Lecture 9: First Law Revisited

This lecture provides a bridge from the discussion of real gases and phase diagrams to the operational application of the First Law of Thermodynamics. The primary goals are to clarify the distinction between state functions and processes, compute the change in internal energy ($\Delta U$) for an ideal gas, and establish the foundational relationships for adiabatic processes. By the end of this session, students will be able to calculate changes in internal energy from heat and work, understand heat capacities and their interdependence, grasp the implications of the Joule free expansion experiment, connect microscopic and macroscopic views of the First Law, and set up the initial conditions for an adiabatic expansion.

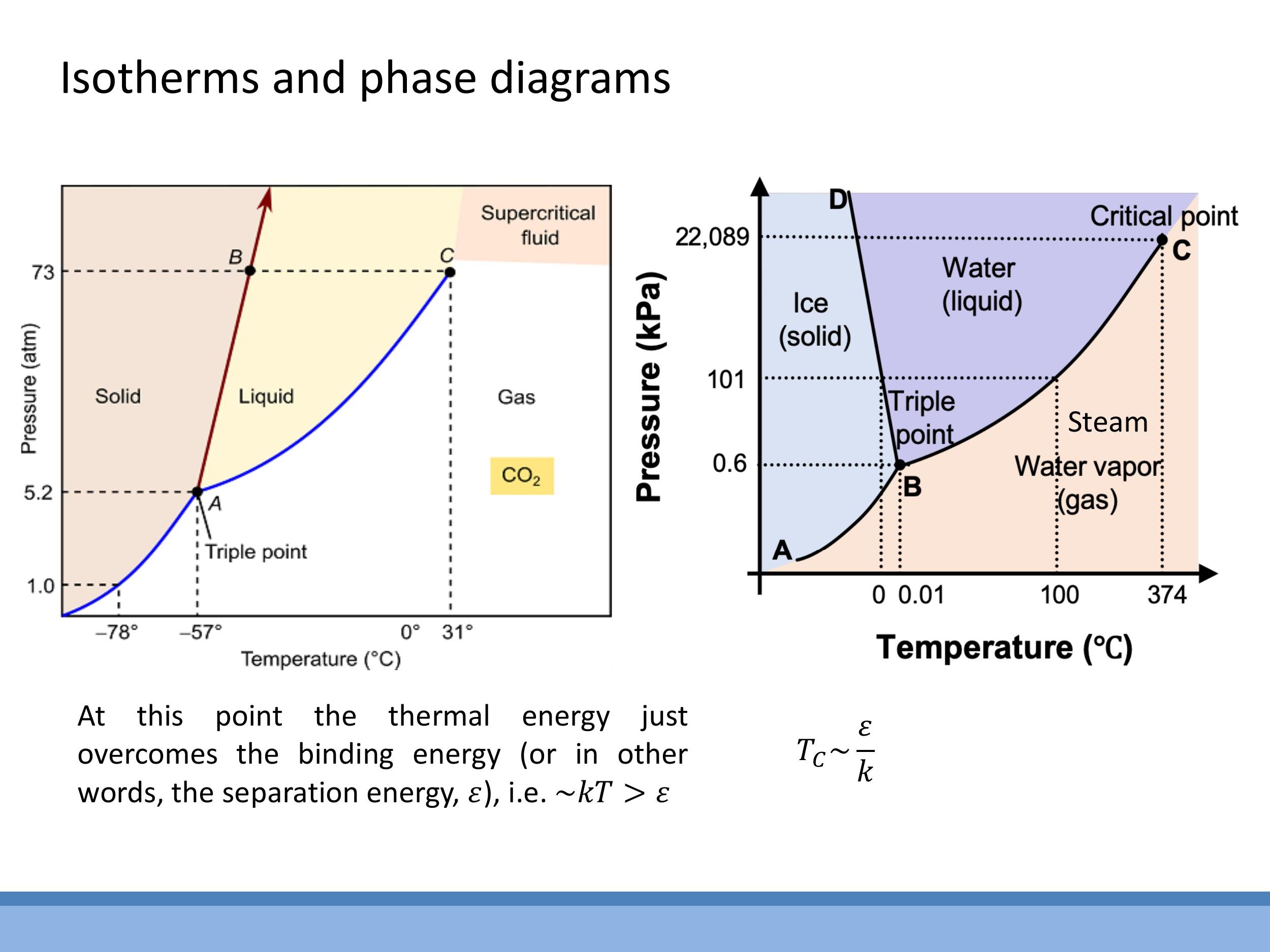

1) Recap: real-gas isotherms, the phase dome, and $T_C \sim \varepsilon/k$

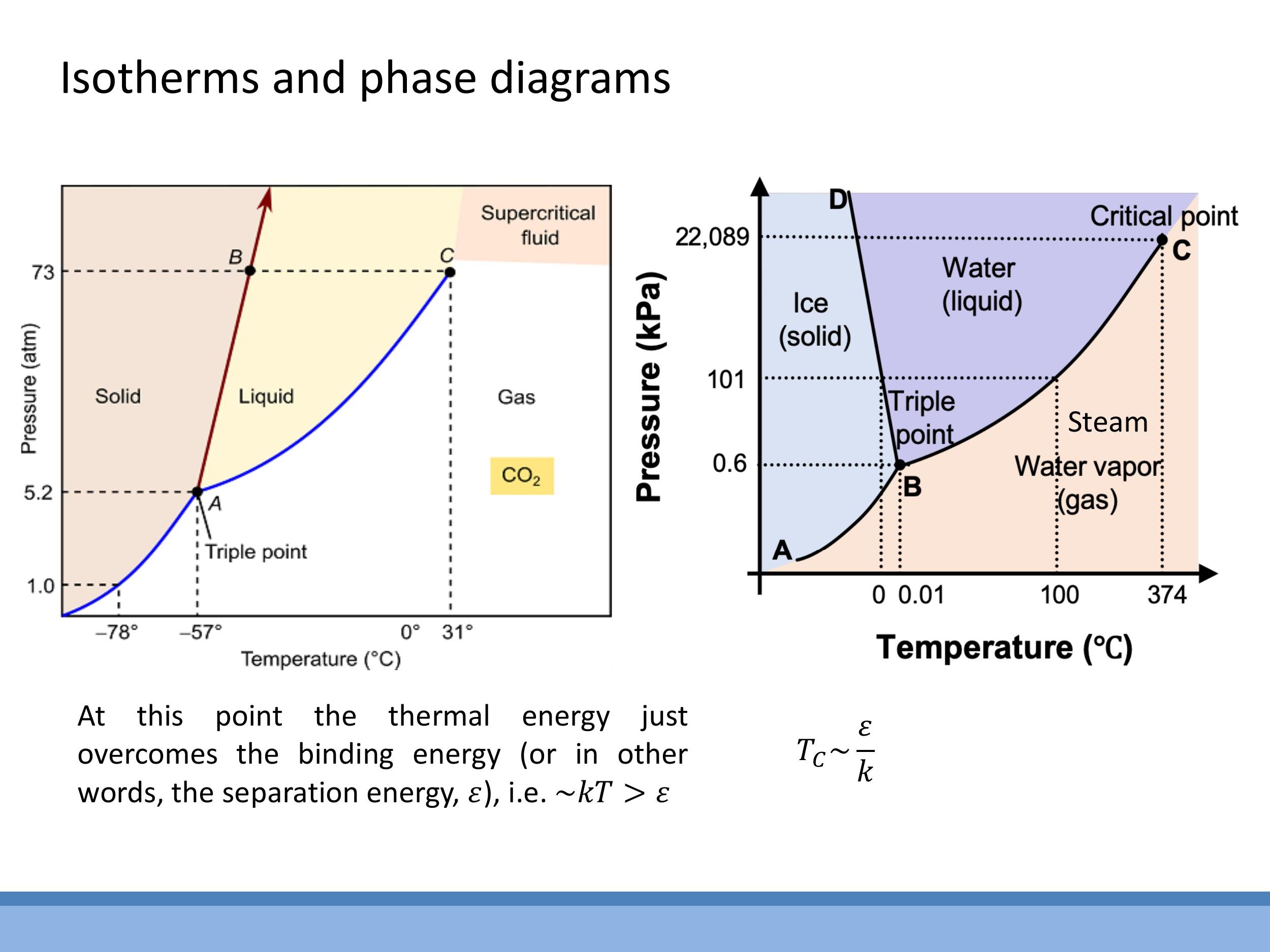

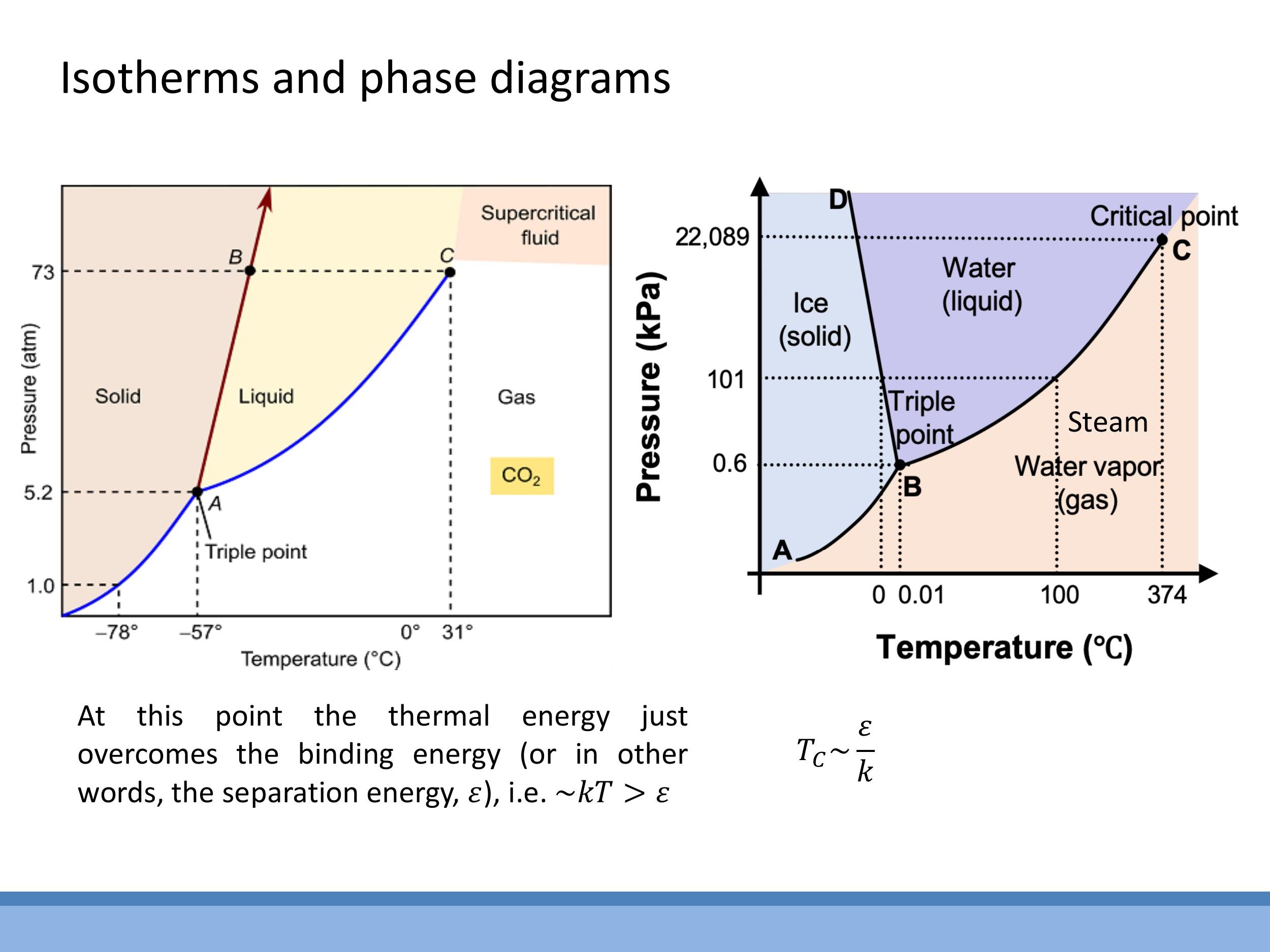

Ideal gases obey the ideal gas law, $PV = RT$, which produces smooth hyperbolic isotherms on a pressure-volume ($P$ - $V$) diagram. However, real gases exhibit deviations at lower temperatures, where intermolecular forces become significant. This leads to the appearance of a "two-phase region" or "dome" in $P$ - $V$ isotherms, representing gas-liquid coexistence, which is resolved physically by the process of condensation. These deviations arise because real gas molecules have finite size, reducing the available volume (addressed by the van der Waals $nb$ term), and experience intermolecular attractions, which reduce the measured wall pressure (addressed by the van der Waals $a/V^2$ term).

The critical isotherm, at a specific critical temperature ($T_C$), marks the boundary above which a gas cannot be liquefied by compression alone; the liquid and gas phases become indistinguishable, forming a supercritical fluid. This critical temperature provides a link between macroscopic behaviour and microscopic energy scales, as the thermal energy $kT_C$ is approximately equal to the intermolecular binding energy $\varepsilon$, leading to the relation $T_C \sim \frac{\varepsilon}{k}$. This allows for estimation of the critical temperature if the bond energy is known. Water exhibits an anomalous phase diagram where the solid-liquid boundary has a negative slope, meaning that increasing pressure can melt ice. This is due to ice being less dense than liquid water, a rare but crucial property.

