Lecture 10: Reversible Processes and Adiabatic Expansion (Diesel Engine)

0) Orientation, admin, and quick review

This lecture builds on previous discussions of the First Law of Thermodynamics, alongside concepts of work, heat, and ideal gas differentials. Today, we'll delve into distinguishing between reversible and irreversible processes and calculating work for isothermal and adiabatic changes. We'll derive and apply the adiabatic relations, $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$ and $TV^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}$, and see how adiabatic compression applies to the diesel engine. Finally, we'll introduce enthalpy, $H = U + PV$, a concept that will be crucial for understanding later thermodynamic cycles and the Second Law.

Before we begin, a student research project is inviting participation to gather feedback on first-year physics learning. This is an optional, extra-curricular opportunity, and details for signing up will be available after the lecture.

As a quick recap, remember that internal energy $U$ is a state function, meaning its value depends only on the system's current state, not on the path taken to reach it. In contrast, heat $Q$ and work $W$ are processes of energy transfer. Throughout this course, we primarily use the differential form of the First Law: $dQ = dU + PdV$, where $PdV$ represents the work done by the system. This convention helps us in deriving relationships for various thermodynamic processes.

1) What thermodynamic reversibility really means

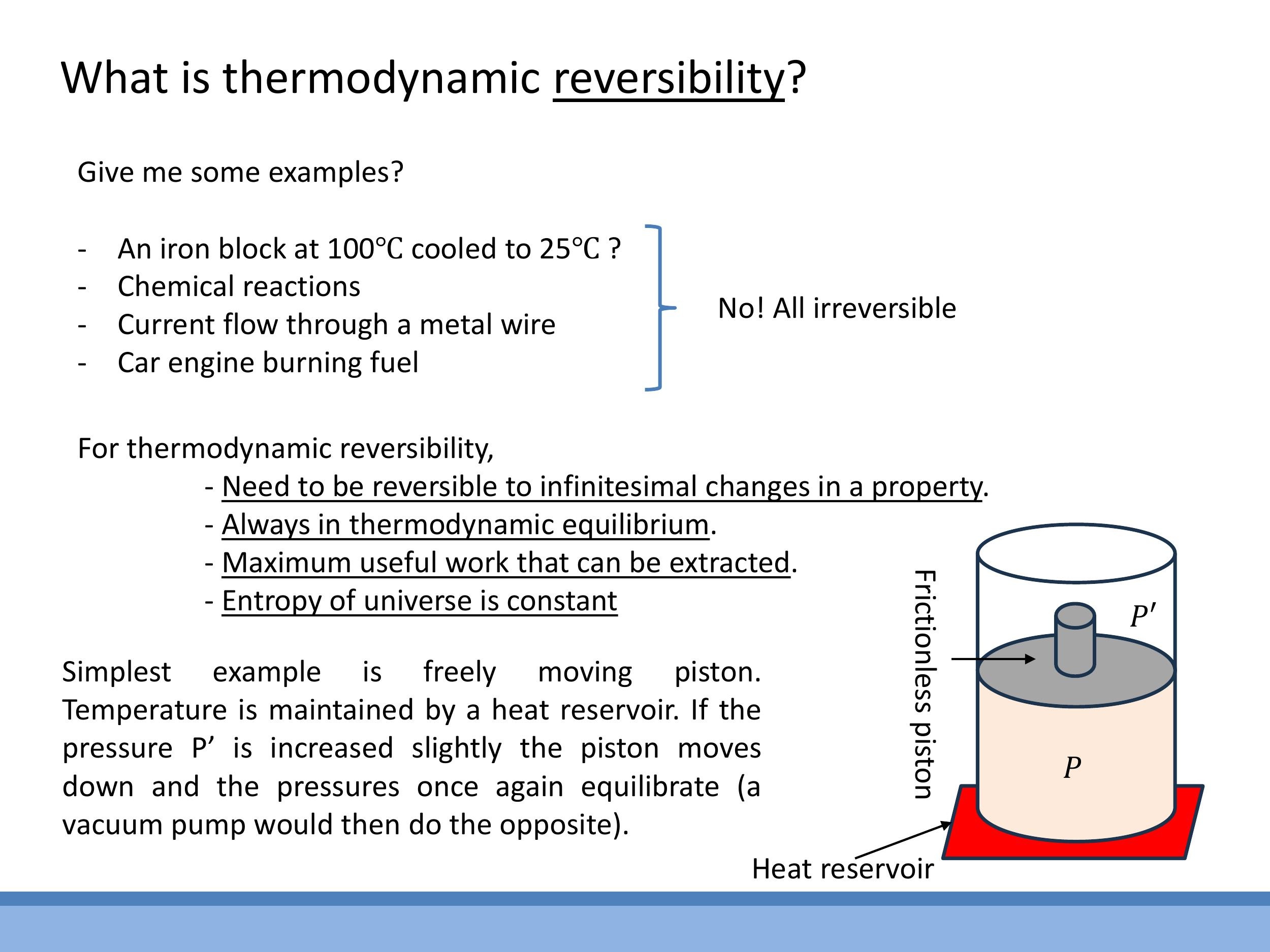

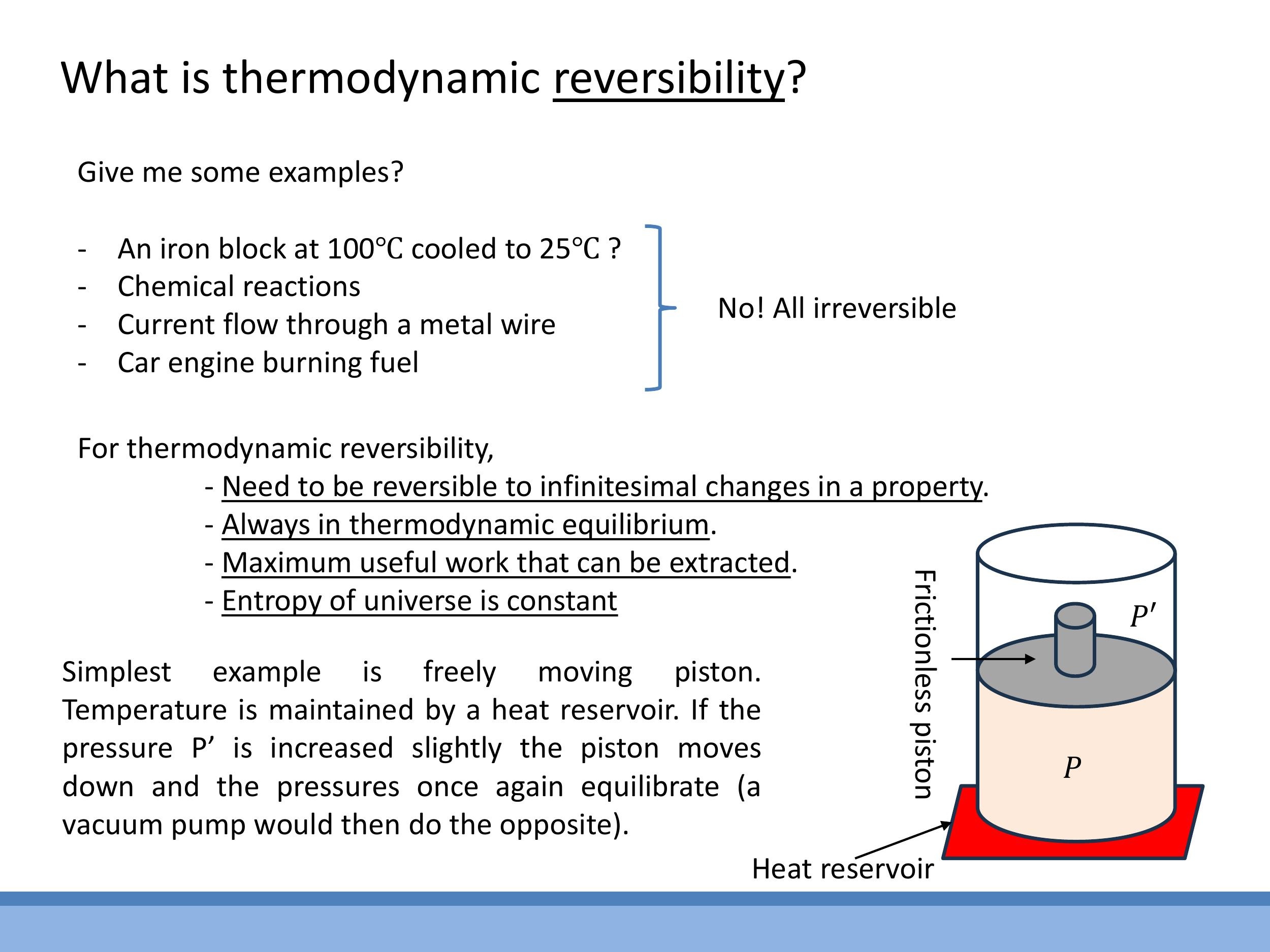

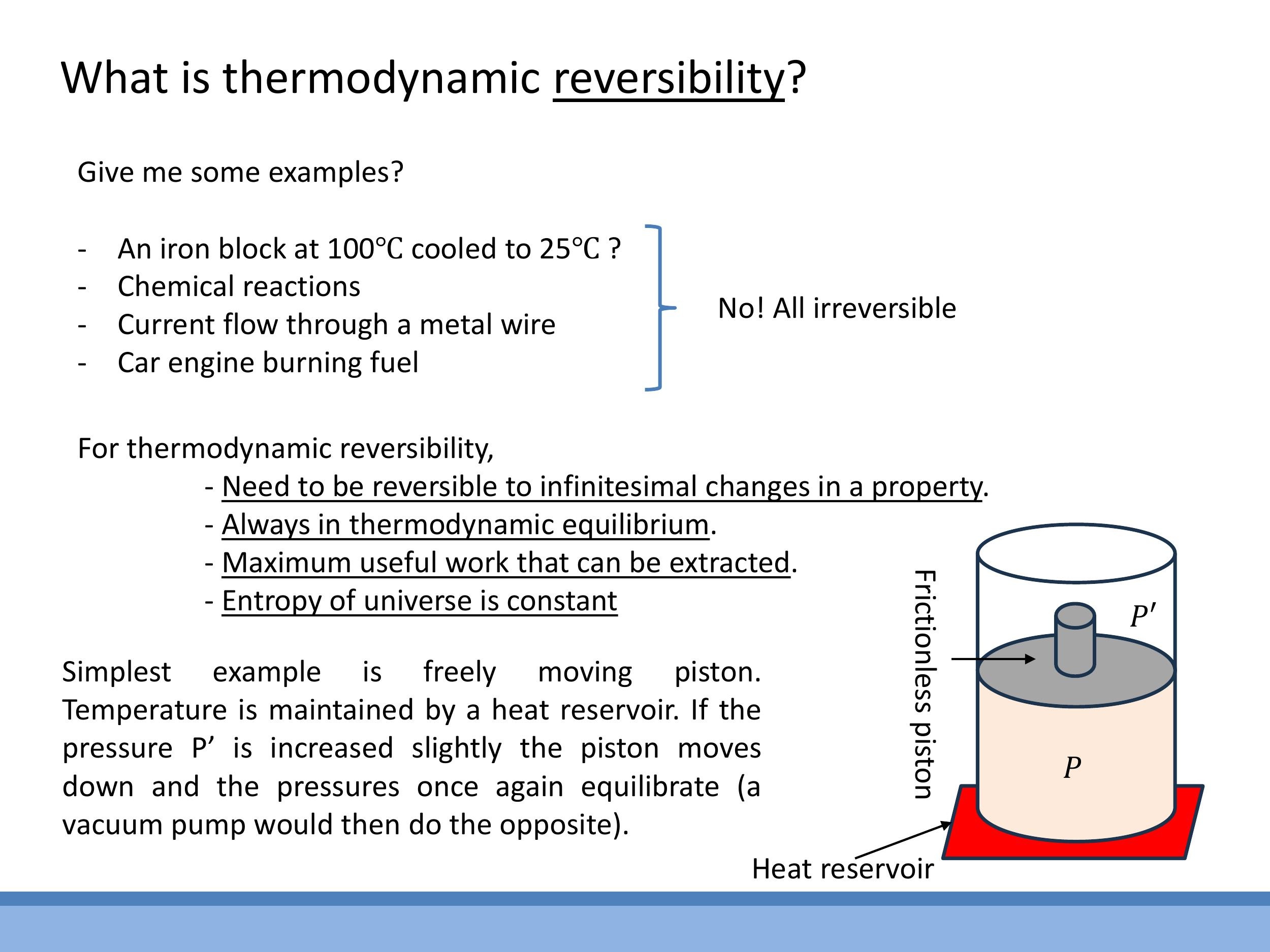

To understand thermodynamic efficiency, it's crucial to grasp the concept of reversibility. Many everyday processes are, in fact, thermodynamically irreversible. Consider a hot iron block cooling in room air, a chemical reaction, a steady current flowing through a wire, or fuel burning in an engine. In all these cases, a minuscule change in the surroundings won't reverse the process. For instance, if a $100 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ block is cooling, a tiny $ 0.1 \, ^\circ\text{C}$ increase in the ambient air temperature won't cause the block to start heating up again.

An ideal reversible process operates under very specific, idealised conditions. The system must remain in thermodynamic equilibrium throughout the entire process, meaning its macroscopic properties are unchanging. Such a process is reversible to infinitesimal changes in any property; a tiny alteration in the surroundings can flip the direction of the change. A reversible process is also one that extracts the maximum possible useful work from a system. Importantly, for a reversible process, the total entropy of the universe (the system plus its surroundings) remains unchanged. While a full treatment of entropy will come later, it's useful to think of it here as a measure of disorder.

The frictionless piston model provides a good physical anchor for understanding reversibility. Imagine a piston moving freely within a cylinder, in equilibrium with a heat reservoir. If the temperature of the heat reservoir is increased infinitesimally, the piston will move slightly upwards. Conversely, a tiny decrease in the reservoir's temperature will cause the piston to move slightly downwards. This sensitivity to infinitesimal changes in either direction is a hallmark of a reversible process.

