Lecture 12: Heat Engines and the Second Law (part 2)

0) Orientation, learning outcomes, and bridge from last time

This lecture builds upon the concepts introduced in "Heat Engines (part 1)", which covered thermodynamic cycles on P-V diagrams, the distinction between reversible and irreversible processes, and adiabats. Today's focus is on the formal statements of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, the introduction of entropy ($S$) as a new state function, the use of T-S diagrams, and practical calculations of entropy for various processes.

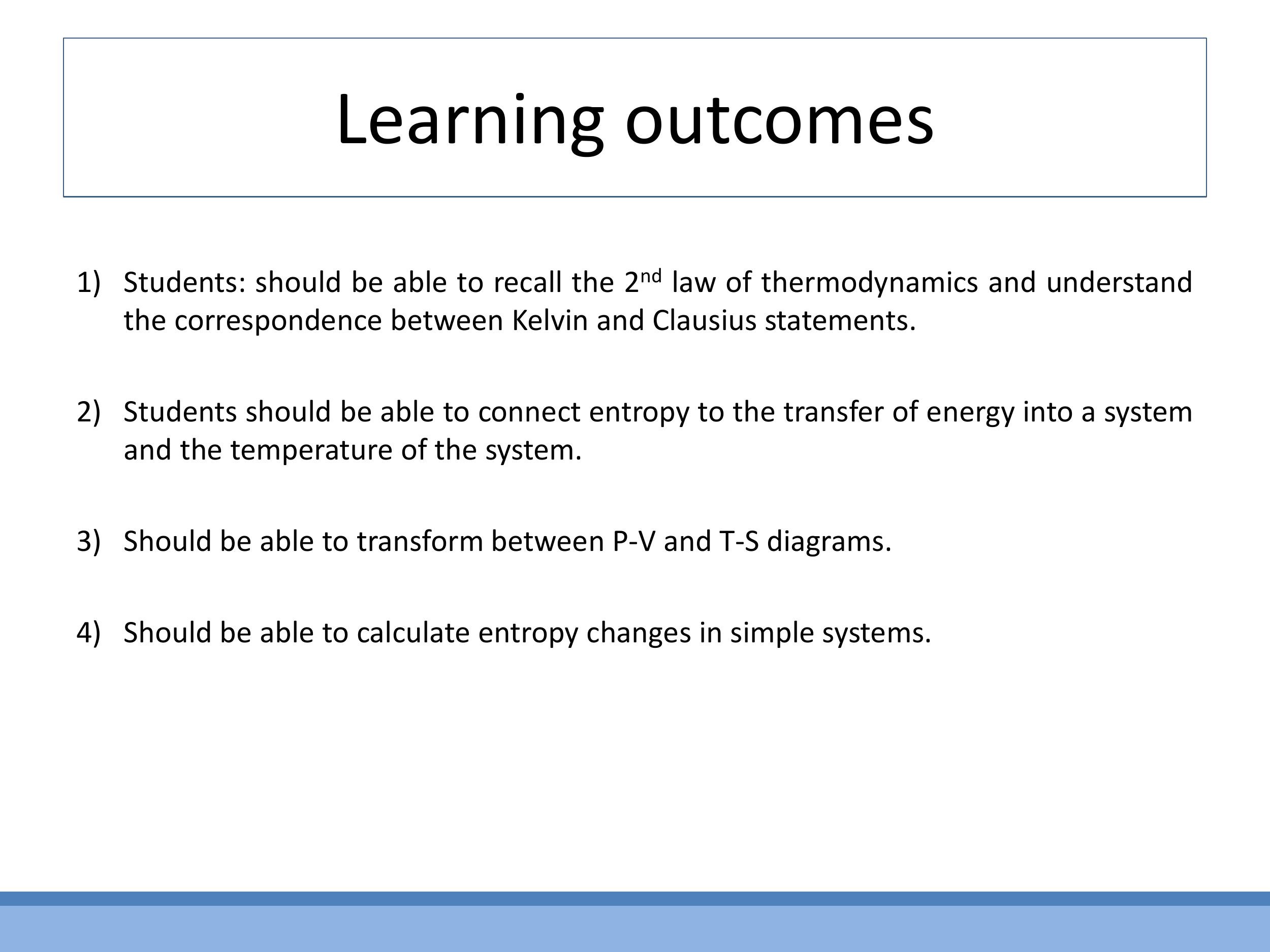

By the end of this lecture, students should be able to recall the Second Law and understand the equivalence between its Kelvin and Clausius statements. They will connect entropy to heat transfer and absolute temperature through the relationship $\text{d}S = \text{d}Q_{\text{rev}}/T$. Furthermore, students will learn to transform a Carnot cycle between P-V and T-S descriptions and calculate entropy changes in simple, representative processes, including both reversible and irreversible examples.

1) Useful work needs a cycle: the Carnot picture (quick recap)