2) Thermodynamic terms and state functions

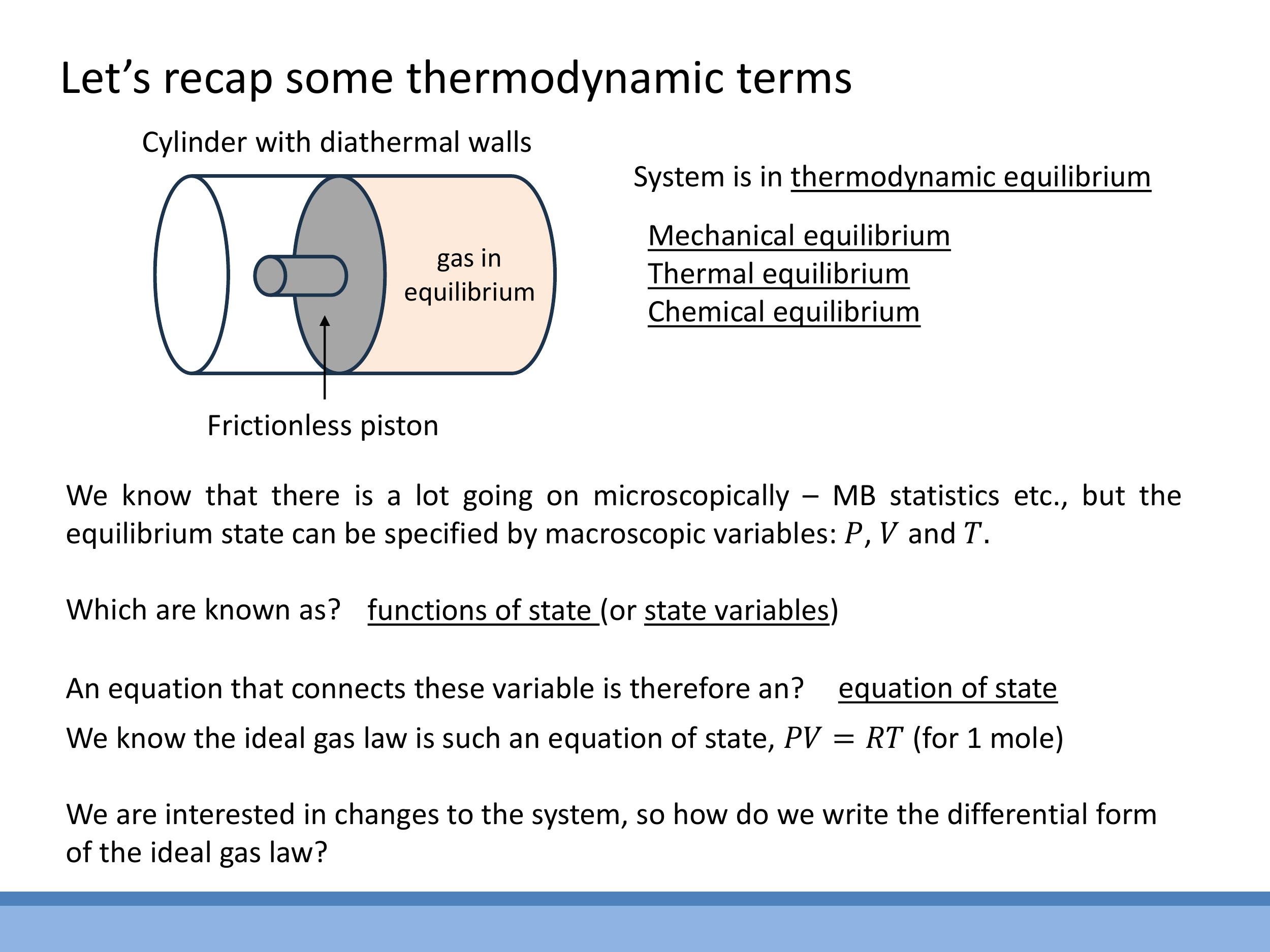

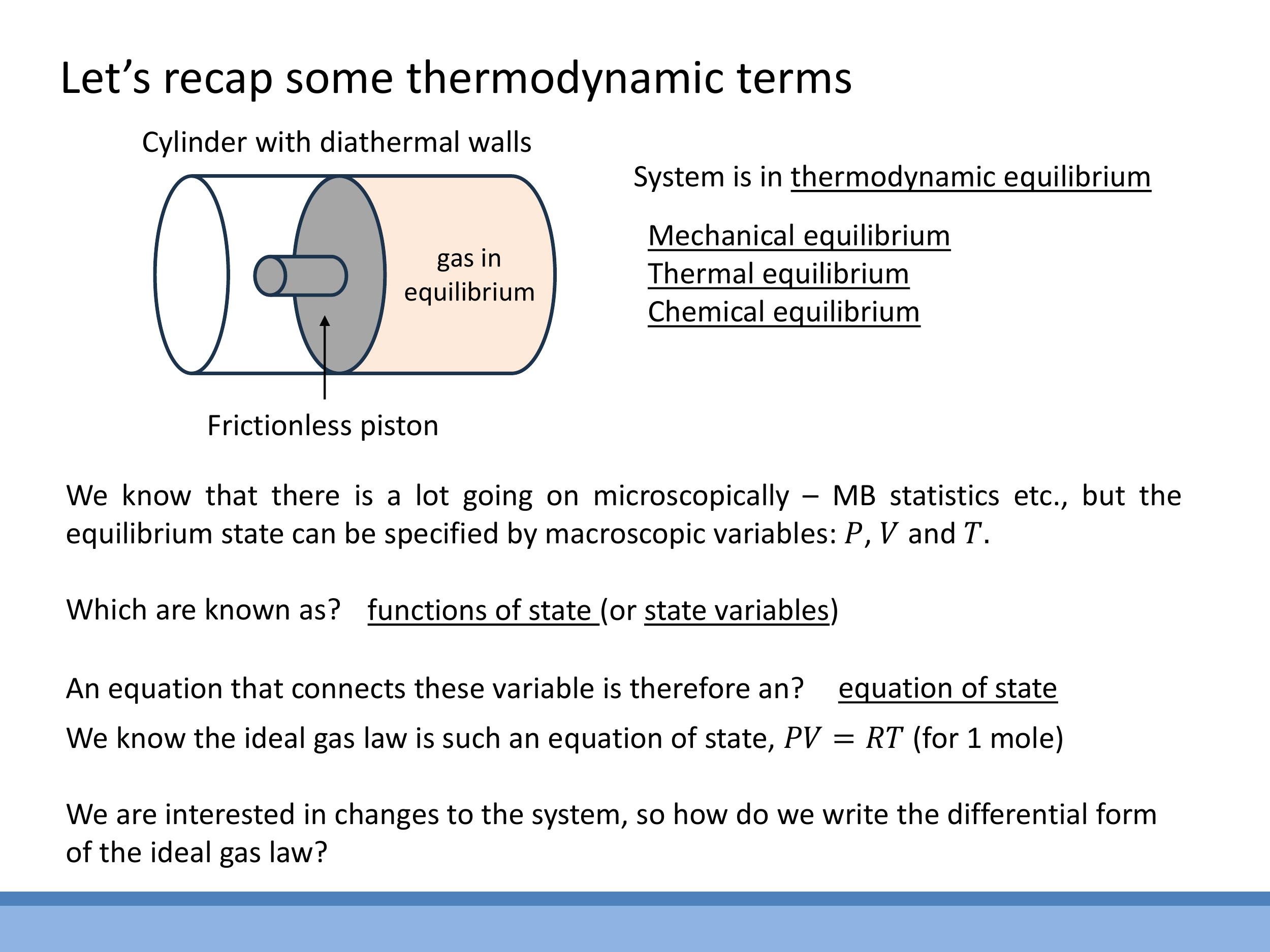

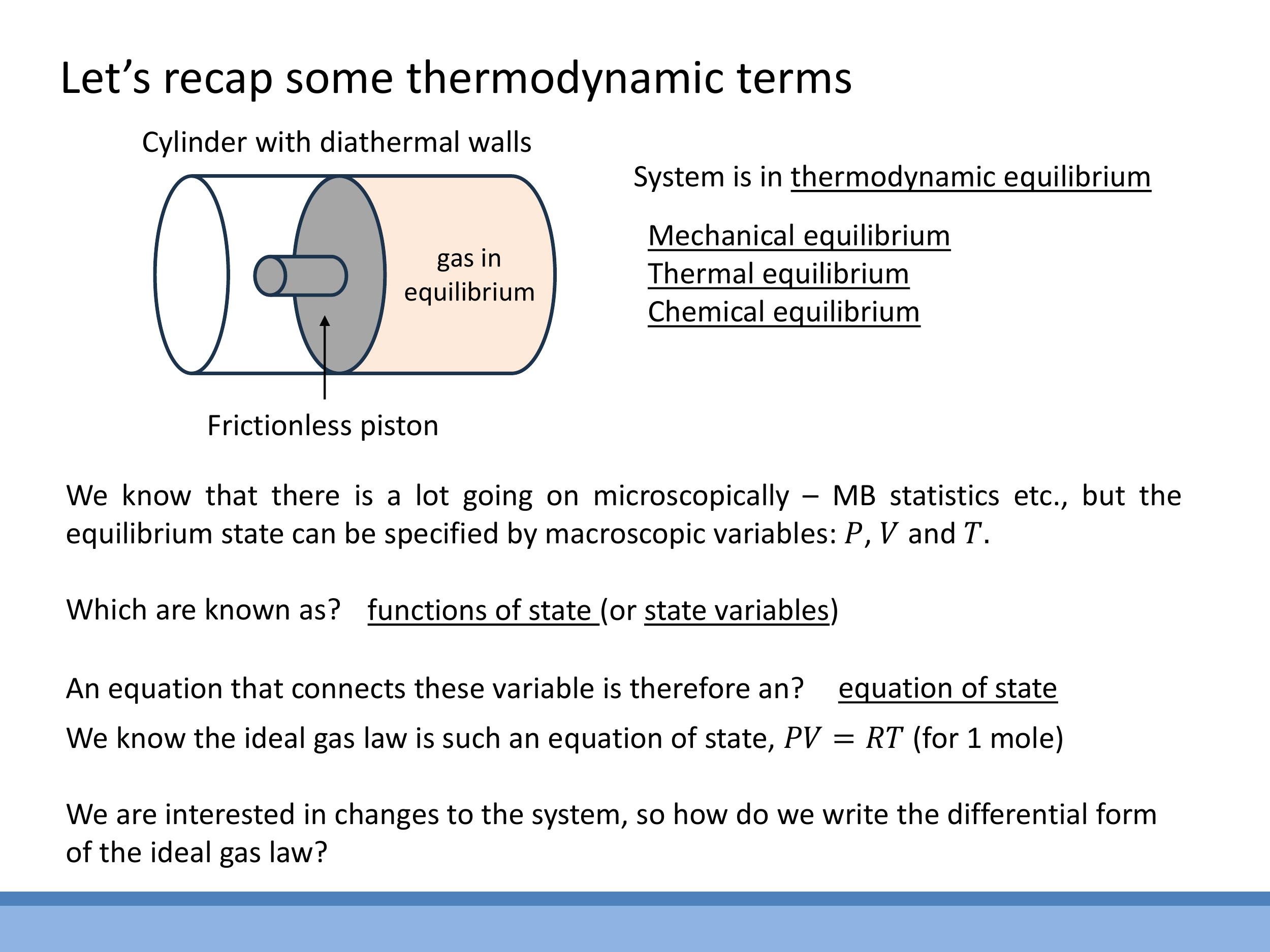

In thermodynamics, a common model system consists of a gas confined within a cylinder by a frictionless piston. The walls of the cylinder can be classified as either diathermal, allowing heat to flow through, or adiabatic, preventing any heat transfer. A system is in thermodynamic equilibrium when its macroscopic properties remain constant, encompassing mechanical equilibrium (no net forces), thermal equilibrium (no net heat flow), and chemical equilibrium (no net change in chemical composition).

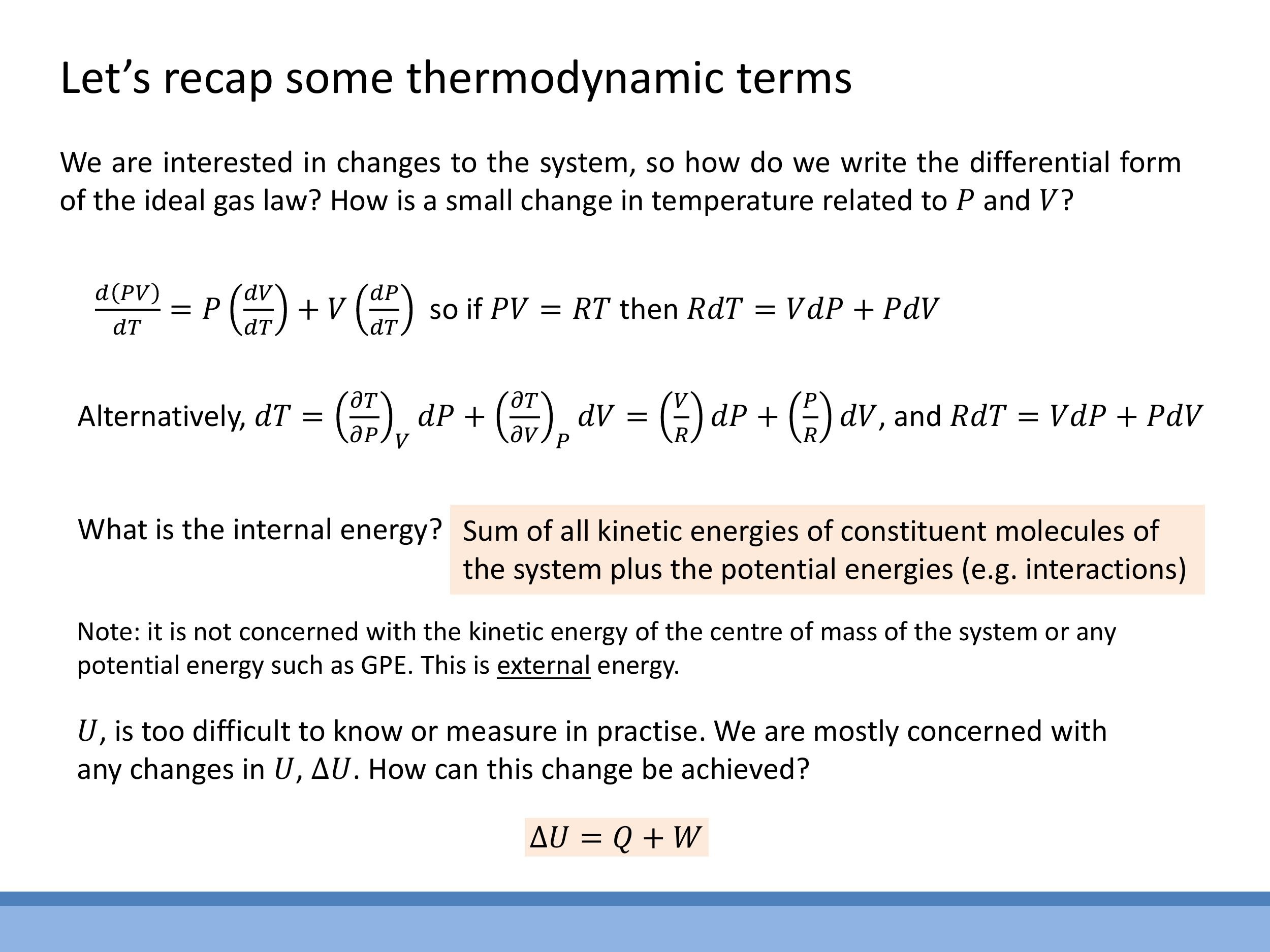

The macroscopic state of a system is defined by state variables such as pressure ($P$), volume ($V$), and temperature ($T$). These are known as state functions because their values depend only on the current state of the system, not on the path taken to reach that state. Any mathematical relationship between these state variables, such as the ideal gas law ($PV = RT$ for one mole), is termed an equation of state.