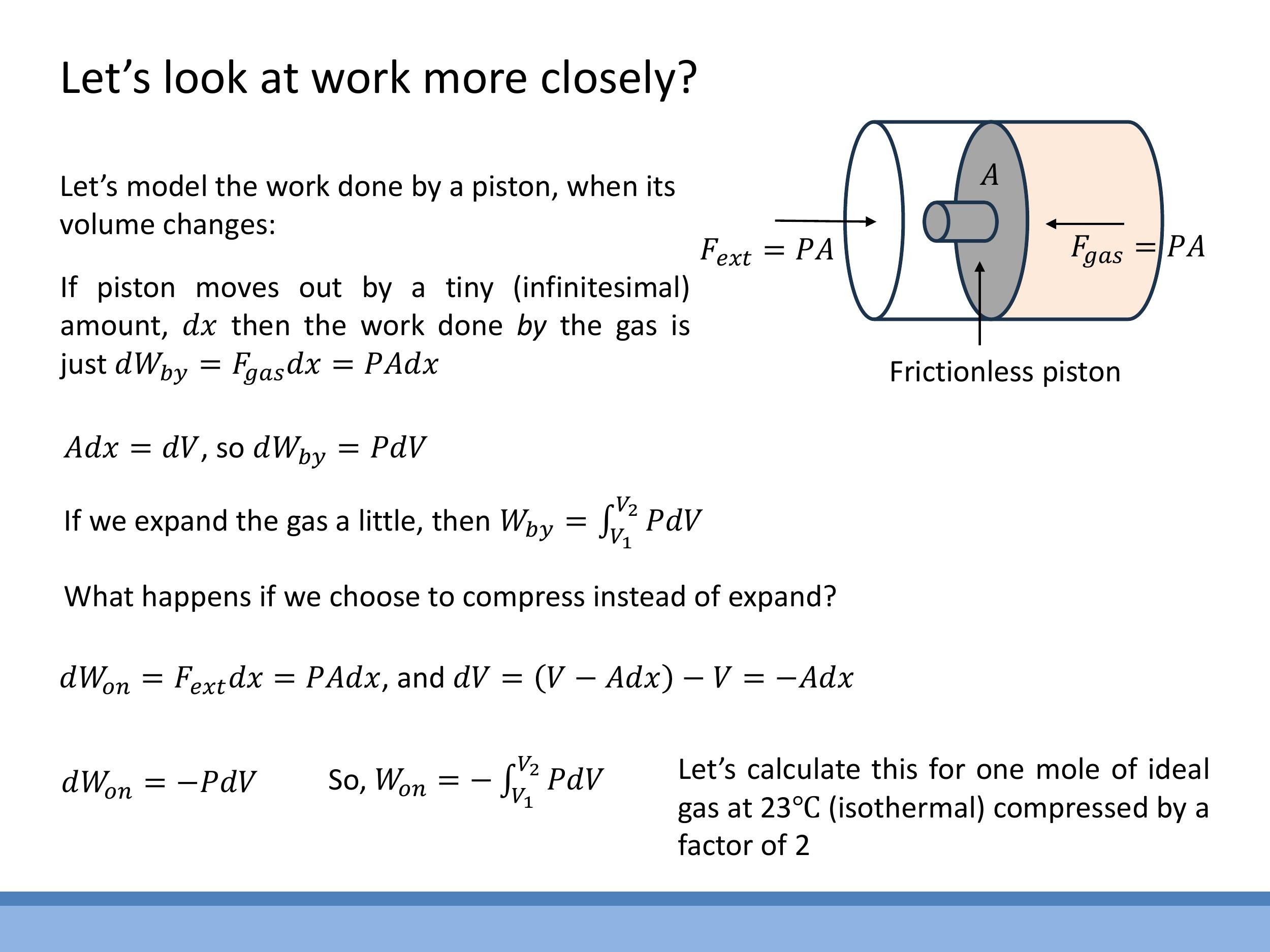

2) Work in P-V processes: from forces to dW = PdV

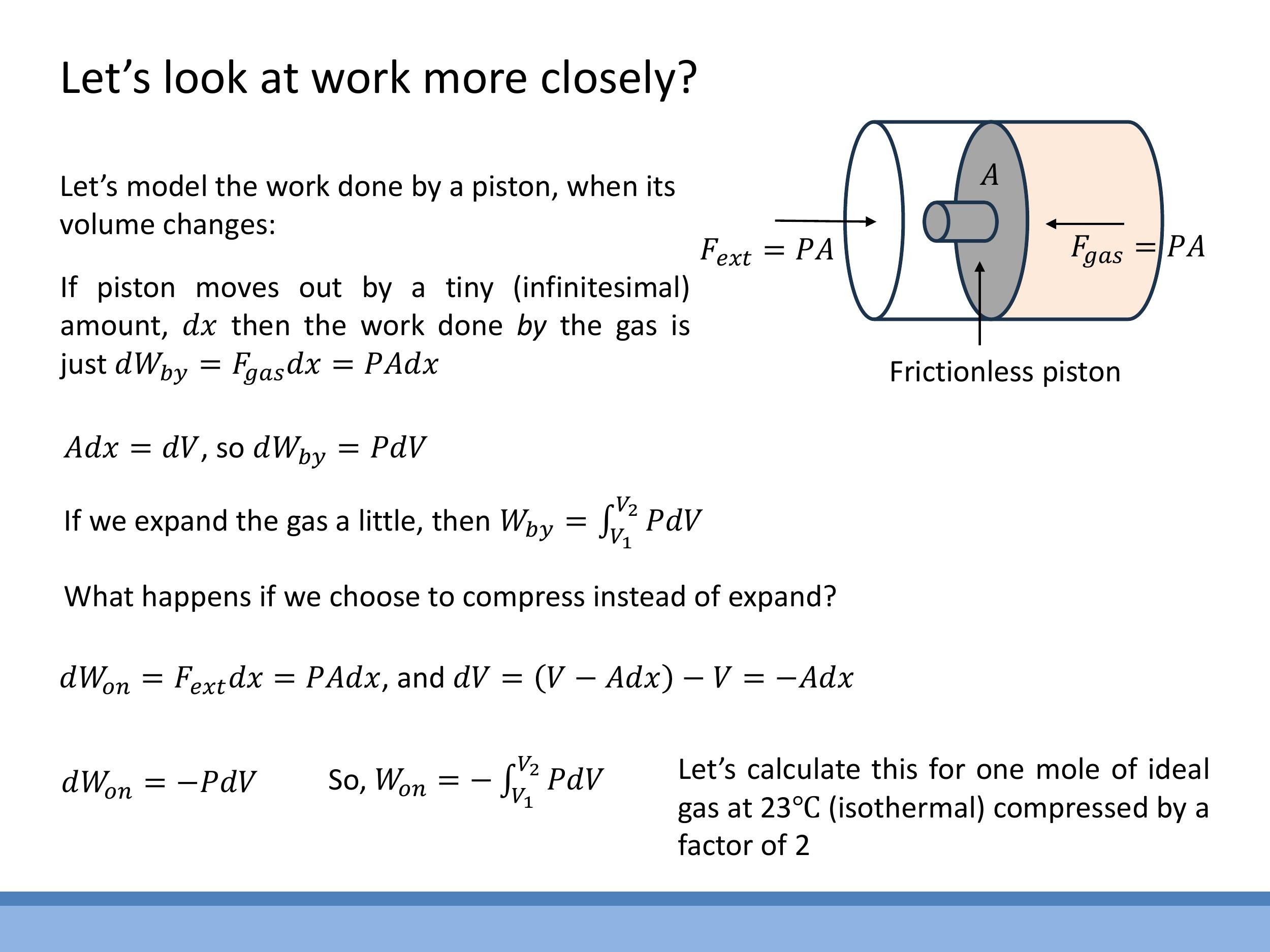

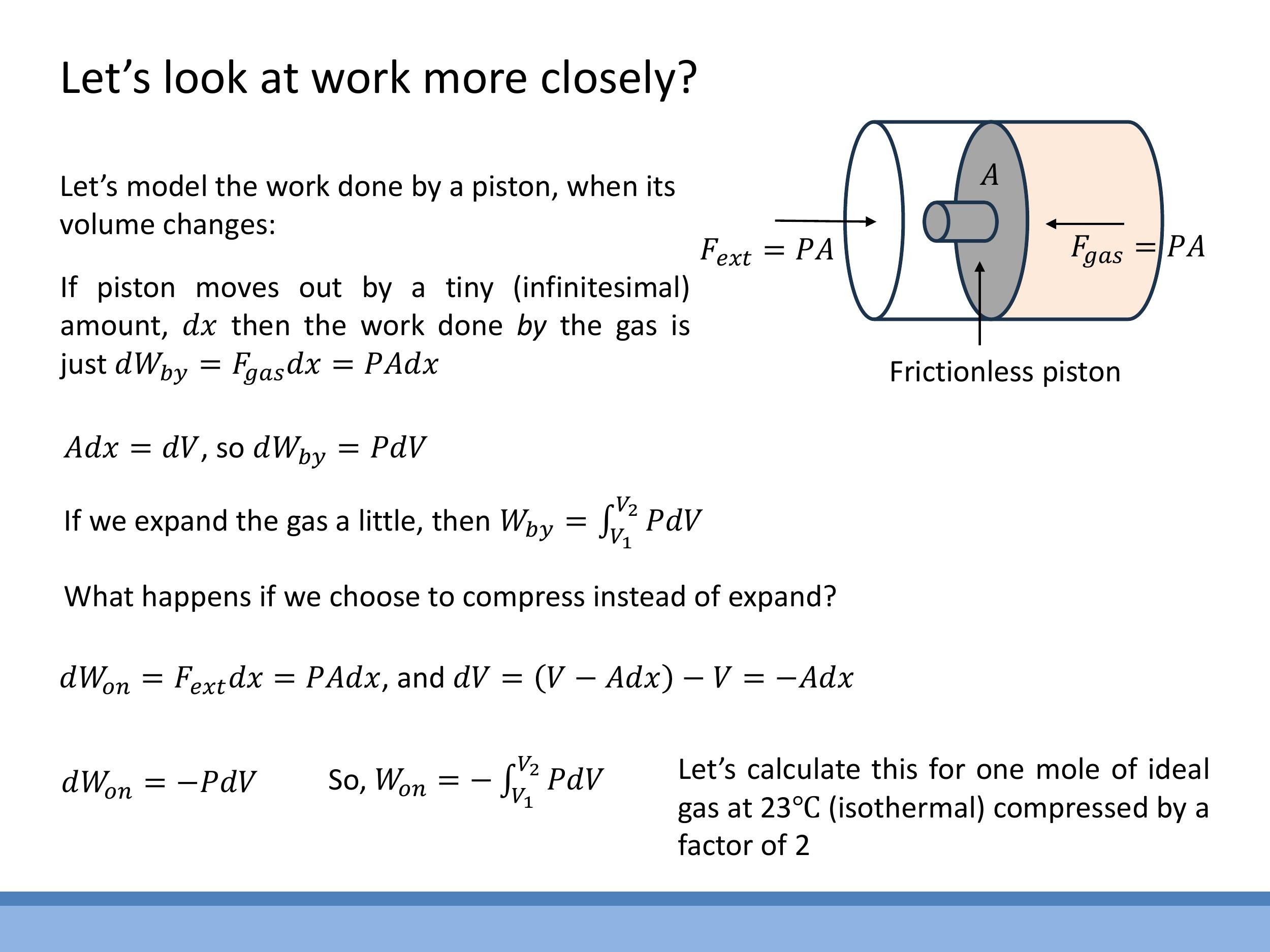

To understand energy transformations in gases, we need to precisely define the work done during changes in volume. When a gas expands, it does work by the system. Consider a piston moving outwards by an infinitesimal distance $dx$. The force exerted by the gas is $F_\text{gas} = PA$, where $P$ is the pressure and $A$ is the piston's cross-sectional area. The infinitesimal work done by the gas, $dW_\text{by}$, is $F_\text{gas} dx = P A dx$. Since $A dx$ is the infinitesimal change in volume, $dV$, we can write:

$$

dW_\text{by} = P dV

$$

Conversely, if we compress the gas, work is done on the system. In this case, the piston moves inwards, so the change in volume $dV$ is negative. The work done on the gas, $dW_\text{on}$, is given by:

$$

dW_\text{on} = -P dV

$$

The total work done along a path from an initial volume $V_1$ to a final volume $V_2$ is found by integrating these expressions:

$$

W_\text{by} = \int_{V_1}^{V_2} P dV \quad \text{and} \quad W_\text{on} = -\int_{V_1}^{V_2} P dV

$$

The magnitude of this work is graphically represented by the area under the curve on a P-V diagram.

