Lecture 11: Heat Engines and the Second Law (Part 1)

0) Orientation and learning outcomes

This lecture builds directly on preceding material from Lectures 7-10, which covered the First Law of Thermodynamics, its sign conventions for internal energy ($U$), heat ($Q$), and work ($W$), and the concepts of reversible and irreversible processes, including $P$ - $V$ work. Previous topics also included adiabatic relations such as $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$ and $TV^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}$, exemplified by the diesel "fire piston" demonstration. Today's focus shifts from simple heat flow to the principles of heat engines, defining their efficiency and the coefficient of performance (CoP). The lecture will construct the ideal Carnot cycle and derive its maximum possible efficiency, ultimately introducing the Second Law of Thermodynamics and the formal definition of entropy ($S$).

By the end of this lecture, students should be able to determine energy changes for each stage of a given heat-engine cycle, calculate the useful work extracted from a cycle using a $P$ - $V$ diagram, recall and state the Kelvin and Clausius forms of the Second Law, and define entropy, explaining its relation $dS = dQ_{rev} / T$.

1) First Law recap and sign conventions

Internal energy ($U$) is a state function, meaning its value depends only on the current state of a system, irrespective of the path taken to reach that state. In contrast, heat ($Q$) and work ($W$) are processes, representing energy transfers that are path-dependent. The First Law of Thermodynamics, a statement of energy conservation, is expressed as $\Delta U = Q + W$. In this convention, $W$ is positive when work is done on the system (e.g., compression), and $Q$ is positive when heat enters the system. This contrasts with the differential form $dQ = dU + PdV$ previously encountered, where $PdV$ represents work done by the gas.

To illustrate, consider internal energy as a bank account balance: $Q$ and $W$ are the deposits or withdrawals that change the balance $\Delta U$. Heat refers to energy transfer driven by temperature differences, involving the chaotic motion of particles. Work, conversely, refers to energy transfer through the ordered motion of particles, such as the force exerted by a piston on a gas.