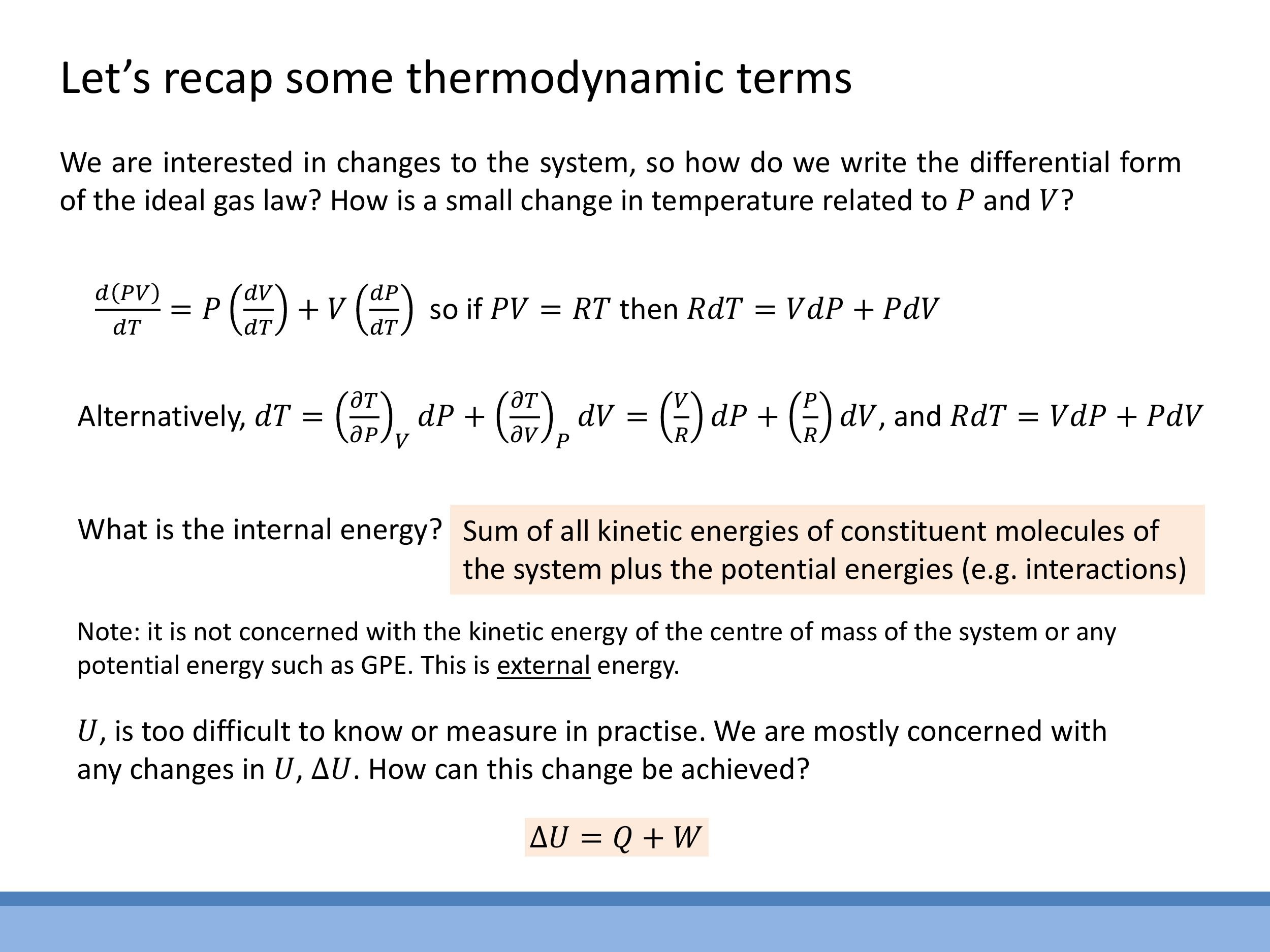

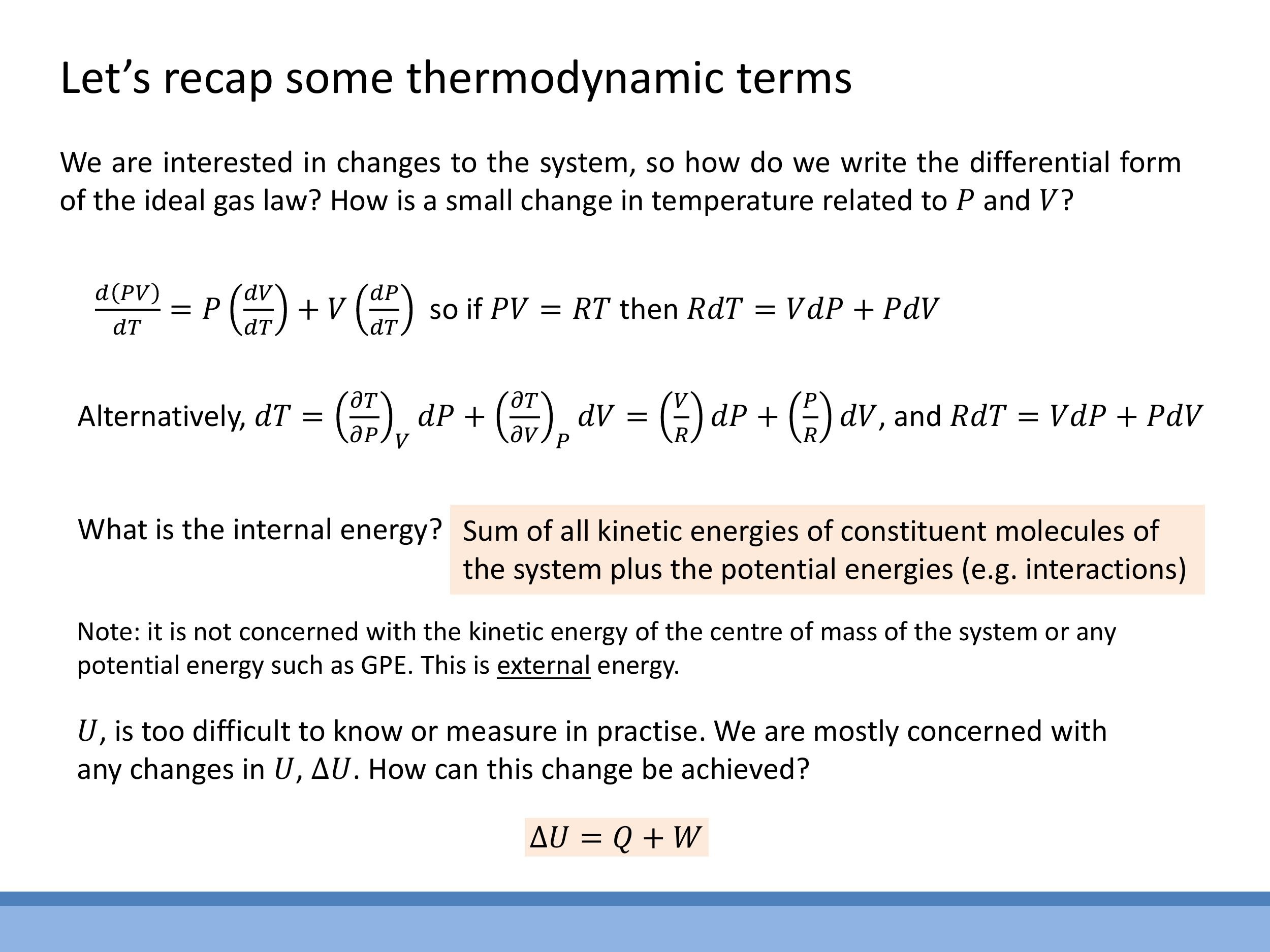

To analyse small changes in a thermodynamic system, the ideal gas law can be expressed in a differential form. Starting with the ideal gas law for one mole, $PV = RT$, and applying the product rule to the left-hand side for an infinitesimal change, $d(PV) = PdV + VdP$. Since $R$ is a constant, the change on the right-hand side is $d(RT) = RdT$. Equating these expressions yields the differential form of the ideal gas law for one mole:

$$

RdT = VdP + PdV

$$

This identity links small changes in temperature ($dT$) to corresponding small changes in pressure ($dP$) and volume ($dV$), serving as a fundamental tool for calculations involving thermodynamic processes. Generalisation to $n$ moles is straightforward by replacing $R$ with $nR$.