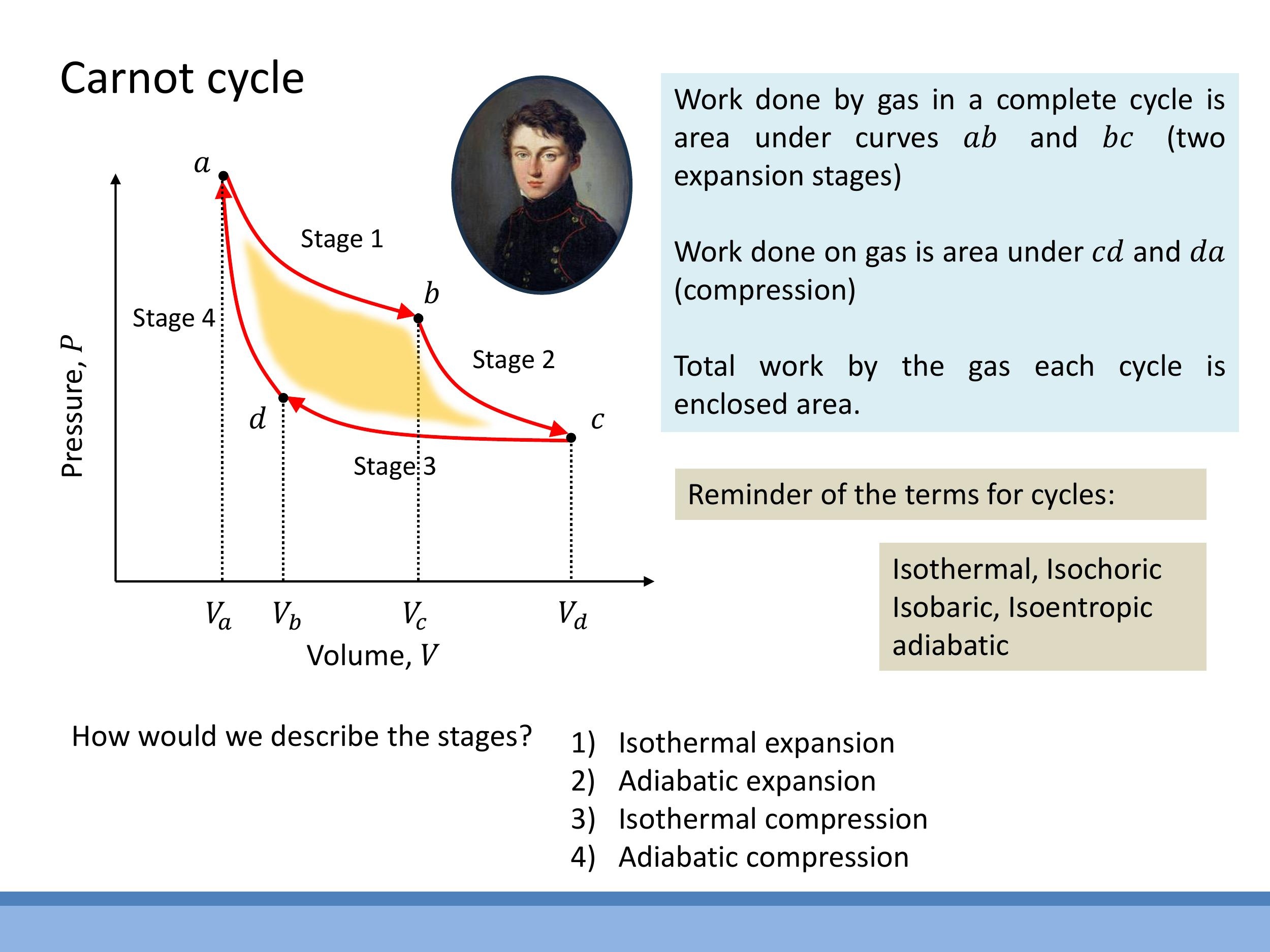

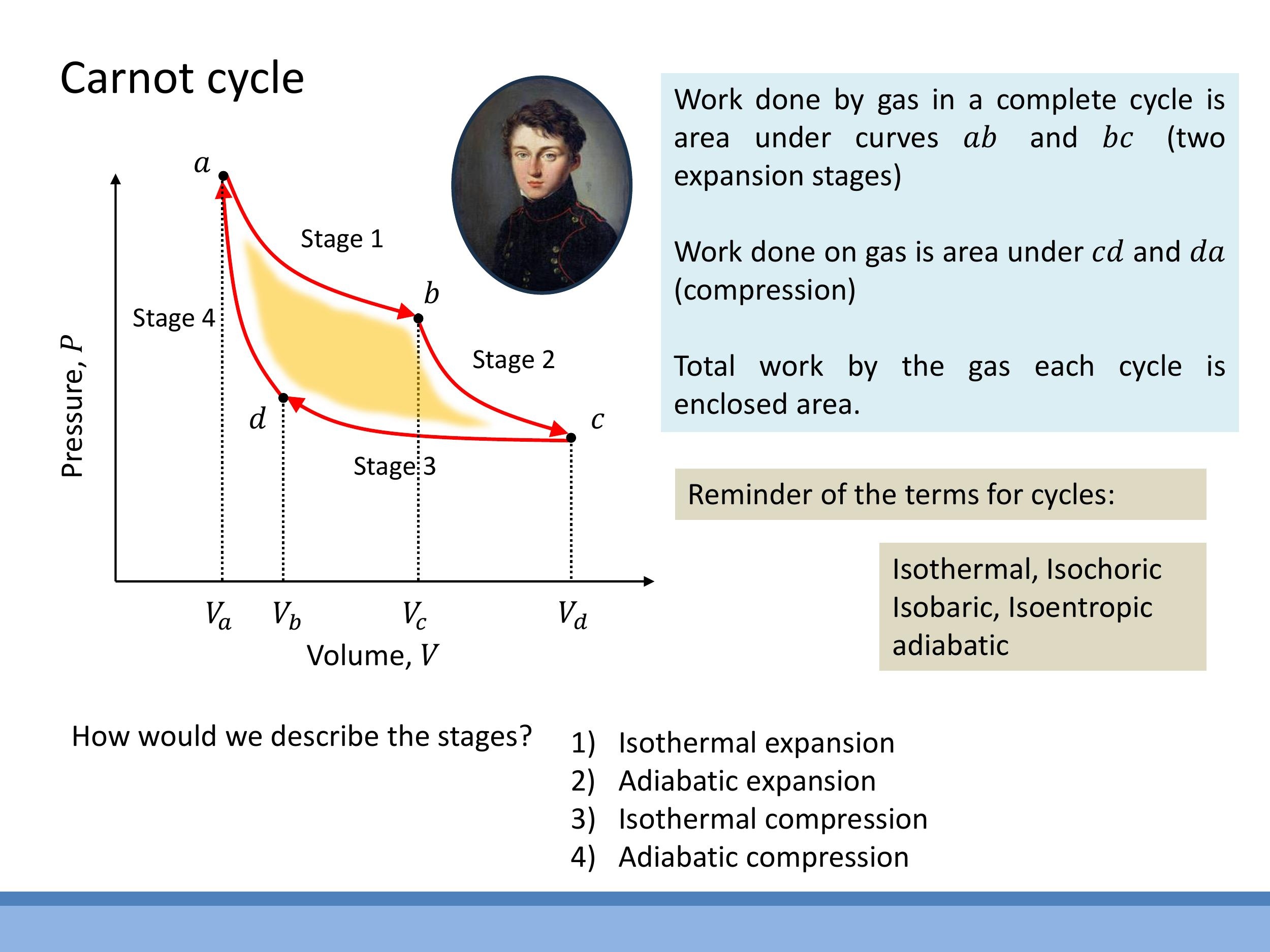

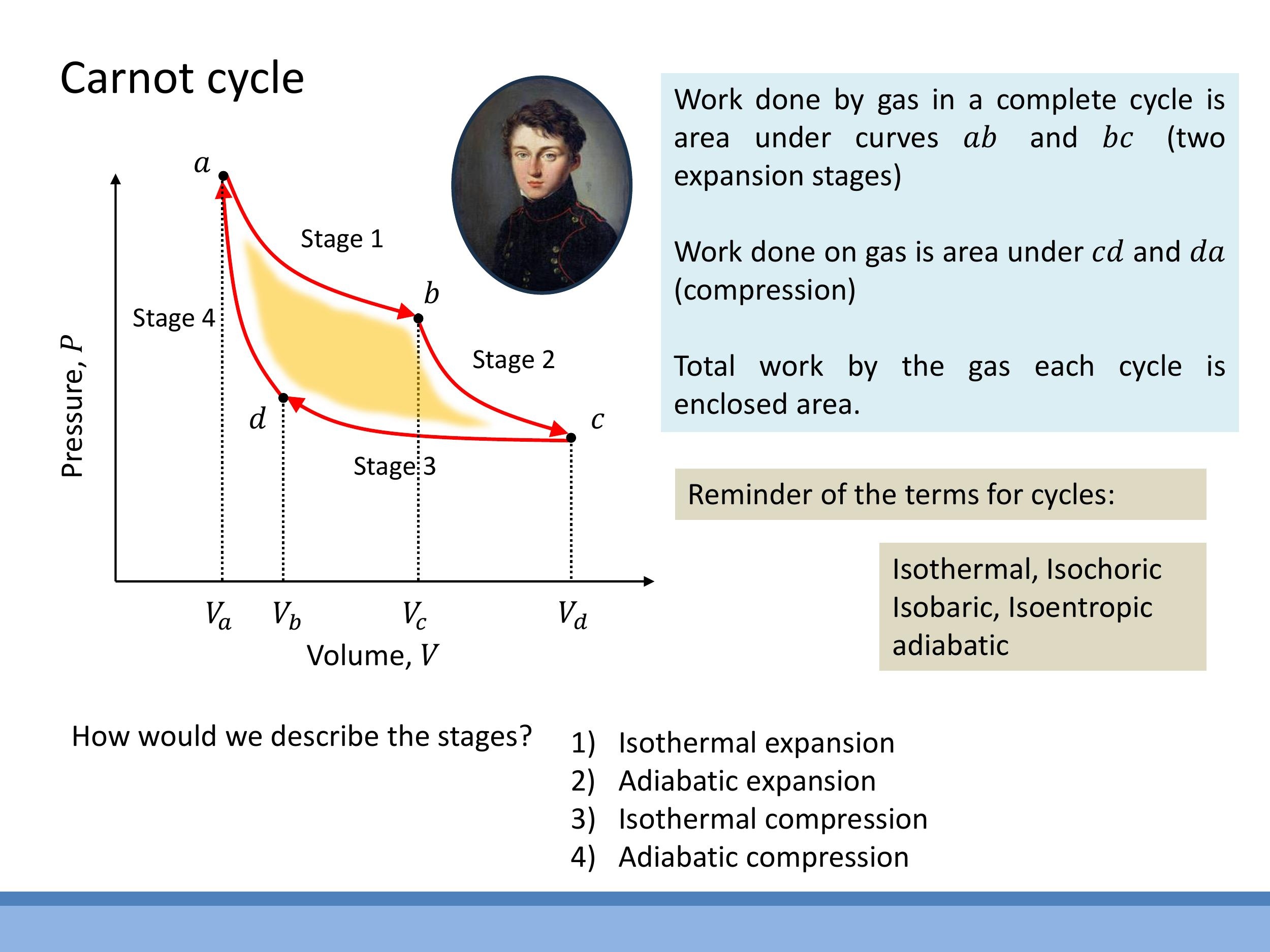

For a system to perform repeated useful work, its working substance must undergo a cyclic process, returning to its initial state. The net work performed by such a cycle is represented by the area enclosed by the cycle's path on a P-V diagram.

The ideal Carnot cycle consists of four reversible steps. It begins with an isothermal expansion at a high temperature $T_H$, during which the system absorbs heat $Q_H$ and performs work, with no change in internal energy ($\Delta U = 0$, so $Q_H = W_{\text{by}}$). This is followed by an adiabatic expansion, where no heat is exchanged ($Q=0$), and the gas cools to a lower temperature $T_C$ while continuing to do work. The third step is an isothermal compression at $T_C$, during which heat $Q_C$ is rejected to a cold reservoir. Finally, an adiabatic compression returns the system to its initial state, with no heat exchange ($Q=0$), as work is done on the gas, raising its temperature back to $T_H$. The efficiency of a reversible Carnot engine is given by $\varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}} = 1 - T_C/T_H$, depending solely on the absolute temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs. The Stirling cycle, while using isochoric (constant volume) processes instead of adiabats, shares this same ideal efficiency when reversible and operating between the same two temperatures, $T_H$ and $T_C$.

2) Vocabulary refresh for processes

Thermodynamic processes are defined by which state variables remain constant or how heat transfer occurs. An isothermal process maintains a constant temperature ($T$). An isochoric process occurs at constant volume ($V$). An isobaric process maintains constant pressure ($P$). An isentropic process occurs at constant entropy ($S$). An adiabatic process is characterised by no heat transfer ($\text{d}Q = 0$).