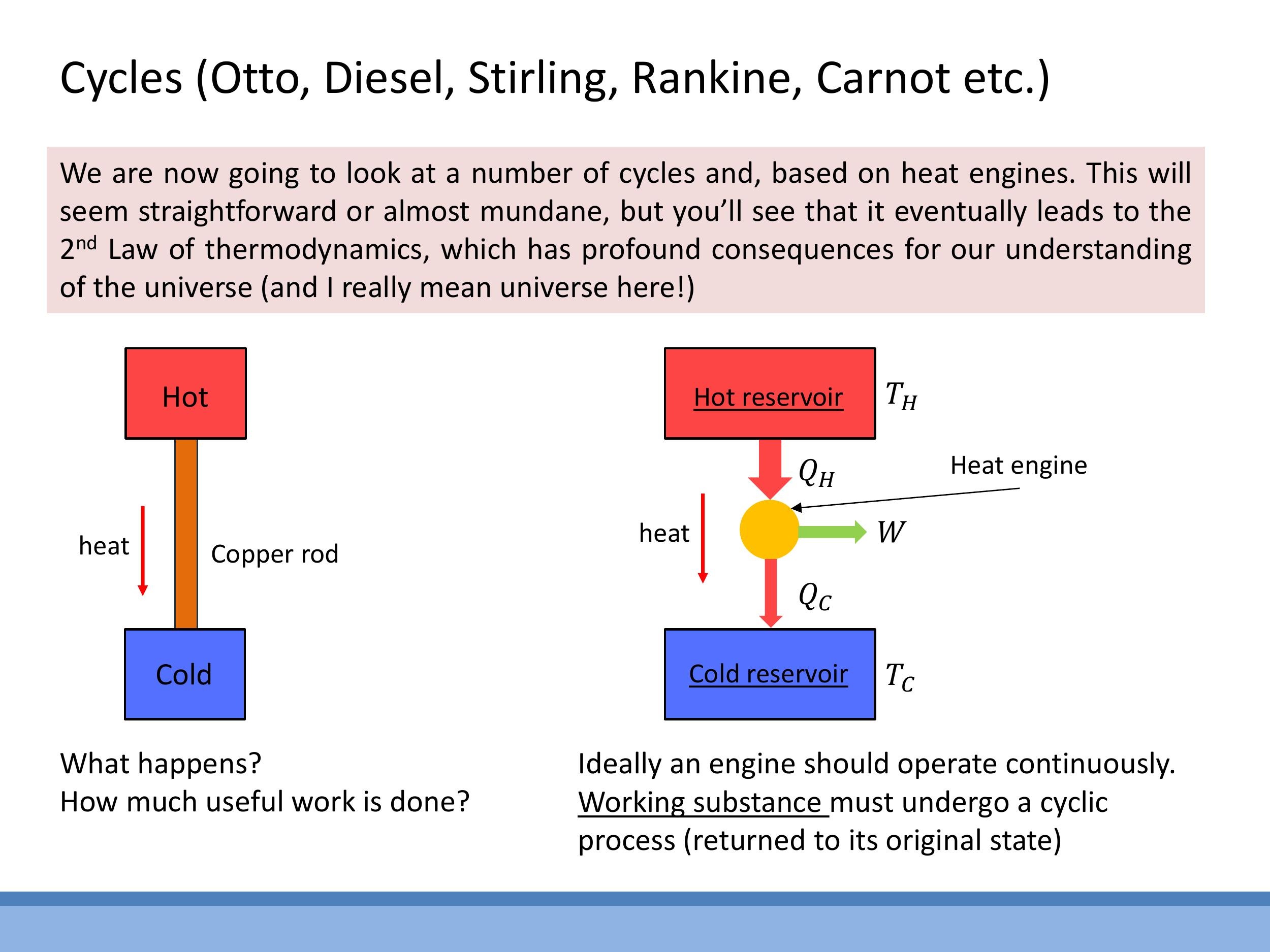

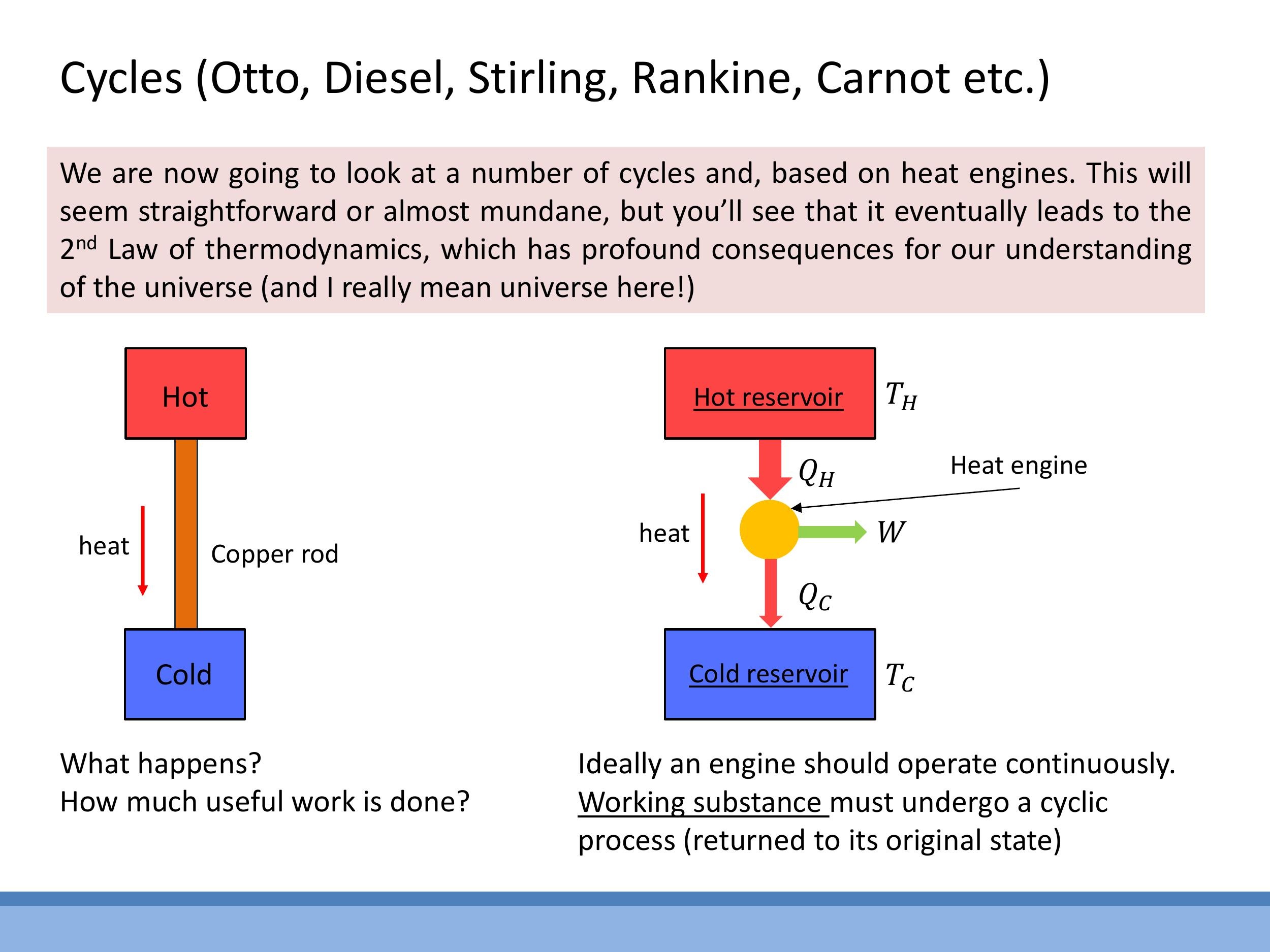

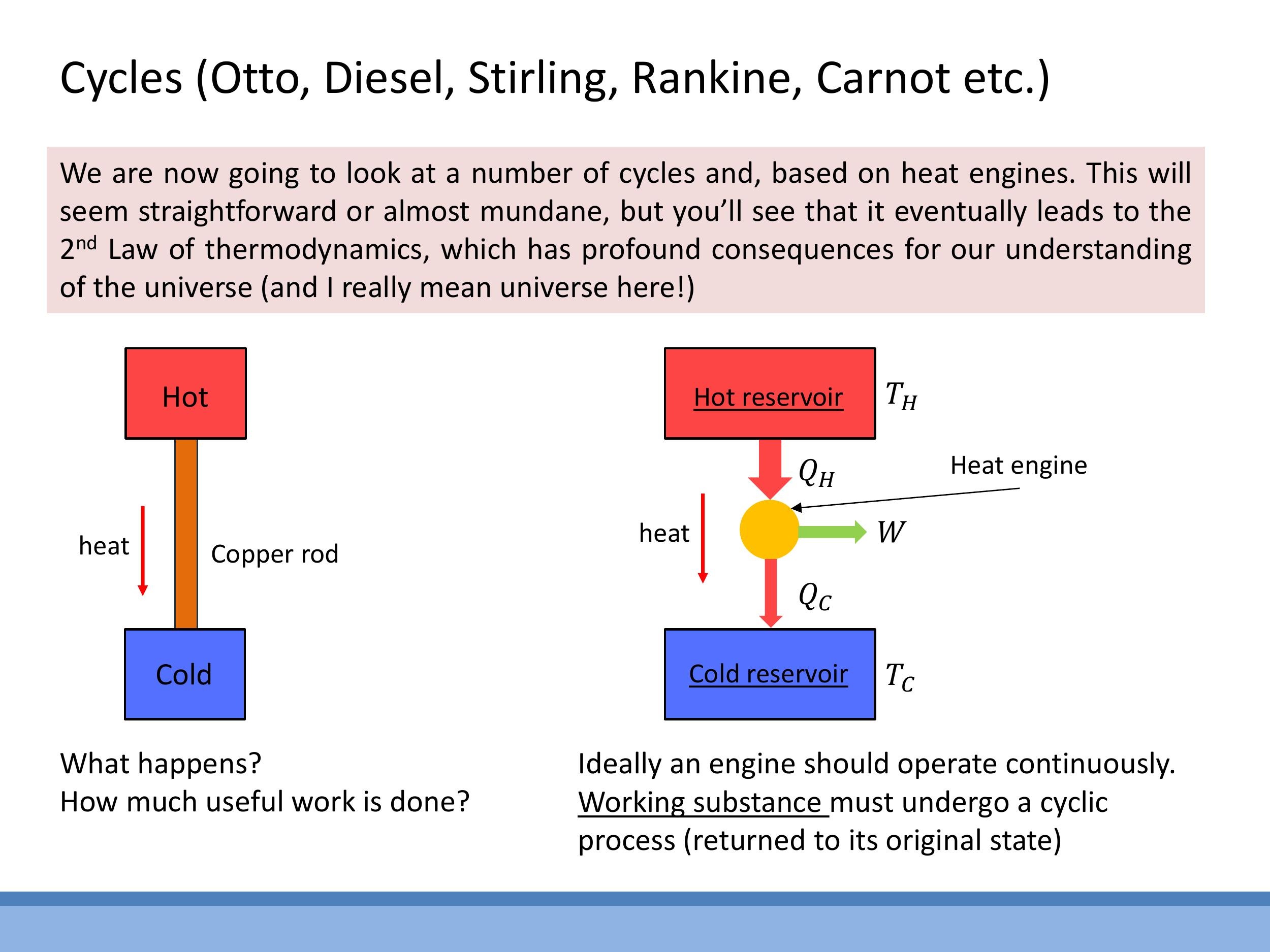

2) From “useless” heat flow to a heat engine

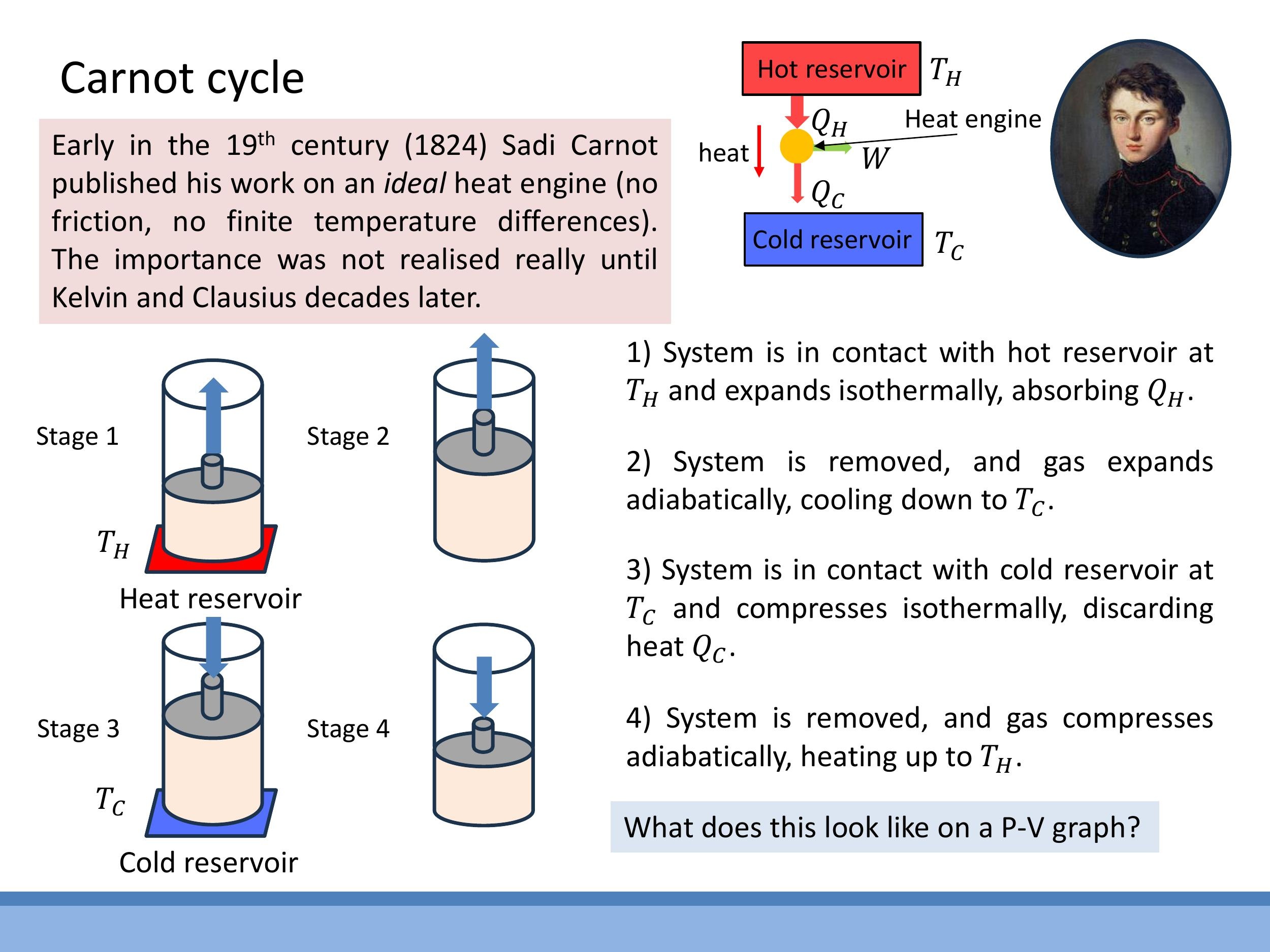

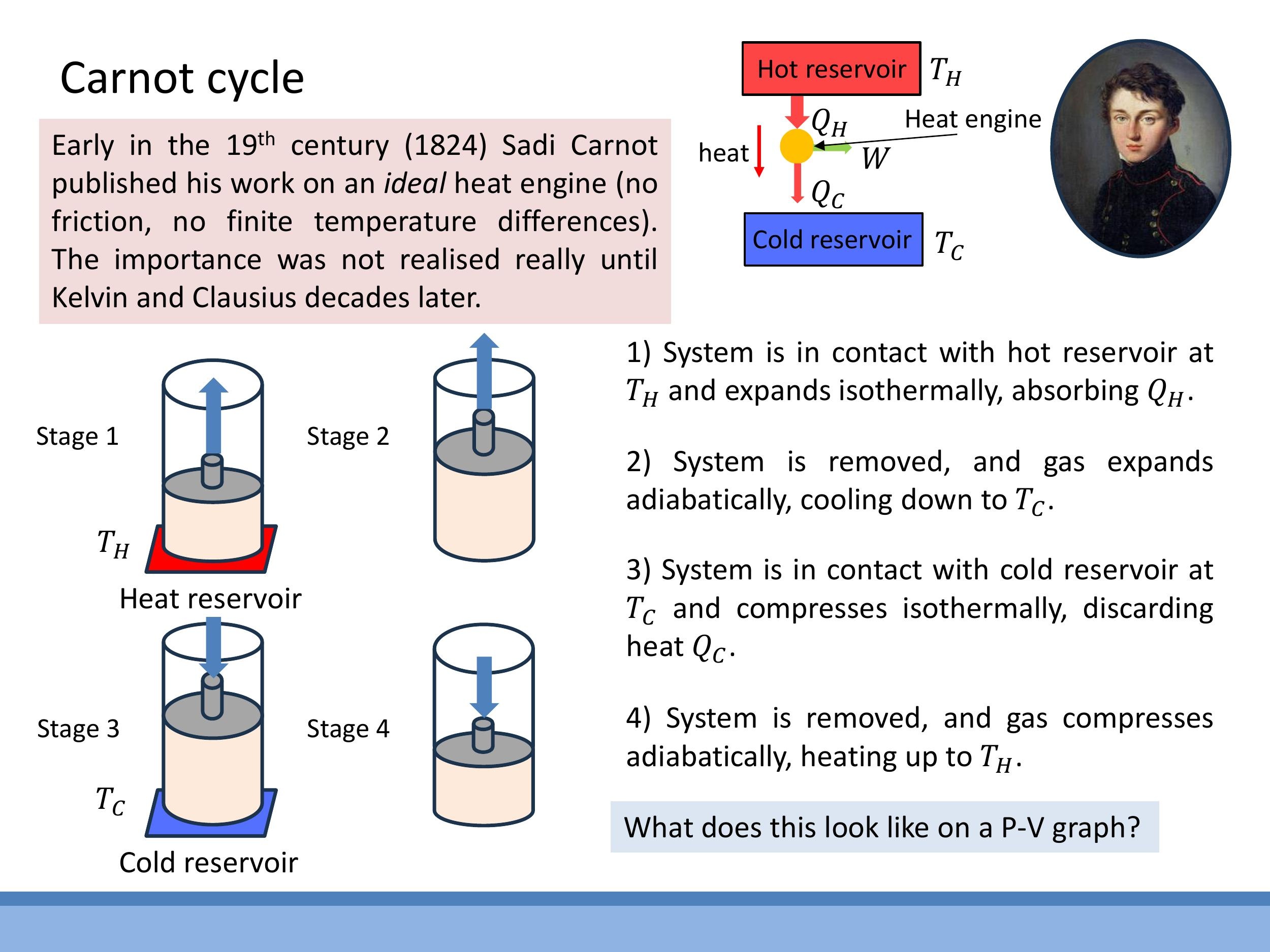

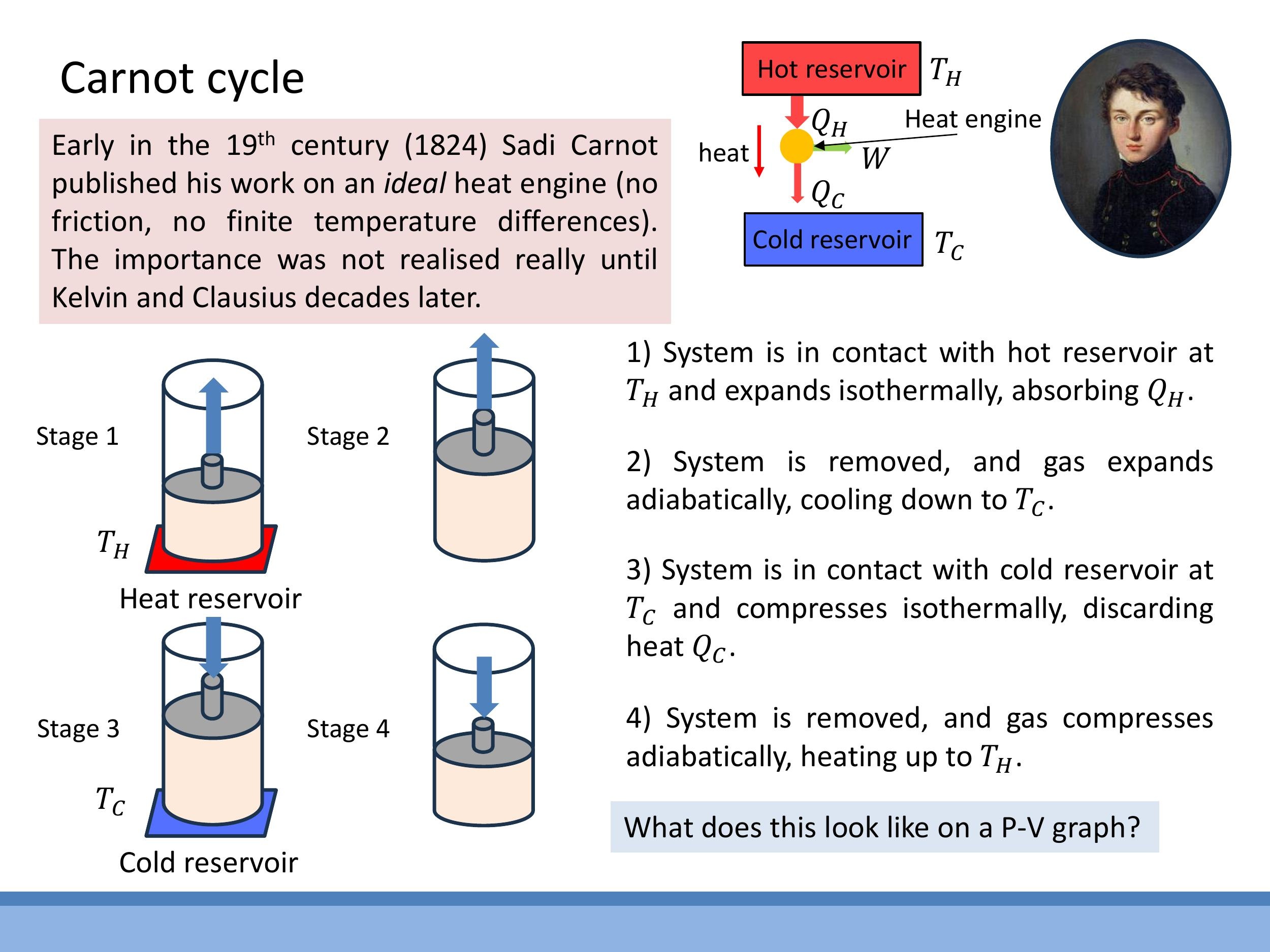

Consider a hot object connected to a cold object by a copper rod. Heat will spontaneously flow from the hot object to the cold object due to the temperature difference. However, this process yields no useful work. A heat engine, in contrast, is designed to operate between a hot reservoir at temperature $T_H$ and a cold reservoir at temperature $T_C$, extracting useful work ($W$) from the heat flow.

The operational principle of a heat engine requires a working substance (e.g., a gas or fluid) to undergo a cyclic process, returning to its initial state after each cycle. In doing so, the engine absorbs heat ($Q_H$) from the hot reservoir, converts a portion of it into useful work ($W$), and rejects the remaining heat ($Q_C$) to the cold reservoir. The energy balance for a complete cycle dictates that the useful work extracted is the difference between the heat absorbed and the heat rejected: $W = Q_H - Q_C$.