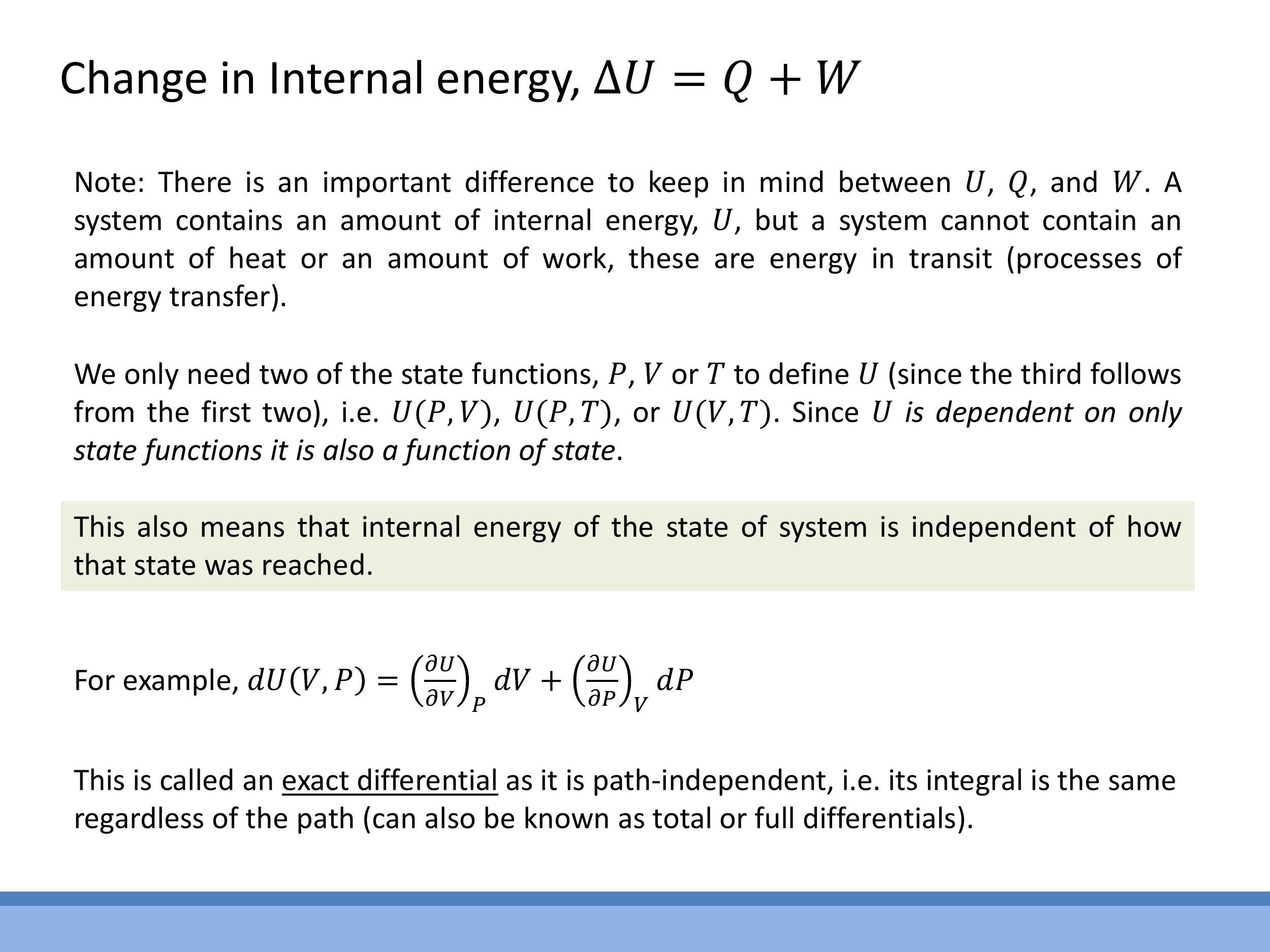

4) Internal energy $U$: what it is and what we can measure

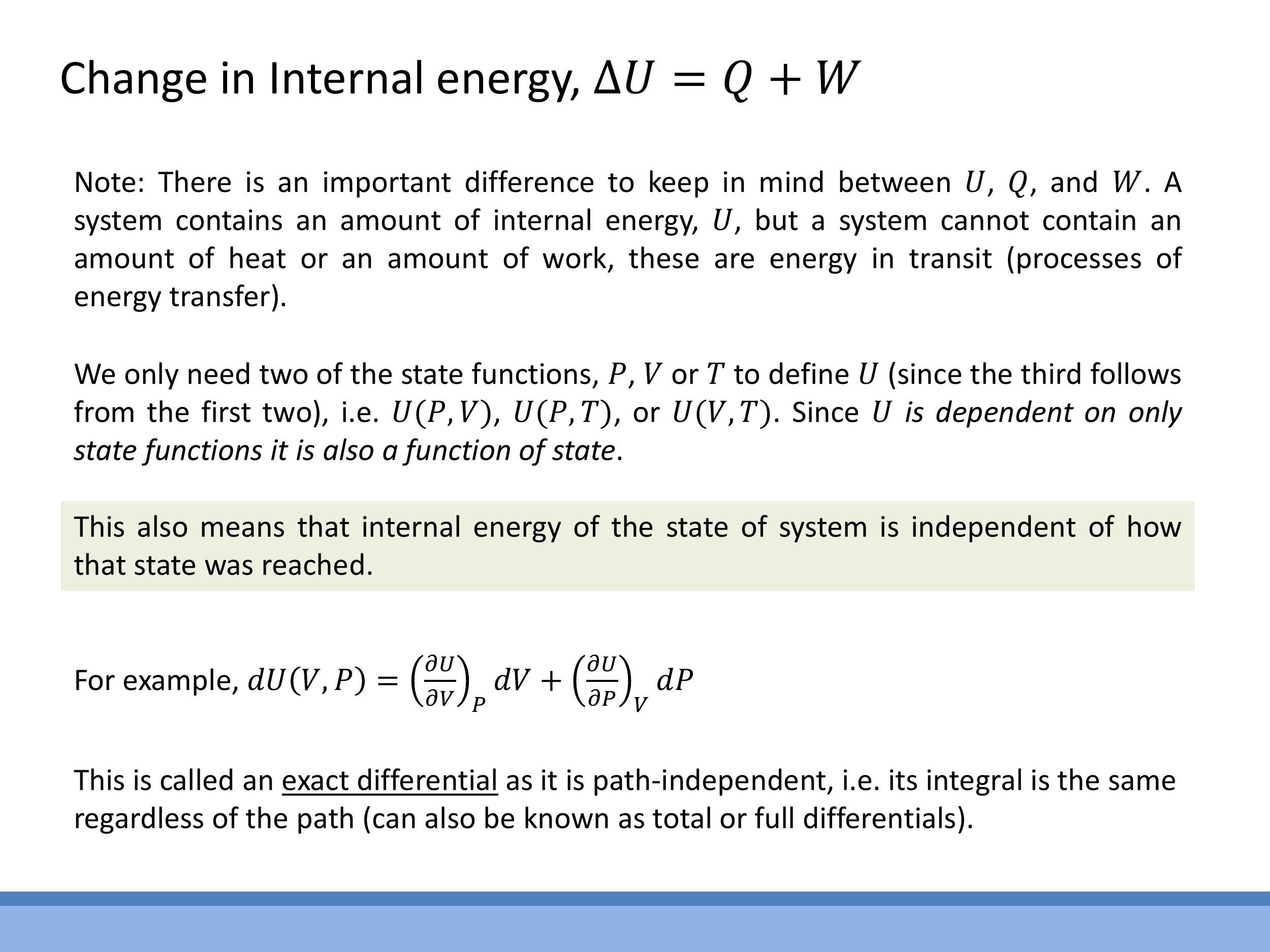

Internal energy ($U$) is defined as the sum of all microscopic energies within a system, including translational, rotational, and vibrational kinetic energies of its constituent particles, as well as potential energies arising from intermolecular forces in real gases. Crucially, $U$ is a state function: its value depends solely on the current macroscopic state of the system (e.g., defined by $P, V, T$) and is independent of the path or process taken to reach that state. In contrast, heat ($Q$) and work ($W$) are not state functions; they represent processes of energy transfer, often referred to as "energy in transit."

Because $U$ is a state function, only the change in internal energy ($\Delta U$) can be practically measured, rather than its absolute value. The exact differential $dU$ formalises this path independence; for example, $dU(V,P) = \left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial V}\right)_P dV + \left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial P}\right)_V dP$, meaning its integral between two states is unique regardless of the integration path.

The First Law of Thermodynamics is a statement of the conservation of energy. It describes how the internal energy of a system changes due to heat transfer and work done. A common form states that the change in internal energy ($\Delta U$) is the sum of the heat added to the system ($Q$) and the work done on the system ($W$):

$$

\Delta U = Q + W

$$

In this course, the differential form of the First Law, which defines the relationship between infinitesimal changes, will primarily be used as:

$$

dQ = dU + PdV

$$

In this convention, $PdV$ represents the work done by the system during an expansion. Physically, $dQ$ is the heat supplied to the system, $dU$ is the change in the system's internal energy, and $PdV$ is the work performed by the system against its surroundings. It is important to note that different texts may use different sign conventions for work; therefore, always verify the specific form being used.

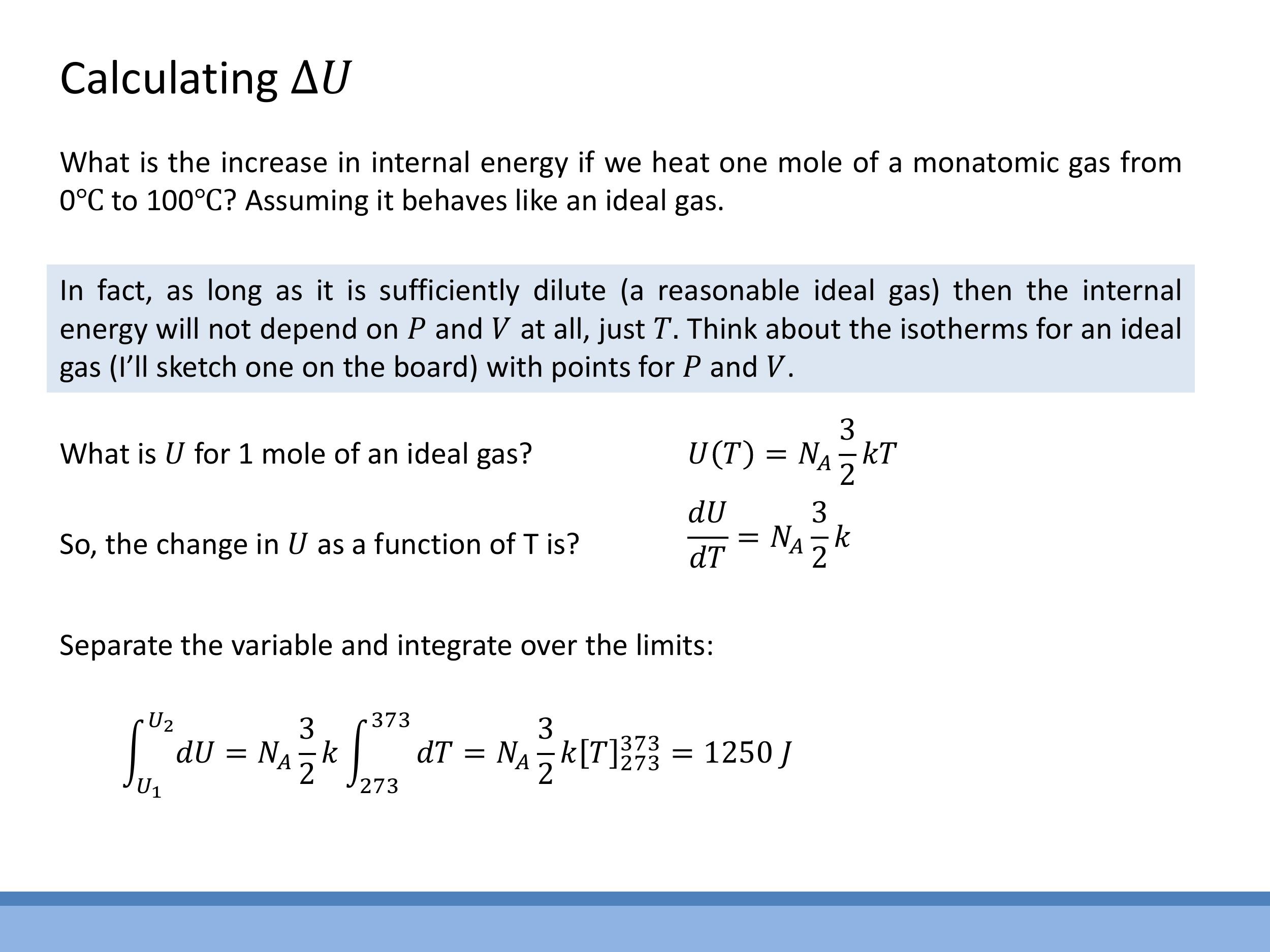

6) Worked example: $\Delta U$ for heating 1 mol monatomic ideal gas from 0°C to 100°C

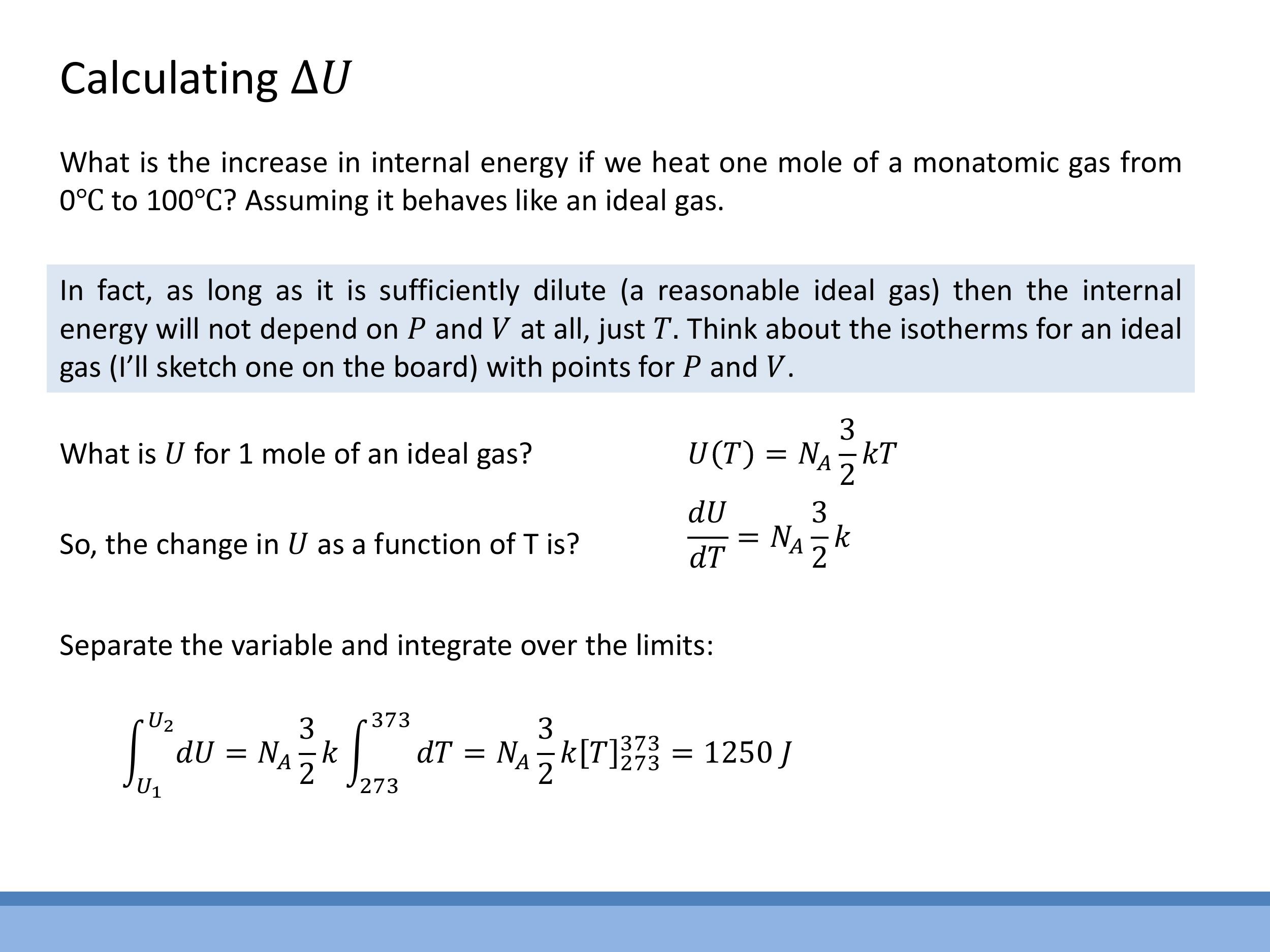

For one mole of a monatomic ideal gas, the internal energy $U$ consists solely of translational kinetic energy and is given by $U = \frac{3}{2}RT$. This implies that for an ideal gas, the internal energy depends only on temperature. To calculate the change in internal energy ($\Delta U$) when heating one mole of such a gas from $0^\circ\text{C}$ to $100^\circ\text{C}$:

First, find the differential change of $U$ with respect to $T$:

$$

\frac{dU}{dT} = \frac{3}{2}R

$$

To find $\Delta U$ over a temperature range, integrate this expression:

$$

\Delta U = \int_{U_1}^{U_2} dU = \int_{T_1}^{T_2} \frac{3}{2}R \, dT = \frac{3}{2}R [T]_{T_1}^{T_2} = \frac{3}{2}R (T_2 - T_1) = \frac{3}{2}R \Delta T

$$

Given $R \approx 8.314 \, \text{J mol}^{-1} \, \text{K}^{-1} $ and $ \Delta T = 100 \, \text{K} $ (from $ 0^\circ\text{C} $ to $ 100^\circ\text{C}$), the change in internal energy is:

$$

\Delta U = \frac{3}{2} \times 8.314\,\text{J mol}^{-1}\,\text{K}^{-1} \times 100\,\text{K} \approx 1250\,\text{J}

$$

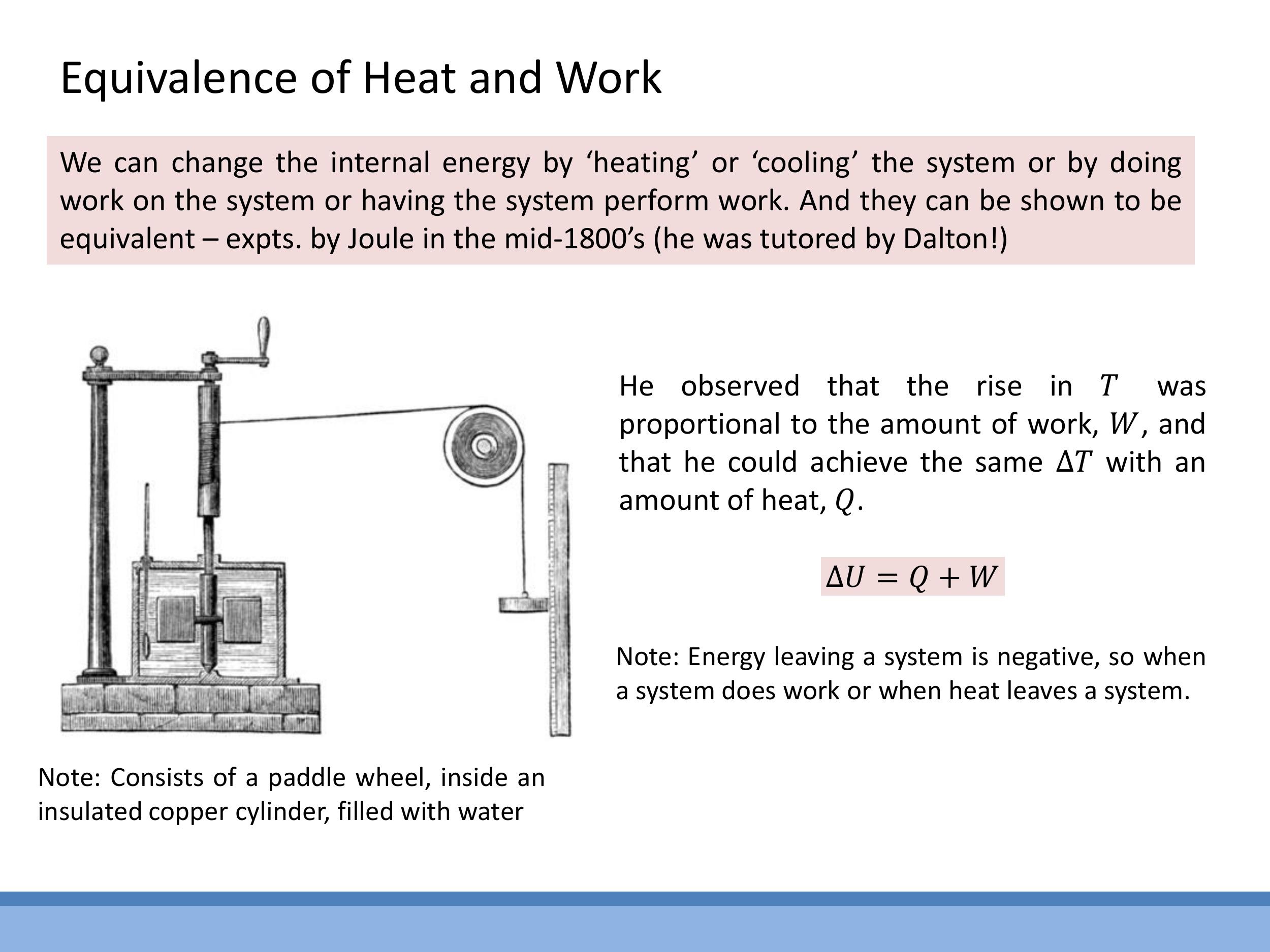

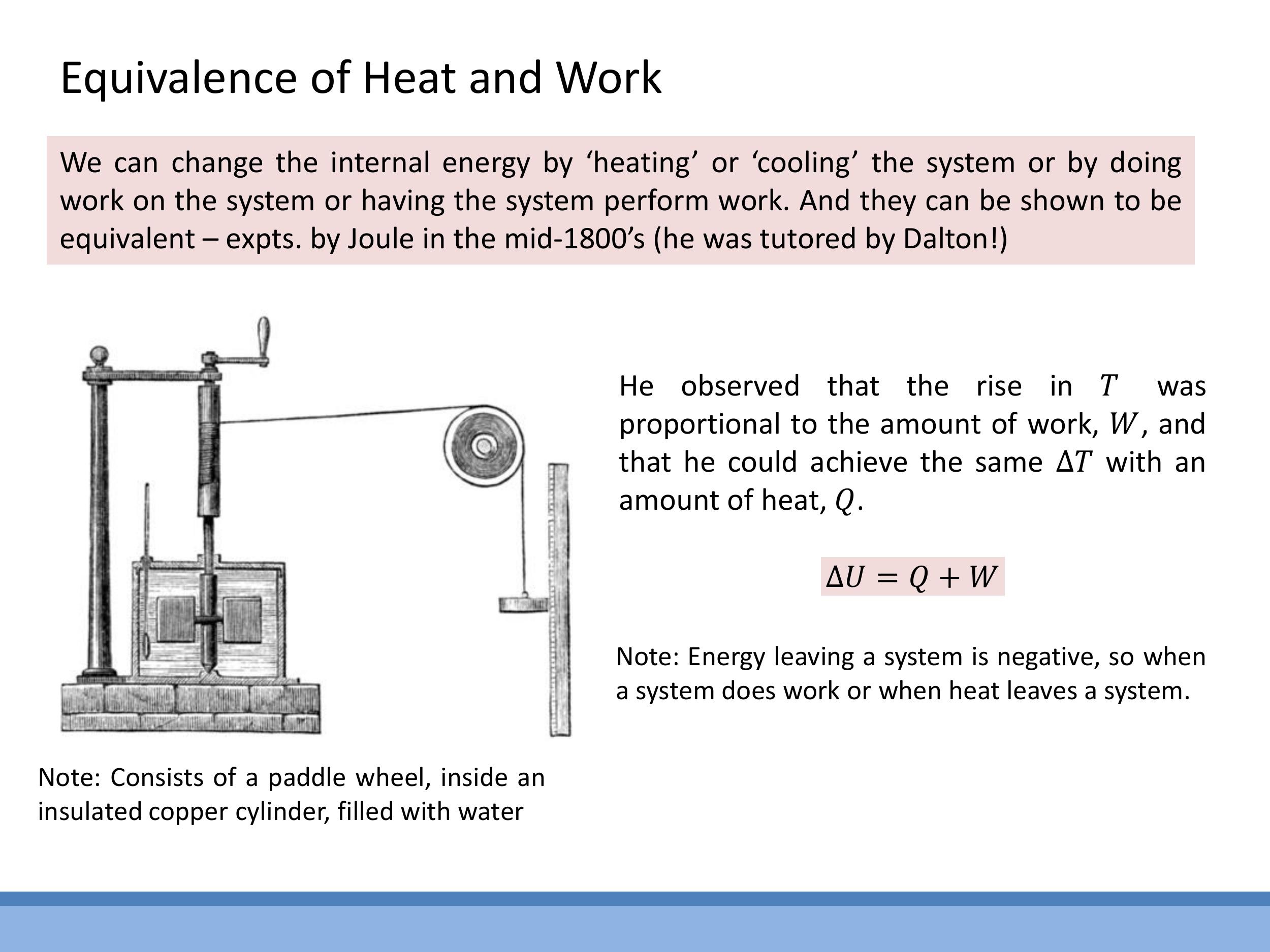

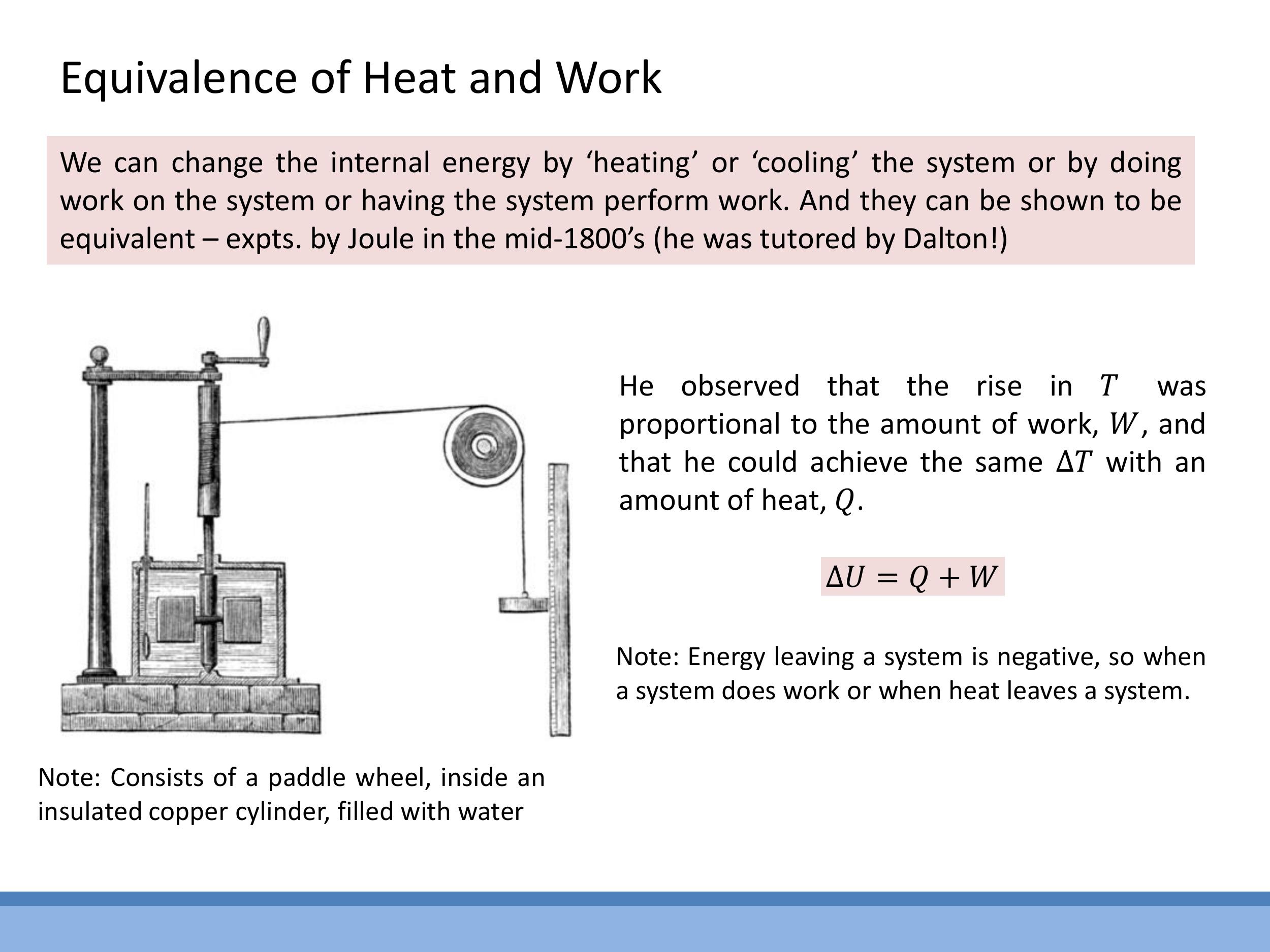

7) Joule’s experimental foundations: heat-work equivalence

James Prescott Joule conducted pioneering experiments that established the quantitative equivalence between heat and mechanical work, laying a crucial foundation for the First Law of Thermodynamics. In his famous paddle-wheel experiment, mechanical work was performed on a fluid (typically water) by falling weights driving a paddle wheel, resulting in a measurable temperature increase. Joule demonstrated that the same temperature rise could be achieved by supplying a specific amount of heat ($Q$) to the fluid, thus proving that work and heat are interconvertible forms of energy transfer that can both change a system's internal energy.