3) The Second Law: Kelvin and Clausius statements and why they’re equivalent

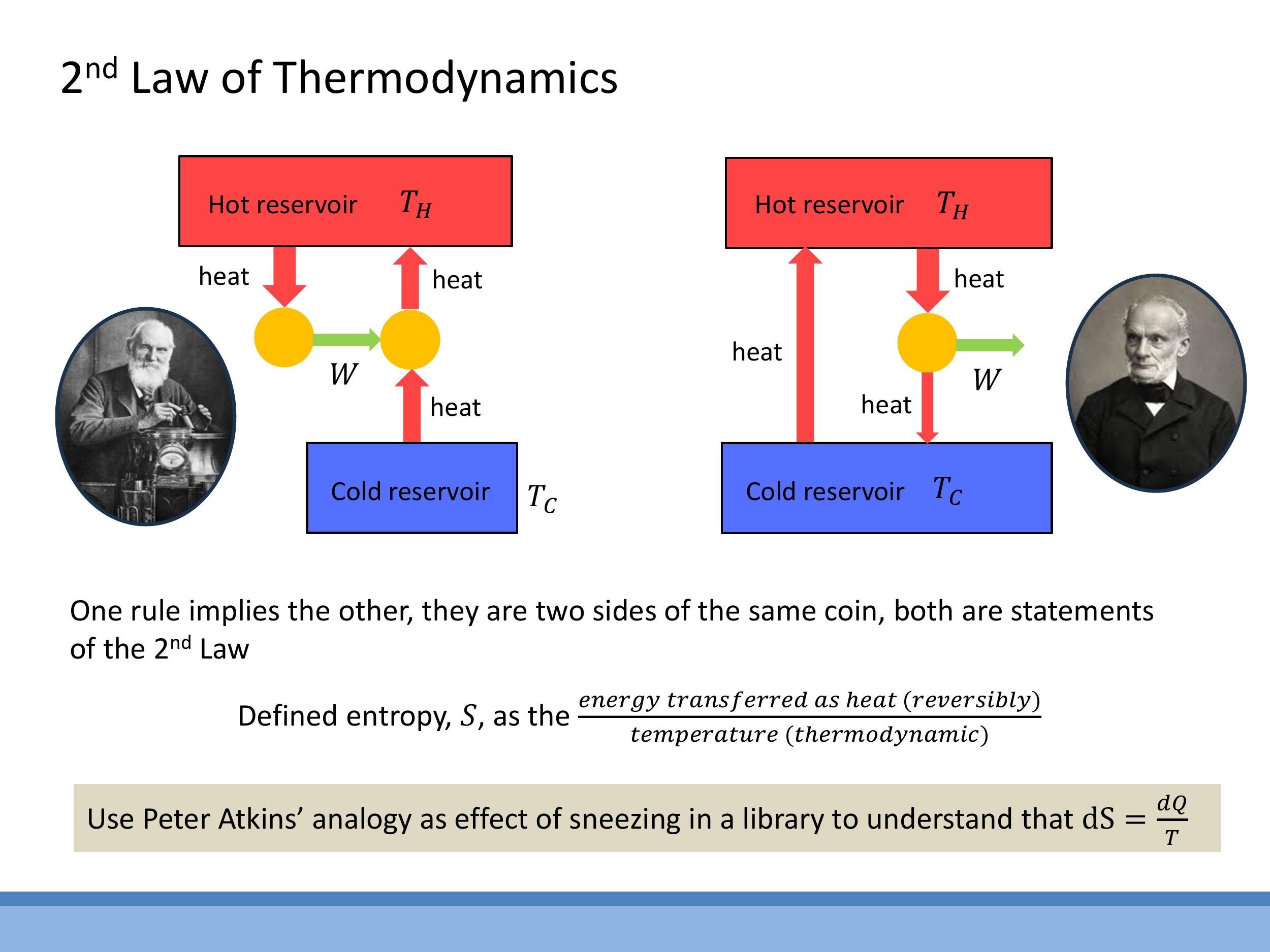

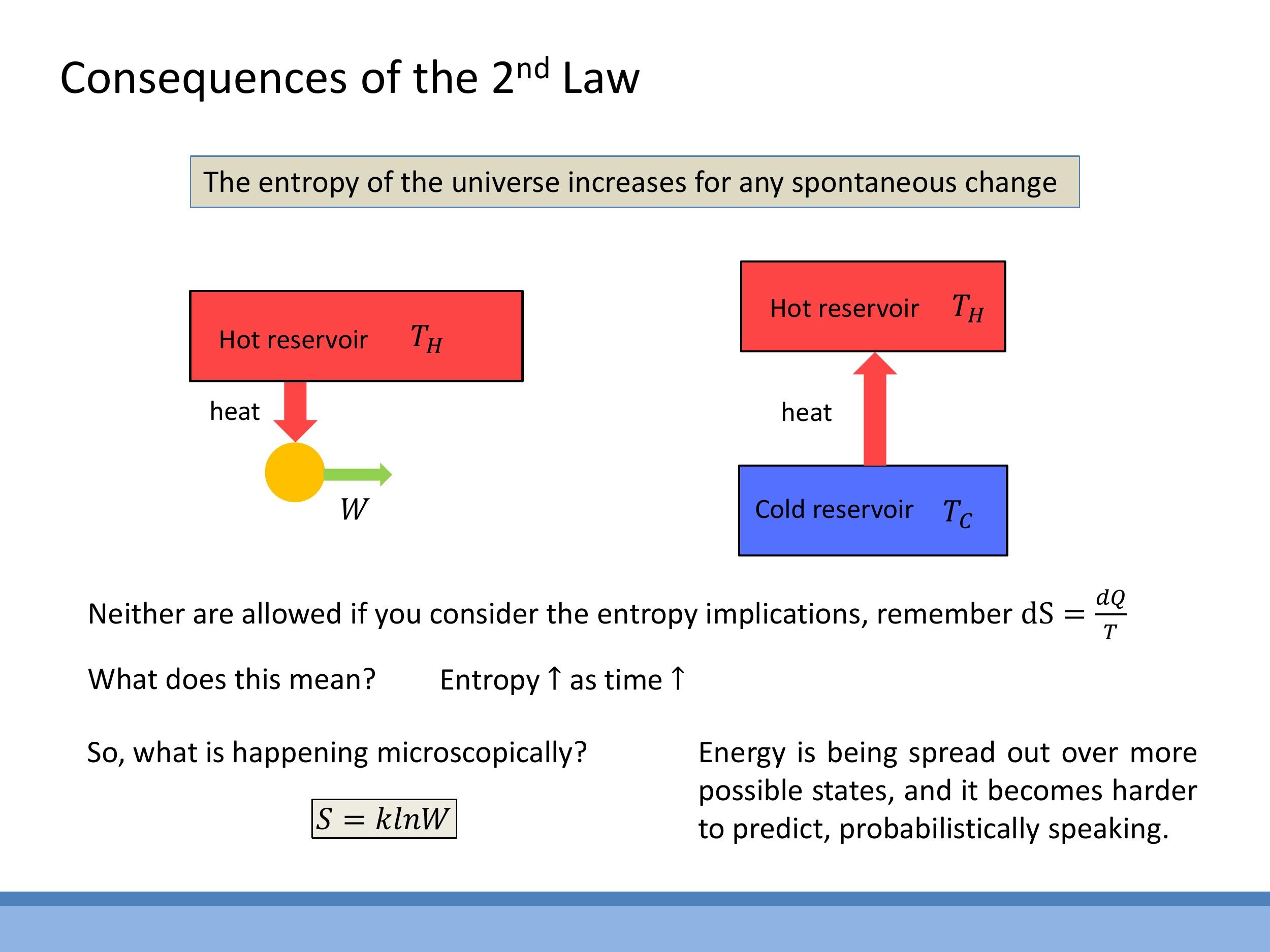

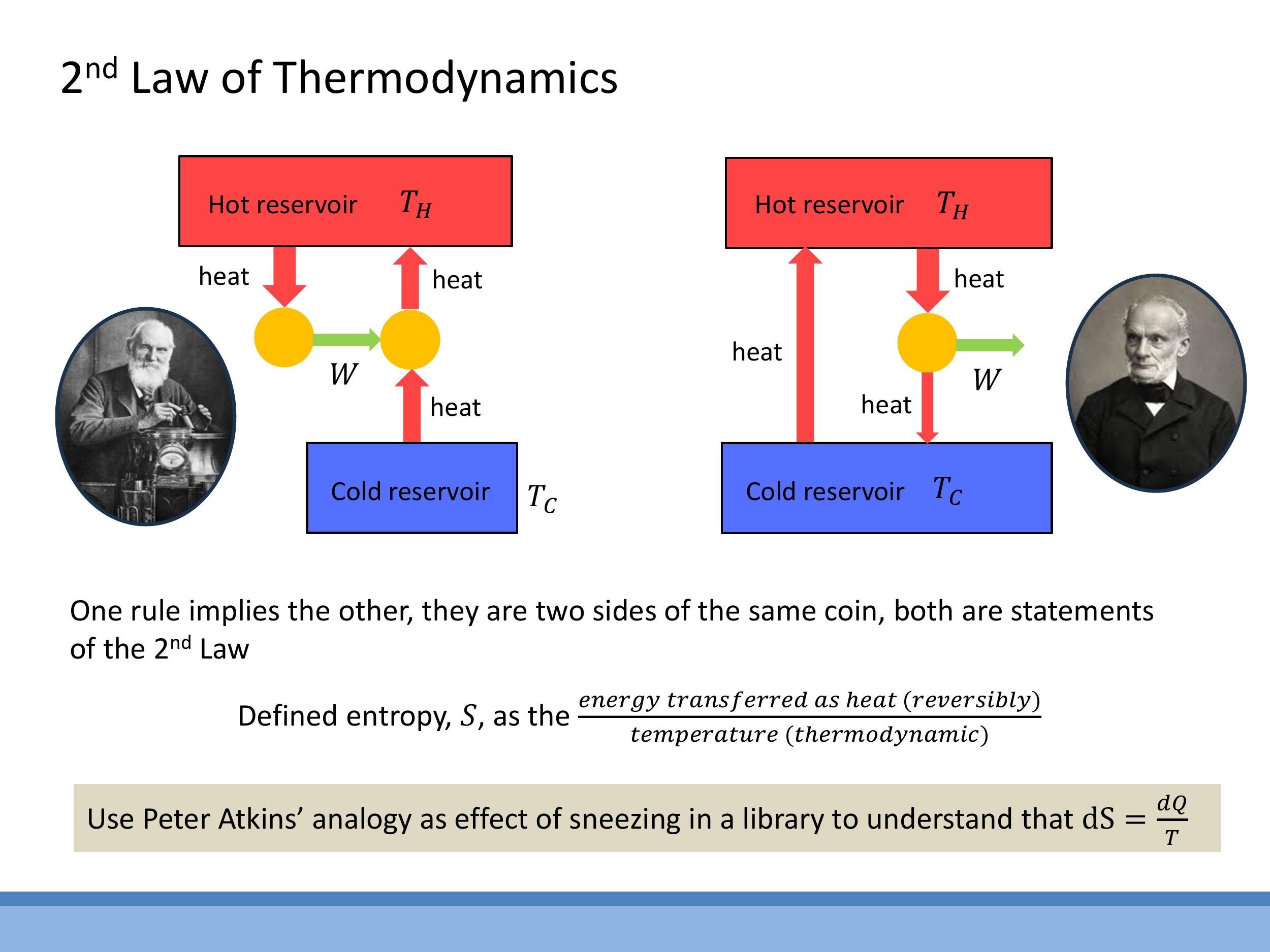

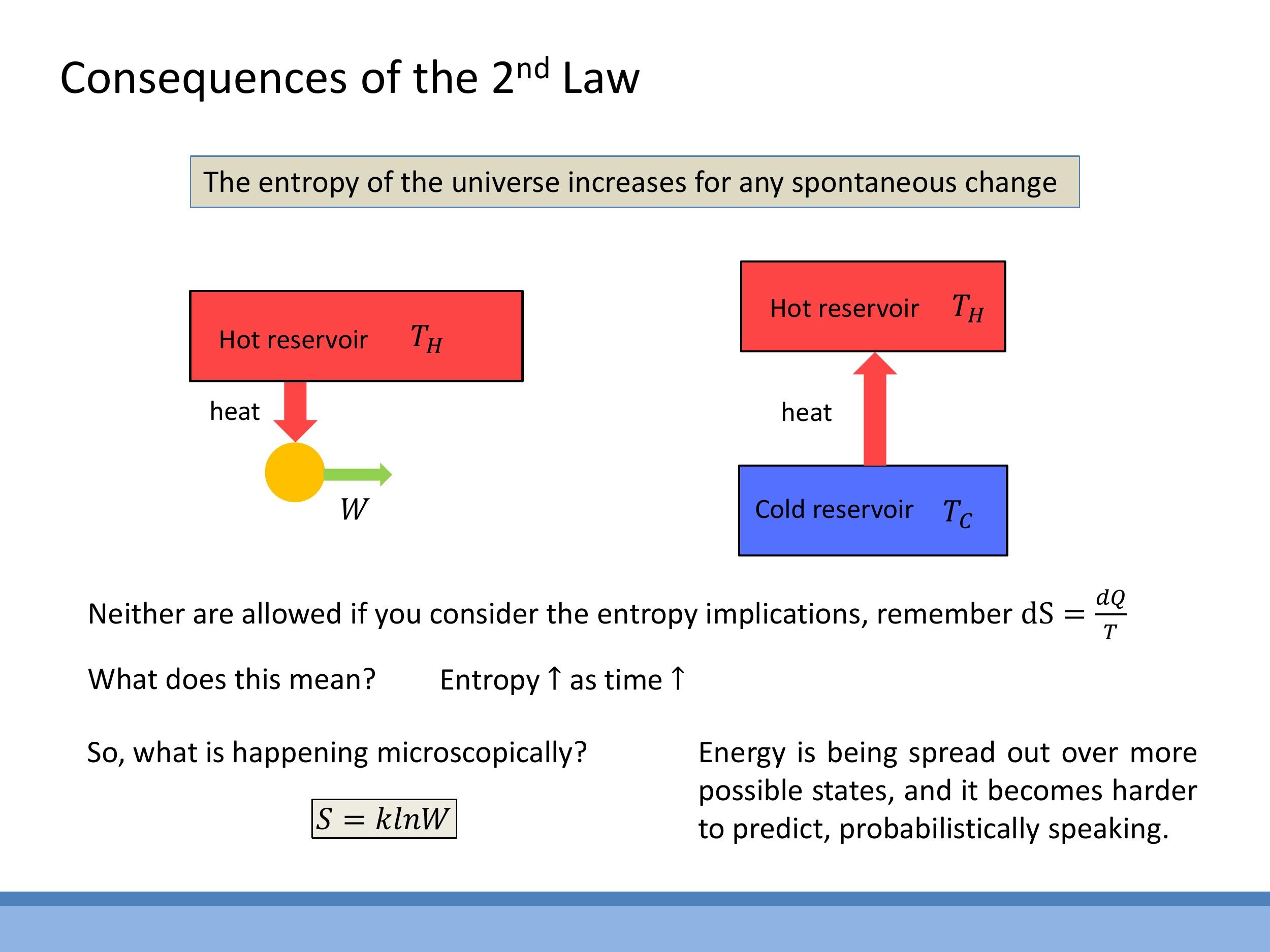

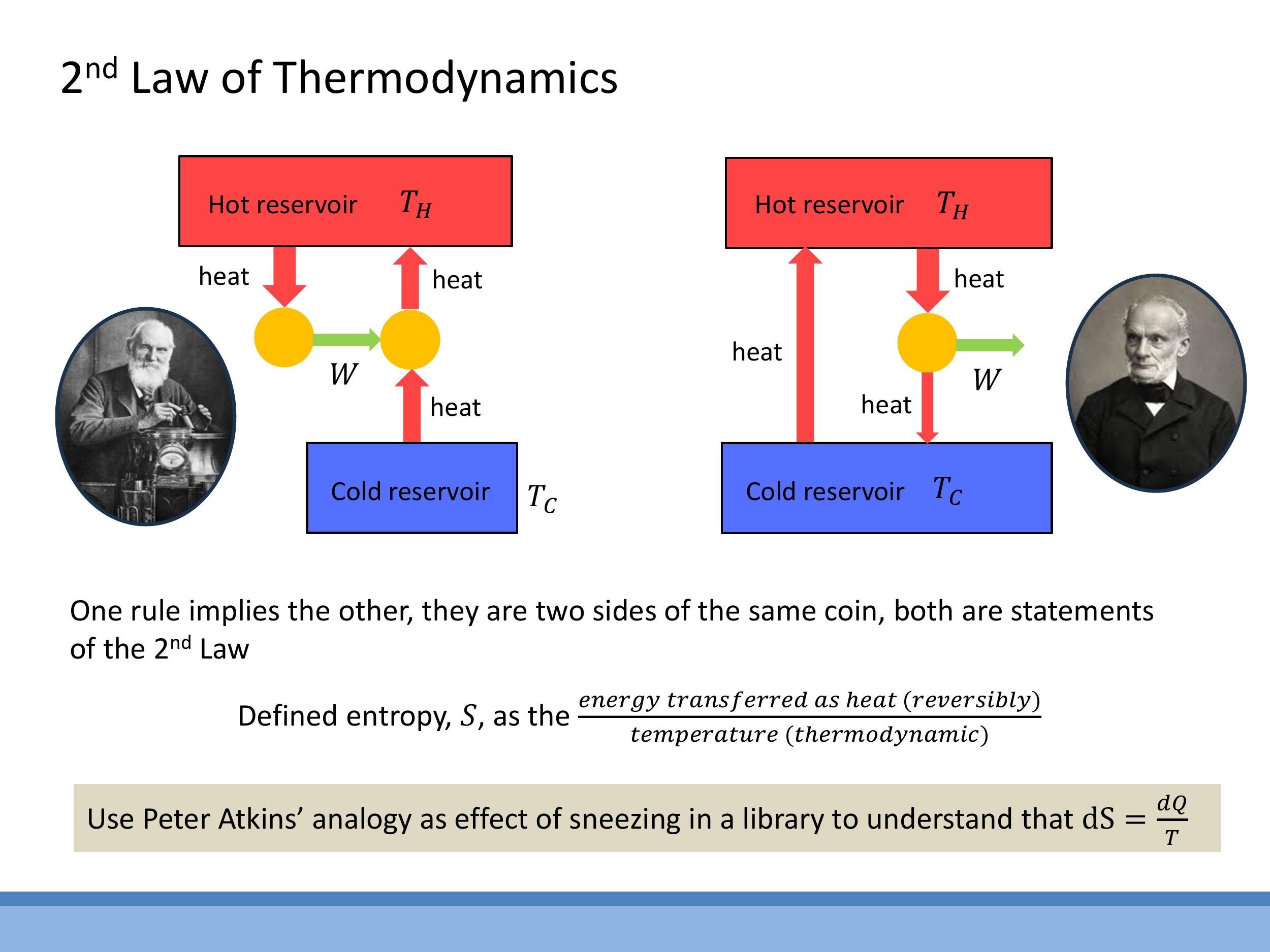

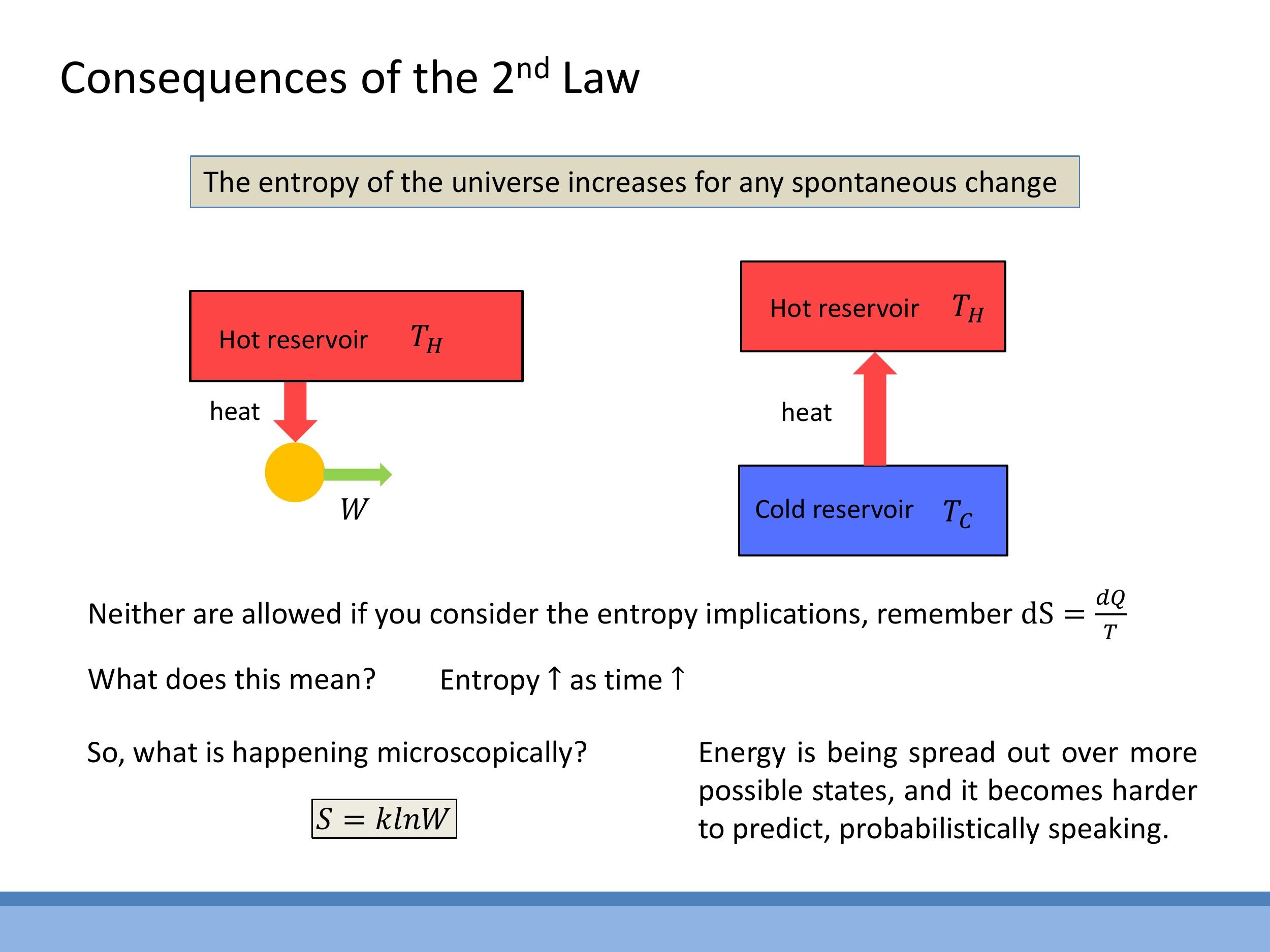

The Second Law of Thermodynamics places fundamental limits on the conversion of heat into work and dictates the direction of spontaneous processes. It can be expressed through two equivalent statements.

The Kelvin (Thomson) statement asserts that no cyclic device can convert all the heat absorbed from a single hot source entirely into work; a cold sink is always necessary for a heat engine to operate. This means that 100% efficient heat engines are impossible. The Clausius statement declares that heat does not pass spontaneously from