3) Efficiency of a heat engine

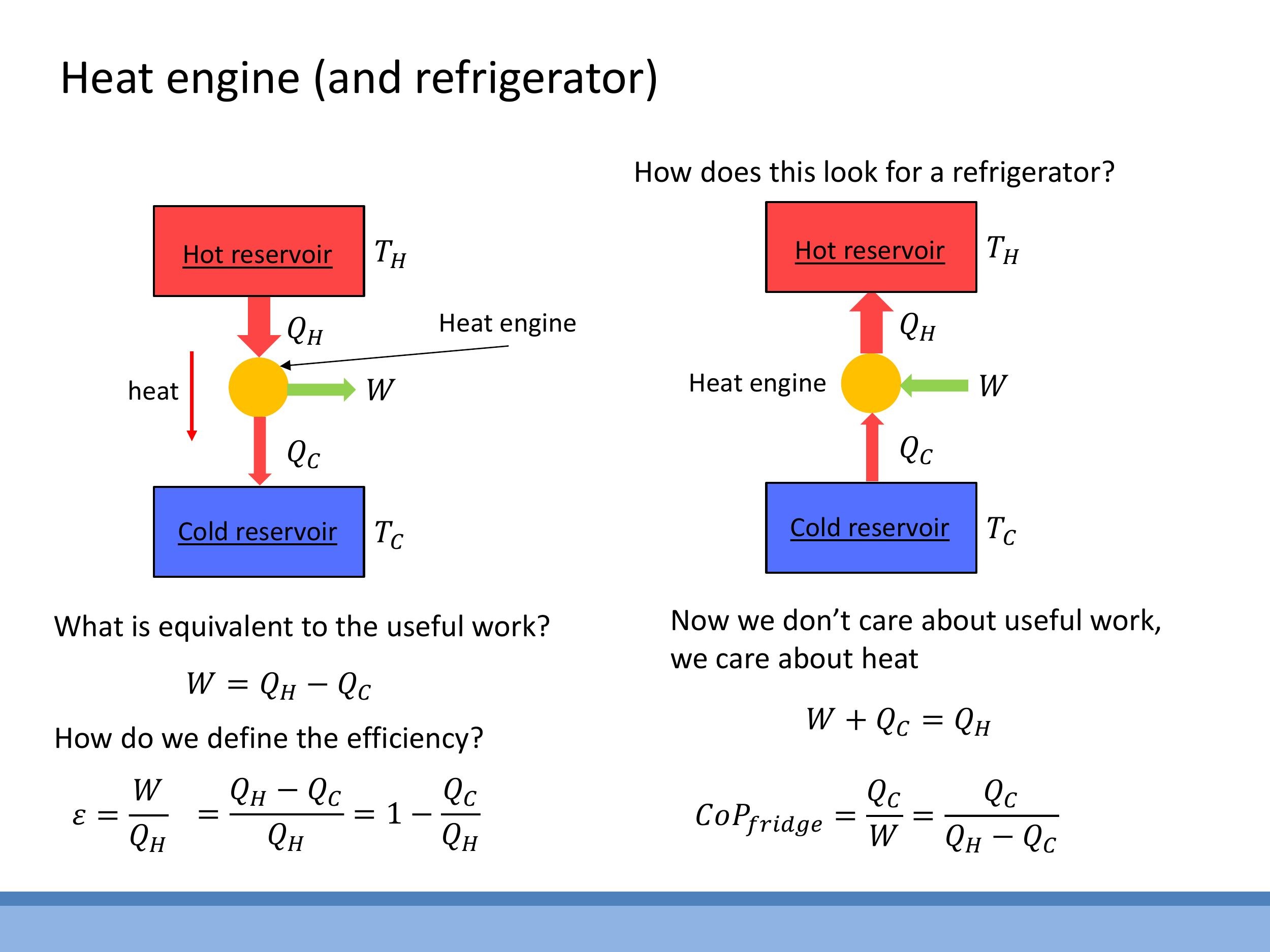

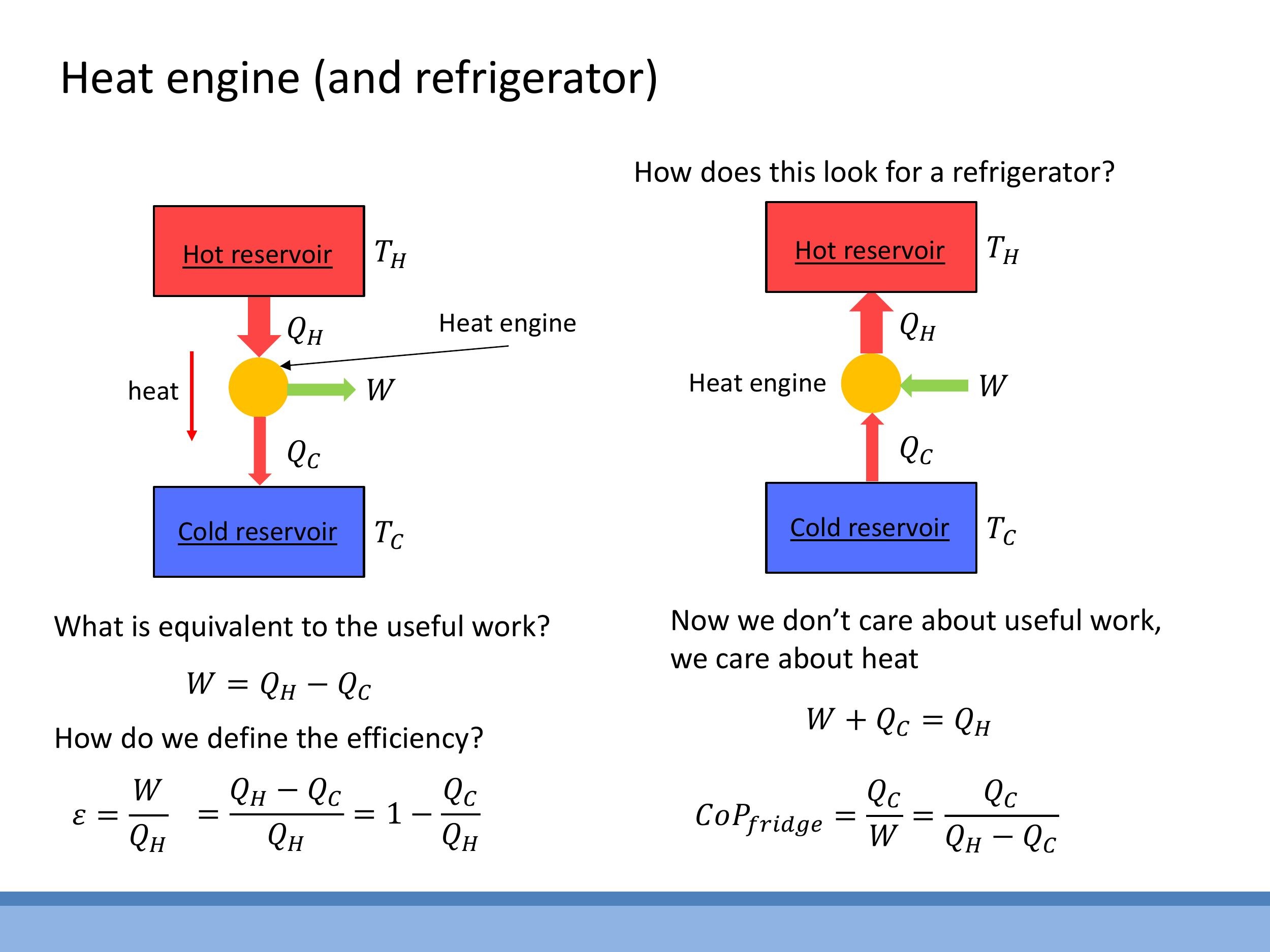

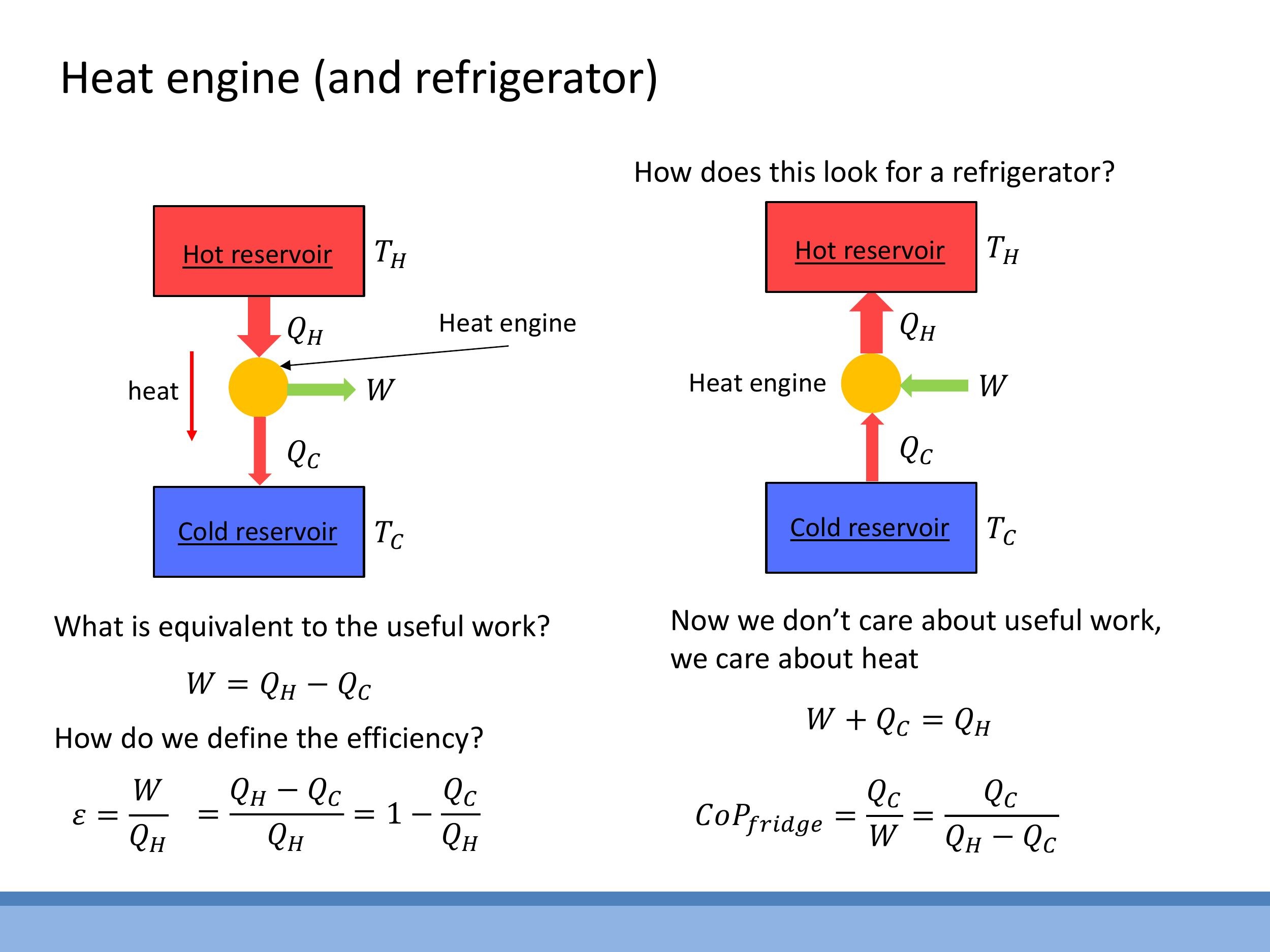

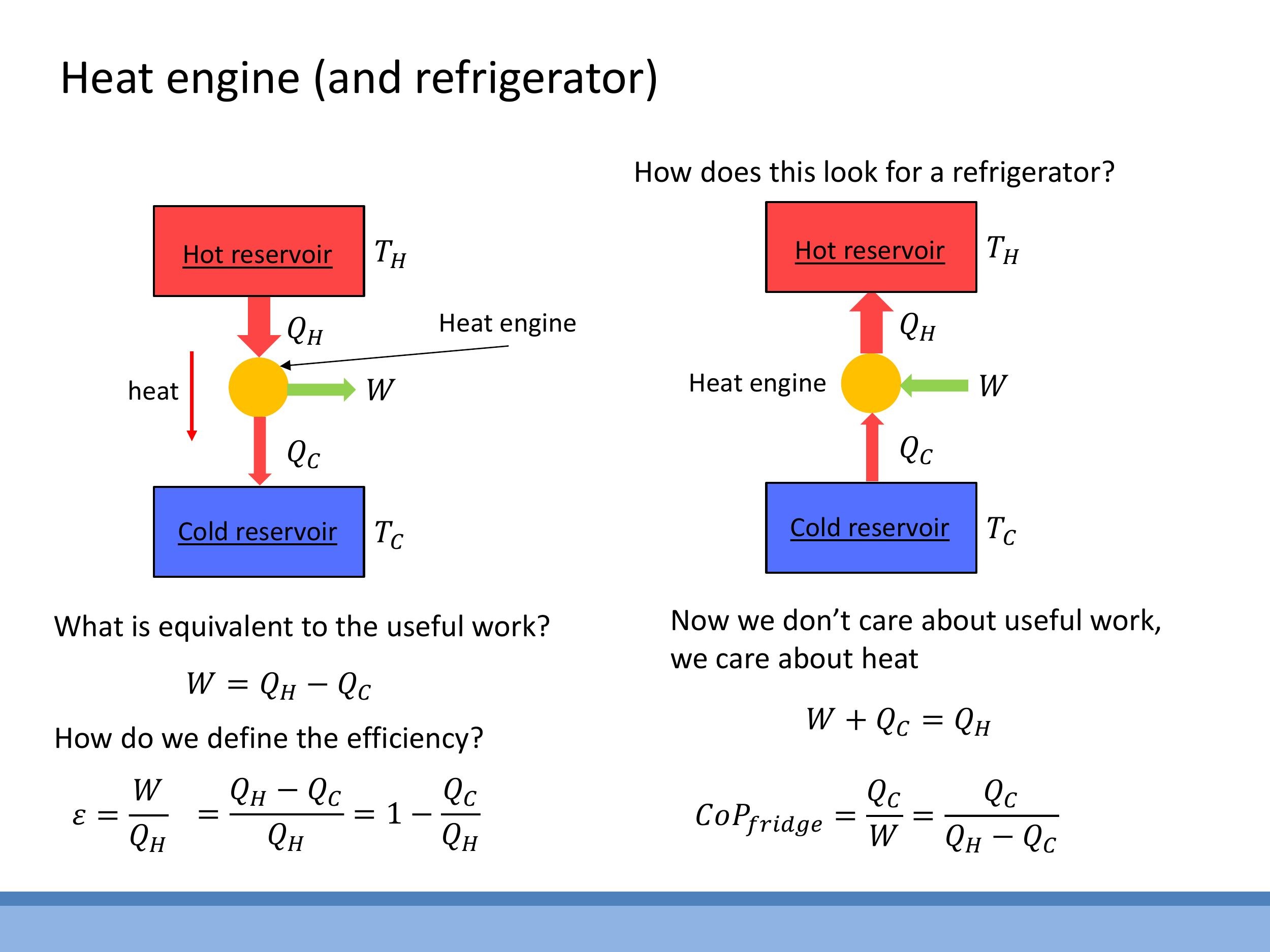

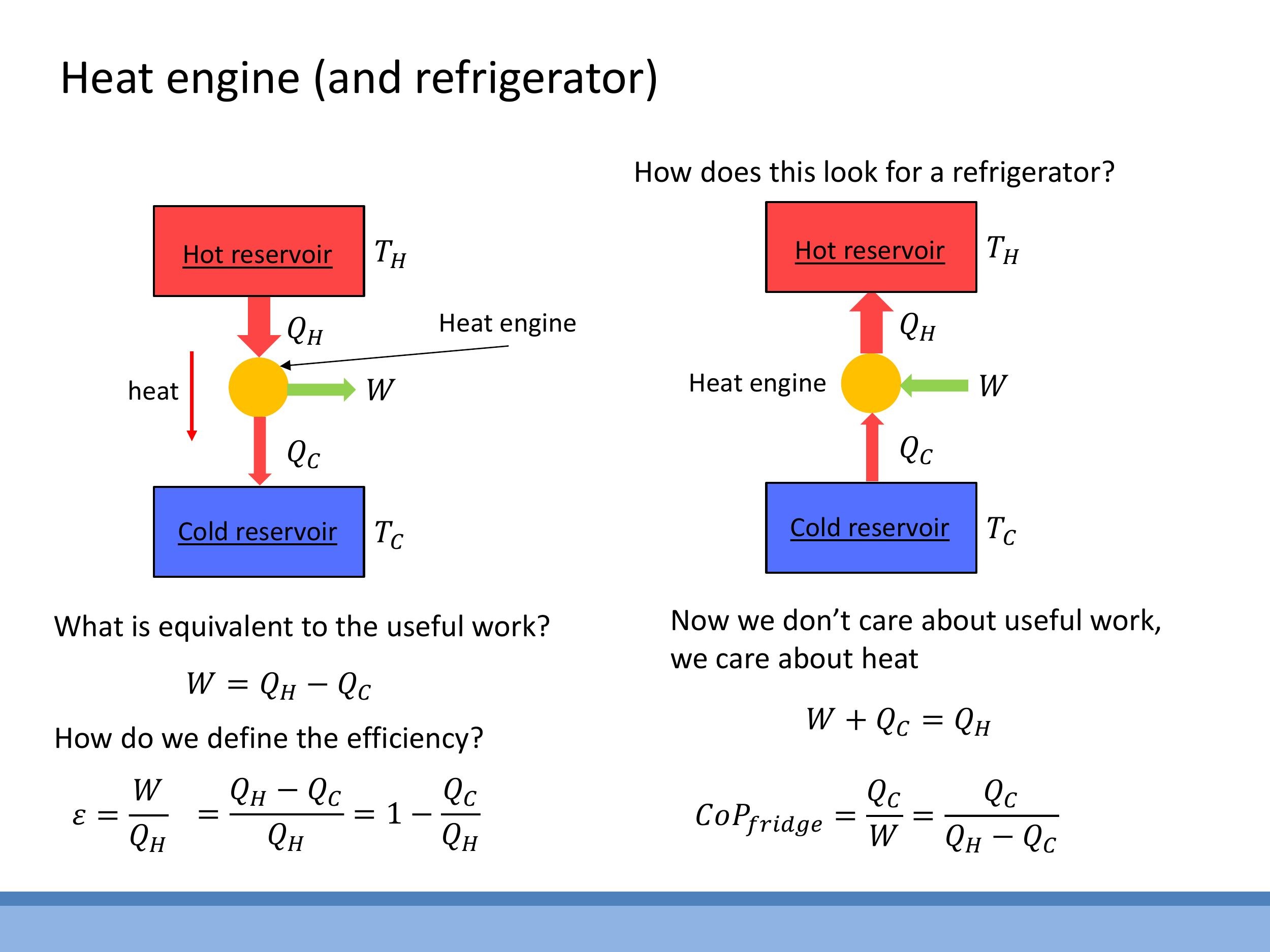

The efficiency ($\varepsilon$) of a heat engine quantifies how effectively it converts absorbed heat into useful work. It is defined as the ratio of the useful work output ($W$) to the total heat absorbed from the hot reservoir ($Q_H$).

This definition can be expanded using the energy balance $W = Q_H - Q_C$:

$$

\varepsilon = \frac{W}{Q_H} = \frac{Q_H - Q_C}{Q_H} = 1 - \frac{Q_C}{Q_H}

$$

This formula demonstrates that the efficiency of any heat engine must always be less than 1 (or 100%). A fraction of the absorbed heat ($Q_C$) must always be rejected to the cold sink to complete the thermodynamic cycle, making perfect conversion of heat to work impossible.

4) Refrigerators and heat pumps (engines run in reverse)

A refrigerator or a heat pump operates as a heat engine in reverse. Instead of producing work from a temperature difference, external work ($W$) is supplied to drive heat "uphill," moving heat ($Q_C$) from a cold reservoir at $T_C$ to a hot reservoir at $T_H$. The total heat rejected to the hot reservoir ($Q_H$) is the sum of the work input and the heat extracted from the cold reservoir: $Q_H = W + Q_C$.

The performance of a refrigerator or heat pump is quantified by its Coefficient of Performance (CoP), rather than efficiency. For a refrigerator, the CoP is defined as the ratio of the heat extracted from the cold reservoir ($Q_C$) to the work input ($W$):

$$

\text{CoP}_{\text{fridge}} = \frac{Q_C}{W} = \frac{Q_C}{Q_H - Q_C}

$$

Unlike engine efficiency, the CoP can be greater than 1. For instance, typical heat pumps often achieve a CoP of 3-5, meaning they can transfer 3 to 5 units of heat energy for every unit of electrical work supplied.

5) The Carnot cycle: the ideal reversible heat engine

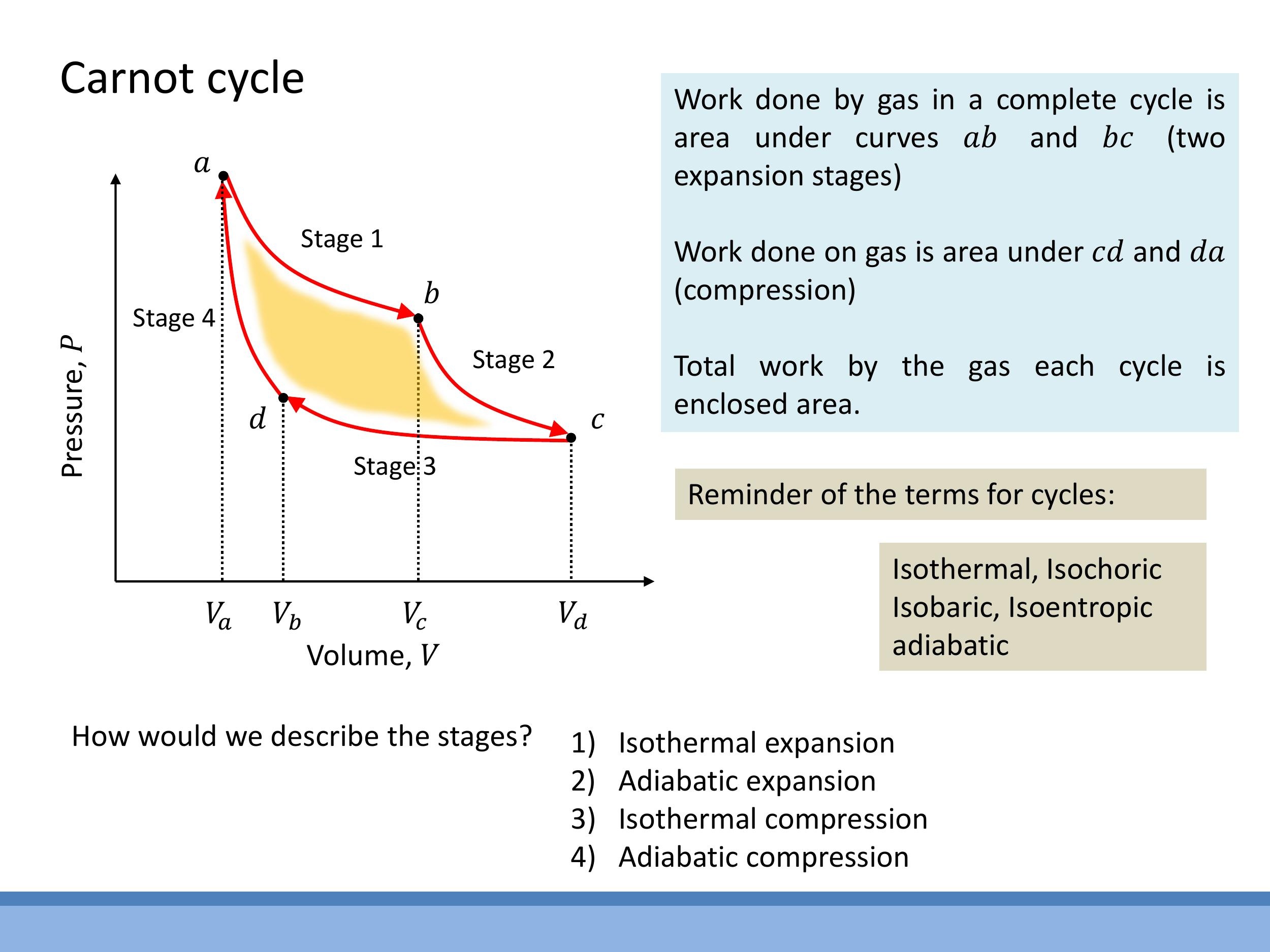

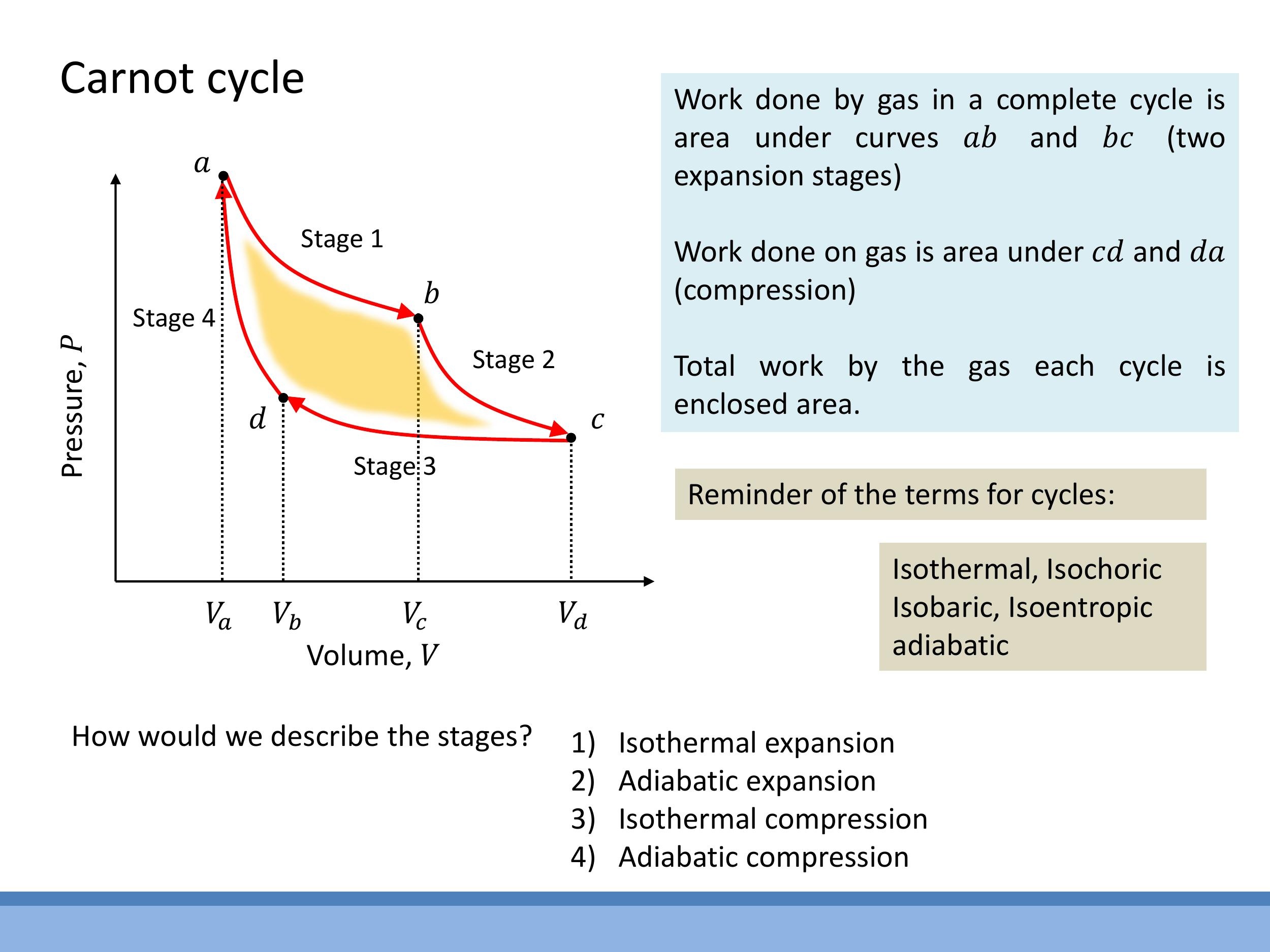

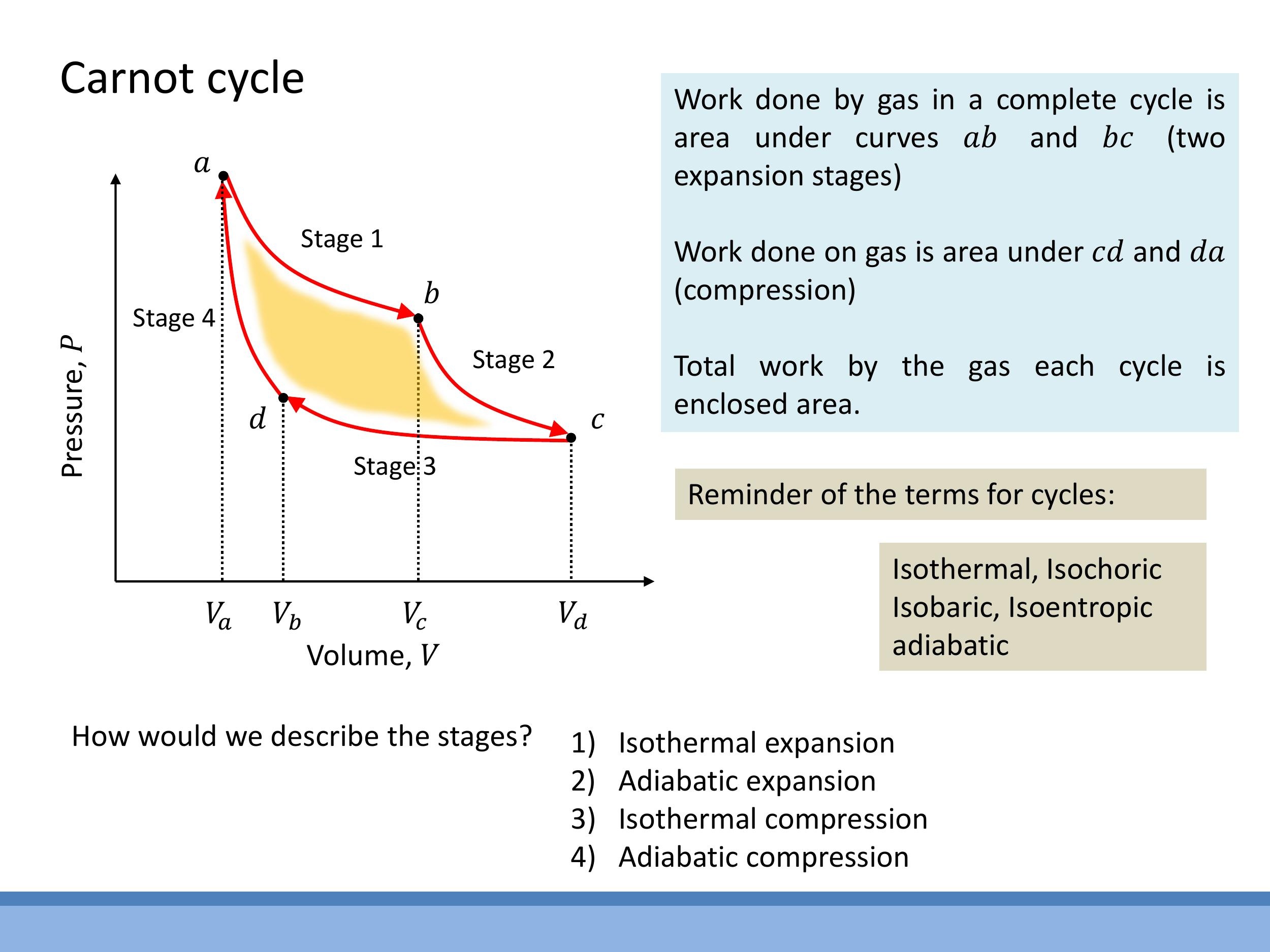

To produce net useful work, a thermodynamic cycle on a $P$ - $V$ diagram must enclose a non-zero area; a simple back-and-forth along a single isotherm would yield no net work. The Carnot cycle, an idealised and perfectly reversible heat engine, achieves this by combining four reversible stages.

