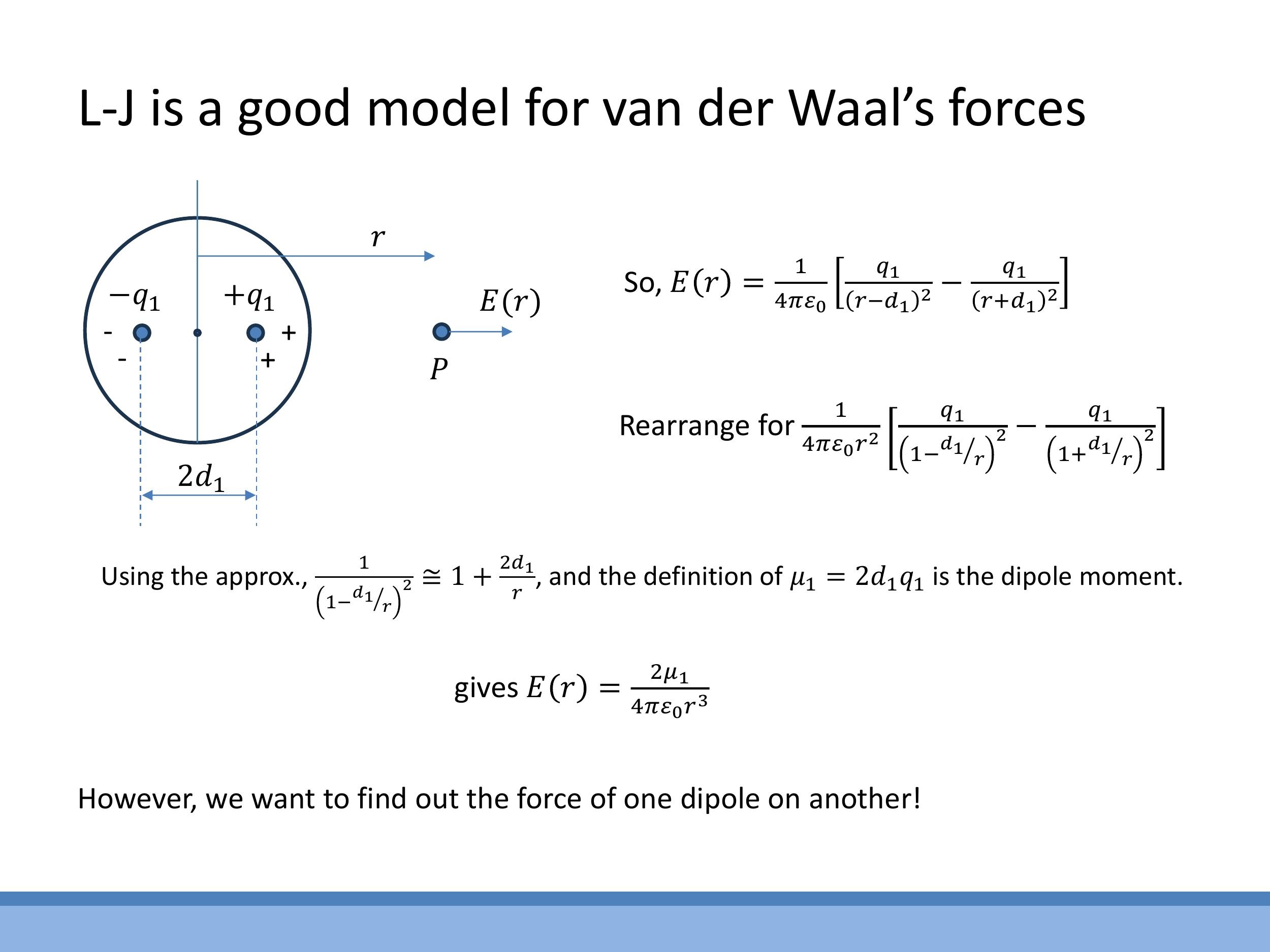

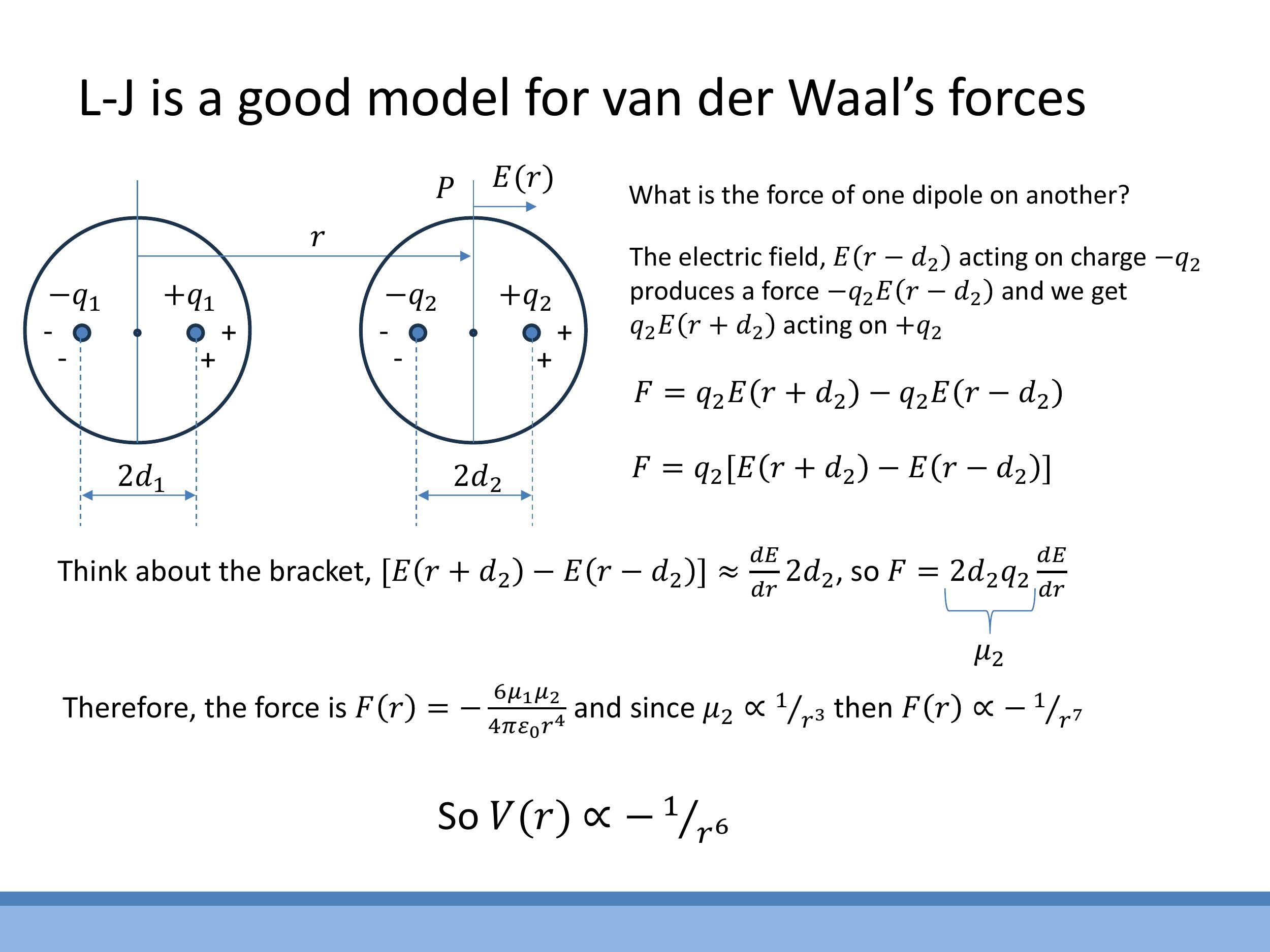

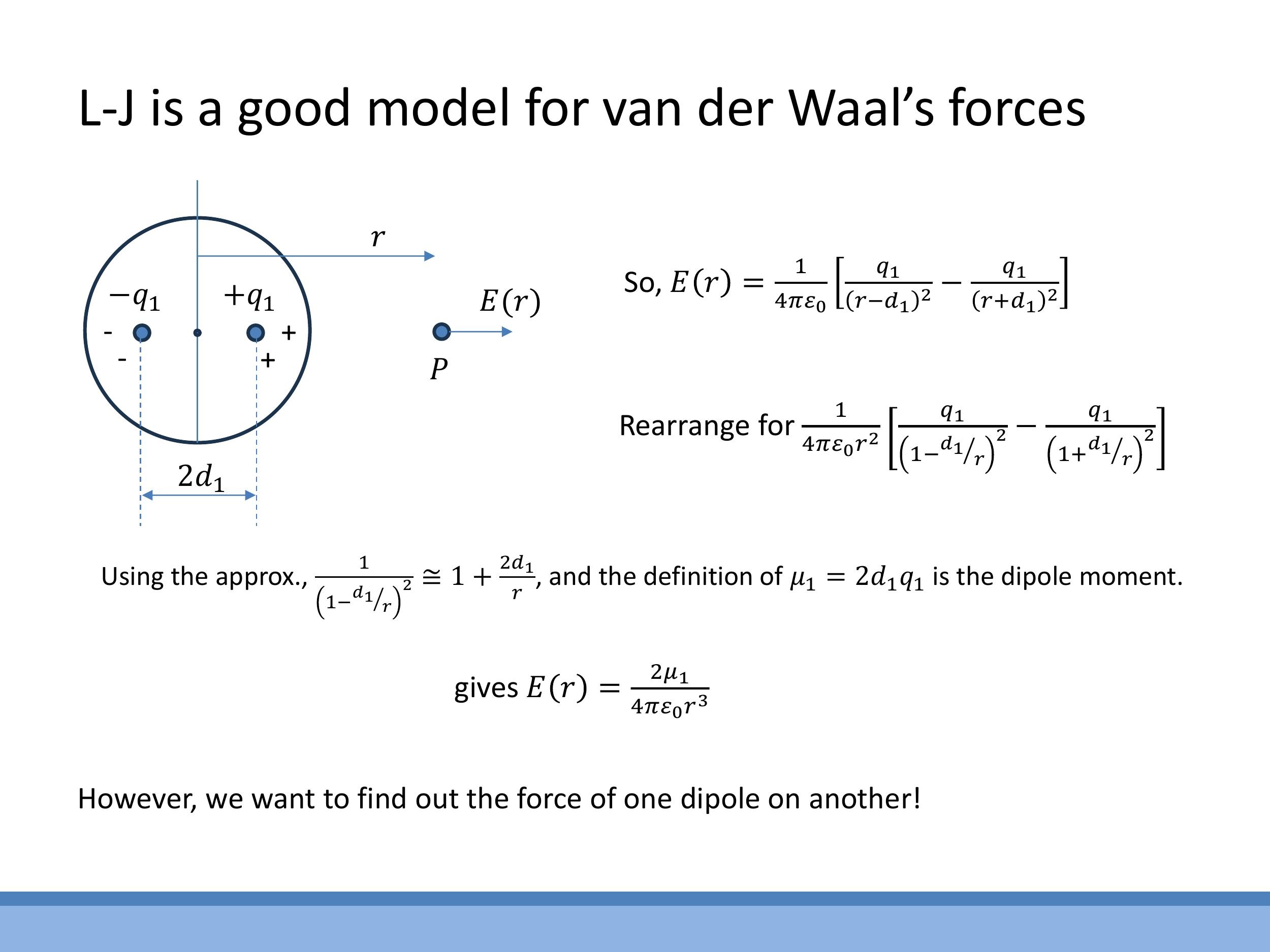

The attractive part of the van der Waals force scales as $1/r^7$ in the force equation, which upon integration gives a $1/r^6$ dependence in the potential energy. This scaling can be outlined through the following argument:

- The electric field $E(r)$ produced by an instantaneous dipole in one atom falls off as $1/r^3$ along its axis (using a binomial approximation for the field of a dipole).

- This electric field then induces a second dipole, $\mu_2$, in a neighbouring neutral atom. The induced dipole moment $\mu_2$ is proportional to the inducing field $E$, so $\mu_2 \propto E \propto 1/r^3$.

- The force $F$ on this induced dipole depends on the gradient of the electric field, $\frac{dE}{dr}$. Since $E \propto 1/r^3$, then $\frac{dE}{dr} \propto 1/r^4$.

- Combining these, the force $F \propto \mu_2 \cdot \frac{dE}{dr} \propto (1/r^3)(1/r^4) = 1/r^7$.