a colder body to a hotter body. To transfer heat "uphill" from a cold reservoir to a hot one (as in a refrigerator), external work must be performed on the system. These two statements are equivalent: if one were false, it would be possible to construct a device that violates the other. Thus, they represent two different facets of the same fundamental physical law.

4) Entropy S: what it measures and its definitions

Entropy ($S$) is a thermodynamic state function that quantifies the disorder or randomness of a system. Physically, it can be understood in several ways: as a measure of the disorder (e.g., a gas exhibits higher entropy than a liquid, which in turn has higher entropy than a solid); as a measure of how widely energy is distributed among accessible microstates of a system; or conversely, as an inverse measure of energy quality, where high-quality, concentrated energy is low-entropy, while dispersed "waste heat" is high-entropy.

The thermodynamic definition of a change in entropy is given by $\text{d}S = \text{d}Q_{\text{rev}} / T$, where $\text{d}Q_{\text{rev}}$ is the infinitesimal amount of heat transferred reversibly, and $T$ is the absolute temperature. This $1/T$ dependence implies that the same amount of heat transfer ($\text{d}Q$) causes a greater change in entropy ($\text{d}S$) in a colder system (low $T$) than in a hotter system (high $T$), similar to how a sneeze causes a larger disturbance in a quiet library than on a busy street. For context, the statistical definition of entropy, $S = k \ln W$ (Boltzmann's equation), relates entropy to the natural logarithm of the number of accessible microstates ($W$) where $k$ is Boltzmann's constant, but this is not used for calculations in this course.