The four reversible stages of the Carnot cycle are:

- Isothermal Expansion (a $\to$ b): The working substance expands at a constant high temperature $T_H$, absorbing heat $Q_H$ from the hot reservoir. Since the internal energy of an ideal gas depends only on temperature, $\Delta U = 0$ for this isothermal process, meaning all absorbed heat is converted into work done by the gas.

- Adiabatic Expansion (b $\to$ c): The system is thermally isolated, so no heat is exchanged ($Q = 0$). The gas continues to expand, doing work and consequently cooling from $T_H$ to $T_C$.

- Isothermal Compression (c $\to$ d): The gas is compressed at a constant low temperature $T_C$, rejecting heat $Q_C$ to the cold reservoir.

- Adiabatic Compression (d $\to$ a): The system is again thermally isolated ($Q = 0$). Work is done on the gas, causing its internal energy and temperature to increase, returning it to the initial high temperature $T_H$ and volume $V_a$.

In a $P$ - $V$ diagram, the work done during expansion (stages a $\to$ b and b $\to$ c) is the area under those paths. The work done during compression (stages c $\to$ d and d $\to$ a) is the area under those paths. The net useful work extracted from the cycle is the enclosed area within the loop (the yellow region in the diagram), representing the difference between the work done by the gas and the work done on the gas.

Key thermodynamic terms used to describe processes include:

- Isothermal: Constant temperature ($T$).

- Adiabatic: No heat transfer ($Q = 0$).

- Isochoric: Constant volume ($V$).

- Isobaric: Constant pressure ($P$).

6) Deriving the Carnot efficiency $\varepsilon = 1 - T_C/T_H$

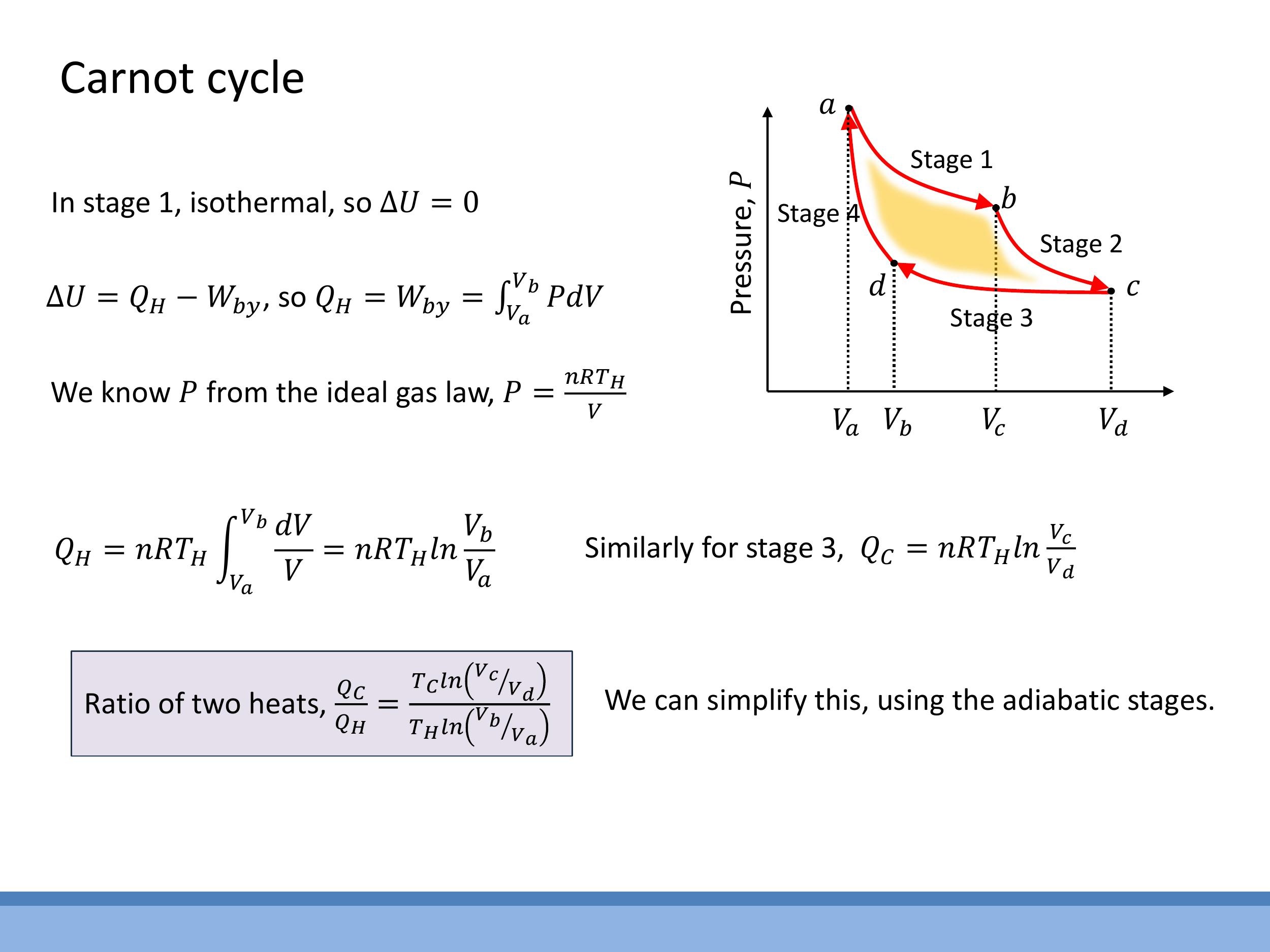

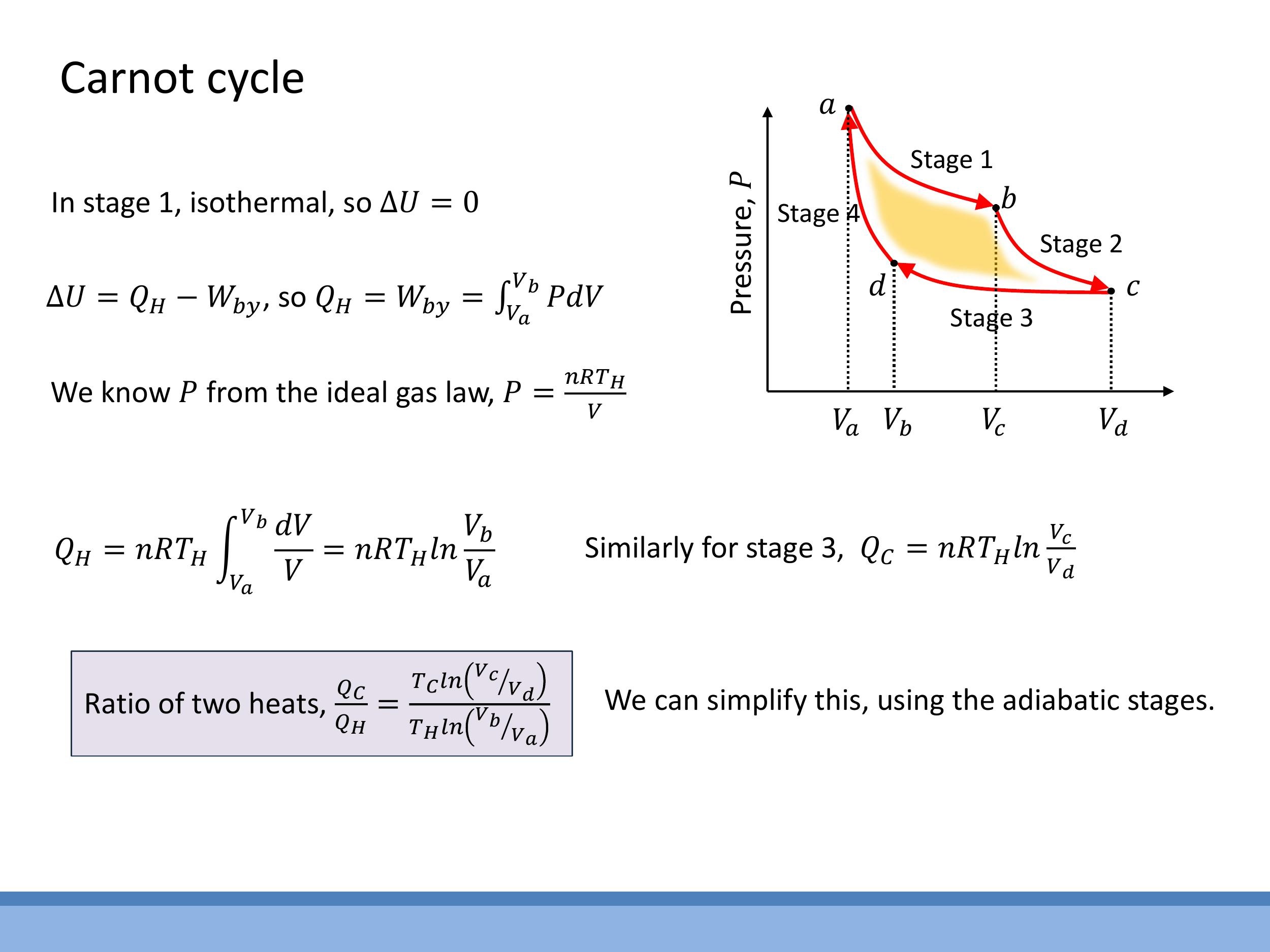

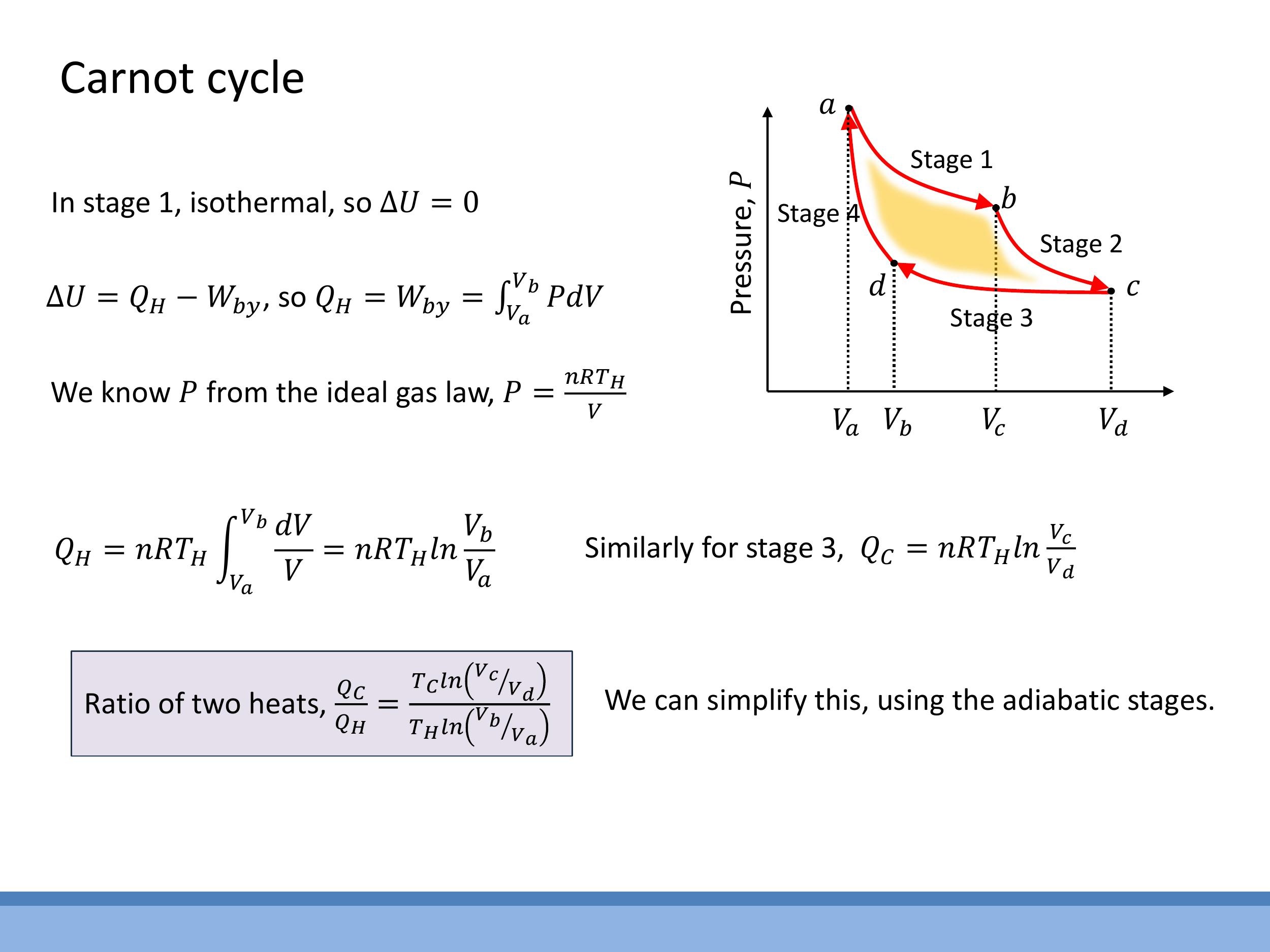

The Carnot efficiency can be derived by considering the heat exchanges during the isothermal stages and the relationships between volumes during the adiabatic stages.

For the isothermal expansion (a $\to$ b) at $T_H$, where $\Delta U = 0$, the heat absorbed $Q_H$ is equal to the work done by the gas:

$$

Q_H = \int_{V_a}^{V_b} P \, dV = n R T_H \ln\left(\frac{V_b}{V_a}\right)

$$

Similarly, for the isothermal compression (c $\to$ d) at $T_C$, the heat rejected $Q_C$ is:

$$

Q_C = n R T_C \ln\left(\frac{V_c}{V_d}\right)

$$

The ratio of these heats is then:

$$

\frac{Q_C}{Q_H} = \frac{T_C \ln(V_c/V_d)}{T_H \ln(V_b/V_a)}

$$

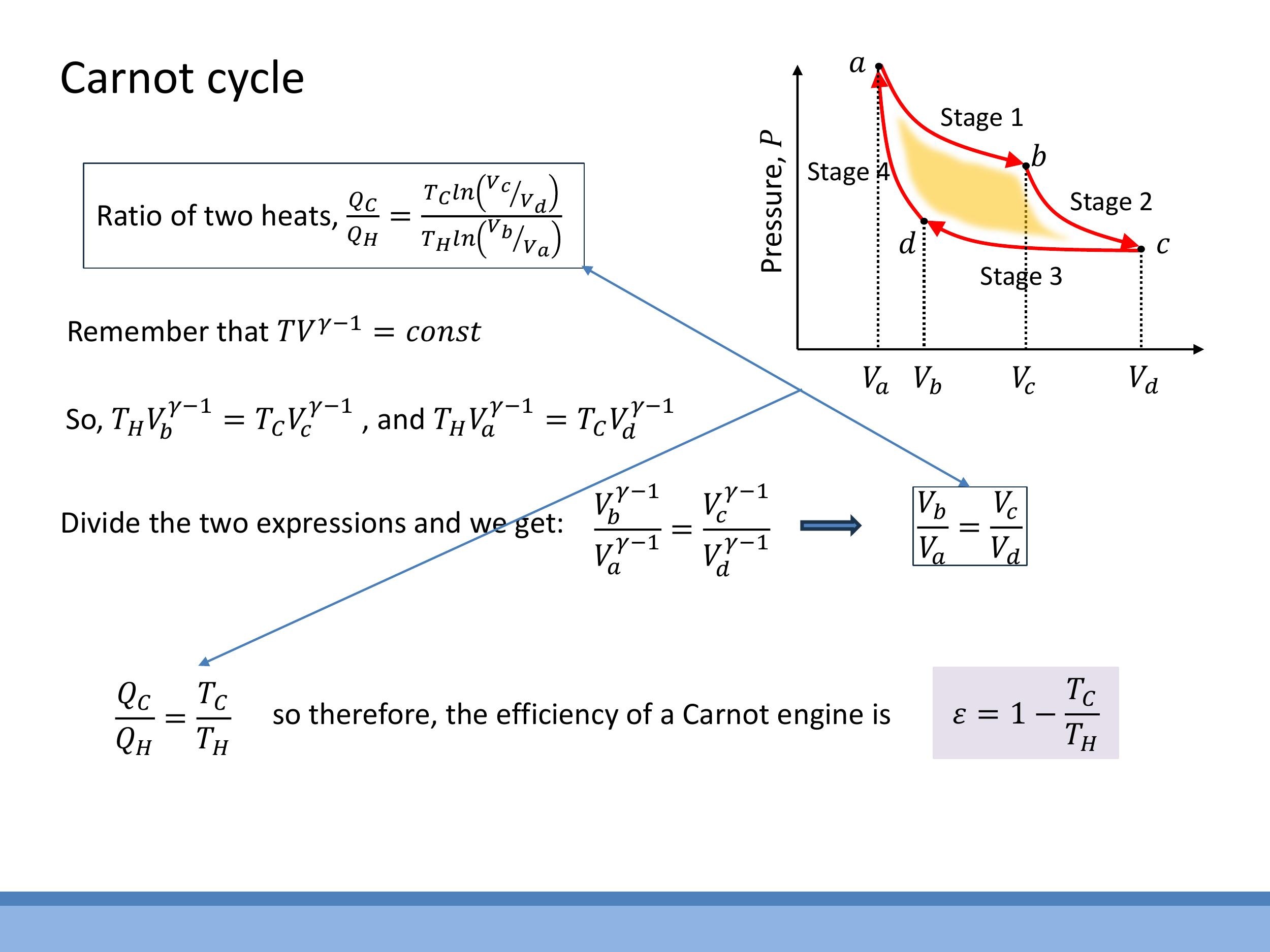

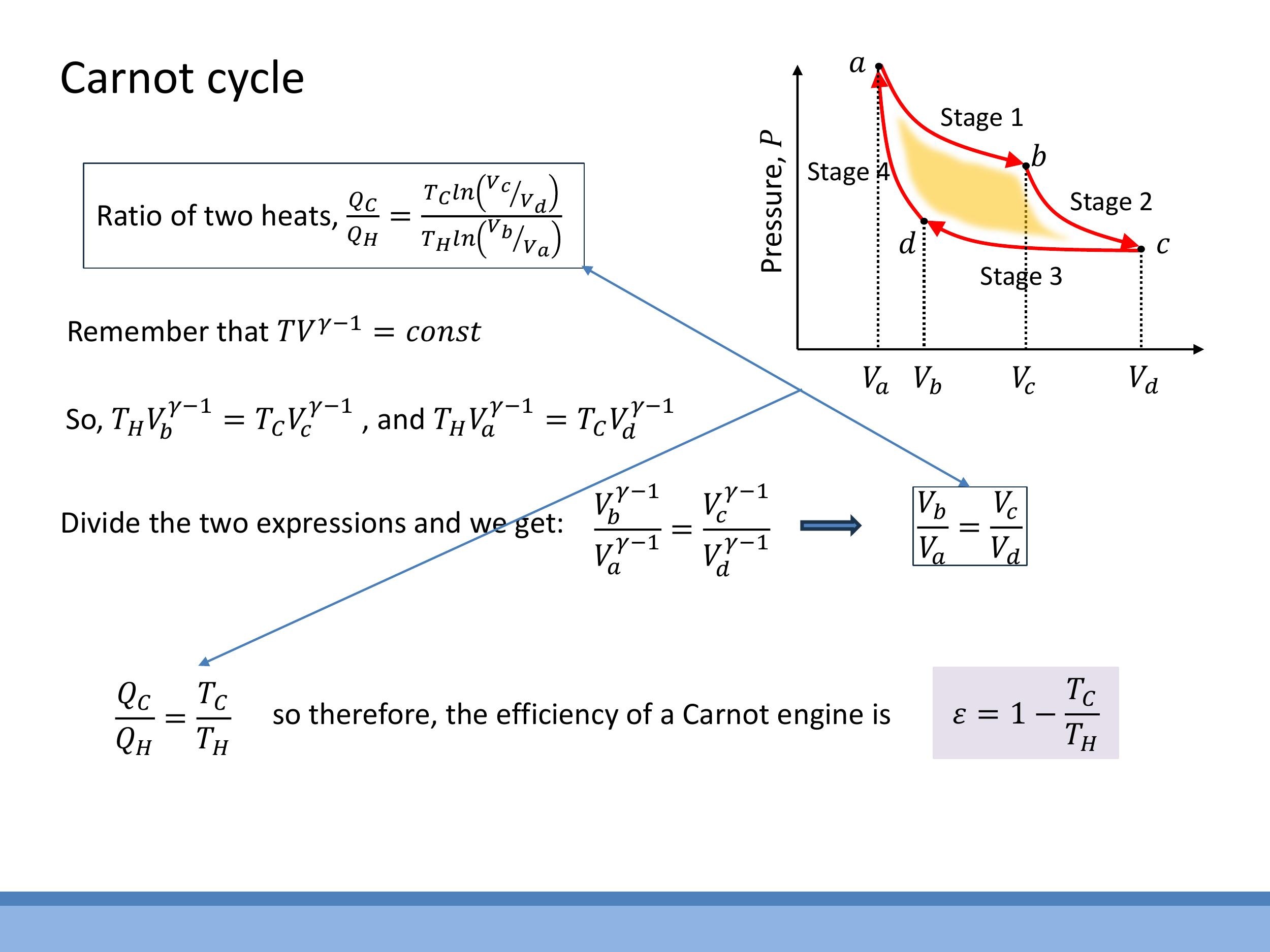

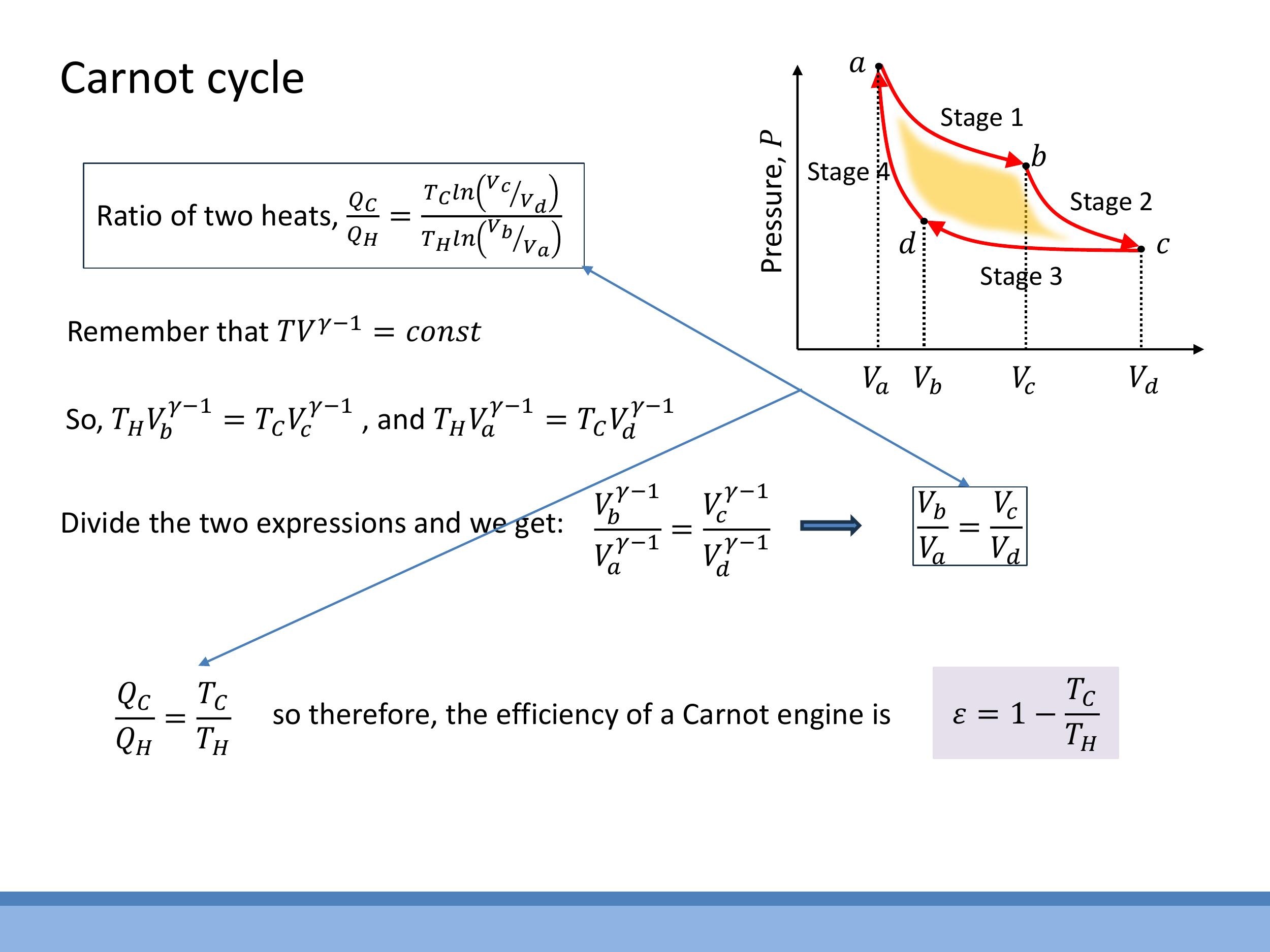

The adiabatic stages (b $\to$ c and d $\to$ a) are governed by the relation $TV^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}$. Applying this to the transitions:

$$

T_H V_b^{\gamma-1} = T_C V_c^{\gamma-1}

$$

$$

T_H V_a^{\gamma-1} = T_C V_d^{\gamma-1}

$$

Dividing these two equations yields:

$$

\left(\frac{V_b}{V_a}\right)^{\gamma-1} = \left(\frac{V_c}{V_d}\right)^{\gamma-1}

$$

This simplifies to the crucial relation $\frac{V_b}{V_a} = \frac{V_c}{V_d}$. Substituting this back into the heat ratio equation, the logarithmic terms cancel:

$$

\frac{Q_C}{Q_H} = \frac{T_C}{T_H}

$$

Finally, substituting this into the definition of efficiency $\varepsilon = 1 - \frac{Q_C}{Q_H}$ gives the Carnot efficiency:

$$

\varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}} = 1 - \frac{T_C}{T_H}

$$

This formula demonstrates that the maximum possible efficiency of a heat engine depends solely on the absolute temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs, and is independent of the working substance or the specific design of the engine.

Side Note: There was a mislabelling of volumes ($V_a, V_b, V_c, V_d$) on the $P$ - $V$ diagrams in the original lecture slides, which will be corrected in the uploaded notes.

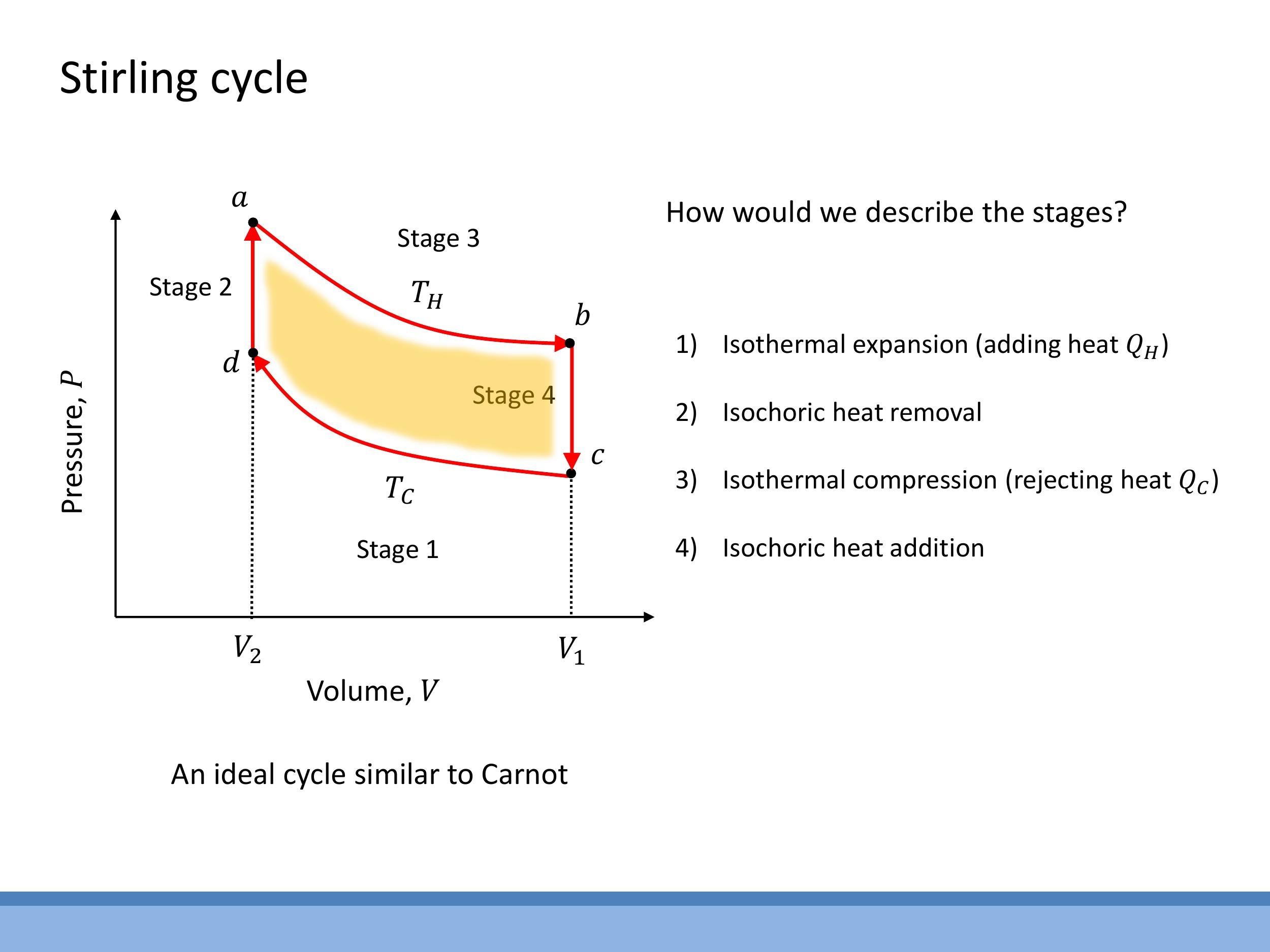

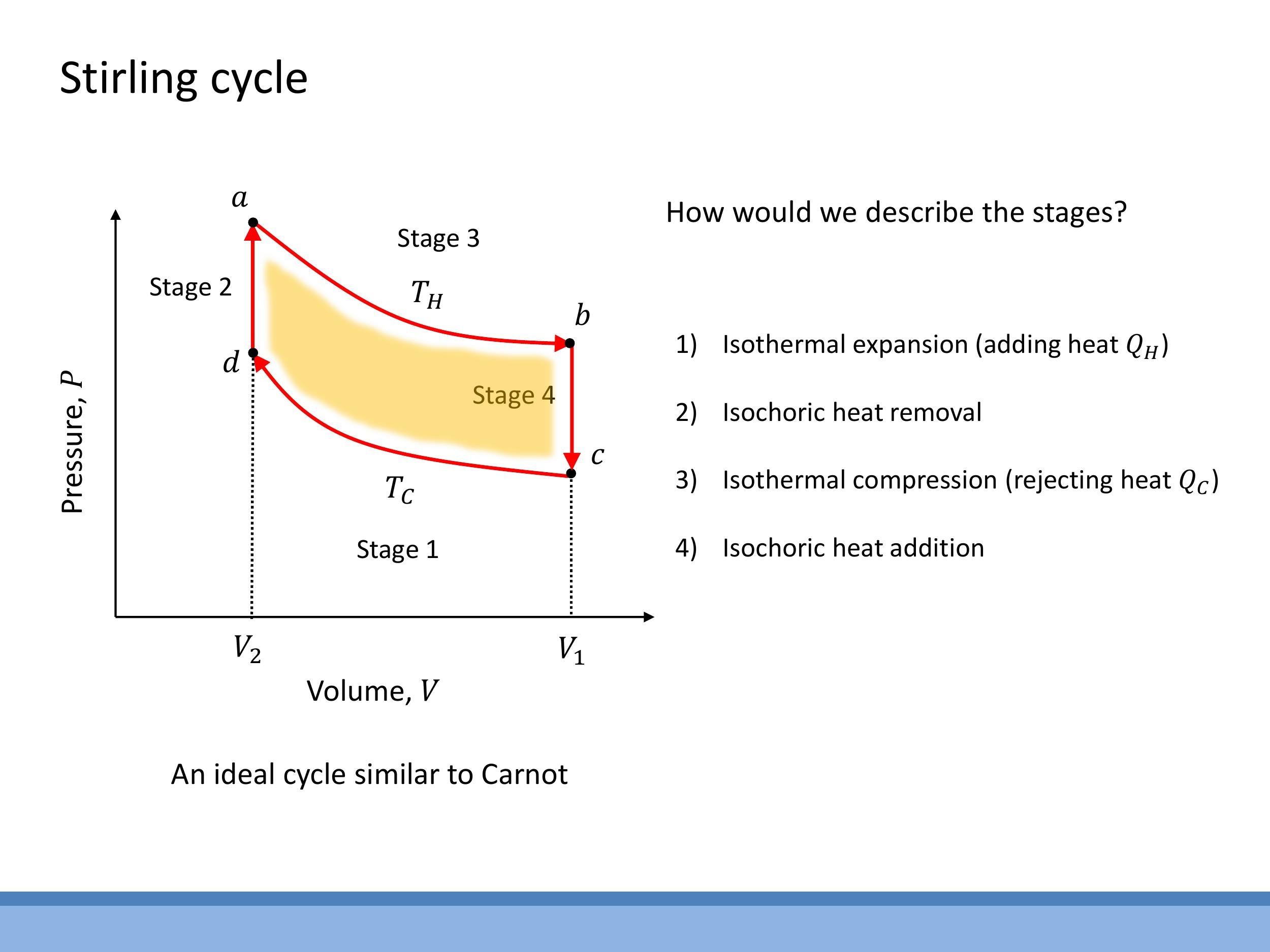

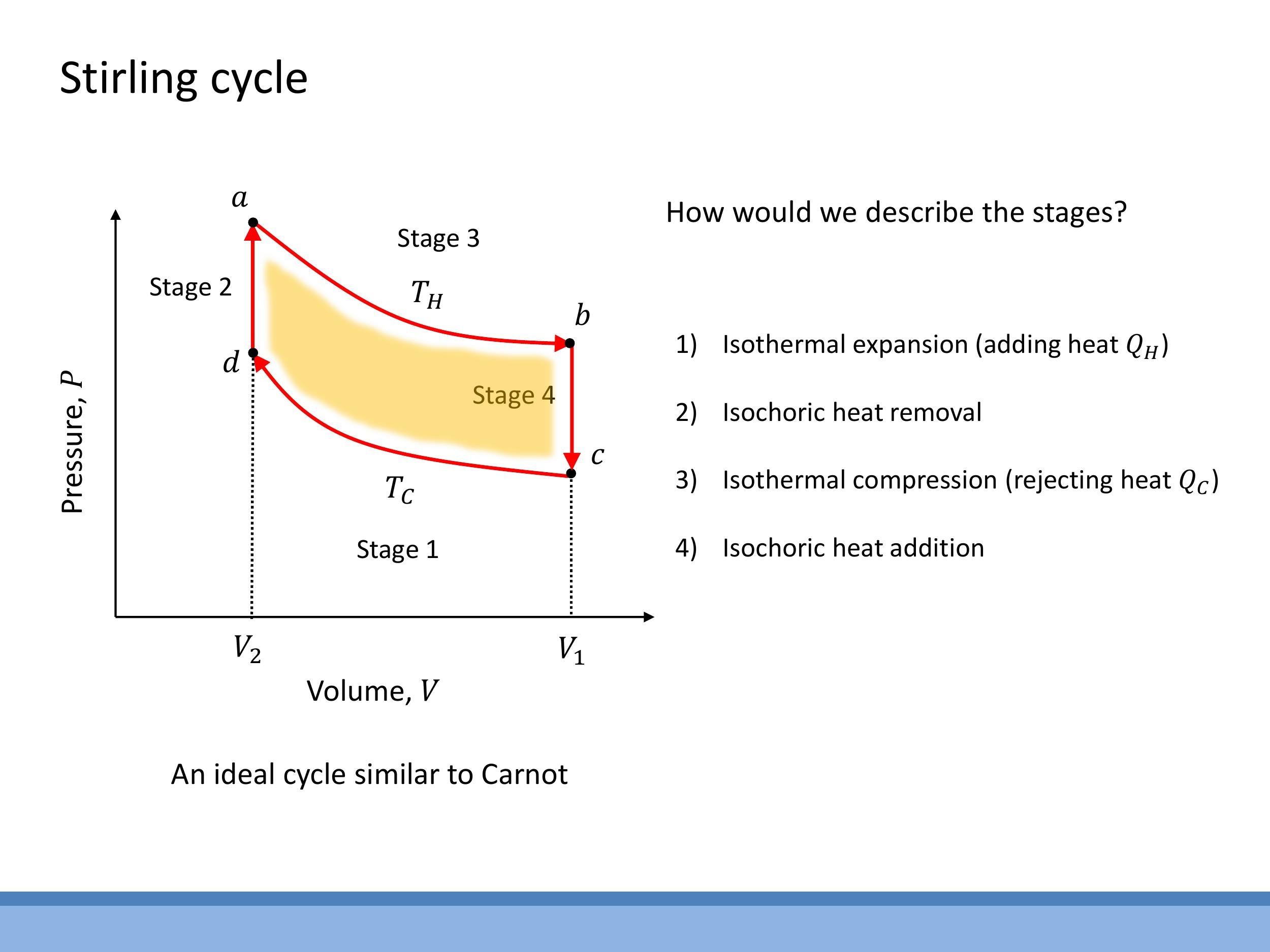

7) The Stirling cycle and live engine demonstration

The Stirling cycle is another ideal reversible heat engine cycle. Its structure on a $P$ - $V$ diagram consists of two isothermal processes (expansion at $T_H$ and compression at $T_C$) connected by two isochoric (constant volume) heat transfer steps. An ideal Stirling engine operating reversibly between the same hot ($T_H$) and cold ($T_C$) reservoirs achieves the same maximum efficiency bound as the Carnot cycle: $\varepsilon = 1 - T_C/T_H$.