- Finally, integrating the force to find the potential energy, $V(r) = -\int F(r) \, dr $, leads to $ V(r) \propto -1/r^6 $. This derivation provides the theoretical basis for the $ r^{-6}$ attractive term in the Lennard-Jones potential.

Key takeaways

Stable forms of matter, like liquids and solids, require two competing interatomic interactions: a very steep, short-range repulsive force, primarily due to the Pauli exclusion principle, and a weaker, longer-range attractive force, such as van der Waals dispersion forces.

The electromagnetic force is the fundamental interaction responsible for interatomic bonding. A comparative calculation shows that gravity is negligible, being about $10^{32}$ times weaker than electrostatic forces at the $\text{Ångström}$ scale of atomic separations.

The states of matter (gas, liquid, solid) are best distinguished by physical properties such as compressibility, rigidity, and viscosity, rather than simple density or "regular pattern" rules, which have notable exceptions.

A useful and tractable model for interatomic forces is a two-term power law $F(r) = A/r^m - B/r^n$, where $m > n$ ensures the dominance of short-range repulsion. The equilibrium separation $a_0$ is the distance where the net force is zero.

Near equilibrium, atoms in condensed matter can be approximated as behaving like masses connected by springs. The slope of the force-distance curve at equilibrium gives an effective spring constant, underpinning the understanding of atomic vibrations.

Integrating the two-term force model yields the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential, $V(r) = 4\varepsilon [ (a/r)^{12} - (a/r)^6 ]$. In this potential, $\varepsilon$ represents the depth of the potential well, indicating the bond strength, and $a$ is a distance where the potential crosses zero, serving as an approximate atomic size parameter.

The liquefaction of noble gases and the observed increase in their boiling points down the periodic group are explained by van der Waals forces, which arise from temporary, induced dipoles in the electron clouds of these otherwise inert atoms.

## Lecture 2: Interatomic Forces (part 1)

### 0) Orientation and learning outcomes

This course builds on the foundation of Lecture 1 by shifting our focus from individual particles to the collective behaviour of many-body systems. Our aim is to develop an atomic-level understanding of why matter exists in solid, liquid, and gaseous states, and eventually, to connect this microscopic picture to the principles of thermodynamics in later lectures.

A note on course materials: any content marked as an "Appendix" in these notes or the lecture slides is provided for your interest only and will not be included in examinations.

By the end of this lecture, you should be able to:

* Describe the physical properties that distinguish solids, liquids, and gases, such as compressibility, rigidity, and viscosity.

* Identify the main forces acting between atoms at short ranges, recognise different bond types, and understand their typical energy magnitudes.

* Sketch qualitative force-distance curves and pinpoint the equilibrium separation distance between atoms.

* Derive the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential from a two-term power law model for interatomic forces.

* Utilise Lennard-Jones-like potentials to determine equilibrium distances and interpret the physical significance of the parameters $\varepsilon$ (well depth) and $a$ (distance at which potential is zero), which approximates atomic size.

This lecture will explain why matter holds together and what determines the characteristic distances between atoms in condensed phases.

### 1) Why both attraction and repulsion must exist

The existence of solids and liquids in our everyday lives, such as tables and sofas, provides intuitive evidence that atoms must attract each other. Without an attractive force, matter would not condense into these stable forms.

However, if attraction were the only force at play, all matter would simply collapse into itself. The fact that matter maintains stable, finite volumes and structures implies the presence of a counteracting, short-range repulsive force. This balance between attraction and repulsion is crucial for the stability of matter.

The primary origin of this strong, short-range repulsion is a quantum mechanical effect described by the Pauli exclusion principle. This principle states that no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state. As atoms approach each other, their electron wavefunctions begin to overlap. To prevent this overlap, a very steep and powerful repulsive force arises, pushing the atoms apart. While Coulomb repulsion between the positively charged nuclei also exists, the Pauli exclusion principle is the dominant mechanism for short-range repulsion at typical interatomic distances.

We can visualise this balance of forces with a simple analogy: imagine a set of "inverter magnets" where you have a weak, long-range attraction and a strong, short-range repulsion. If you try to push them too close, they strongly resist, but if you pull them too far apart, they weakly attract. This creates a stable "sweet spot" separation, and if displaced, they "snap back" to this equilibrium distance. This demonstration helps build intuition for the stable interatomic separations observed in real materials.