5) The Carnot cycle on a T-S diagram and a simpler route to ε

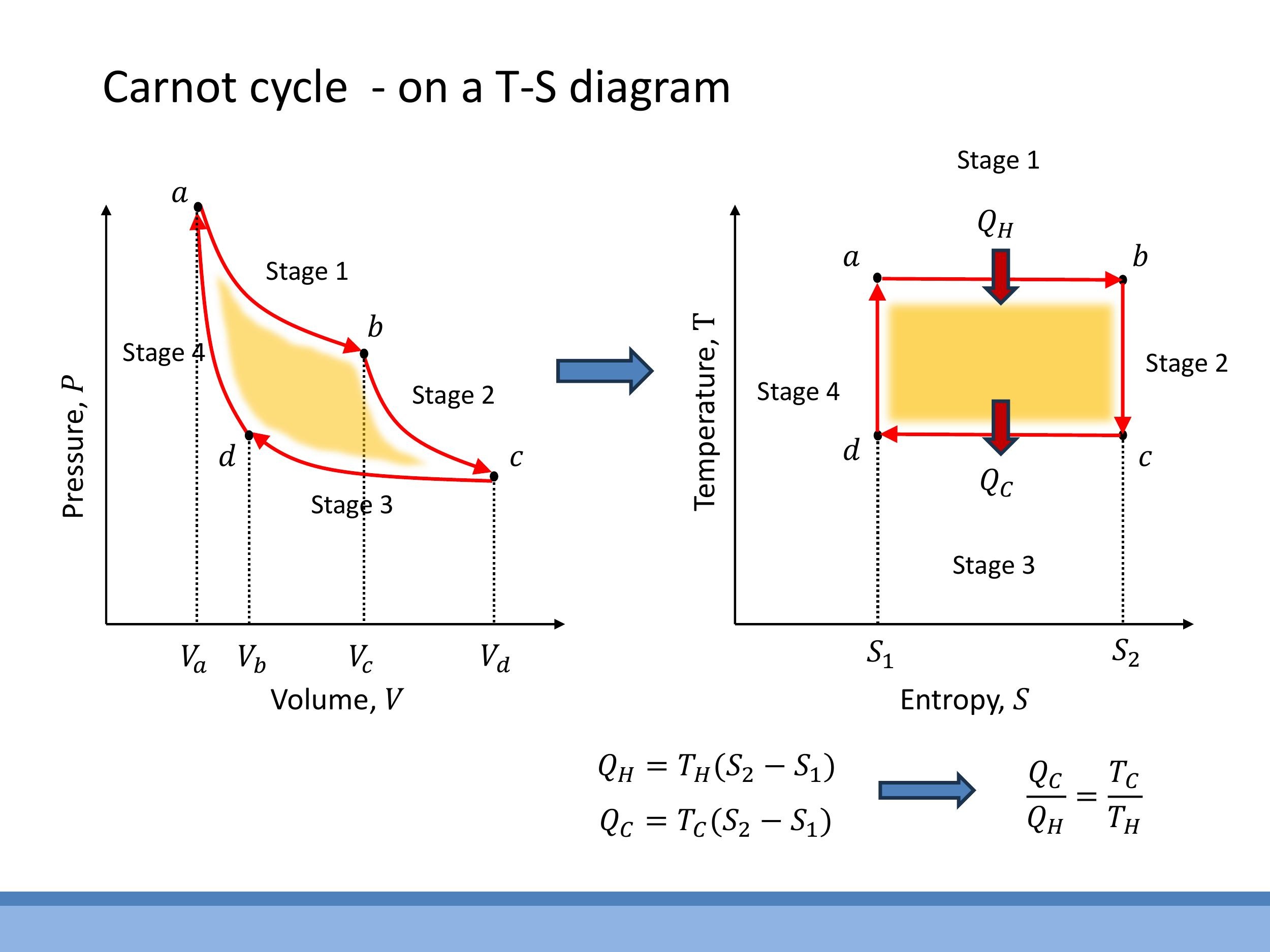

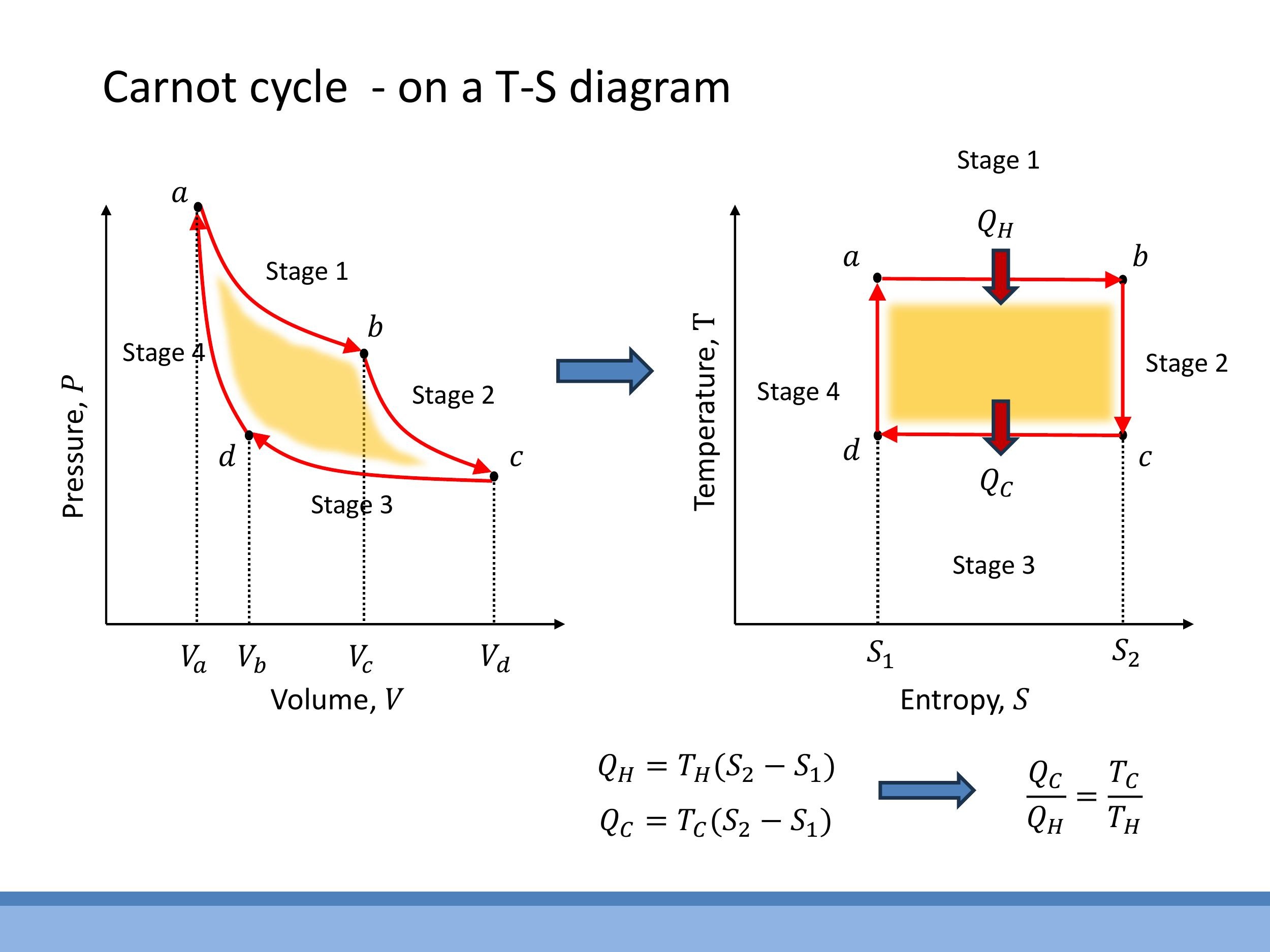

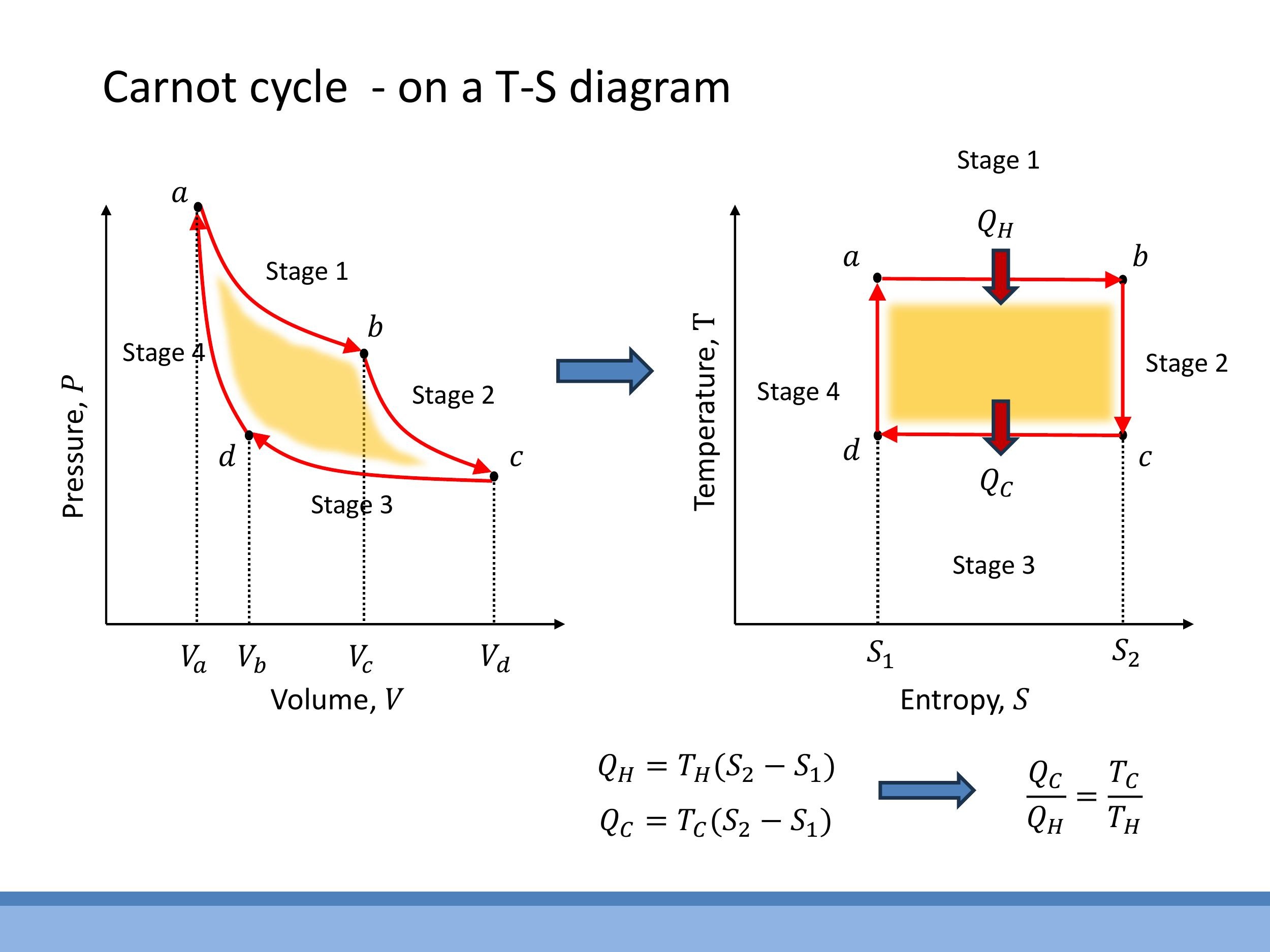

The Carnot cycle, when depicted on a Temperature-Entropy ($T-S$) diagram, provides a simplified visual and algebraic representation compared to a P-V diagram.

On a $T-S$ diagram, the four reversible steps of the Carnot cycle form a perfect rectangle. The isothermal legs appear as horizontal lines: at $T_H$ for expansion (entropy increases from $S_1$ to $S_2$) and at $T_C$ for compression (entropy decreases from $S_2$ to $S_1$). The adiabatic, reversible legs are vertical lines, as $\text{d}Q = 0$ implies $\text{d}S = 0$, connecting the two isothermal temperatures $T_H$ and $T_C$.