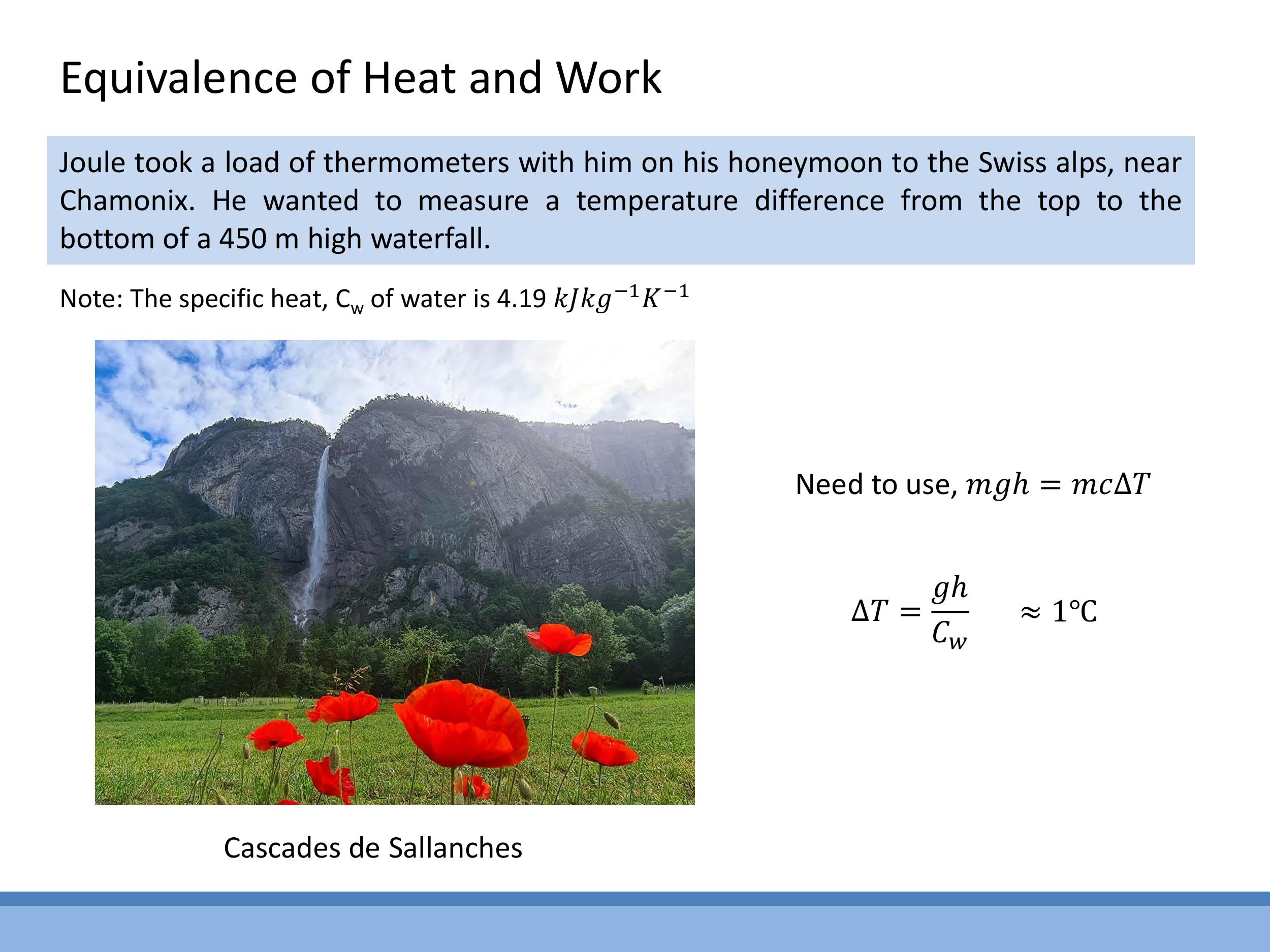

A vivid illustration of this principle comes from Joule's "waterfall estimate." During his honeymoon, Joule attempted to measure the temperature difference of water at the top and bottom of a waterfall in the Swiss Alps, approximately $450 \, \text{m} $ high. The gravitational potential energy lost by the falling water ($ mgh $) is converted into internal energy, manifesting as a temperature increase. By equating the potential energy to the thermal energy ($ mgh = mc_w\Delta T$), the expected temperature change can be estimated:

$$

\Delta T = \frac{gh}{c_w}

$$

Using $g \approx 9.8 \, \text{m s}^{-2} $, $ h = 450 \, \text{m} $, and the specific heat capacity of water $ c_w \approx 4190 \, \text{J kg}^{-1} \, \text{K}^{-1} $, the calculated temperature rise is approximately $ 1^\circ\text{C}$. This back-of-the-envelope calculation highlights the small but measurable effect of mechanical work on temperature.

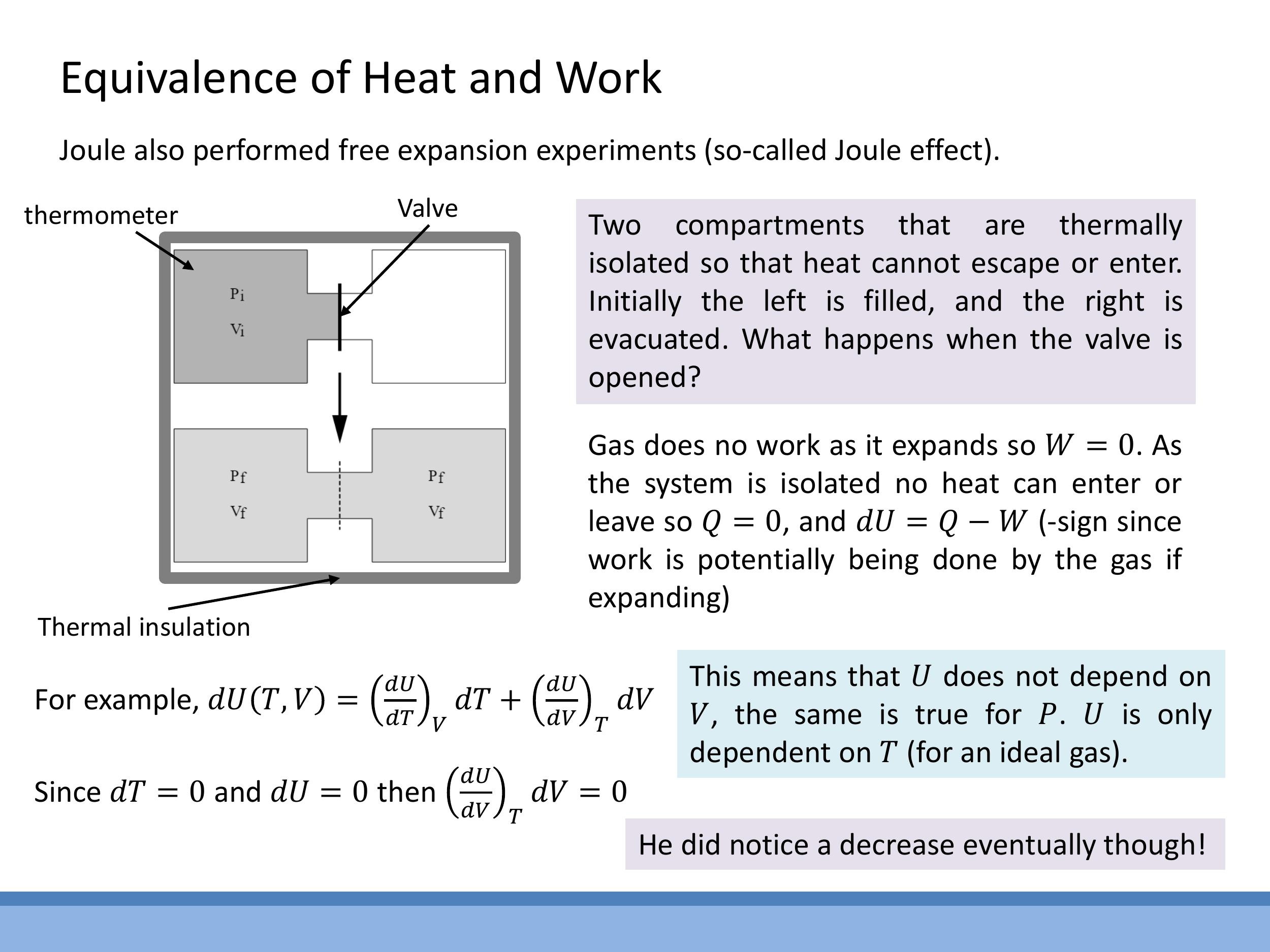

8) Joule free expansion: what $U$ depends on for an ideal gas

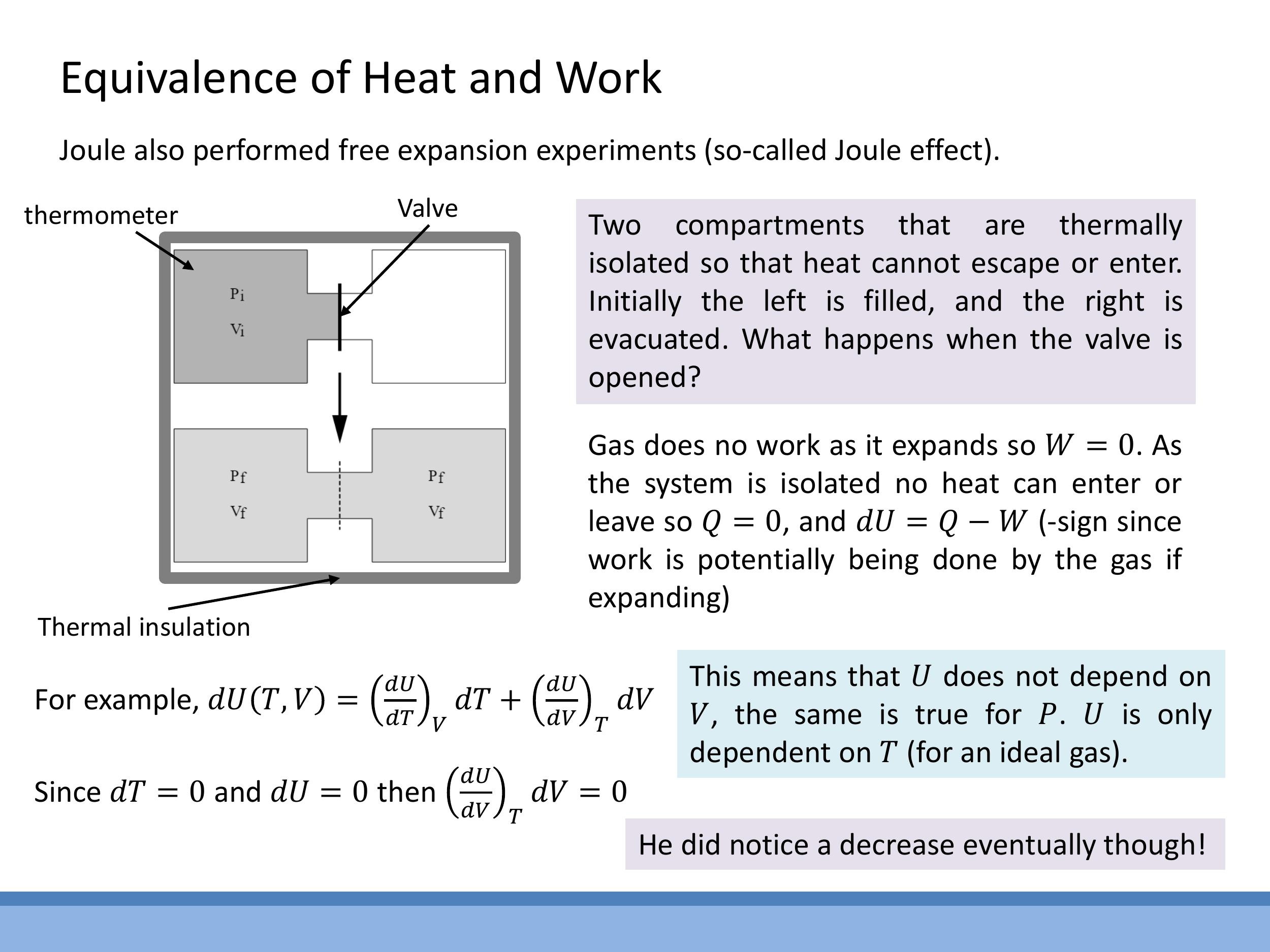

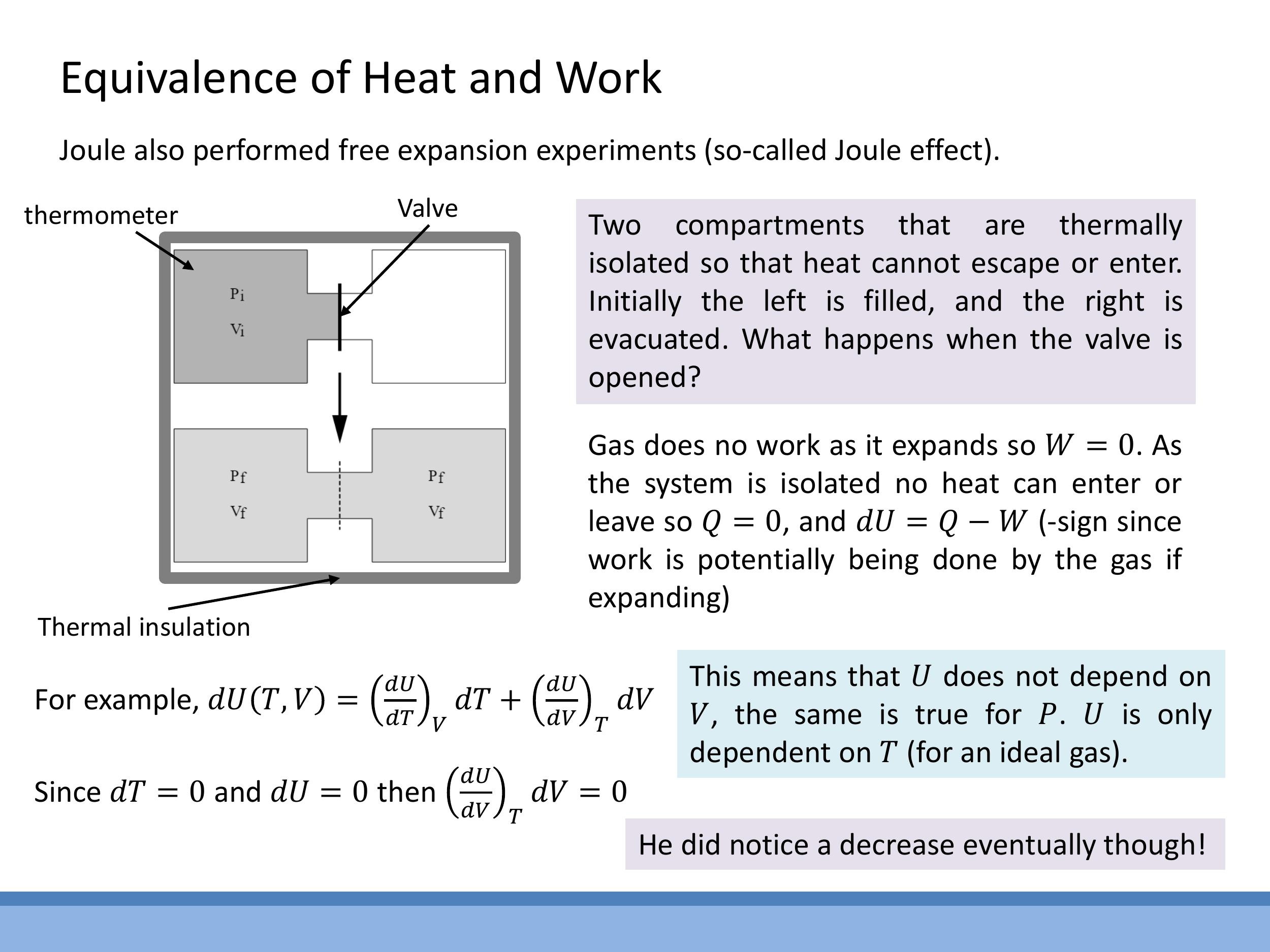

Joule's free expansion experiment was designed to investigate how the internal energy of a gas depends on its volume and pressure. The experimental setup consisted of a thermally insulated container divided into two compartments by a valve. One compartment held a gas, while the other was evacuated to a vacuum. When the valve was opened, the gas expanded freely to fill both compartments.