### 2) States of matter: beyond the GCSE table

Simplified definitions of the states of matter, often encountered at GCSE level, can be misleading. For instance, the generalisation that solids are always denser than liquids, which are denser than gases, has exceptions. Ice is less dense than liquid water, and elements like silicon and germanium also exhibit this anomalous behaviour. Similarly, defining a solid by a "regular pattern" (i.e., being crystalline) isn't universally true, as amorphous solids like glass, as well as polymers and plastics, are solids that lack a regular, periodic atomic structure.

A more robust physical characterisation of the states of matter relies on properties like compressibility, rigidity, and viscosity, along with a microscopic understanding of particle motion:

* **Gas:** Gases are highly compressible, exhibit low rigidity, and have low viscosity. Microscopically, their particles are far apart and move randomly at high velocities. For example, nitrogen molecules in room-temperature air (around $20\,^\circ\text{C}$) have a root mean square speed of approximately $500\,\text{m s}^{-1}$, which is roughly $1000\,\text{mph}$. This high speed contributes to their large mean free path and low density.

* **Liquid:** Liquids have very low compressibility, similar to solids, but possess no rigidity, meaning they flow and take the shape of their container. Their viscosity is typically about $100$ times greater than that of a gas. At a microscopic level, liquid molecules are much closer together than in a gas, allowing them to move past one another. Their motion is a mixture of translational and vibrational components.

* **Solid:** Solids are rigid and have low compressibility. Their atoms vibrate about fixed positions within a structure, with negligible translational motion. This fixed arrangement gives solids their characteristic shape and resistance to deformation.

*Side Note:* While this course focuses on solids, liquids, and gases, it's worth noting that these make up less than $1\%$ of the ordinary matter in the observable universe. The vast majority of ordinary matter exists as plasma, such as in stars and nebulae.

### 3) Which fundamental force binds atoms? Range and scale

To understand which fundamental force is responsible for interatomic bonding, we first consider their typical ranges:

* **Strong force:** Approximately $10^{-15}\,\text{m}$ (a femtometre or Fermi).

* **Weak force:** Approximately $10^{-18}\,\text{m}$.

* **Electromagnetic force:** Infinite range.

* **Gravity:** Infinite range.

Given that typical interatomic separations are around $10^{-10}\,\text{m}$, which is $1\,\text{Ångström}$ ($\text{Å}$), the strong and weak nuclear forces are too short-ranged to play a direct role in bonding atoms together.

> **⚠️ Exam Alert!** The lecturer explicitly stated that knowing the $\text{Ångström}$ scale ($10^{-10}\,\text{m}$) is very useful for multiple-choice questions in December and longer questions in the summer exam. Having an idea of sensible atomic distances will help you determine if your calculations are on the right track.

This leaves us with electromagnetism and gravity. To determine which dominates, let's perform an order-of-magnitude test. Consider two hypothetical atoms, each with a mass of $100\,\text{u}$ (atomic mass units) and charges of $\pm e$ (for an ionic bond), separated by a distance $r = 1.5\,\text{Å} = 1.5 \times 10^{-10}\,\text{m}$.

We can calculate their gravitational and electrostatic potential energies:

* Gravitational potential energy: $U_g = -\frac{G m_1 m_2}{r}$

* Electrostatic potential energy: $U_e = \frac{q_1 q_2}{4\pi\varepsilon_0 r}$

Using the relevant constants ($G \approx 6.67 \times 10^{-11}\,\text{N m}^2 \text{kg}^{-2}$, $1/(4\pi\varepsilon_0) \approx 8.99 \times 10^9\,\text{N m}^2 \text{C}^{-2}$), and converting the results to electron volts ($\text{eV}$) for easier comparison with typical bond energies:

* $U_g \approx 7.65 \times 10^{-32}\,\text{eV}$

* $U_e \approx 9.6\,\text{eV}$

This calculation clearly shows that the electrostatic force is approximately $10^{32}$ times stronger than the gravitational force at interatomic distances. Therefore, electromagnetism is the only force that significantly contributes to interatomic bonding.

### 4) Bond types as manifestations of electrostatics

All interatomic bonds are manifestations of electrostatic interactions, though they differ in how electrons are distributed or transferred.

* **Ionic bonds** form when electrons are completely transferred from one atom to another, creating oppositely charged ions (cations and anions) that are then strongly attracted by the Coulomb force. Sodium chloride ($\text{NaCl}$) is a classic example.