A live demonstration with Stirling engines visually illustrates this principle. When an engine was placed on hot water (approaching $100 \, \text{°C} $ for $ T_H $, with the top plate at room temperature $ T_C \approx 20 \, \text{°C} $), it accelerated rapidly. This is due to the large temperature difference ($ \Delta T \approx 80 \, \text{K} $), leading to a higher efficiency. In contrast, when another engine was placed on ice water ($ T_C = 0 \, \text{°C} $, with the top plate at room temperature $ T_H \approx 20 \, \text{°C} $), it ran much more slowly or struggled to operate. The smaller temperature difference ($ \Delta T \approx 20 \, \text{K}$) in this case resulted in poorer performance. This speed difference directly reflects the dependence of efficiency on the temperature difference between the hot and cold reservoirs, demonstrating that a larger temperature difference yields greater available work per cycle.

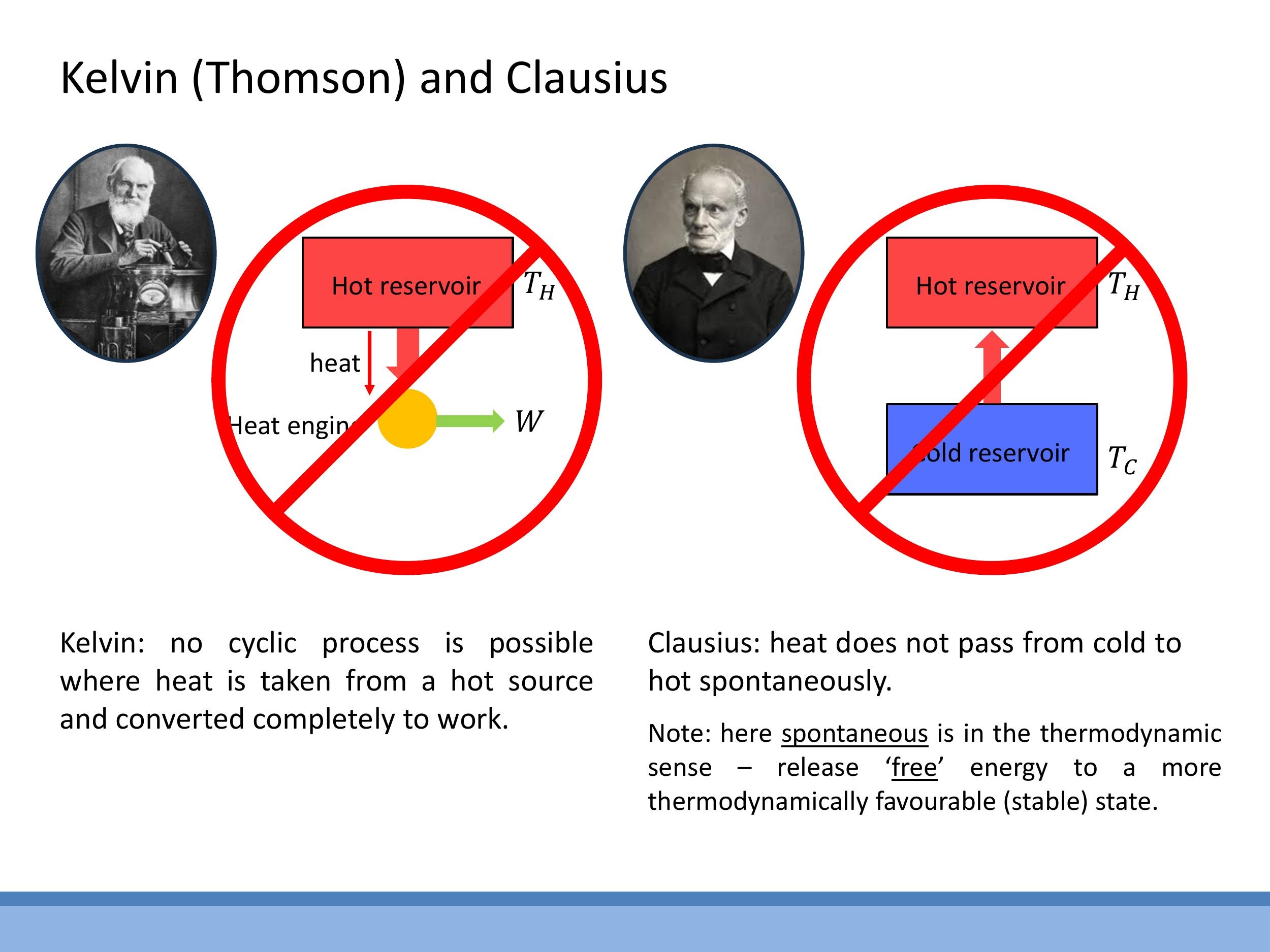

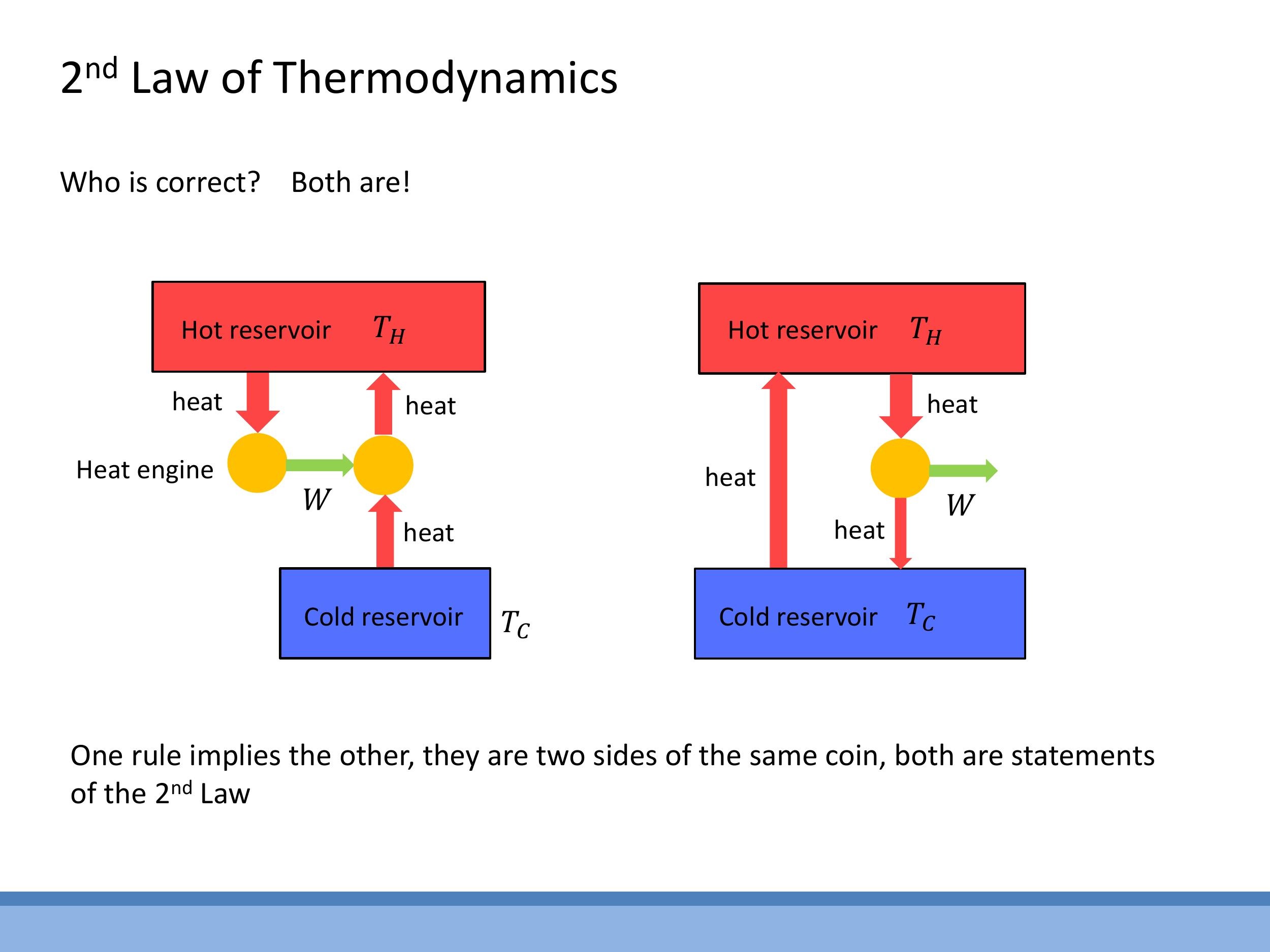

8) The Second Law: Kelvin and Clausius statements and equivalence

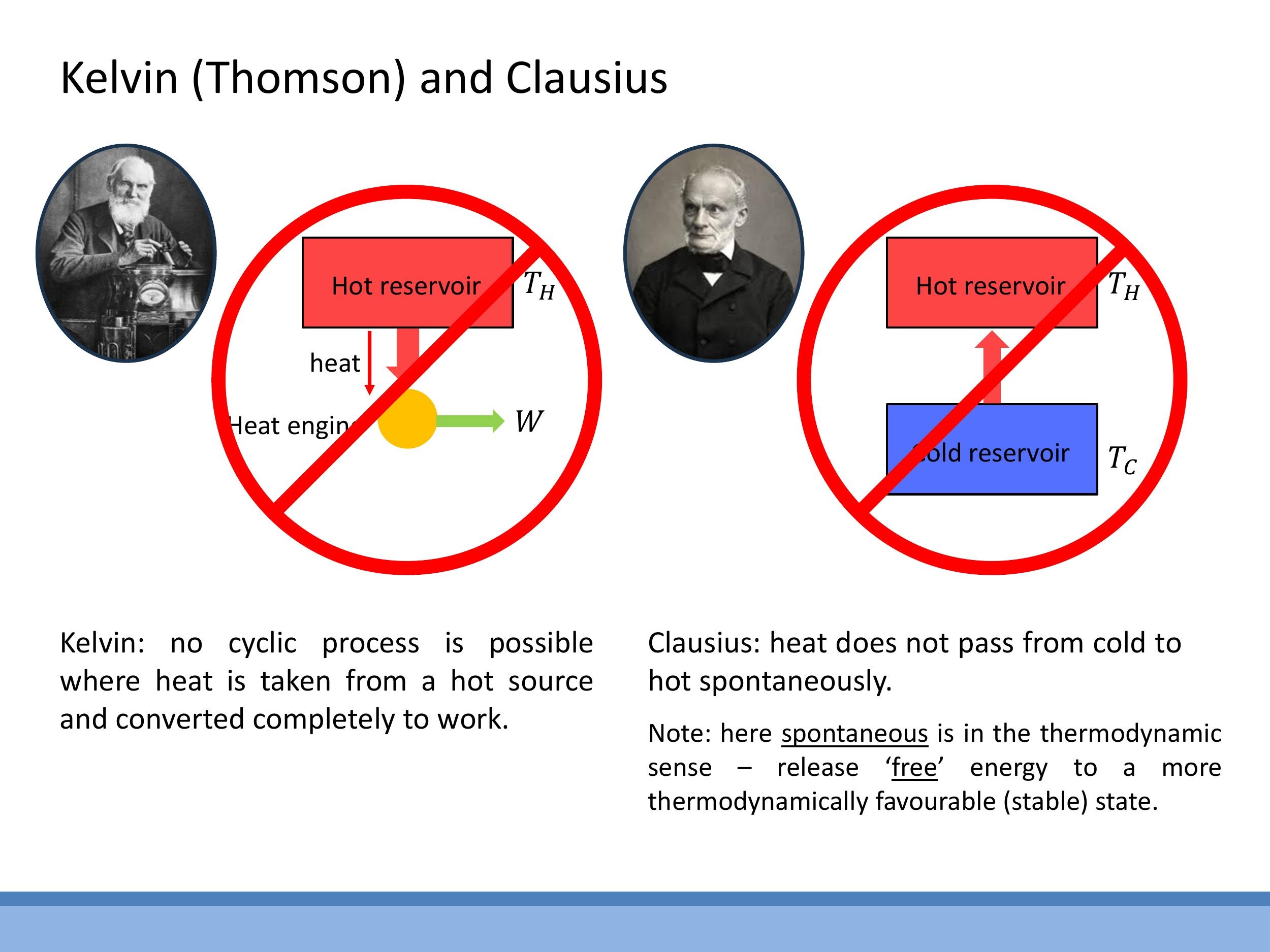

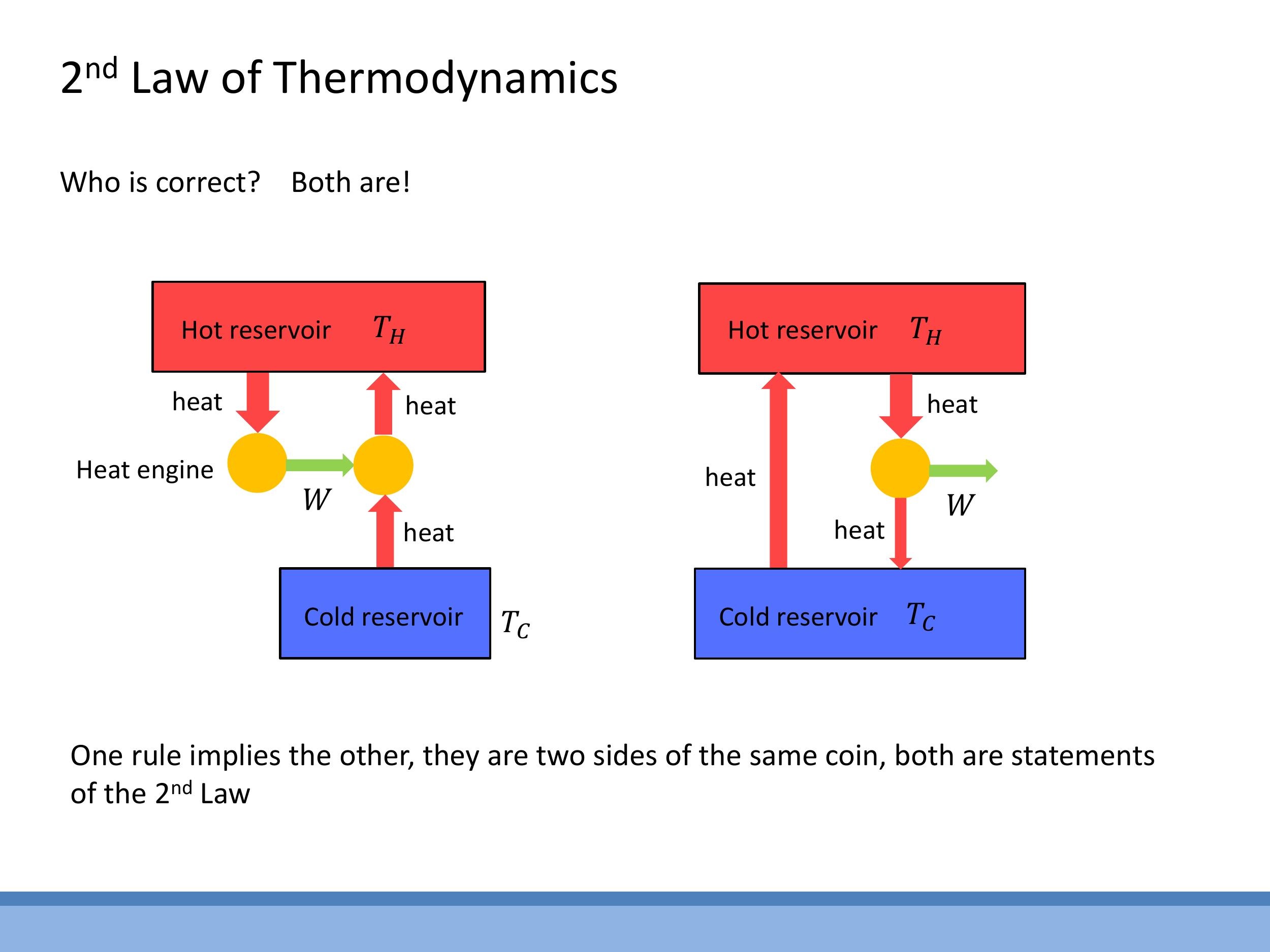

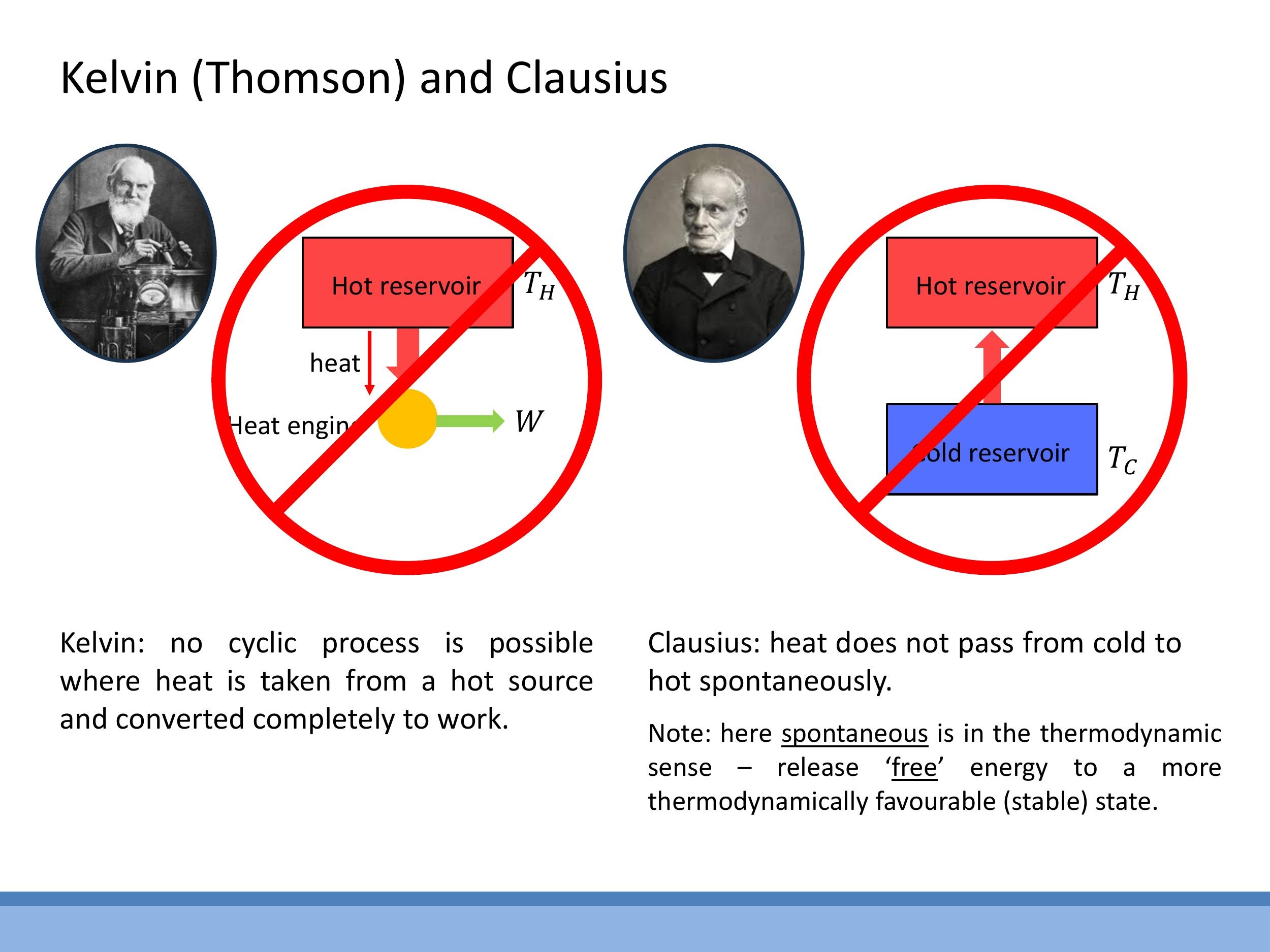

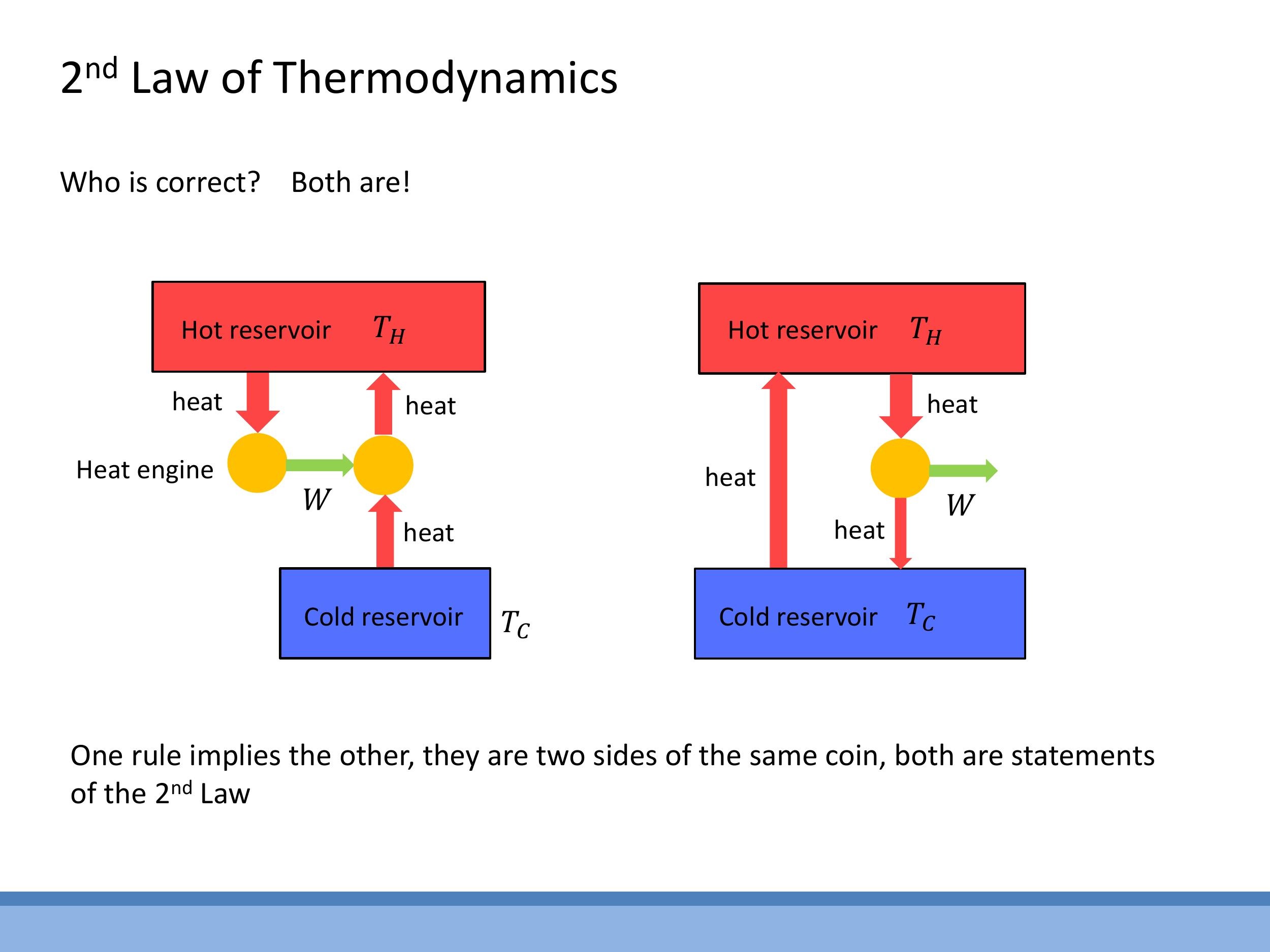

The Second Law of Thermodynamics establishes the direction of spontaneous processes and places fundamental limits on the efficiency of heat engines. It can be stated in two equivalent forms:

The Clausius statement asserts that heat does not pass spontaneously from a cold body to a hot body. The term "spontaneous" here refers to the thermodynamic tendency towards a more favourable, higher entropy state, not necessarily an instantaneous process.

The Kelvin (Thomson) statement declares that no cyclic process is possible that takes heat from a single hot source and converts it completely into work. This implies the necessity of a cold sink; some energy must always be rejected to a cold reservoir to complete a cycle and extract useful work.

These two statements are equivalent, meaning that if one were false, it would be possible to construct a device that violates the other. They represent two complementary aspects of the same fundamental physical law.

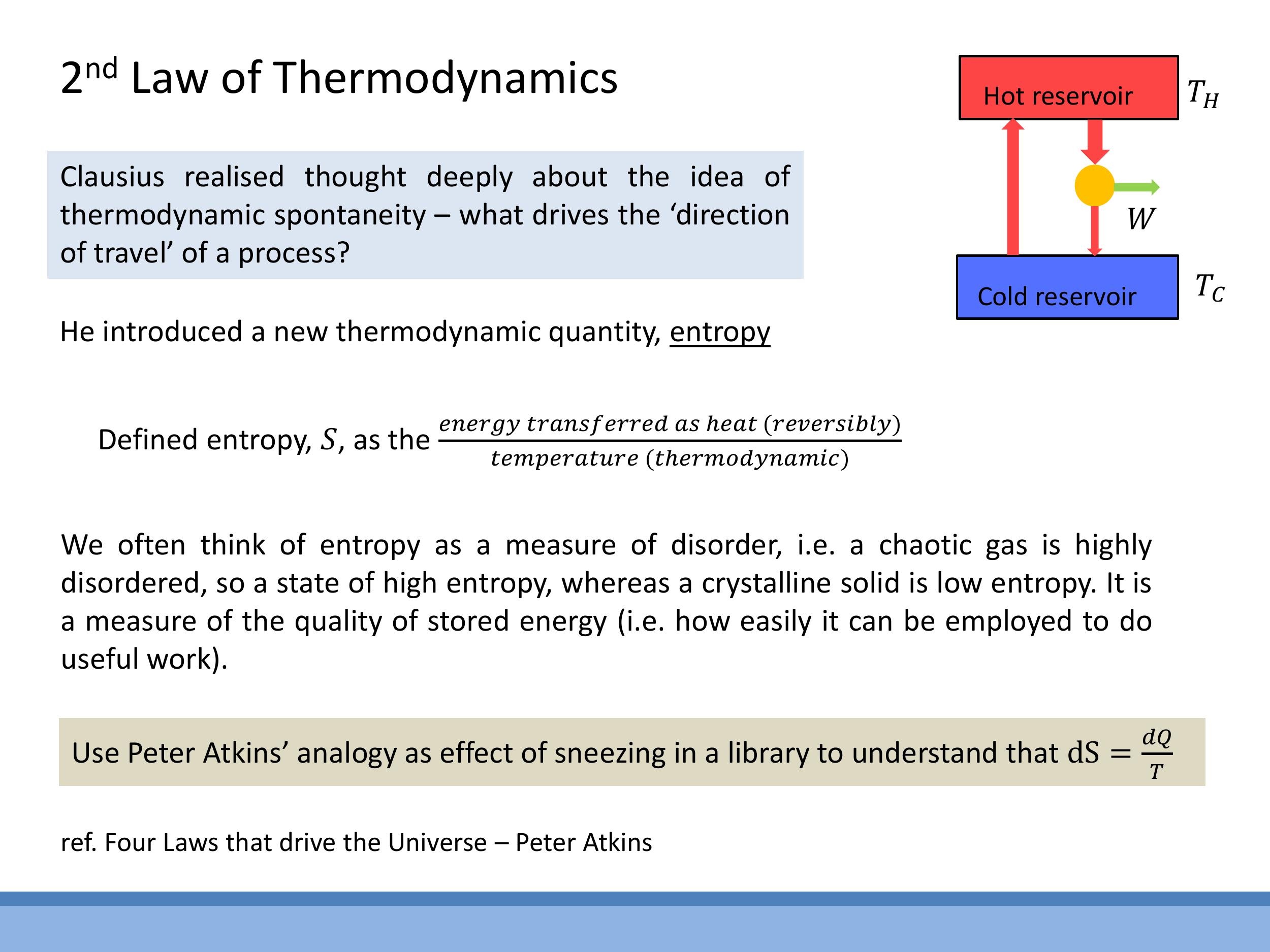

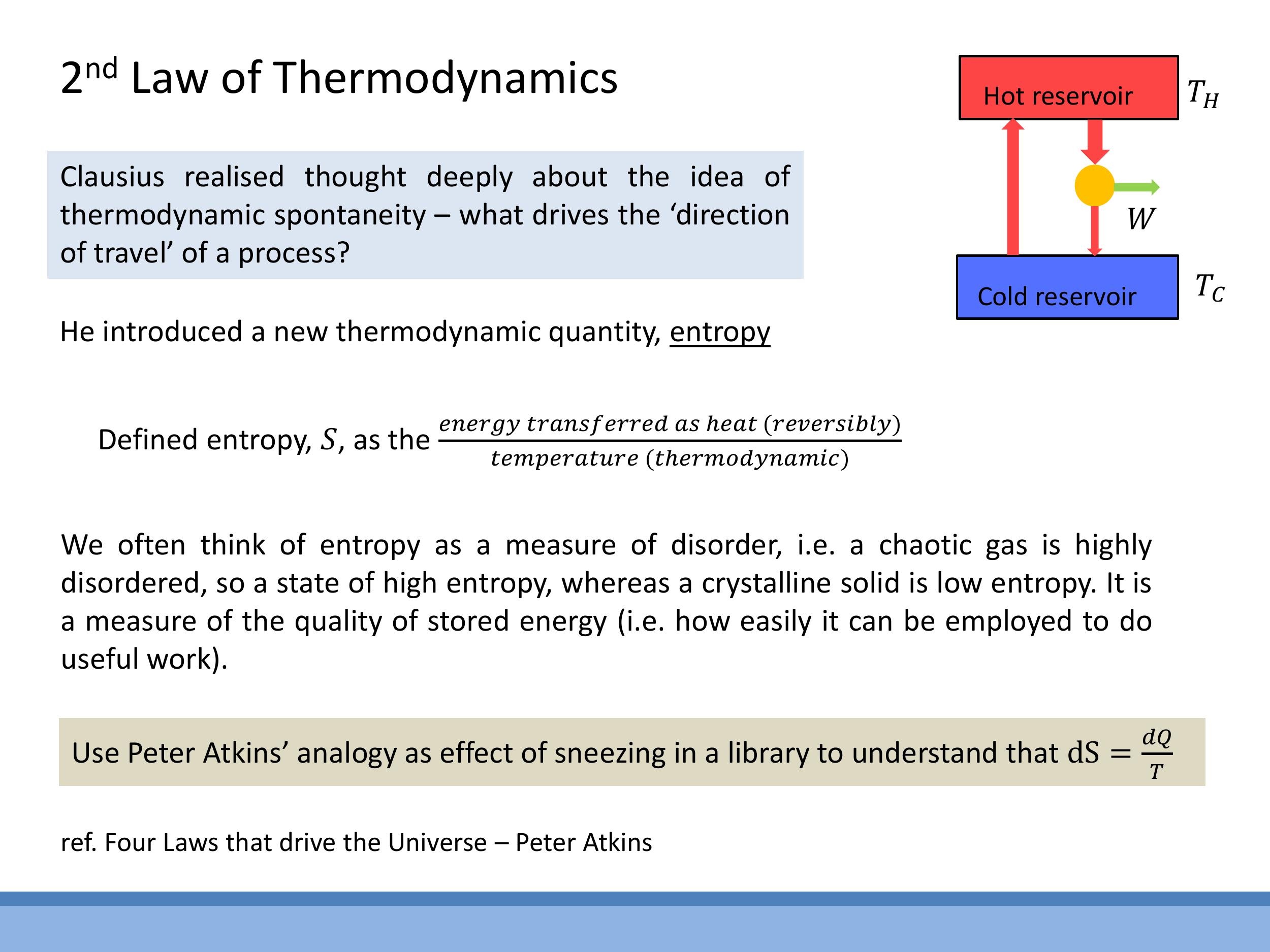

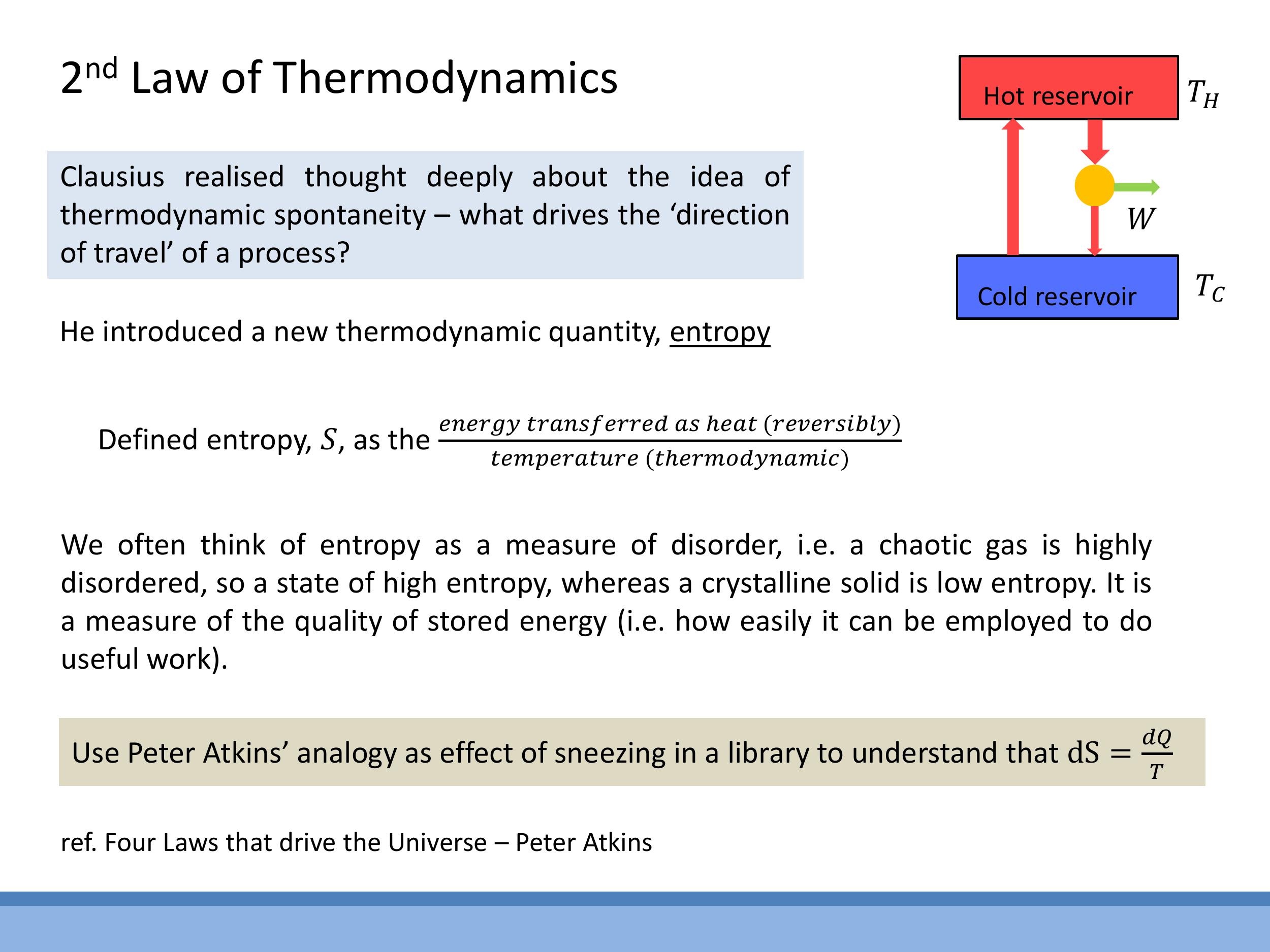

9) Entropy: concept and definition

Entropy ($S$) is a thermodynamic state function that quantifies the degree of disorder or the dispersal of energy within a system. A common intuition is that a gas, with its randomly moving particles, has higher entropy than a liquid, which in turn has higher entropy than an ordered crystalline solid. Another perspective views entropy as a measure of the "quality" of energy; high-quality, concentrated energy (e.g., sunlight) corresponds to lower entropy, while dispersed, low-quality energy (e.g., Earth's infrared emission) corresponds to higher entropy.