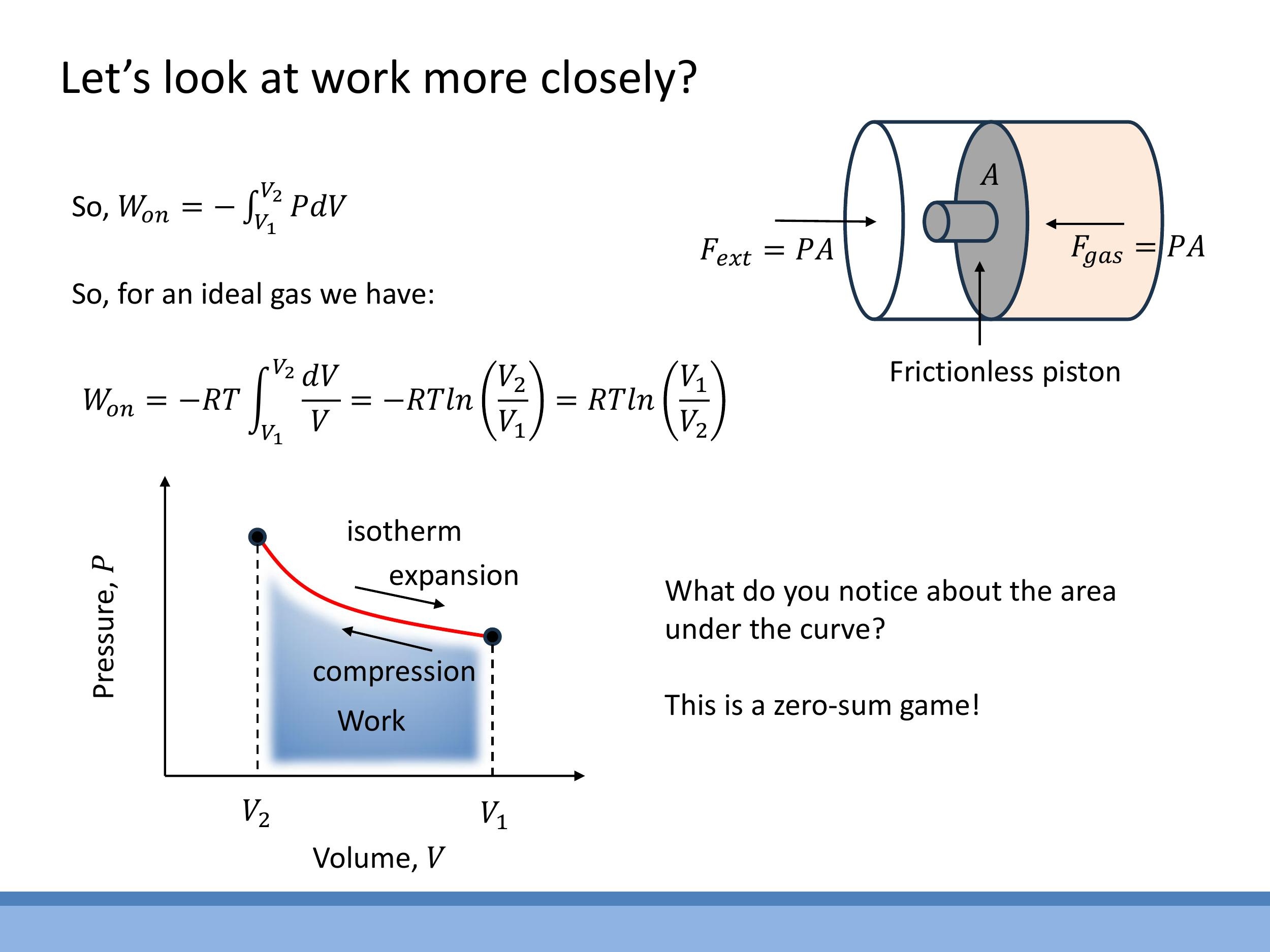

3) Isothermal work for an ideal gas and what the area means

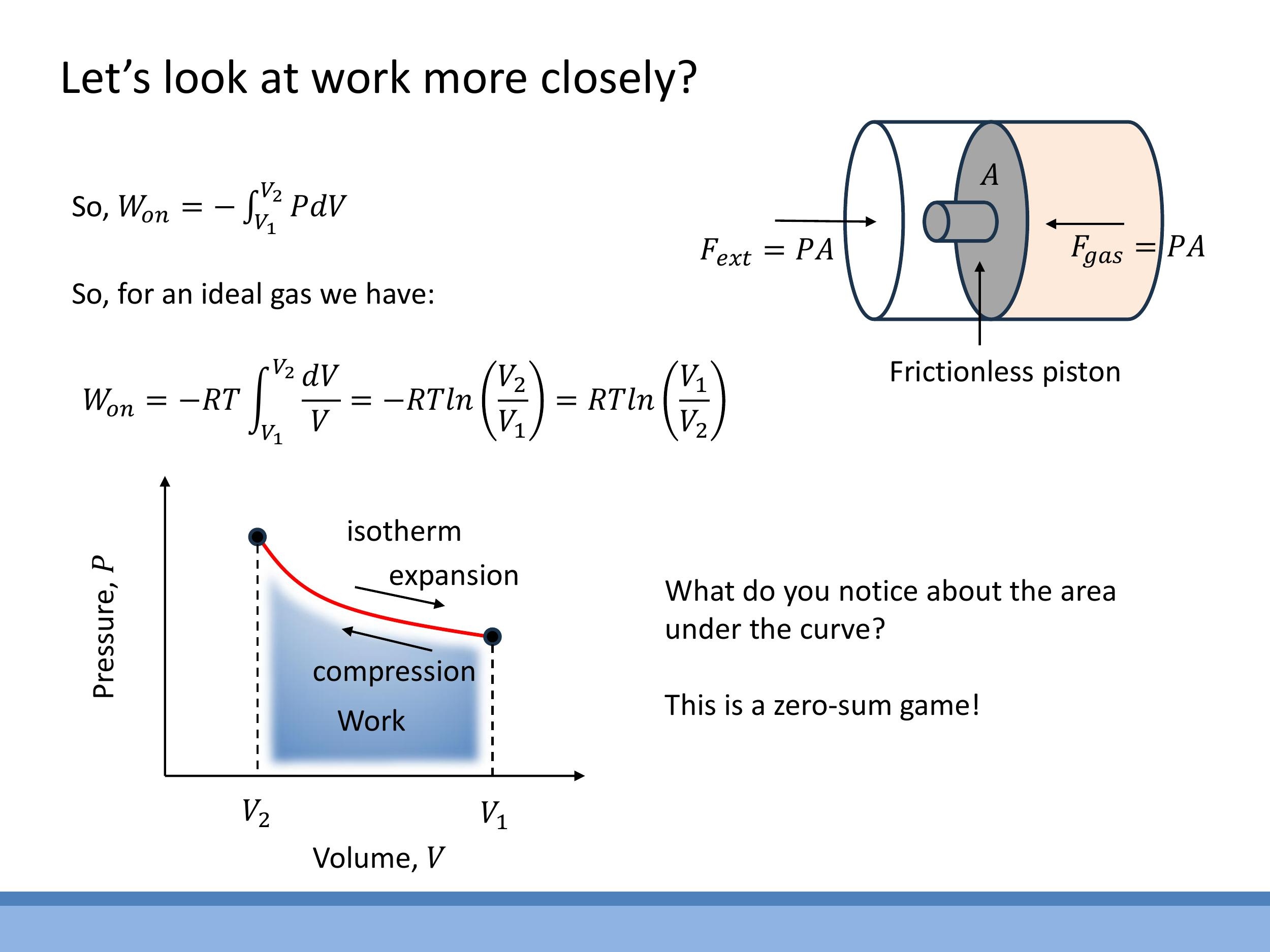

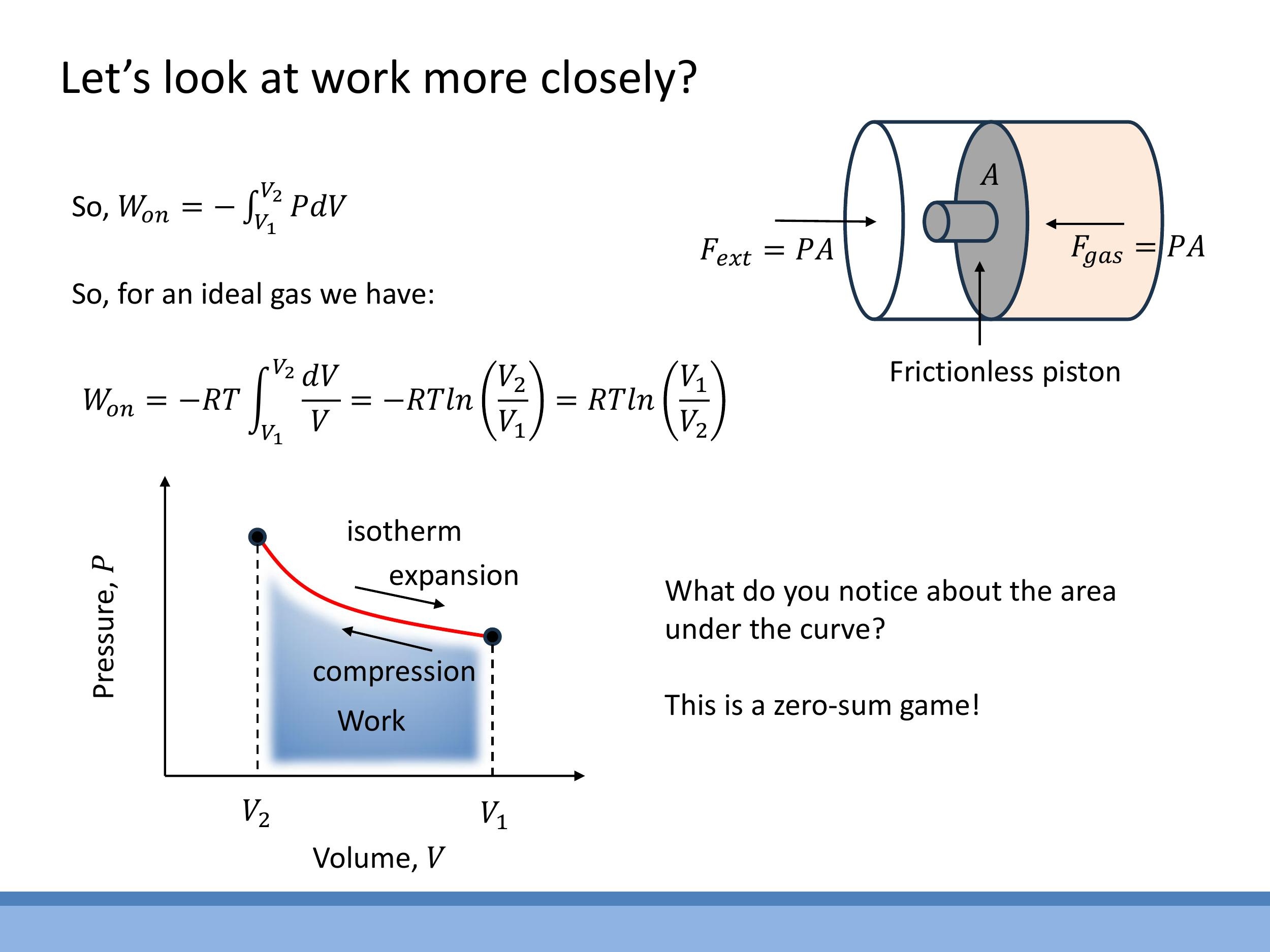

When an ideal gas undergoes an isothermal process, its temperature $T$ remains constant. For one mole of an ideal gas, the ideal gas law states $P = RT/V$. We can use this to calculate the work done during an isothermal compression from $V_1$ to $V_2$. The work done on the gas is:

$$

W_\text{on} = -\int_{V_1}^{V_2} P dV = -\int_{V_1}^{V_2} \frac{RT}{V} dV

$$

Since $R$ and $T$ are constant for an isothermal process, they can be taken out of the integral:

$$W_\text{on} = -RT \int_{V_1}^{V_2} \frac{1}{V} dV = -RT \left[ \ln(V) \right] {V_1}^{V_2} = -RT \ln\left(\frac{V_2}{V_1}\right)$$

Using the property of logarithms, $\ln(a/b) = -\ln(b/a)$, this can also be written as:

$$W \text{on} = RT \ln\left(\frac{V_1}{V_2}\right) $$

Let's consider a worked example. If $1 \, \text{mol} $ of an ideal gas at $ 23 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ (approximately $ 300 \, \text{K} $) is compressed by a factor of $ 2 $ (so $ V_1/V_2 = 2$), the work done on the gas is:

$$

W_\text{on} \approx (8.314\,\text{J mol}^{-1}\text{K}^{-1}) (300\,\text{K}) \ln(2) \approx 1.7 \times 10^3\,\text{J}

$$

⚠️ Exam Alert! The lecturer explicitly stated: "This is not so difficult but not so different to the kind of question that you might get in the multiple choice test in December. It's not so different. Something like this, I've asked before." Students should be prepared for calculations of this nature.

On a P-V diagram, an isotherm is a hyperbolic curve. The area under this curve represents the work done. If a gas expands isothermally and then is compressed isothermally back along the same curve, the total net work done is zero. This illustrates that a simple back-and-forth isothermal process yields no net useful work.