* **Covalent bonds** involve the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. This sharing creates strong, often directional bonds that hold atoms together.

* **Metallic bonds** are characterised by a "sea" of delocalised valence electrons that are shared among a lattice of positive ion cores. This results in strong, non-directional bonding that accounts for the characteristic properties of metals.

Beyond these strong bonds, there are also weaker **polar interactions**:

* **Hydrogen bonds** are a specific type of dipole-dipole interaction that occurs when hydrogen is bonded to a highly electronegative atom (like oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine), creating a permanent dipole which can then attract other polar molecules.

* **Van der Waals forces**, also known as London dispersion forces, arise from temporary, induced dipoles. These are typically weaker than hydrogen bonds and are discussed in more detail below.

### 5) Van der Waals forces and noble gases

The existence of van der Waals forces helps us solve a puzzle: noble gases like helium ($\text{He}$), neon ($\text{Ne}$), and argon ($\text{Ar}$) are electrically neutral and have full electron shells, meaning they are chemically inert. Yet, when cooled sufficiently, they liquefy. What force holds these atoms together?

The mechanism behind this is called London dispersion. Although noble gas atoms are neutral on average, at any given instant, the electrons in an atom's cloud might be momentarily unevenly distributed, creating a transient, instantaneous dipole. This temporary dipole can then induce a corresponding dipole in a neighbouring atom, leading to a weak, short-lived attractive force between them. These induced-dipole interactions are responsible for the liquefaction of noble gases.

Empirical data supports this mechanism. As you move down the noble gas group from helium to xenon ($\text{Xe}$), the atoms become larger and have more electrons, making their electron clouds more polarisable (i.e., easier to distort and form temporary dipoles). This increased polarisability leads to stronger London dispersion forces, which in turn require more energy to overcome, resulting in higher boiling points. The boiling points of noble gases increase significantly down the group, consistent with the strengthening of these dispersion forces.

### 6) A simple interatomic force model: two-term power law

To quantitatively model interatomic forces, we can represent the net force $F(r)$ between two atoms as the sum of a short-range repulsive term and a longer-range attractive term. A common approach uses a two-term power law:

$$ F(r) = \frac{A}{r^m} - \frac{B}{r^n} $$

Here, the $\frac{A}{r^m}$ term represents the repulsion, and the $-\frac{B}{r^n}$ term represents the attraction (the negative sign indicates an attractive force in the direction of decreasing $r$). For this model to prevent matter from collapsing, the repulsive force must be much steeper and shorter-ranged than the attractive force, meaning the exponent $m$ must be greater than $n$. At very short distances, the repulsive force (due to Pauli exclusion) dominates, rising sharply. At longer distances, the attractive force (e.g., van der Waals) is stronger, creating a shallow well before the force eventually approaches zero as $r \to \infty$.

The equilibrium separation distance, denoted as $a_0$, is the "sweet spot" where the attractive and repulsive forces perfectly balance, meaning $F(a_0) = 0$. From this condition, we can relate the coefficients $A$ and $B$:

$$ B = A a_0^{n-m} $$

Substituting this back into the force equation allows us to express $F(r)$ in terms of $a_0$. For van der Waals systems, typical empirical exponents are $m \approx 13$ for the repulsive term and $n \approx 7$ for the attractive term.

### 7) Near equilibrium: atoms behave like masses on springs (SHM)

For small displacements ($\delta r$) around the equilibrium separation $a_0$, the interatomic force curve can be approximated as linear. This is analogous to Hooke's law for a spring. If an atom is slightly displaced from $a_0$, a restoring force $\delta F$ acts to bring it back to equilibrium. This restoring force is given by the gradient of the force curve at $a_0$:

$$ \delta F = \left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right)_{r=a_0} \cdot \delta r $$

By comparing this to Hooke's law, $F = -k x$, we can identify an effective spring constant $k_\text{eff} = -\left(\frac{dF}{dr}\right)_{a_0}$. This model implies that atoms in a solid or liquid vibrate about their equilibrium positions, much like masses attached to springs.

This "atoms-as-springs" picture is fundamental to understanding phenomena like thermal conductivity in non-metals. In these materials, heat is primarily transported by lattice vibrations, known as phonons, which are quantised packets of vibrational energy moving through the material.