Formally, the change in entropy ($dS$) for a reversible process is defined by the differential relation:

$$

dS = \frac{dQ_{\text{rev}}}{T}

$$

where $dQ_{\text{rev}}$ is the infinitesimal amount of heat transferred reversibly, and $T$ is the absolute thermodynamic temperature. The $1/T$ factor can be understood by considering that a given amount of heat transfer ($dQ$) has a more significant disordering effect (i.e., causes a larger $dS$) at a lower temperature (when the system is more ordered and less energetic) than at a higher temperature (when the system is already more chaotic). This is analogous to a small disturbance having a greater impact in a quiet library than at a loud rock concert.

A fundamental consequence of the Second Law is that for any real (irreversible) process, the total entropy of the universe (system plus surroundings) always increases ($S_{\text{total}} > 0$). For idealised reversible processes, the total entropy remains constant ($S_{\text{total}} = 0$). While local decreases in entropy (e.g., the formation of an ordered crystal) are possible, they are always accompanied by a larger increase in entropy elsewhere in the surroundings, ensuring that the overall entropy of the universe never decreases.

10) Consolidation and bridge to next time

The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics established the concept of temperature ($T$). The First Law provided a framework for energy accounting through the relation $\Delta U = Q + W$, but it does not specify the direction of spontaneous processes. The Second Law, however, introduces entropy ($S$) as a new state function, which sets the direction of spontaneous change and defines the ultimate performance bounds for heat engines, encapsulated by the Carnot efficiency ($\varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}}$).

At this point, the fundamental concepts of heat engines versus refrigerators/heat pumps have been established, along with their respective efficiency ($\varepsilon$) and Coefficient of Performance (CoP) formulas. The construction of the Carnot cycle has been detailed, and its efficiency $\varepsilon = 1 - T_C/T_H$ has been derived as the theoretical maximum for any engine operating between two temperatures $T_H$ and $T_C$. Furthermore, entropy has been formally defined as $dS = dQ_{\text{rev}}/T$, with the understanding that the total entropy of the universe ($S_{\text{total}}$) increases for all real processes. The next steps will involve applying these tools to concrete thermodynamic cycles and calculations of efficiency, as well as exploring further applications of entropy to assess the feasibility and reversibility of various processes.

Key takeaways

Heat flow alone from a hot to a cold body does not produce useful work. Placing a working substance in a cyclic process between a hot reservoir and a cold reservoir allows for the extraction of useful work, where $W = Q_H - Q_C$.

The efficiency ($\varepsilon$) of a heat engine is defined as $\varepsilon = 1 - Q_C/Q_H$. In contrast, a refrigerator's Coefficient of Performance (CoP) is $Q_C/W$, which can exceed 1 because its function is to transfer heat rather than to create work.

The Carnot cycle, composed of two isothermal and two adiabatic reversible stages, represents the ideal heat engine. Its maximum efficiency, $\varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}} = 1 - T_C/T_H$, depends exclusively on the absolute temperatures of the hot ($T_H$) and cold ($T_C$) reservoirs. The Stirling cycle, which uses two isotherms and two isochoric processes, achieves the same ideal efficiency when operated reversibly between the same temperatures.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics has two equivalent statements:

- Clausius statement: Heat cannot spontaneously flow from a colder body to a hotter body.

- Kelvin statement: No cyclic device can completely convert heat from a single hot source into work; a cold sink is essential for continuous operation.

Entropy ($S$) quantifies the dispersal or "quality" of energy. Its formal definition for a reversible process is $dS = dQ_{\text{rev}}/T$. For any real (irreversible) process, the total entropy of the universe (system plus surroundings) always increases ($\Delta S_{\text{total}} > 0$); for reversible processes, it remains constant ($\Delta S_{\text{total}} = 0$).

## Lecture 11: Heat Engines and the Second Law (Part 1)

### 0) Orientation and learning outcomes

This lecture builds directly on preceding material from Lectures 7-10, which covered the First Law of Thermodynamics, its sign conventions for internal energy ($U$), heat ($Q$), and work ($W$), and the concepts of reversible and irreversible processes, including $P$-$V$ work. Previous topics also included adiabatic relations such as $PV^\gamma = \text{constant}$ and $TV^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}$, exemplified by the diesel "fire piston" demonstration. Today's focus shifts from simple heat flow to the principles of heat engines, defining their efficiency and the coefficient of performance (CoP). The lecture will construct the ideal Carnot cycle and derive its maximum possible efficiency, ultimately introducing the Second Law of Thermodynamics and the formal definition of entropy ($S$).

By the end of this lecture, students should be able to determine energy changes for each stage of a given heat-engine cycle, calculate the useful work extracted from a cycle using a $P$-$V$ diagram, recall and state the Kelvin and Clausius forms of the Second Law, and define entropy, explaining its relation $dS = dQ_{rev} / T$.

### 1) First Law recap and sign conventions

Internal energy ($U$) is a state function, meaning its value depends only on the current state of a system, irrespective of the path taken to reach that state. In contrast, heat ($Q$) and work ($W$) are processes, representing energy transfers that are path-dependent. The First Law of Thermodynamics, a statement of energy conservation, is expressed as $\Delta U = Q + W$. In this convention, $W$ is positive when work is done *on* the system (e.g., compression), and $Q$ is positive when heat *enters* the system. This contrasts with the differential form $dQ = dU + PdV$ previously encountered, where $PdV$ represents work done *by* the gas.

To illustrate, consider internal energy as a bank account balance: $Q$ and $W$ are the deposits or withdrawals that change the balance $\Delta U$. Heat refers to energy transfer driven by temperature differences, involving the chaotic motion of particles. Work, conversely, refers to energy transfer through the ordered motion of particles, such as the force exerted by a piston on a gas.

### 2) From “useless” heat flow to a heat engine

Consider a hot object connected to a cold object by a copper rod. Heat will spontaneously flow from the hot object to the cold object due to the temperature difference. However, this process yields no useful work. A heat engine, in contrast, is designed to operate between a hot reservoir at temperature $T_H$ and a cold reservoir at temperature $T_C$, extracting useful work ($W$) from the heat flow.

The operational principle of a heat engine requires a working substance (e.g., a gas or fluid) to undergo a cyclic process, returning to its initial state after each cycle. In doing so, the engine absorbs heat ($Q_H$) from the hot reservoir, converts a portion of it into useful work ($W$), and rejects the remaining heat ($Q_C$) to the cold reservoir. The energy balance for a complete cycle dictates that the useful work extracted is the difference between the heat absorbed and the heat rejected: $W = Q_H - Q_C$.

### 3) Efficiency of a heat engine

The efficiency ($\varepsilon$) of a heat engine quantifies how effectively it converts absorbed heat into useful work. It is defined as the ratio of the useful work output ($W$) to the total heat absorbed from the hot reservoir ($Q_H$).

This definition can be expanded using the energy balance $W = Q_H - Q_C$:

$$ \varepsilon = \frac{W}{Q_H} = \frac{Q_H - Q_C}{Q_H} = 1 - \frac{Q_C}{Q_H} $$

This formula demonstrates that the efficiency of any heat engine must always be less than 1 (or 100%). A fraction of the absorbed heat ($Q_C$) must always be rejected to the cold sink to complete the thermodynamic cycle, making perfect conversion of heat to work impossible.

### 4) Refrigerators and heat pumps (engines run in reverse)

A refrigerator or a heat pump operates as a heat engine in reverse. Instead of producing work from a temperature difference, external work ($W$) is supplied to drive heat "uphill," moving heat ($Q_C$) from a cold reservoir at $T_C$ to a hot reservoir at $T_H$. The total heat rejected to the hot reservoir ($Q_H$) is the sum of the work input and the heat extracted from the cold reservoir: $Q_H = W + Q_C$.

The performance of a refrigerator or heat pump is quantified by its Coefficient of Performance (CoP), rather than efficiency. For a refrigerator, the CoP is defined as the ratio of the heat extracted from the cold reservoir ($Q_C$) to the work input ($W$):

$$ \text{CoP}_{\text{fridge}} = \frac{Q_C}{W} = \frac{Q_C}{Q_H - Q_C} $$

Unlike engine efficiency, the CoP can be greater than 1. For instance, typical heat pumps often achieve a CoP of 3-5, meaning they can transfer 3 to 5 units of heat energy for every unit of electrical work supplied.

### 5) The Carnot cycle: the ideal reversible heat engine

To produce net useful work, a thermodynamic cycle on a $P$-$V$ diagram must enclose a non-zero area; a simple back-and-forth along a single isotherm would yield no net work. The Carnot cycle, an idealised and perfectly reversible heat engine, achieves this by combining four reversible stages.

The four reversible stages of the Carnot cycle are:

1. **Isothermal Expansion (a $\to$ b):** The working substance expands at a constant high temperature $T_H$, absorbing heat $Q_H$ from the hot reservoir. Since the internal energy of an ideal gas depends only on temperature, $\Delta U = 0$ for this isothermal process, meaning all absorbed heat is converted into work done *by* the gas.

2. **Adiabatic Expansion (b $\to$ c):** The system is thermally isolated, so no heat is exchanged ($Q = 0$). The gas continues to expand, doing work and consequently cooling from $T_H$ to $T_C$.

3. **Isothermal Compression (c $\to$ d):** The gas is compressed at a constant low temperature $T_C$, rejecting heat $Q_C$ to the cold reservoir.

4. **Adiabatic Compression (d $\to$ a):** The system is again thermally isolated ($Q = 0$). Work is done *on* the gas, causing its internal energy and temperature to increase, returning it to the initial high temperature $T_H$ and volume $V_a$.

In a $P$-$V$ diagram, the work done during expansion (stages a $\to$ b and b $\to$ c) is the area under those paths. The work done during compression (stages c $\to$ d and d $\to$ a) is the area under those paths. The net useful work extracted from the cycle is the enclosed area within the loop (the yellow region in the diagram), representing the difference between the work done by the gas and the work done on the gas.

Key thermodynamic terms used to describe processes include:

* **Isothermal:** Constant temperature ($T$).

* **Adiabatic:** No heat transfer ($Q = 0$).

* **Isochoric:** Constant volume ($V$).

* **Isobaric:** Constant pressure ($P$).

### 6) Deriving the Carnot efficiency $\varepsilon = 1 - T_C/T_H$

The Carnot efficiency can be derived by considering the heat exchanges during the isothermal stages and the relationships between volumes during the adiabatic stages.

For the isothermal expansion (a $\to$ b) at $T_H$, where $\Delta U = 0$, the heat absorbed $Q_H$ is equal to the work done by the gas:

$$ Q_H = \int_{V_a}^{V_b} P \, dV = n R T_H \ln\left(\frac{V_b}{V_a}\right) $$

Similarly, for the isothermal compression (c $\to$ d) at $T_C$, the heat rejected $Q_C$ is:

$$ Q_C = n R T_C \ln\left(\frac{V_c}{V_d}\right) $$

The ratio of these heats is then:

$$ \frac{Q_C}{Q_H} = \frac{T_C \ln(V_c/V_d)}{T_H \ln(V_b/V_a)} $$

The adiabatic stages (b $\to$ c and d $\to$ a) are governed by the relation $TV^{\gamma-1} = \text{constant}$. Applying this to the transitions:

$$ T_H V_b^{\gamma-1} = T_C V_c^{\gamma-1} $$

$$ T_H V_a^{\gamma-1} = T_C V_d^{\gamma-1} $$

Dividing these two equations yields:

$$ \left(\frac{V_b}{V_a}\right)^{\gamma-1} = \left(\frac{V_c}{V_d}\right)^{\gamma-1} $$

This simplifies to the crucial relation $\frac{V_b}{V_a} = \frac{V_c}{V_d}$. Substituting this back into the heat ratio equation, the logarithmic terms cancel:

$$ \frac{Q_C}{Q_H} = \frac{T_C}{T_H} $$

Finally, substituting this into the definition of efficiency $\varepsilon = 1 - \frac{Q_C}{Q_H}$ gives the Carnot efficiency:

$$ \varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}} = 1 - \frac{T_C}{T_H} $$

This formula demonstrates that the maximum possible efficiency of a heat engine depends solely on the absolute temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs, and is independent of the working substance or the specific design of the engine.

*Side Note:* There was a mislabelling of volumes ($V_a, V_b, V_c, V_d$) on the $P$-$V$ diagrams in the original lecture slides, which will be corrected in the uploaded notes.

### 7) The Stirling cycle and live engine demonstration

The Stirling cycle is another ideal reversible heat engine cycle. Its structure on a $P$-$V$ diagram consists of two isothermal processes (expansion at $T_H$ and compression at $T_C$) connected by two isochoric (constant volume) heat transfer steps. An ideal Stirling engine operating reversibly between the same hot ($T_H$) and cold ($T_C$) reservoirs achieves the same maximum efficiency bound as the Carnot cycle: $\varepsilon = 1 - T_C/T_H$.

A live demonstration with Stirling engines visually illustrates this principle. When an engine was placed on hot water (approaching $100\,\text{°C}$ for $T_H$, with the top plate at room temperature $T_C \approx 20\,\text{°C}$), it accelerated rapidly. This is due to the large temperature difference ($\Delta T \approx 80\,\text{K}$), leading to a higher efficiency. In contrast, when another engine was placed on ice water ($T_C = 0\,\text{°C}$, with the top plate at room temperature $T_H \approx 20\,\text{°C}$), it ran much more slowly or struggled to operate. The smaller temperature difference ($\Delta T \approx 20\,\text{K}$) in this case resulted in poorer performance. This speed difference directly reflects the dependence of efficiency on the temperature difference between the hot and cold reservoirs, demonstrating that a larger temperature difference yields greater available work per cycle.

### 8) The Second Law: Kelvin and Clausius statements and equivalence

The Second Law of Thermodynamics establishes the direction of spontaneous processes and places fundamental limits on the efficiency of heat engines. It can be stated in two equivalent forms:

The **Clausius statement** asserts that heat does not pass spontaneously from a cold body to a hot body. The term "spontaneous" here refers to the thermodynamic tendency towards a more favourable, higher entropy state, not necessarily an instantaneous process.

The **Kelvin (Thomson) statement** declares that no cyclic process is possible that takes heat from a single hot source and converts it completely into work. This implies the necessity of a cold sink; some energy must always be rejected to a cold reservoir to complete a cycle and extract useful work.

These two statements are equivalent, meaning that if one were false, it would be possible to construct a device that violates the other. They represent two complementary aspects of the same fundamental physical law.

### 9) Entropy: concept and definition

Entropy ($S$) is a thermodynamic state function that quantifies the degree of disorder or the dispersal of energy within a system. A common intuition is that a gas, with its randomly moving particles, has higher entropy than a liquid, which in turn has higher entropy than an ordered crystalline solid. Another perspective views entropy as a measure of the "quality" of energy; high-quality, concentrated energy (e.g., sunlight) corresponds to lower entropy, while dispersed, low-quality energy (e.g., Earth's infrared emission) corresponds to higher entropy.

Formally, the change in entropy ($dS$) for a reversible process is defined by the differential relation:

$$ dS = \frac{dQ_{\text{rev}}}{T} $$

where $dQ_{\text{rev}}$ is the infinitesimal amount of heat transferred reversibly, and $T$ is the absolute thermodynamic temperature. The $1/T$ factor can be understood by considering that a given amount of heat transfer ($dQ$) has a more significant disordering effect (i.e., causes a larger $dS$) at a lower temperature (when the system is more ordered and less energetic) than at a higher temperature (when the system is already more chaotic). This is analogous to a small disturbance having a greater impact in a quiet library than at a loud rock concert.

A fundamental consequence of the Second Law is that for any real (irreversible) process, the total entropy of the universe (system plus surroundings) always increases ($S_{\text{total}} > 0$). For idealised reversible processes, the total entropy remains constant ($S_{\text{total}} = 0$). While local decreases in entropy (e.g., the formation of an ordered crystal) are possible, they are always accompanied by a larger increase in entropy elsewhere in the surroundings, ensuring that the overall entropy of the universe never decreases.

### 10) Consolidation and bridge to next time

The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics established the concept of temperature ($T$). The First Law provided a framework for energy accounting through the relation $\Delta U = Q + W$, but it does not specify the direction of spontaneous processes. The Second Law, however, introduces entropy ($S$) as a new state function, which sets the direction of spontaneous change and defines the ultimate performance bounds for heat engines, encapsulated by the Carnot efficiency ($\varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}}$).

At this point, the fundamental concepts of heat engines versus refrigerators/heat pumps have been established, along with their respective efficiency ($\varepsilon$) and Coefficient of Performance (CoP) formulas. The construction of the Carnot cycle has been detailed, and its efficiency $\varepsilon = 1 - T_C/T_H$ has been derived as the theoretical maximum for any engine operating between two temperatures $T_H$ and $T_C$. Furthermore, entropy has been formally defined as $dS = dQ_{\text{rev}}/T$, with the understanding that the total entropy of the universe ($S_{\text{total}}$) increases for all real processes. The next steps will involve applying these tools to concrete thermodynamic cycles and calculations of efficiency, as well as exploring further applications of entropy to assess the feasibility and reversibility of various processes.

## Key takeaways

Heat flow alone from a hot to a cold body does not produce useful work. Placing a working substance in a cyclic process between a hot reservoir and a cold reservoir allows for the extraction of useful work, where $W = Q_H - Q_C$.

The efficiency ($\varepsilon$) of a heat engine is defined as $\varepsilon = 1 - Q_C/Q_H$. In contrast, a refrigerator's Coefficient of Performance (CoP) is $Q_C/W$, which can exceed 1 because its function is to transfer heat rather than to create work.

The Carnot cycle, composed of two isothermal and two adiabatic reversible stages, represents the ideal heat engine. Its maximum efficiency, $\varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}} = 1 - T_C/T_H$, depends exclusively on the absolute temperatures of the hot ($T_H$) and cold ($T_C$) reservoirs. The Stirling cycle, which uses two isotherms and two isochoric processes, achieves the same ideal efficiency when operated reversibly between the same temperatures.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics has two equivalent statements:

* **Clausius statement:** Heat cannot spontaneously flow from a colder body to a hotter body.

* **Kelvin statement:** No cyclic device can completely convert heat from a single hot source into work; a cold sink is essential for continuous operation.

Entropy ($S$) quantifies the dispersal or "quality" of energy. Its formal definition for a reversible process is $dS = dQ_{\text{rev}}/T$. For any real (irreversible) process, the total entropy of the universe (system plus surroundings) always increases ($\Delta S_{\text{total}} > 0$); for reversible processes, it remains constant ($\Delta S_{\text{total}} = 0$).