Under these conditions, no heat is exchanged with the surroundings (due to thermal insulation, $Q = 0$), and no external work is done by the gas as it expands into a vacuum ($W = 0$). According to the First Law of Thermodynamics, $\Delta U = Q + W$, which implies that for an ideal gas undergoing free expansion, $\Delta U = 0$. Experimentally, an ideal gas shows no temperature change ($\Delta T = 0$) during this process. Since pressure ($P$) and volume ($V$) clearly change while internal energy ($U$) and temperature ($T$) do not, this experiment demonstrates that for an ideal gas, internal energy is a function of temperature only

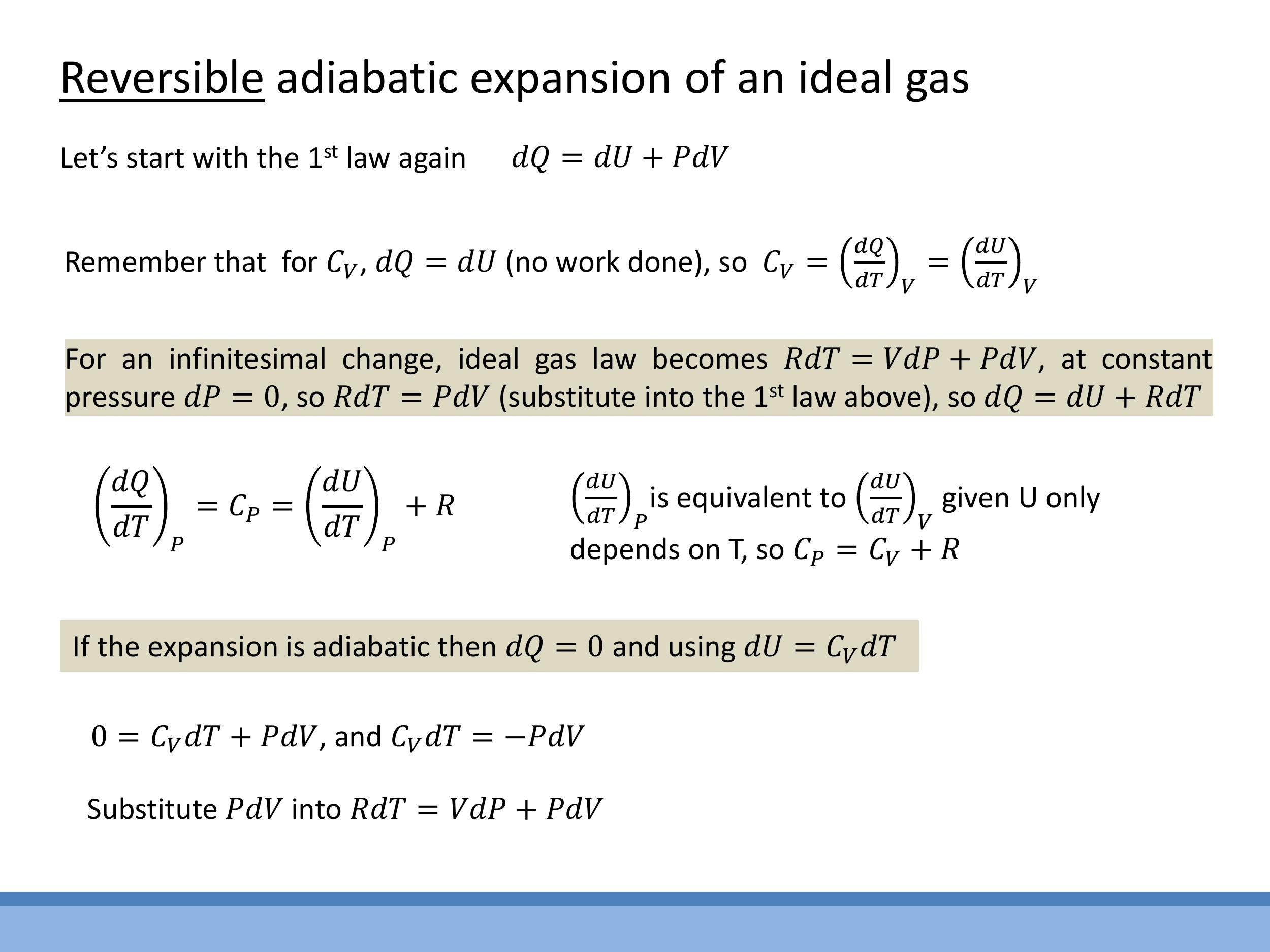

9) Setting up adiabatic process relations (derivation to be completed next lecture)

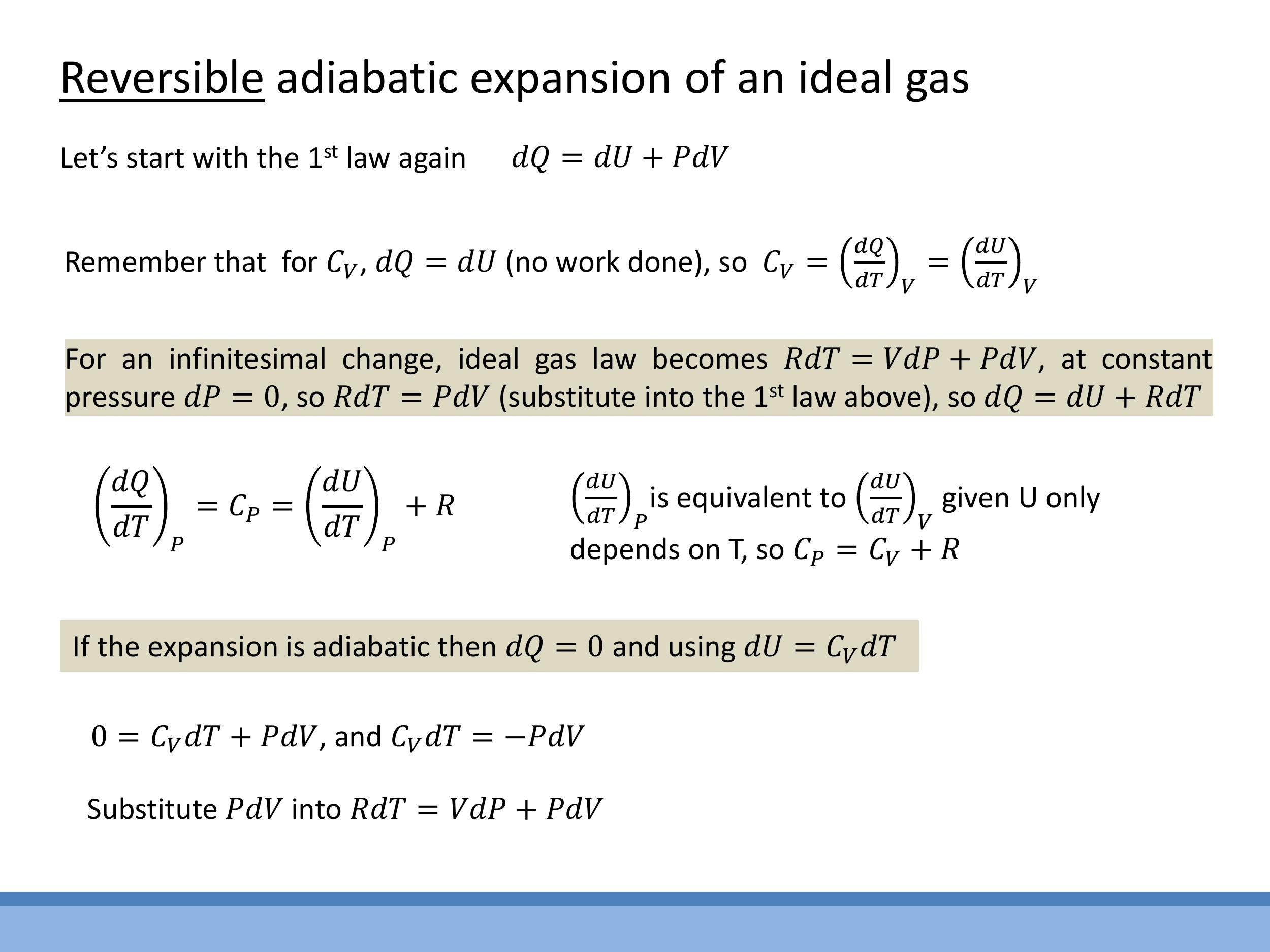

An adiabatic process is one in which no heat is exchanged with the surroundings, meaning $dQ = 0$. For an ideal gas, the change in internal energy is related to the change in temperature by $dU = C_V dT$, where $C_V$ is the molar heat capacity at constant volume. Starting from the First Law of Thermodynamics in the form $dQ = dU + PdV$, and applying the adiabatic condition, we get:

$$

0 = C_V dT + PdV

$$

This can be rearranged to $C_V dT = -PdV$. Furthermore, by combining the differential form of the ideal gas law ($RdT = VdP + PdV$) with the First Law at constant pressure, we can derive Mayer's relation, $C_P = C_V + R$, which links the molar heat capacities at constant pressure ($C_P$) and constant volume ($C_V$). These fundamental relationships form the basis for deriving the adiabatic process relations (e.g., $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$), which will be fully developed in the next lecture.

Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

The final result of the adiabatic derivation, specifically the $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$ relation and its integration steps, were presented on a slide but not covered in this lecture. The full derivation will be completed in the subsequent session.

Key takeaways

Real gases diverge from ideal gas behaviour due to intermolecular attractions and the finite size of molecules, leading to the formation of a two-phase "dome" and a critical point on $P$ - $V$ isotherms. The critical temperature $T_C$ is linked to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ by the approximate relation $kT_C \sim \varepsilon$. A system's macroscopic state is defined by state variables such as pressure ($P$), volume ($V$), and temperature ($T$). Internal energy ($U$) is also a state function, depending only on the system's current state, whereas heat ($Q$) and work ($W$) are processes of energy transfer.

The differential form of the ideal gas law for one mole, $RdT = VdP + PdV$, is a crucial identity connecting small changes in $T, P, V$. The First Law of Thermodynamics, in the course's preferred form $dQ = dU + PdV$ (where $PdV$ is work done by the system), states that heat added to a system either increases its internal energy or is used to perform expansion work. For an ideal monatomic gas, $U = \frac{3}{2}RT$, leading to $\Delta U = \frac{3}{2}R\Delta T$.

Joule's experiments established the equivalence of heat and work. For instance, a $450 \, \text{m} $ waterfall warms by approximately $ 1^\circ\text{C} $ due to the conversion of potential energy into internal energy ($ mgh = mc\Delta T $). The Joule free expansion experiment demonstrated that for an ideal gas, $ U $ depends solely on $ T $; with $ Q = 0 $ and $ W = 0 $, $ \Delta U = 0 $ results in $ \Delta T = 0 $, despite changes in $ P $ and $ V $. For adiabatic processes ($ dQ = 0 $) in an ideal gas, the First Law and $ dU = C_V dT $ lead to $ C_V dT = -PdV $. These relations, along with Mayer's relation ($ C_P = C_V + R $), are the foundation for the full derivation of adiabatic equations (like $ PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$), which will be completed in the next lecture.

## Lecture 9: First Law Revisited

This lecture provides a bridge from the discussion of real gases and phase diagrams to the operational application of the First Law of Thermodynamics. The primary goals are to clarify the distinction between state functions and processes, compute the change in internal energy ($\Delta U$) for an ideal gas, and establish the foundational relationships for adiabatic processes. By the end of this session, students will be able to calculate changes in internal energy from heat and work, understand heat capacities and their interdependence, grasp the implications of the Joule free expansion experiment, connect microscopic and macroscopic views of the First Law, and set up the initial conditions for an adiabatic expansion.

### 1) Recap: real-gas isotherms, the phase dome, and $T_C \sim \varepsilon/k$

Ideal gases obey the ideal gas law, $PV = RT$, which produces smooth hyperbolic isotherms on a pressure-volume ($P$-$V$) diagram. However, real gases exhibit deviations at lower temperatures, where intermolecular forces become significant. This leads to the appearance of a "two-phase region" or "dome" in $P$-$V$ isotherms, representing gas-liquid coexistence, which is resolved physically by the process of condensation. These deviations arise because real gas molecules have finite size, reducing the available volume (addressed by the van der Waals $nb$ term), and experience intermolecular attractions, which reduce the measured wall pressure (addressed by the van der Waals $a/V^2$ term).

The critical isotherm, at a specific critical temperature ($T_C$), marks the boundary above which a gas cannot be liquefied by compression alone; the liquid and gas phases become indistinguishable, forming a supercritical fluid. This critical temperature provides a link between macroscopic behaviour and microscopic energy scales, as the thermal energy $kT_C$ is approximately equal to the intermolecular binding energy $\varepsilon$, leading to the relation $T_C \sim \frac{\varepsilon}{k}$. This allows for estimation of the critical temperature if the bond energy is known. Water exhibits an anomalous phase diagram where the solid-liquid boundary has a negative slope, meaning that increasing pressure can melt ice. This is due to ice being less dense than liquid water, a rare but crucial property.