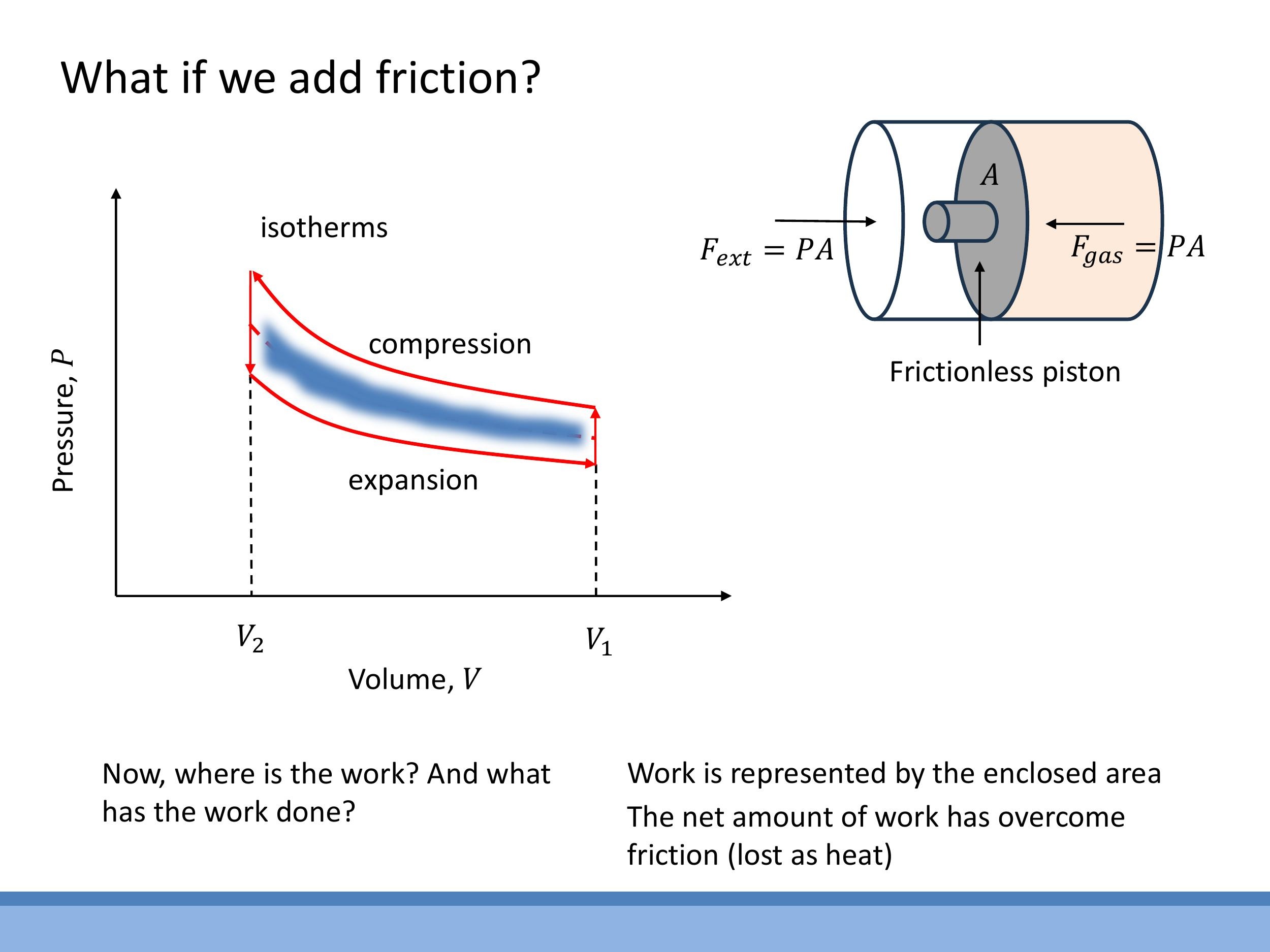

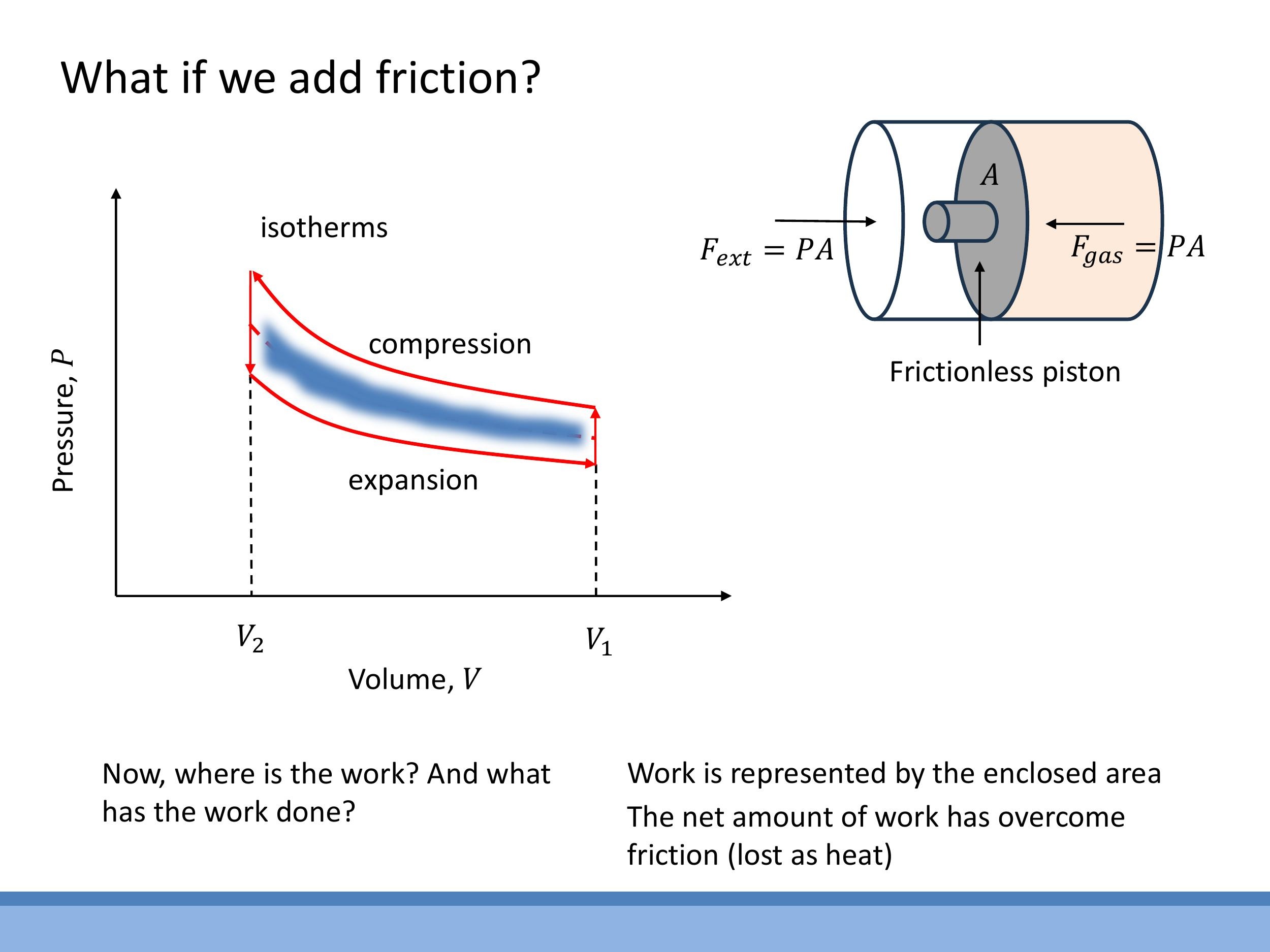

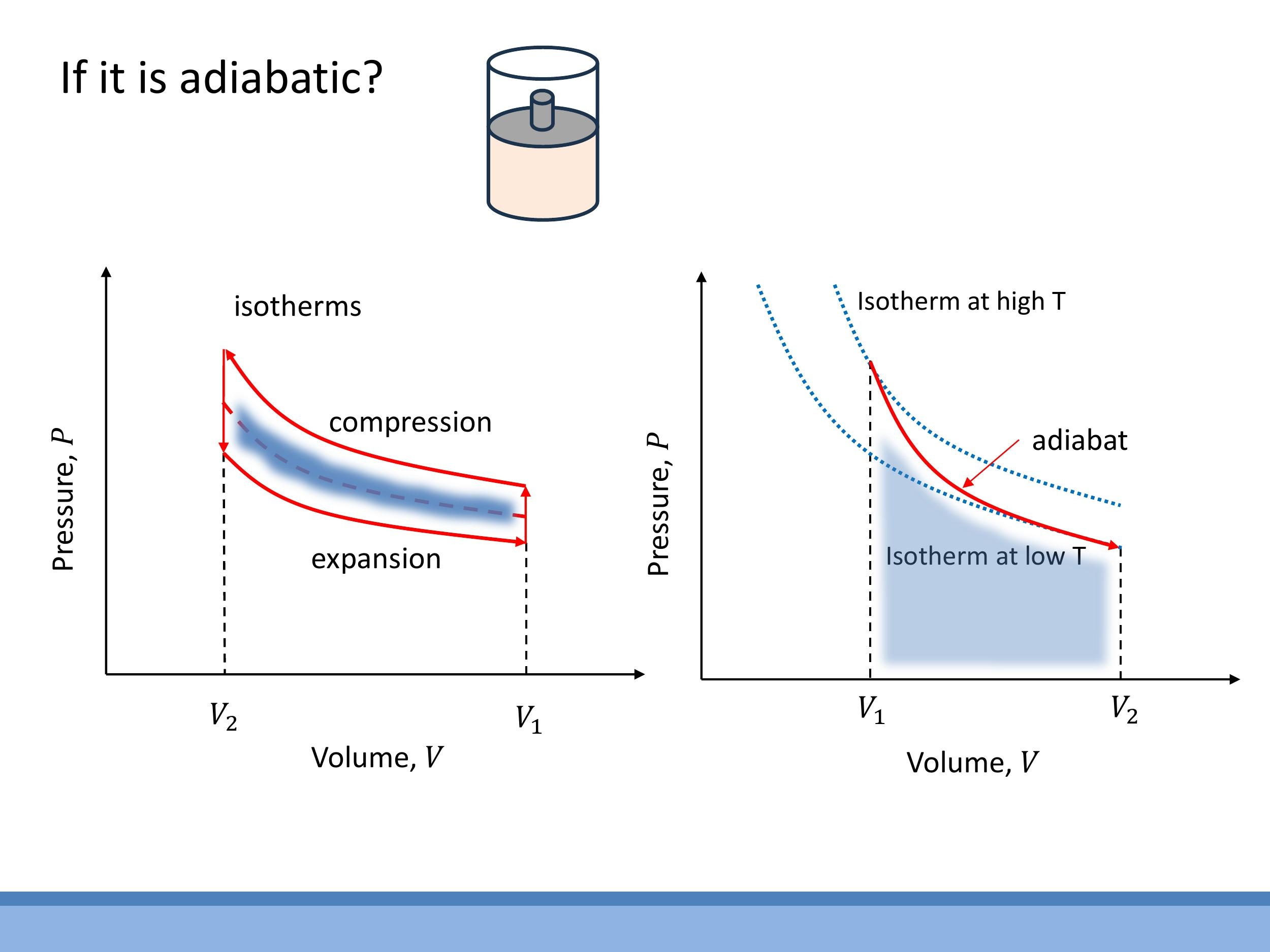

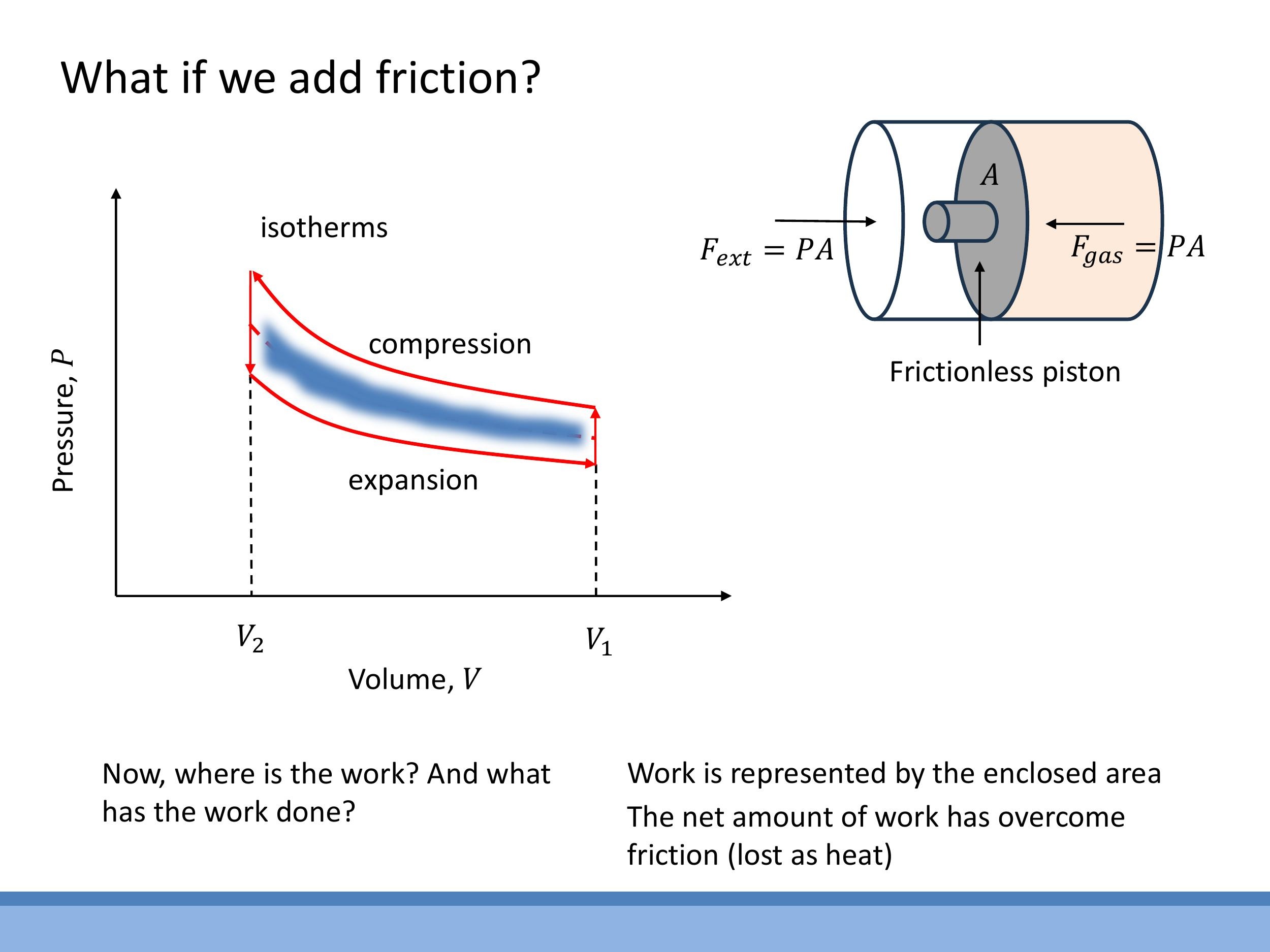

4) Adding friction: why loops appear and where the work goes

In real-world systems, friction is always present, making processes irreversible. When friction is involved, the compression and expansion of a gas no longer follow the same path on a P-V diagram. Instead, they form a closed loop. The area enclosed by this loop represents the net work done during the cycle. This work, however, is not useful output; it is dissipated as heat, overcoming the frictional forces. This highlights why reversibility is an ideal goal: it's the route to extracting the maximum amount of useful work from a thermodynamic process.