### 8) From force to potential: arriving at Lennard-Jones

The potential energy $V(r)$ of the interatomic interaction can be derived by integrating the force $F(r)$ with respect to distance, with the convention that $V(\infty) = 0$:

$$ V(r) = -\int F(r) \, dr $$

If we integrate the two-term force model $F(r) = \frac{A}{r^m} - \frac{B}{r^n}$ with the van der Waals-like exponents $m=13$ and $n=7$, and express $B$ in terms of $A$ and $a_0$, we arrive at a potential energy function that resembles the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential. A common form of the LJ potential is:

$$ V(r) = 4\varepsilon \left[ \left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^6 \right] $$

This equation describes a potential well, which can be interpreted physically:

* **$\varepsilon$ (epsilon):** This parameter represents the depth of the potential well, which corresponds to the energy required to separate the two atoms from their bound state to an infinite distance (i.e., the bond strength). A deeper well indicates a stronger bond.

* **$a$:** This parameter represents the distance at which the potential energy $V(r)$ is zero. It is often used as an approximate atomic size parameter in models, indicating the effective "hard sphere" diameter of the atom.

The potential minimum, where the net force is zero ($F(r)=0$), occurs at a distance $r = r_\text{eq} > a$. The shape of this potential curve, with its steep repulsive wall at short distances and a longer, gentler attractive tail, directly reflects the nature of interatomic forces.

### 9) Appendix: Why van der Waals attraction scales as 1/r⁶ in V(r)

*Side Note:* This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

The attractive part of the van der Waals force scales as $1/r^7$ in the force equation, which upon integration gives a $1/r^6$ dependence in the potential energy. This scaling can be outlined through the following argument:

1. The electric field $E(r)$ produced by an instantaneous dipole in one atom falls off as $1/r^3$ along its axis (using a binomial approximation for the field of a dipole).

2. This electric field then induces a second dipole, $\mu_2$, in a neighbouring neutral atom. The induced dipole moment $\mu_2$ is proportional to the inducing field $E$, so $\mu_2 \propto E \propto 1/r^3$.

3. The force $F$ on this induced dipole depends on the gradient of the electric field, $\frac{dE}{dr}$. Since $E \propto 1/r^3$, then $\frac{dE}{dr} \propto 1/r^4$.

4. Combining these, the force $F \propto \mu_2 \cdot \frac{dE}{dr} \propto (1/r^3)(1/r^4) = 1/r^7$.

5. Finally, integrating the force to find the potential energy, $V(r) = -\int F(r) \, dr$, leads to $V(r) \propto -1/r^6$. This derivation provides the theoretical basis for the $r^{-6}$ attractive term in the Lennard-Jones potential.

## Key takeaways

Stable forms of matter, like liquids and solids, require two competing interatomic interactions: a very steep, short-range repulsive force, primarily due to the Pauli exclusion principle, and a weaker, longer-range attractive force, such as van der Waals dispersion forces.

The electromagnetic force is the fundamental interaction responsible for interatomic bonding. A comparative calculation shows that gravity is negligible, being about $10^{32}$ times weaker than electrostatic forces at the $\text{Ångström}$ scale of atomic separations.

The states of matter (gas, liquid, solid) are best distinguished by physical properties such as compressibility, rigidity, and viscosity, rather than simple density or "regular pattern" rules, which have notable exceptions.

A useful and tractable model for interatomic forces is a two-term power law $F(r) = A/r^m - B/r^n$, where $m > n$ ensures the dominance of short-range repulsion. The equilibrium separation $a_0$ is the distance where the net force is zero.

Near equilibrium, atoms in condensed matter can be approximated as behaving like masses connected by springs. The slope of the force-distance curve at equilibrium gives an effective spring constant, underpinning the understanding of atomic vibrations.

Integrating the two-term force model yields the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential, $V(r) = 4\varepsilon [ (a/r)^{12} - (a/r)^6 ]$. In this potential, $\varepsilon$ represents the depth of the potential well, indicating the bond strength, and $a$ is a distance where the potential crosses zero, serving as an approximate atomic size parameter.

The liquefaction of noble gases and the observed increase in their boiling points down the periodic group are explained by van der Waals forces, which arise from temporary, induced dipoles in the electron clouds of these otherwise inert atoms.