### 2) Thermodynamic terms and state functions

In thermodynamics, a common model system consists of a gas confined within a cylinder by a frictionless piston. The walls of the cylinder can be classified as either diathermal, allowing heat to flow through, or adiabatic, preventing any heat transfer. A system is in thermodynamic equilibrium when its macroscopic properties remain constant, encompassing mechanical equilibrium (no net forces), thermal equilibrium (no net heat flow), and chemical equilibrium (no net change in chemical composition).

The macroscopic state of a system is defined by state variables such as pressure ($P$), volume ($V$), and temperature ($T$). These are known as state functions because their values depend only on the current state of the system, not on the path taken to reach that state. Any mathematical relationship between these state variables, such as the ideal gas law ($PV = RT$ for one mole), is termed an equation of state.

### 3) Differential form of the ideal gas law

To analyse small changes in a thermodynamic system, the ideal gas law can be expressed in a differential form. Starting with the ideal gas law for one mole, $PV = RT$, and applying the product rule to the left-hand side for an infinitesimal change, $d(PV) = PdV + VdP$. Since $R$ is a constant, the change on the right-hand side is $d(RT) = RdT$. Equating these expressions yields the differential form of the ideal gas law for one mole:

$$ RdT = VdP + PdV $$

This identity links small changes in temperature ($dT$) to corresponding small changes in pressure ($dP$) and volume ($dV$), serving as a fundamental tool for calculations involving thermodynamic processes. Generalisation to $n$ moles is straightforward by replacing $R$ with $nR$.

### 4) Internal energy $U$: what it is and what we can measure

Internal energy ($U$) is defined as the sum of all microscopic energies within a system, including translational, rotational, and vibrational kinetic energies of its constituent particles, as well as potential energies arising from intermolecular forces in real gases. Crucially, $U$ is a state function: its value depends solely on the current macroscopic state of the system (e.g., defined by $P, V, T$) and is independent of the path or process taken to reach that state. In contrast, heat ($Q$) and work ($W$) are not state functions; they represent processes of energy transfer, often referred to as "energy in transit."

Because $U$ is a state function, only the change in internal energy ($\Delta U$) can be practically measured, rather than its absolute value. The exact differential $dU$ formalises this path independence; for example, $dU(V,P) = \left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial V}\right)_P dV + \left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial P}\right)_V dP$, meaning its integral between two states is unique regardless of the integration path.

### 5) The First Law: forms and sign convention used in this course

The First Law of Thermodynamics is a statement of the conservation of energy. It describes how the internal energy of a system changes due to heat transfer and work done. A common form states that the change in internal energy ($\Delta U$) is the sum of the heat added to the system ($Q$) and the work done on the system ($W$):

$$ \Delta U = Q + W $$

In this course, the differential form of the First Law, which defines the relationship between infinitesimal changes, will primarily be used as:

$$ dQ = dU + PdV $$

In this convention, $PdV$ represents the work done *by* the system during an expansion. Physically, $dQ$ is the heat supplied to the system, $dU$ is the change in the system's internal energy, and $PdV$ is the work performed by the system against its surroundings. It is important to note that different texts may use different sign conventions for work; therefore, always verify the specific form being used.

### 6) Worked example: $\Delta U$ for heating 1 mol monatomic ideal gas from 0°C to 100°C

For one mole of a monatomic ideal gas, the internal energy $U$ consists solely of translational kinetic energy and is given by $U = \frac{3}{2}RT$. This implies that for an ideal gas, the internal energy depends only on temperature. To calculate the change in internal energy ($\Delta U$) when heating one mole of such a gas from $0^\circ\text{C}$ to $100^\circ\text{C}$:

First, find the differential change of $U$ with respect to $T$:

$$ \frac{dU}{dT} = \frac{3}{2}R $$

To find $\Delta U$ over a temperature range, integrate this expression:

$$ \Delta U = \int_{U_1}^{U_2} dU = \int_{T_1}^{T_2} \frac{3}{2}R \, dT = \frac{3}{2}R [T]_{T_1}^{T_2} = \frac{3}{2}R (T_2 - T_1) = \frac{3}{2}R \Delta T $$

Given $R \approx 8.314\,\text{J mol}^{-1}\,\text{K}^{-1}$ and $\Delta T = 100\,\text{K}$ (from $0^\circ\text{C}$ to $100^\circ\text{C}$), the change in internal energy is:

$$ \Delta U = \frac{3}{2} \times 8.314\,\text{J mol}^{-1}\,\text{K}^{-1} \times 100\,\text{K} \approx 1250\,\text{J} $$

### 7) Joule’s experimental foundations: heat-work equivalence

James Prescott Joule conducted pioneering experiments that established the quantitative equivalence between heat and mechanical work, laying a crucial foundation for the First Law of Thermodynamics. In his famous paddle-wheel experiment, mechanical work was performed on a fluid (typically water) by falling weights driving a paddle wheel, resulting in a measurable temperature increase. Joule demonstrated that the same temperature rise could be achieved by supplying a specific amount of heat ($Q$) to the fluid, thus proving that work and heat are interconvertible forms of energy transfer that can both change a system's internal energy.

A vivid illustration of this principle comes from Joule's "waterfall estimate." During his honeymoon, Joule attempted to measure the temperature difference of water at the top and bottom of a waterfall in the Swiss Alps, approximately $450\,\text{m}$ high. The gravitational potential energy lost by the falling water ($mgh$) is converted into internal energy, manifesting as a temperature increase. By equating the potential energy to the thermal energy ($mgh = mc_w\Delta T$), the expected temperature change can be estimated:

$$ \Delta T = \frac{gh}{c_w} $$

Using $g \approx 9.8\,\text{m s}^{-2}$, $h = 450\,\text{m}$, and the specific heat capacity of water $c_w \approx 4190\,\text{J kg}^{-1}\,\text{K}^{-1}$, the calculated temperature rise is approximately $1^\circ\text{C}$. This back-of-the-envelope calculation highlights the small but measurable effect of mechanical work on temperature.

### 8) Joule free expansion: what $U$ depends on for an ideal gas

Joule's free expansion experiment was designed to investigate how the internal energy of a gas depends on its volume and pressure. The experimental setup consisted of a thermally insulated container divided into two compartments by a valve. One compartment held a gas, while the other was evacuated to a vacuum. When the valve was opened, the gas expanded freely to fill both compartments.

Under these conditions, no heat is exchanged with the surroundings (due to thermal insulation, $Q = 0$), and no external work is done by the gas as it expands into a vacuum ($W = 0$). According to the First Law of Thermodynamics, $\Delta U = Q + W$, which implies that for an ideal gas undergoing free expansion, $\Delta U = 0$. Experimentally, an ideal gas shows no temperature change ($\Delta T = 0$) during this process. Since pressure ($P$) and volume ($V$) clearly change while internal energy ($U$) and temperature ($T$) do not, this experiment demonstrates that for an **ideal gas, internal energy is a function of temperature only**. For real gases, a small cooling effect is observed because the gas performs internal work against its attractive intermolecular forces during expansion, converting some kinetic energy into potential energy.

### 9) Setting up adiabatic process relations (derivation to be completed next lecture)

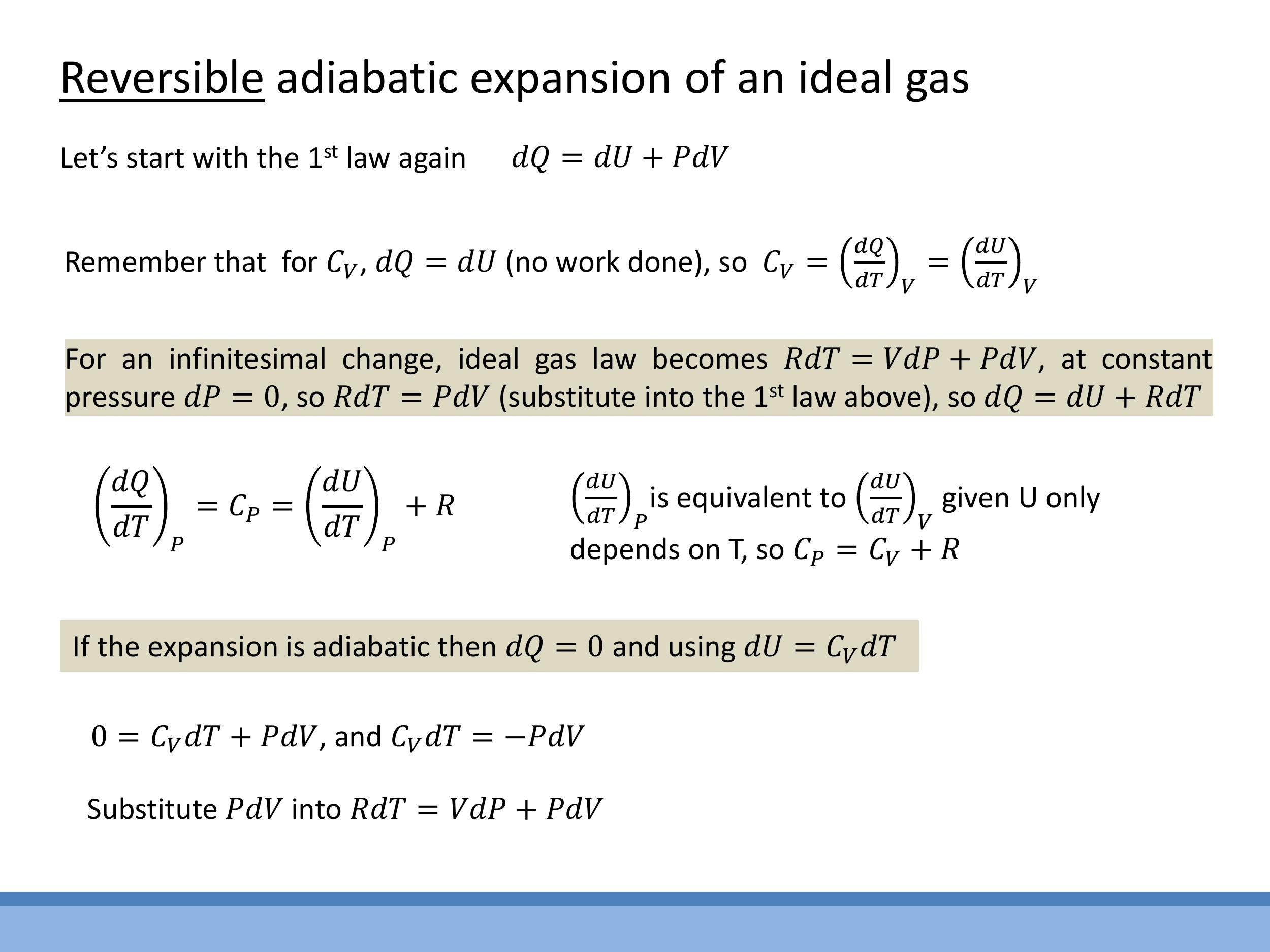

An adiabatic process is one in which no heat is exchanged with the surroundings, meaning $dQ = 0$. For an ideal gas, the change in internal energy is related to the change in temperature by $dU = C_V dT$, where $C_V$ is the molar heat capacity at constant volume. Starting from the First Law of Thermodynamics in the form $dQ = dU + PdV$, and applying the adiabatic condition, we get:

$$ 0 = C_V dT + PdV $$

This can be rearranged to $C_V dT = -PdV$. Furthermore, by combining the differential form of the ideal gas law ($RdT = VdP + PdV$) with the First Law at constant pressure, we can derive Mayer's relation, $C_P = C_V + R$, which links the molar heat capacities at constant pressure ($C_P$) and constant volume ($C_V$). These fundamental relationships form the basis for deriving the adiabatic process relations (e.g., $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$), which will be fully developed in the next lecture.

### Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

The final result of the adiabatic derivation, specifically the $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$ relation and its integration steps, were presented on a slide but not covered in this lecture. The full derivation will be completed in the subsequent session.

## Key takeaways

Real gases diverge from ideal gas behaviour due to intermolecular attractions and the finite size of molecules, leading to the formation of a two-phase "dome" and a critical point on $P$-$V$ isotherms. The critical temperature $T_C$ is linked to the microscopic separation energy $\varepsilon$ by the approximate relation $kT_C \sim \varepsilon$. A system's macroscopic state is defined by state variables such as pressure ($P$), volume ($V$), and temperature ($T$). Internal energy ($U$) is also a state function, depending only on the system's current state, whereas heat ($Q$) and work ($W$) are processes of energy transfer.

The differential form of the ideal gas law for one mole, $RdT = VdP + PdV$, is a crucial identity connecting small changes in $T, P, V$. The First Law of Thermodynamics, in the course's preferred form $dQ = dU + PdV$ (where $PdV$ is work done by the system), states that heat added to a system either increases its internal energy or is used to perform expansion work. For an ideal monatomic gas, $U = \frac{3}{2}RT$, leading to $\Delta U = \frac{3}{2}R\Delta T$.

Joule's experiments established the equivalence of heat and work. For instance, a $450\,\text{m}$ waterfall warms by approximately $1^\circ\text{C}$ due to the conversion of potential energy into internal energy ($mgh = mc\Delta T$). The Joule free expansion experiment demonstrated that for an ideal gas, $U$ depends solely on $T$; with $Q = 0$ and $W = 0$, $\Delta U = 0$ results in $\Delta T = 0$, despite changes in $P$ and $V$. For adiabatic processes ($dQ = 0$) in an ideal gas, the First Law and $dU = C_V dT$ lead to $C_V dT = -PdV$. These relations, along with Mayer's relation ($C_P = C_V + R$), are the foundation for the full derivation of adiabatic equations (like $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$), which will be completed in the next lecture.