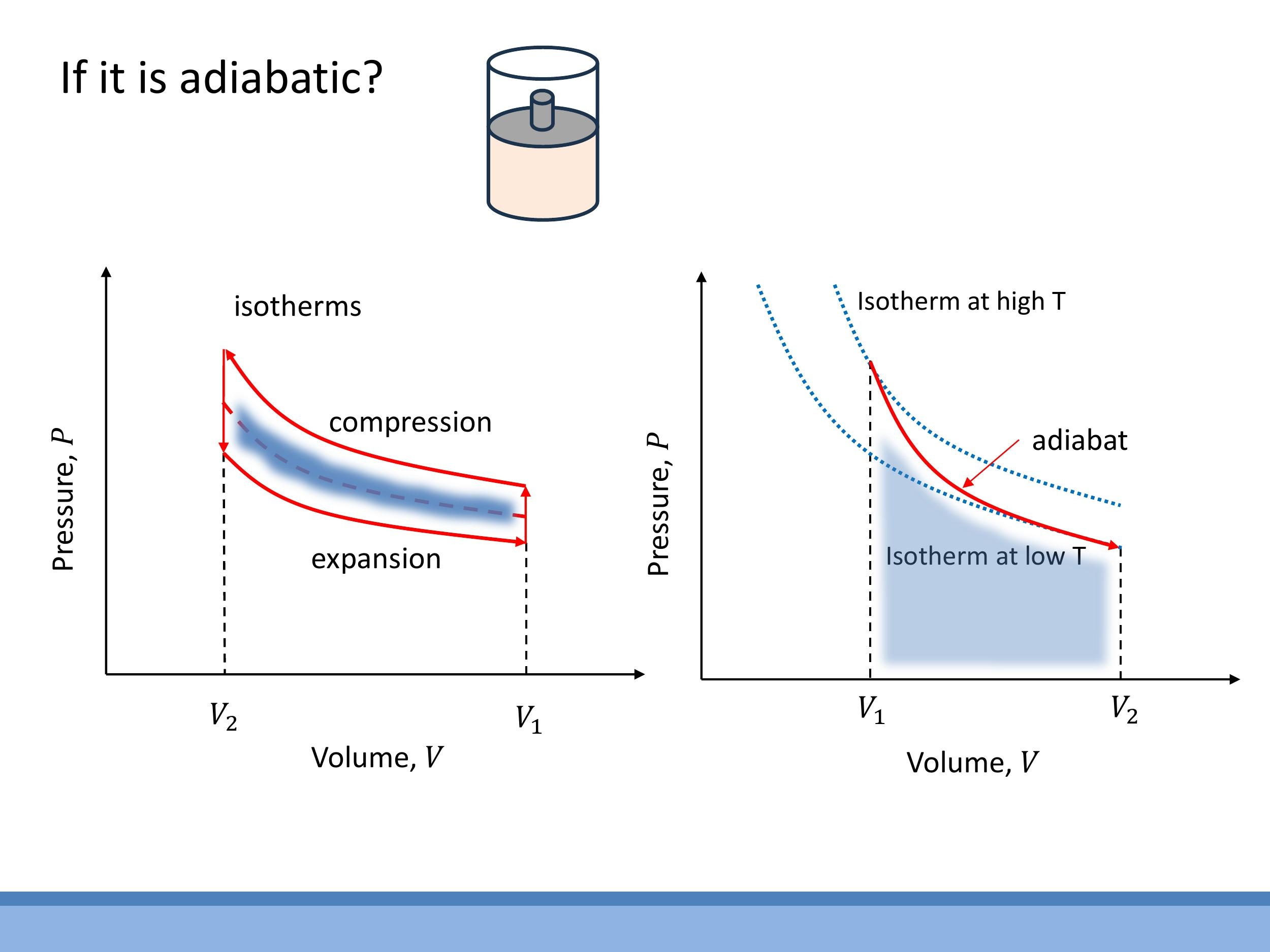

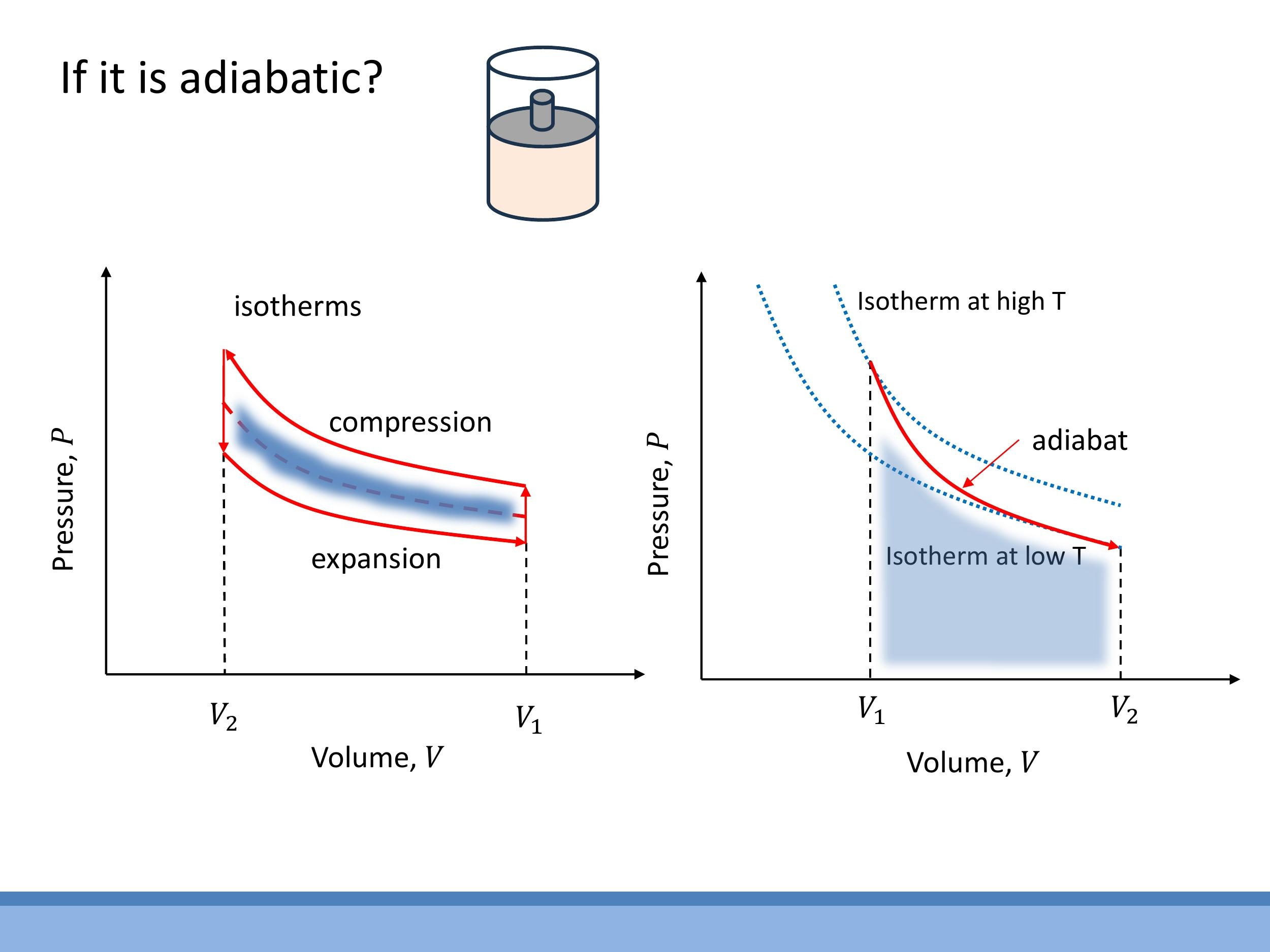

5) Adiabatic processes: definition and P-V shape

An adiabatic process is defined by the absence of heat exchange with the surroundings, meaning $dQ = 0$. Such processes are often approximated by rapid changes in a system or by systems that are extremely well insulated.

On a P-V diagram, an adiabatic process is represented by a curve called an adiabat. Unlike an isotherm, the temperature of the gas changes along an adiabat. Adiabatic curves are noticeably steeper than isotherms. This means that during an adiabatic compression, the gas heats up, moving to higher-temperature isotherms. Conversely, during an adiabatic expansion, the gas cools down, moving to lower-temperature isotherms. The internal energy of the system changes directly due to the work done on or by the gas, without any compensating heat flow.

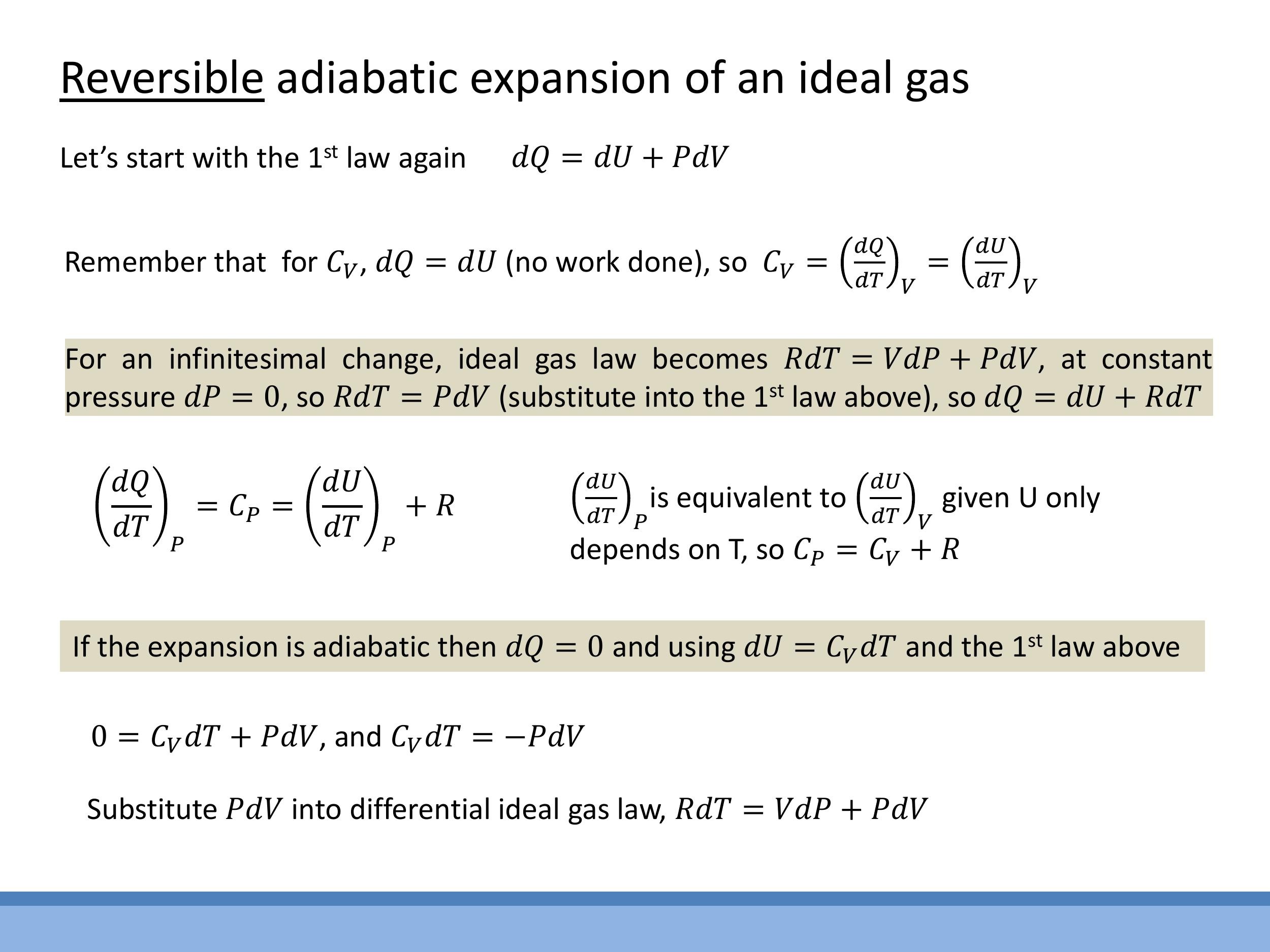

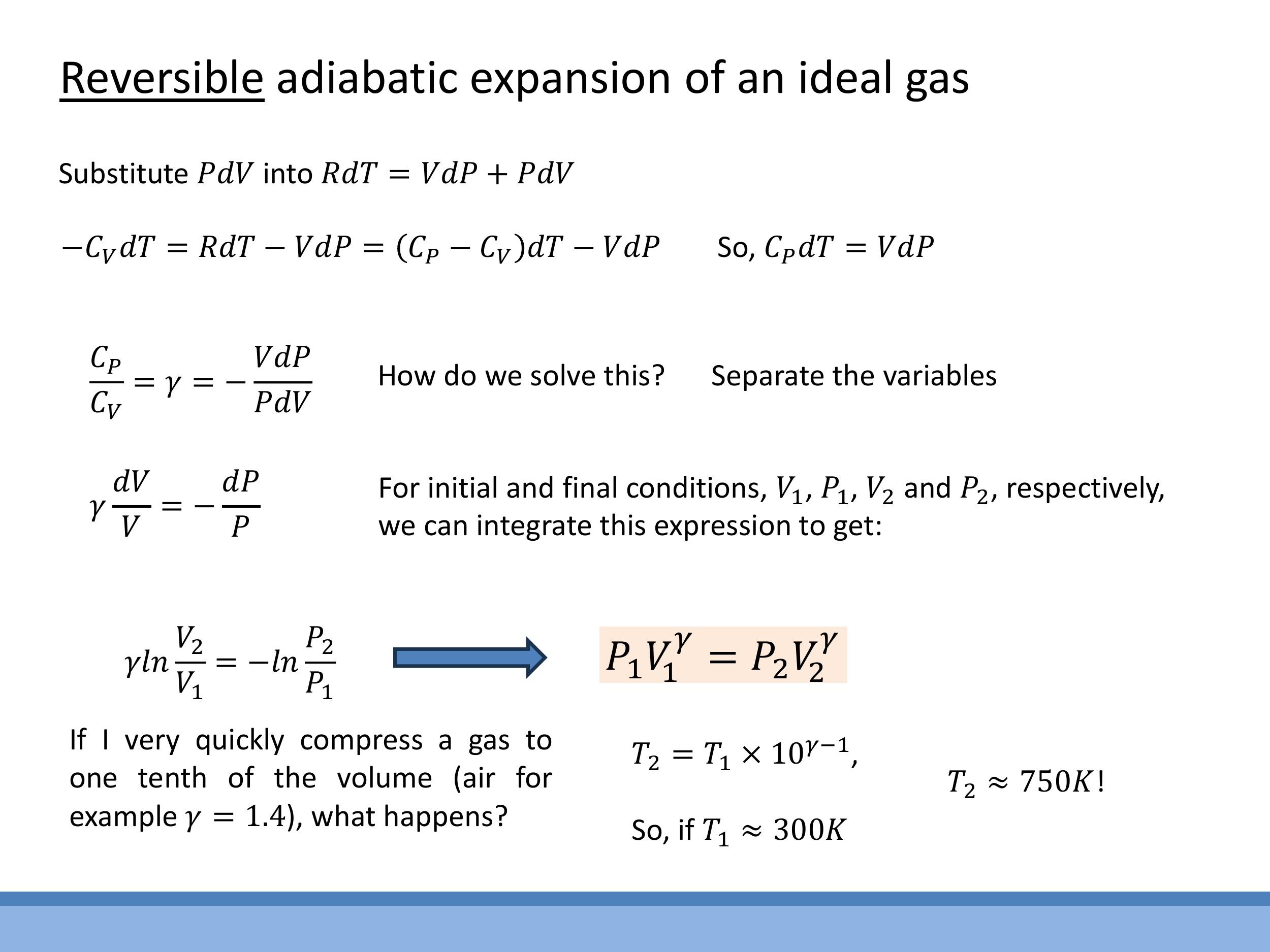

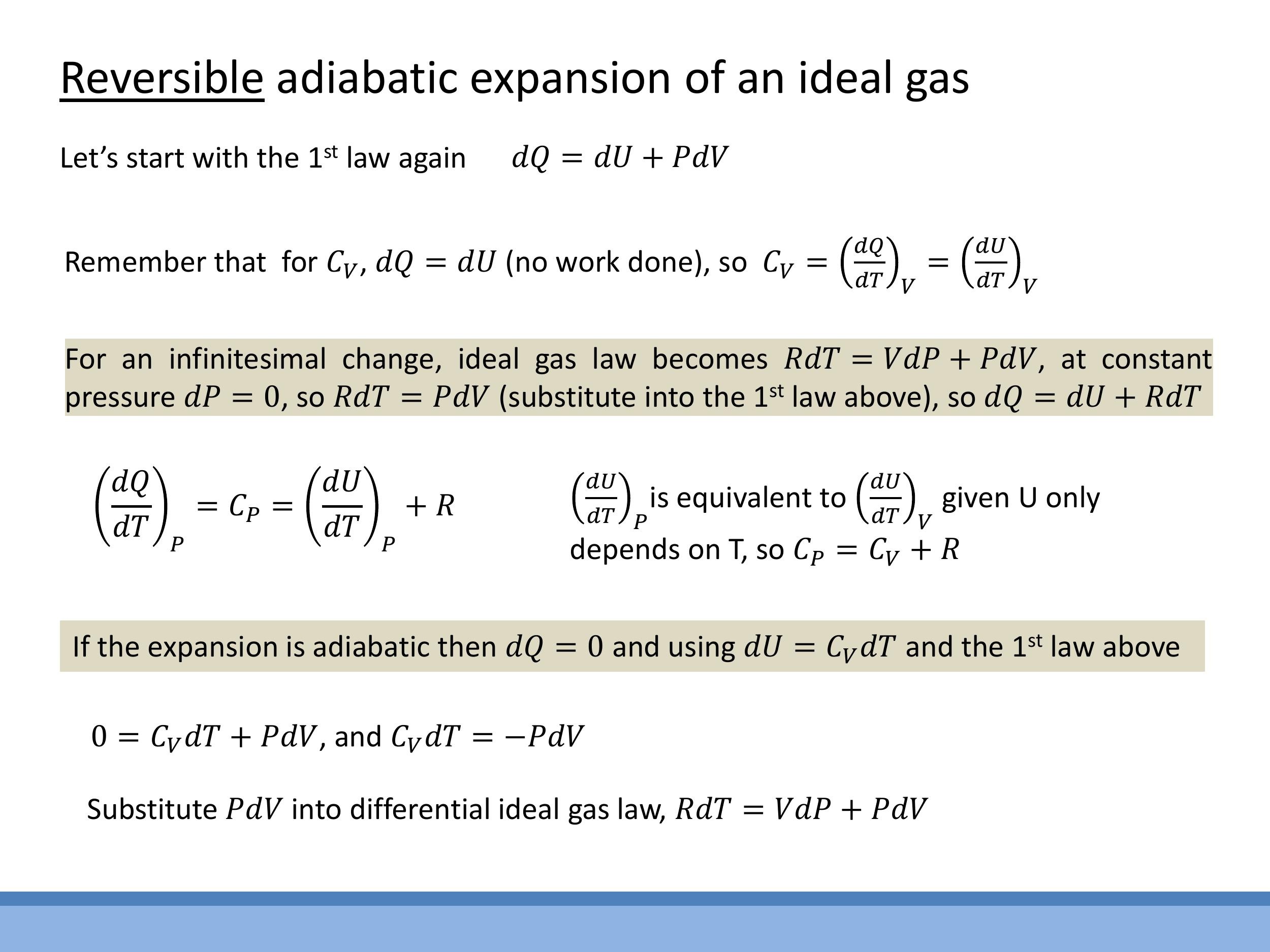

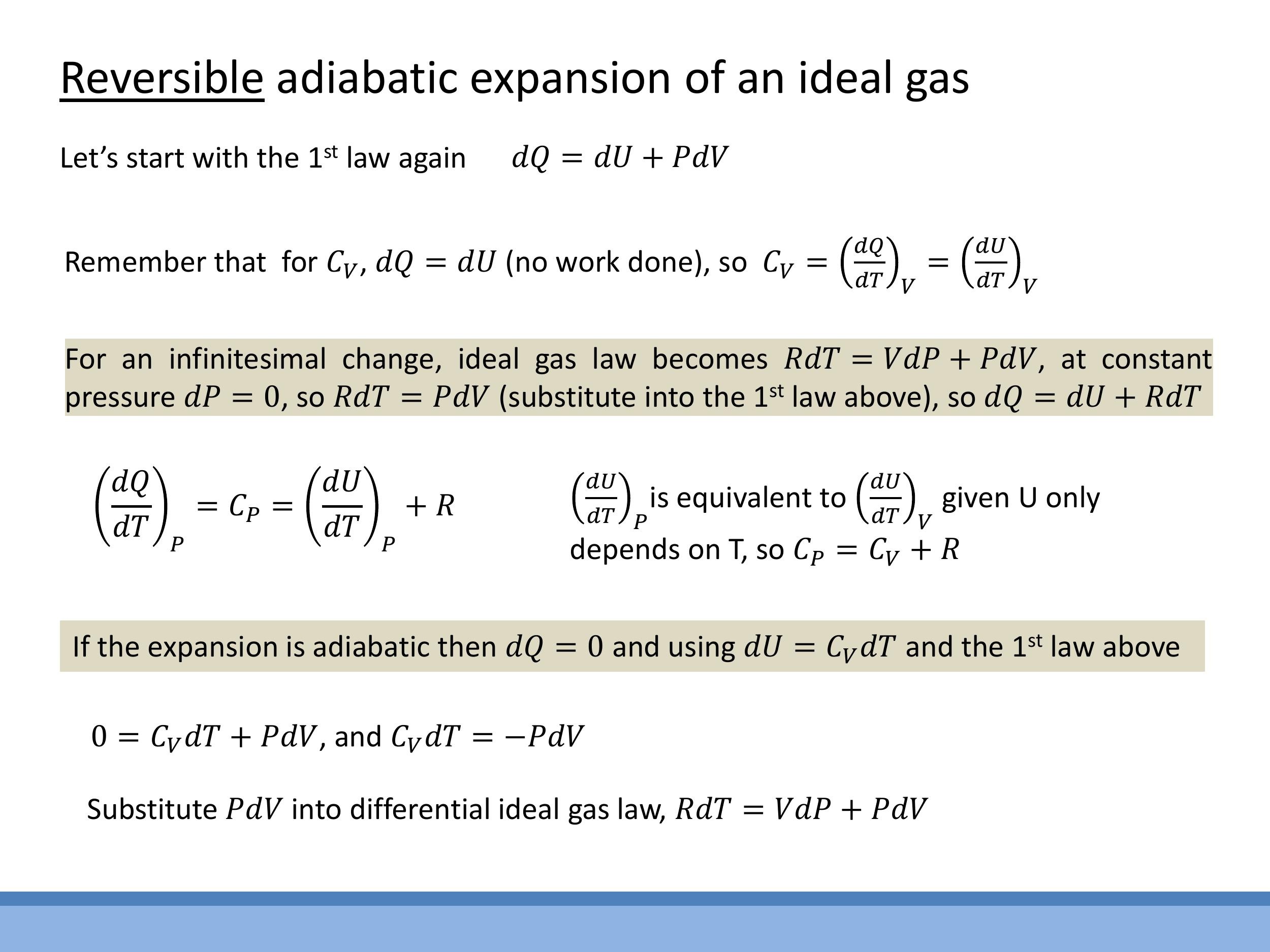

6) Deriving the reversible adiabatic relation PV^γ = constant

Let's derive the fundamental relationship for a reversible adiabatic process involving an ideal gas. We'll start with the First Law of Thermodynamics in the form $dQ = dU + PdV$. Since the process is adiabatic, $dQ = 0$, so we have:

$$

0 = dU + PdV

$$

For an ideal gas, the change in internal energy $dU$ is given by $dU = C_V dT$, where $C_V$ is the molar specific heat capacity at constant volume. Substituting this into the First Law yields:

$$

C_V dT = -PdV

$$

We also use the differential form of the ideal gas law (for one mole), $R dT = V dP + P dV$, and Mayer's relation, $R = C_P - C_V$, where $C_P$ is the molar specific heat capacity at constant pressure.

We can combine these equations. From $C_V dT = -PdV$, we can substitute $PdV$ into the differential ideal gas law:

$$

(C_P - C_V)dT = VdP + PdV

$$

$$

(C_P - C_V)dT = VdP - C_V dT

$$

Rearranging this, the $-C_V dT$ terms cancel, leaving:

$$

C_P dT = V dP

$$

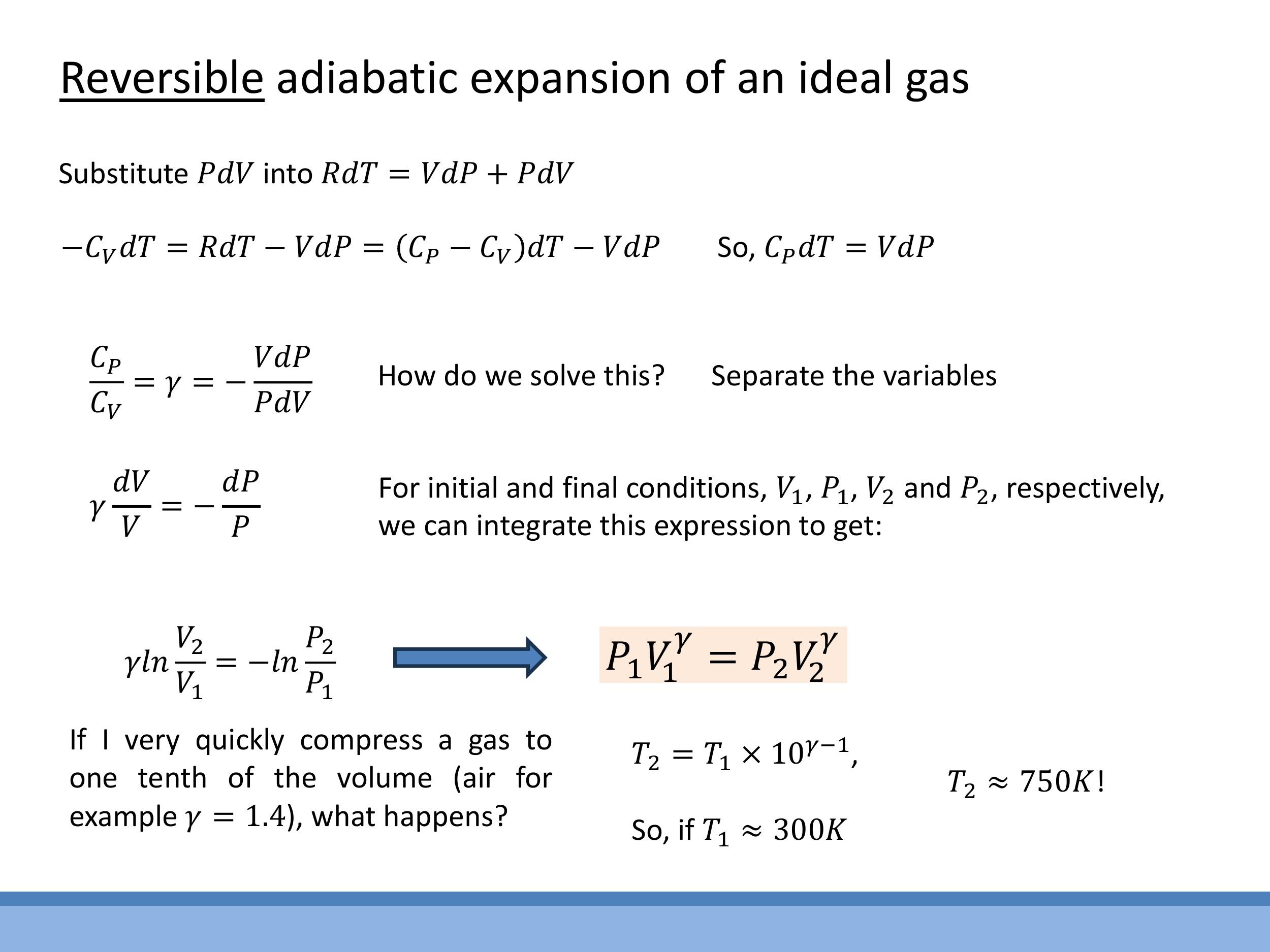

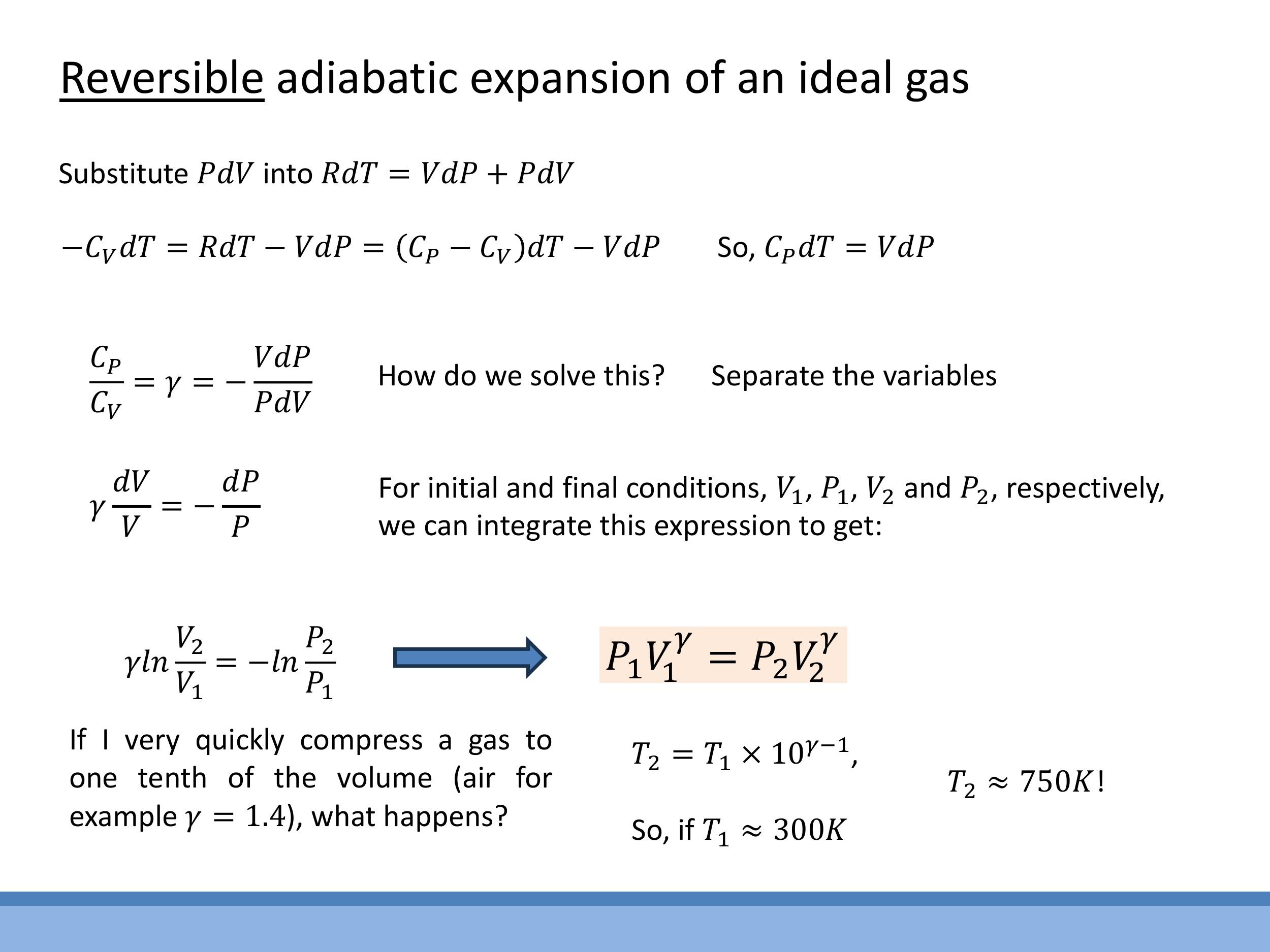

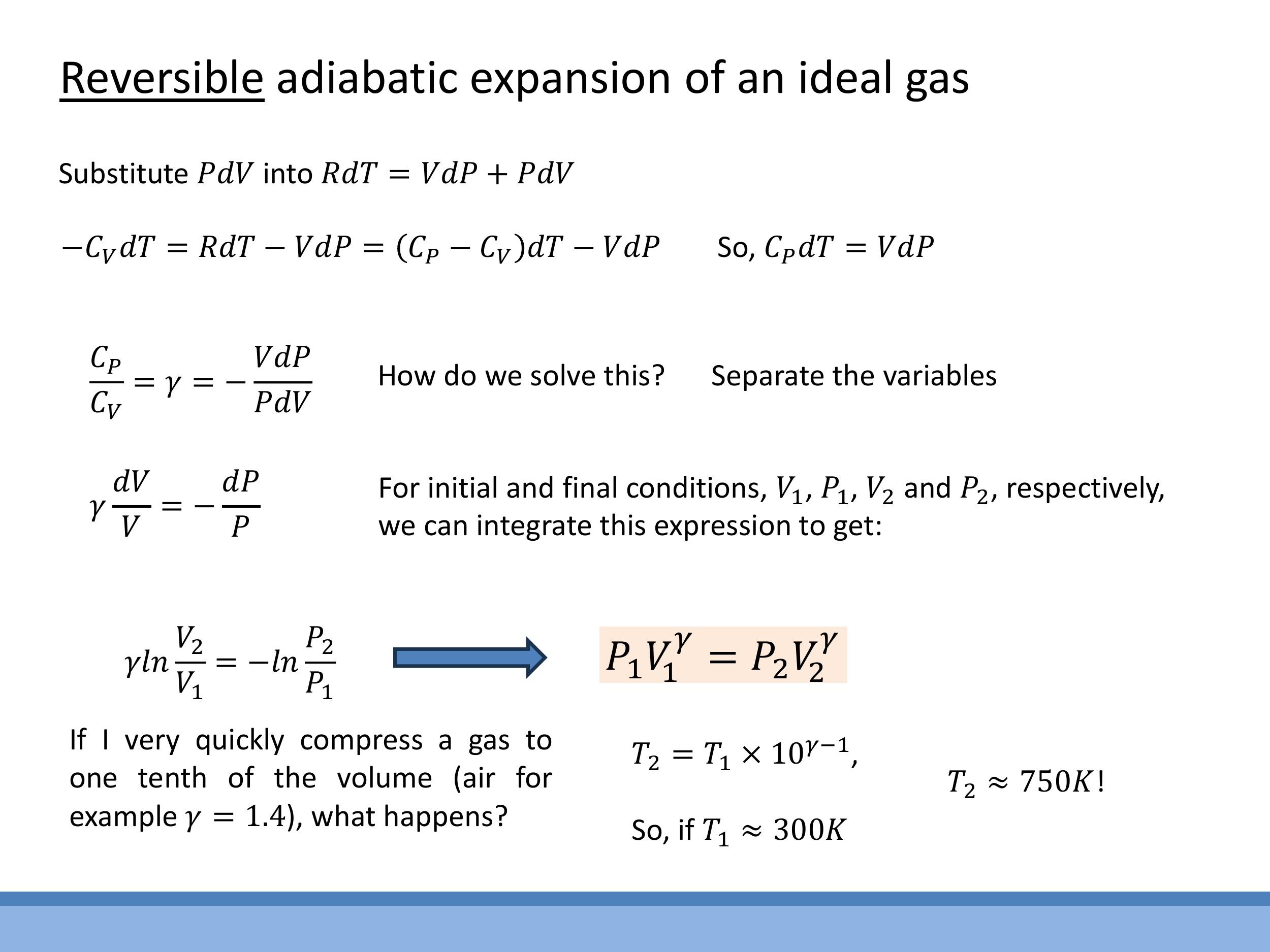

Now we have two key linear relations: $C_V dT = -PdV$ and $C_P dT = V dP$. If we divide the second equation by the first, the $dT$ terms cancel:

$$

\frac{C_P}{C_V} = \frac{V dP}{-P dV}

$$

We define $\gamma \equiv C_P/C_V$, which is the ratio of specific heats. So, we have:

$$

\gamma = -\frac{V}{P} \frac{dP}{dV}

$$

To solve this, we separate the variables:

$$

\gamma \frac{dV}{V} = -\frac{dP}{P}

$$

Integrating both sides from an initial state $(P_1, V_1)$ to a final state $(P_2, V_2)$:

$$

\int_{V_1}^{V_2} \gamma \frac{dV}{V} = -\int_{P_1}^{P_2} \frac{dP}{P}

$$

$$\gamma [\ln V] {V_1}^{V_2} = -[\ln P] {P_1}^{P_2} $$

$$

\gamma \ln\left(\frac{V_2}{V_1}\right) = -\ln\left(\frac{P_2}{P_1}\right)

$$

Using logarithm properties, this leads to the fundamental reversible adiabatic relation:

$$

P_1 V_1^\gamma = P_2 V_2^\gamma = \text{constant}

$$

The value of $\gamma$ depends on the type of gas. For monatomic ideal gases, $\gamma = 5/3 \approx 1.67$. For diatomic gases like air at room temperature, $\gamma \approx 1.4$.

7) Temperature-volume relation for adiabatic processes

From the adiabatic relation $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$, we can derive a similar relationship between temperature and volume. For one mole of an ideal gas, we know $P = RT/V$. Substituting this into the adiabatic equation gives:

$$

\left(\frac{RT}{V}\right) V^\gamma = \text{constant}

$$

$$

RT V^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}

$$

Since $R$ is a constant, we can absorb it into the overall constant, leading to:

$$

TV^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}

$$

This means that for two states $(T_1, V_1)$ and $(T_2, V_2)$ in a reversible adiabatic process:

$$

T_1 V_1^{\gamma-1} = T_2 V_2^{\gamma-1}

$$

This relationship is particularly useful for quickly estimating temperature changes during adiabatic compression or expansion. The exponent $\gamma-1$ directly controls how much the temperature rises upon compression or falls upon expansion.

8) Application: adiabatic compression in the diesel engine (+ live demo)

The principle of adiabatic compression is central to how a diesel engine operates. Air is rapidly compressed to such a high temperature that when fuel is injected, it ignites spontaneously without the need for a spark plug.

Let's estimate the temperature increase for a typical diesel engine scenario. If air (a diatomic gas, so $\gamma \approx 1.4$) at room temperature ($T_1 \approx 300 \, \text{K} $) is compressed to one-tenth of its original volume ($ V_1/V_2 = 10 $), we can use the $ T $-$ V$ relation:

$$

T_2 = T_1 \left(\frac{V_1}{V_2}\right)^{\gamma-1}

$$

$$

T_2 = 300\,\text{K} \times (10)^{(1.4 - 1)} = 300\,\text{K} \times 10^{0.4}

$$

$$

T_2 \approx 300\,\text{K} \times 2.5 \approx 750\,\text{K}

$$

This corresponds to approximately $480 \, ^\circ\text{C} $. Real diesel engines often have compression ratios closer to $ 16:1$, resulting in even higher temperatures.

This effect can be dramatically demonstrated using a "fire piston." The setup involves a transparent cylinder containing air and a small piece of cotton wool. When the piston is compressed very rapidly, the air inside heats up quickly, approximating an adiabatic process. The temperature rise is sufficient to ignite the cotton wool, causing it to flash brightly. This visual proof directly illustrates the significant temperature increase achieved through adiabatic compression, which is the core physics behind the diesel engine.

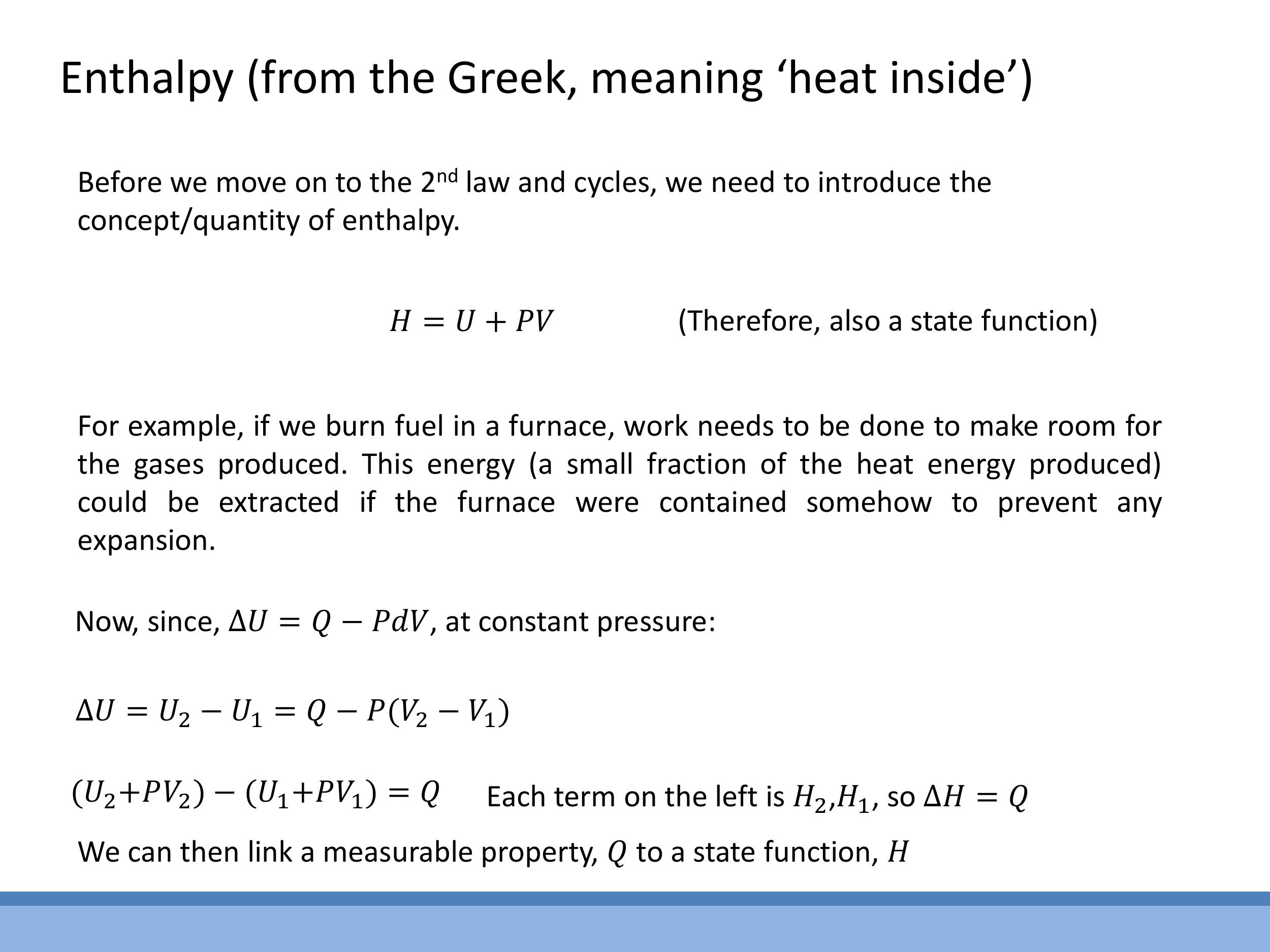

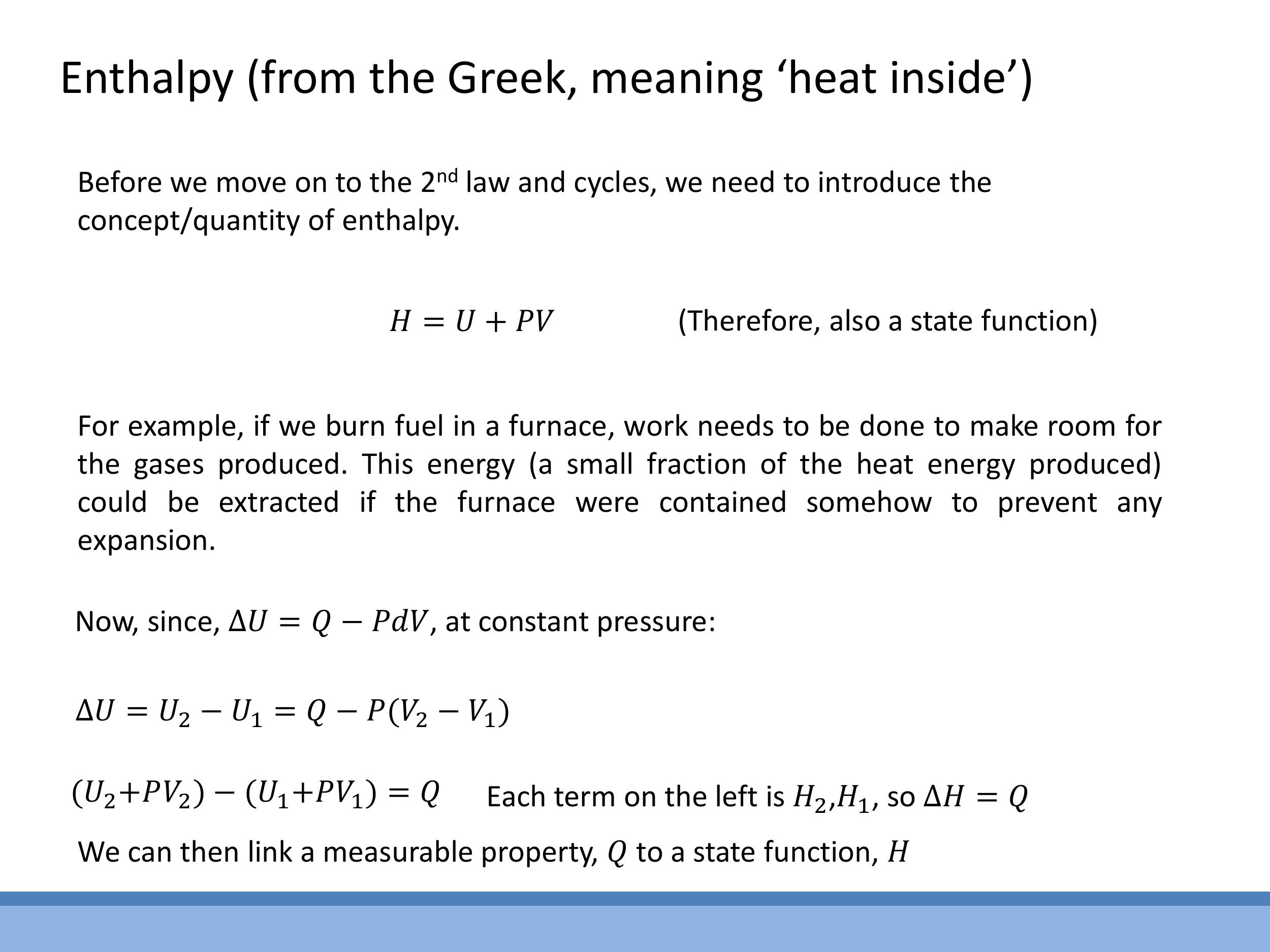

9) Introduction to enthalpy: H = U + PV

To prepare for future discussions on the Second Law of Thermodynamics and thermodynamic cycles, we introduce a new thermodynamic state function called enthalpy, $H$. It is defined as:

$$

H \equiv U + PV

$$

where $U$ is the internal energy, $P$ is the pressure, and $V$ is the volume. Since $U$, $P$, and $V$ are all state functions, enthalpy $H$ is also a state function.

Enthalpy is particularly useful for processes occurring at constant pressure. If a system undergoes a change at constant pressure, the heat transferred $Q$ is equal to the change in enthalpy, $\Delta H = Q$. This relationship is very convenient because it links a measurable quantity (heat transferred) to a state function, simplifying the analysis of systems where volume changes occur, such as in open systems or when burning fuel. We'll use enthalpy extensively when analysing thermodynamic cycles and the Second Law in upcoming lectures.

Key takeaways

Reversibility in thermodynamics refers to idealised, quasi-static processes that are responsive to infinitesimal changes and can extract maximum useful work, leaving the total entropy of the universe unchanged. Most everyday processes are irreversible. The work done by a gas during expansion is $dW_\text{by} = P dV$, while work done on the gas during compression is $dW_\text{on} = -P dV$. The area under the P-V curve represents the work done. A simple isothermal expansion and compression along the same path results in no net useful work. In the presence of friction, compression and expansion paths diverge, forming a loop on the P-V diagram; the enclosed area represents work lost as heat due to irreversibility.

Adiabatic processes involve no heat exchange ($dQ = 0$) and are typically embodied by rapid or well-insulated changes. These processes cause temperature changes and are represented by steeper curves (adiabats) on a P-V diagram compared to isotherms. For a reversible adiabatic process in an ideal gas, we derive the fundamental relations:

$$

P V^\gamma = \text{constant}

$$

and

$$

T V^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}

$$

where $\gamma = C_P/C_V$. For diatomic gases like air at room temperature, $\gamma \approx 1.4$. This principle is crucial for the diesel engine, where rapid, near-adiabatic compression raises the air temperature sufficiently to ignite fuel without a spark. For example, a tenfold volume reduction from $300 \, \text{K} $ can increase the temperature to approximately $ 750 \, \text{K}$.

Finally, enthalpy, defined as $H = U + PV$, is a state function that simplifies the analysis of constant-pressure processes, where the heat transferred $Q$ is equal to the change in enthalpy, $\Delta H$. This concept will be vital for understanding thermodynamic cycles and the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

## Lecture 10: Reversible Processes and Adiabatic Expansion (Diesel Engine)

### 0) Orientation, admin, and quick review

This lecture builds on previous discussions of the First Law of Thermodynamics, alongside concepts of work, heat, and ideal gas differentials. Today, we'll delve into distinguishing between reversible and irreversible processes and calculating work for isothermal and adiabatic changes. We'll derive and apply the adiabatic relations, $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$ and $TV^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}$, and see how adiabatic compression applies to the diesel engine. Finally, we'll introduce enthalpy, $H = U + PV$, a concept that will be crucial for understanding later thermodynamic cycles and the Second Law.

Before we begin, a student research project is inviting participation to gather feedback on first-year physics learning. This is an optional, extra-curricular opportunity, and details for signing up will be available after the lecture.

As a quick recap, remember that internal energy $U$ is a state function, meaning its value depends only on the system's current state, not on the path taken to reach it. In contrast, heat $Q$ and work $W$ are processes of energy transfer. Throughout this course, we primarily use the differential form of the First Law: $dQ = dU + PdV$, where $PdV$ represents the work done *by* the system. This convention helps us in deriving relationships for various thermodynamic processes.

### 1) What thermodynamic reversibility really means

To understand thermodynamic efficiency, it's crucial to grasp the concept of reversibility. Many everyday processes are, in fact, thermodynamically irreversible. Consider a hot iron block cooling in room air, a chemical reaction, a steady current flowing through a wire, or fuel burning in an engine. In all these cases, a minuscule change in the surroundings won't reverse the process. For instance, if a $100\,^\circ\text{C}$ block is cooling, a tiny $0.1\,^\circ\text{C}$ increase in the ambient air temperature won't cause the block to start heating up again.

An ideal reversible process operates under very specific, idealised conditions. The system must remain in thermodynamic equilibrium throughout the entire process, meaning its macroscopic properties are unchanging. Such a process is reversible to infinitesimal changes in any property; a tiny alteration in the surroundings can flip the direction of the change. A reversible process is also one that extracts the maximum possible useful work from a system. Importantly, for a reversible process, the total entropy of the universe (the system plus its surroundings) remains unchanged. While a full treatment of entropy will come later, it's useful to think of it here as a measure of disorder.

The frictionless piston model provides a good physical anchor for understanding reversibility. Imagine a piston moving freely within a cylinder, in equilibrium with a heat reservoir. If the temperature of the heat reservoir is increased infinitesimally, the piston will move slightly upwards. Conversely, a tiny decrease in the reservoir's temperature will cause the piston to move slightly downwards. This sensitivity to infinitesimal changes in either direction is a hallmark of a reversible process.

### 2) Work in P-V processes: from forces to dW = PdV

To understand energy transformations in gases, we need to precisely define the work done during changes in volume. When a gas expands, it does work *by* the system. Consider a piston moving outwards by an infinitesimal distance $dx$. The force exerted by the gas is $F_\text{gas} = PA$, where $P$ is the pressure and $A$ is the piston's cross-sectional area. The infinitesimal work done by the gas, $dW_\text{by}$, is $F_\text{gas} dx = P A dx$. Since $A dx$ is the infinitesimal change in volume, $dV$, we can write:

$$dW_\text{by} = P dV$$

Conversely, if we compress the gas, work is done *on* the system. In this case, the piston moves inwards, so the change in volume $dV$ is negative. The work done *on* the gas, $dW_\text{on}$, is given by:

$$dW_\text{on} = -P dV$$

The total work done along a path from an initial volume $V_1$ to a final volume $V_2$ is found by integrating these expressions:

$$W_\text{by} = \int_{V_1}^{V_2} P dV \quad \text{and} \quad W_\text{on} = -\int_{V_1}^{V_2} P dV$$

The magnitude of this work is graphically represented by the area under the curve on a P-V diagram.

### 3) Isothermal work for an ideal gas and what the area means

When an ideal gas undergoes an isothermal process, its temperature $T$ remains constant. For one mole of an ideal gas, the ideal gas law states $P = RT/V$. We can use this to calculate the work done during an isothermal compression from $V_1$ to $V_2$. The work done *on* the gas is:

$$W_\text{on} = -\int_{V_1}^{V_2} P dV = -\int_{V_1}^{V_2} \frac{RT}{V} dV$$

Since $R$ and $T$ are constant for an isothermal process, they can be taken out of the integral:

$$W_\text{on} = -RT \int_{V_1}^{V_2} \frac{1}{V} dV = -RT \left[ \ln(V) \right]_{V_1}^{V_2} = -RT \ln\left(\frac{V_2}{V_1}\right)$$

Using the property of logarithms, $\ln(a/b) = -\ln(b/a)$, this can also be written as:

$$W_\text{on} = RT \ln\left(\frac{V_1}{V_2}\right)$$

Let's consider a worked example. If $1\,\text{mol}$ of an ideal gas at $23\,^\circ\text{C}$ (approximately $300\,\text{K}$) is compressed by a factor of $2$ (so $V_1/V_2 = 2$), the work done *on* the gas is:

$$W_\text{on} \approx (8.314\,\text{J mol}^{-1}\text{K}^{-1}) (300\,\text{K}) \ln(2) \approx 1.7 \times 10^3\,\text{J}$$

> **⚠️ Exam Alert!** The lecturer explicitly stated: "This is not so difficult but not so different to the kind of question that you might get in the multiple choice test in December. It's not so different. Something like this, I've asked before." Students should be prepared for calculations of this nature.

On a P-V diagram, an isotherm is a hyperbolic curve. The area under this curve represents the work done. If a gas expands isothermally and then is compressed isothermally back along the same curve, the total net work done is zero. This illustrates that a simple back-and-forth isothermal process yields no net useful work.

### 4) Adding friction: why loops appear and where the work goes

In real-world systems, friction is always present, making processes irreversible. When friction is involved, the compression and expansion of a gas no longer follow the same path on a P-V diagram. Instead, they form a closed loop. The area enclosed by this loop represents the net work done during the cycle. This work, however, is not useful output; it is dissipated as heat, overcoming the frictional forces. This highlights why reversibility is an ideal goal: it's the route to extracting the maximum amount of useful work from a thermodynamic process.

### 5) Adiabatic processes: definition and P-V shape

An adiabatic process is defined by the absence of heat exchange with the surroundings, meaning $dQ = 0$. Such processes are often approximated by rapid changes in a system or by systems that are extremely well insulated.

On a P-V diagram, an adiabatic process is represented by a curve called an adiabat. Unlike an isotherm, the temperature of the gas changes along an adiabat. Adiabatic curves are noticeably steeper than isotherms. This means that during an adiabatic compression, the gas heats up, moving to higher-temperature isotherms. Conversely, during an adiabatic expansion, the gas cools down, moving to lower-temperature isotherms. The internal energy of the system changes directly due to the work done on or by the gas, without any compensating heat flow.

### 6) Deriving the reversible adiabatic relation PV^γ = constant

Let's derive the fundamental relationship for a reversible adiabatic process involving an ideal gas. We'll start with the First Law of Thermodynamics in the form $dQ = dU + PdV$. Since the process is adiabatic, $dQ = 0$, so we have:

$$0 = dU + PdV$$

For an ideal gas, the change in internal energy $dU$ is given by $dU = C_V dT$, where $C_V$ is the molar specific heat capacity at constant volume. Substituting this into the First Law yields:

$$C_V dT = -PdV$$

We also use the differential form of the ideal gas law (for one mole), $R dT = V dP + P dV$, and Mayer's relation, $R = C_P - C_V$, where $C_P$ is the molar specific heat capacity at constant pressure.

We can combine these equations. From $C_V dT = -PdV$, we can substitute $PdV$ into the differential ideal gas law:

$$(C_P - C_V)dT = VdP + PdV$$

$$(C_P - C_V)dT = VdP - C_V dT$$

Rearranging this, the $-C_V dT$ terms cancel, leaving:

$$C_P dT = V dP$$

Now we have two key linear relations: $C_V dT = -PdV$ and $C_P dT = V dP$. If we divide the second equation by the first, the $dT$ terms cancel:

$$\frac{C_P}{C_V} = \frac{V dP}{-P dV}$$

We define $\gamma \equiv C_P/C_V$, which is the ratio of specific heats. So, we have:

$$\gamma = -\frac{V}{P} \frac{dP}{dV}$$

To solve this, we separate the variables:

$$\gamma \frac{dV}{V} = -\frac{dP}{P}$$

Integrating both sides from an initial state $(P_1, V_1)$ to a final state $(P_2, V_2)$:

$$\int_{V_1}^{V_2} \gamma \frac{dV}{V} = -\int_{P_1}^{P_2} \frac{dP}{P}$$

$$\gamma [\ln V]_{V_1}^{V_2} = -[\ln P]_{P_1}^{P_2}$$

$$\gamma \ln\left(\frac{V_2}{V_1}\right) = -\ln\left(\frac{P_2}{P_1}\right)$$

Using logarithm properties, this leads to the fundamental reversible adiabatic relation:

$$P_1 V_1^\gamma = P_2 V_2^\gamma = \text{constant}$$

The value of $\gamma$ depends on the type of gas. For monatomic ideal gases, $\gamma = 5/3 \approx 1.67$. For diatomic gases like air at room temperature, $\gamma \approx 1.4$.

### 7) Temperature-volume relation for adiabatic processes

From the adiabatic relation $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$, we can derive a similar relationship between temperature and volume. For one mole of an ideal gas, we know $P = RT/V$. Substituting this into the adiabatic equation gives:

$$\left(\frac{RT}{V}\right) V^\gamma = \text{constant}$$

$$RT V^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}$$

Since $R$ is a constant, we can absorb it into the overall constant, leading to:

$$TV^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}$$

This means that for two states $(T_1, V_1)$ and $(T_2, V_2)$ in a reversible adiabatic process:

$$T_1 V_1^{\gamma-1} = T_2 V_2^{\gamma-1}$$

This relationship is particularly useful for quickly estimating temperature changes during adiabatic compression or expansion. The exponent $\gamma-1$ directly controls how much the temperature rises upon compression or falls upon expansion.

### 8) Application: adiabatic compression in the diesel engine (+ live demo)

The principle of adiabatic compression is central to how a diesel engine operates. Air is rapidly compressed to such a high temperature that when fuel is injected, it ignites spontaneously without the need for a spark plug.

Let's estimate the temperature increase for a typical diesel engine scenario. If air (a diatomic gas, so $\gamma \approx 1.4$) at room temperature ($T_1 \approx 300\,\text{K}$) is compressed to one-tenth of its original volume ($V_1/V_2 = 10$), we can use the $T$-$V$ relation:

$$T_2 = T_1 \left(\frac{V_1}{V_2}\right)^{\gamma-1}$$

$$T_2 = 300\,\text{K} \times (10)^{(1.4 - 1)} = 300\,\text{K} \times 10^{0.4}$$

$$T_2 \approx 300\,\text{K} \times 2.5 \approx 750\,\text{K}$$

This corresponds to approximately $480\,^\circ\text{C}$. Real diesel engines often have compression ratios closer to $16:1$, resulting in even higher temperatures.

This effect can be dramatically demonstrated using a "fire piston." The setup involves a transparent cylinder containing air and a small piece of cotton wool. When the piston is compressed very rapidly, the air inside heats up quickly, approximating an adiabatic process. The temperature rise is sufficient to ignite the cotton wool, causing it to flash brightly. This visual proof directly illustrates the significant temperature increase achieved through adiabatic compression, which is the core physics behind the diesel engine.

### 9) Introduction to enthalpy: H = U + PV

To prepare for future discussions on the Second Law of Thermodynamics and thermodynamic cycles, we introduce a new thermodynamic state function called enthalpy, $H$. It is defined as:

$$H \equiv U + PV$$

where $U$ is the internal energy, $P$ is the pressure, and $V$ is the volume. Since $U$, $P$, and $V$ are all state functions, enthalpy $H$ is also a state function.

Enthalpy is particularly useful for processes occurring at constant pressure. If a system undergoes a change at constant pressure, the heat transferred $Q$ is equal to the change in enthalpy, $\Delta H = Q$. This relationship is very convenient because it links a measurable quantity (heat transferred) to a state function, simplifying the analysis of systems where volume changes occur, such as in open systems or when burning fuel. We'll use enthalpy extensively when analysing thermodynamic cycles and the Second Law in upcoming lectures.

## Key takeaways

Reversibility in thermodynamics refers to idealised, quasi-static processes that are responsive to infinitesimal changes and can extract maximum useful work, leaving the total entropy of the universe unchanged. Most everyday processes are irreversible. The work done by a gas during expansion is $dW_\text{by} = P dV$, while work done on the gas during compression is $dW_\text{on} = -P dV$. The area under the P-V curve represents the work done. A simple isothermal expansion and compression along the same path results in no net useful work. In the presence of friction, compression and expansion paths diverge, forming a loop on the P-V diagram; the enclosed area represents work lost as heat due to irreversibility.

Adiabatic processes involve no heat exchange ($dQ = 0$) and are typically embodied by rapid or well-insulated changes. These processes cause temperature changes and are represented by steeper curves (adiabats) on a P-V diagram compared to isotherms. For a reversible adiabatic process in an ideal gas, we derive the fundamental relations:

$$P V^\gamma = \text{constant}$$

and

$$T V^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}$$

where $\gamma = C_P/C_V$. For diatomic gases like air at room temperature, $\gamma \approx 1.4$. This principle is crucial for the diesel engine, where rapid, near-adiabatic compression raises the air temperature sufficiently to ignite fuel without a spark. For example, a tenfold volume reduction from $300\,\text{K}$ can increase the temperature to approximately $750\,\text{K}$.

Finally, enthalpy, defined as $H = U + PV$, is a state function that simplifies the analysis of constant-pressure processes, where the heat transferred $Q$ is equal to the change in enthalpy, $\Delta H$. This concept will be vital for understanding thermodynamic cycles and the Second Law of Thermodynamics.