In this representation, the heat transferred during an isothermal process is simply the area under the corresponding horizontal line. Thus, the heat absorbed from the hot reservoir is $Q_H = T_H \Delta S$, and the heat rejected to the cold reservoir is $Q_C = T_C \Delta S$, where $\Delta S = S_2 - S_1$. This directly leads to the ratio $Q_C/Q_H = T_C/T_H$, which, when substituted into the general efficiency formula, yields the Carnot efficiency $\varepsilon = 1 - T_C/T_H$. This graphical representation on a $T-S$ diagram significantly compresses the algebra, making the derivation of the Carnot efficiency immediate and intuitive, while still describing the same underlying physics as the P-V diagram.

6) Calculating entropy changes: representative worked cases

6.1 Reversible phase change at fixed T: melting ice at 0 °C

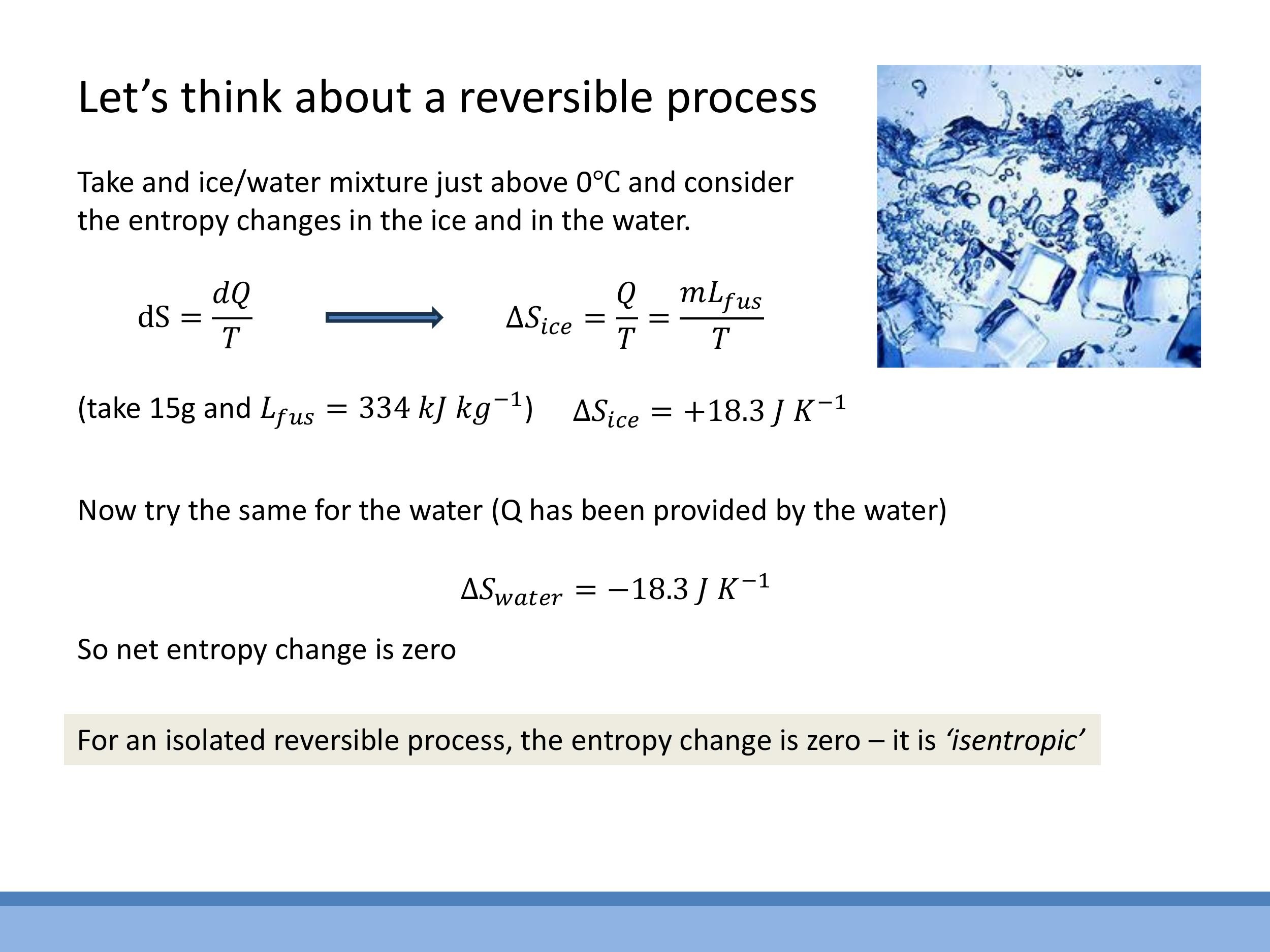

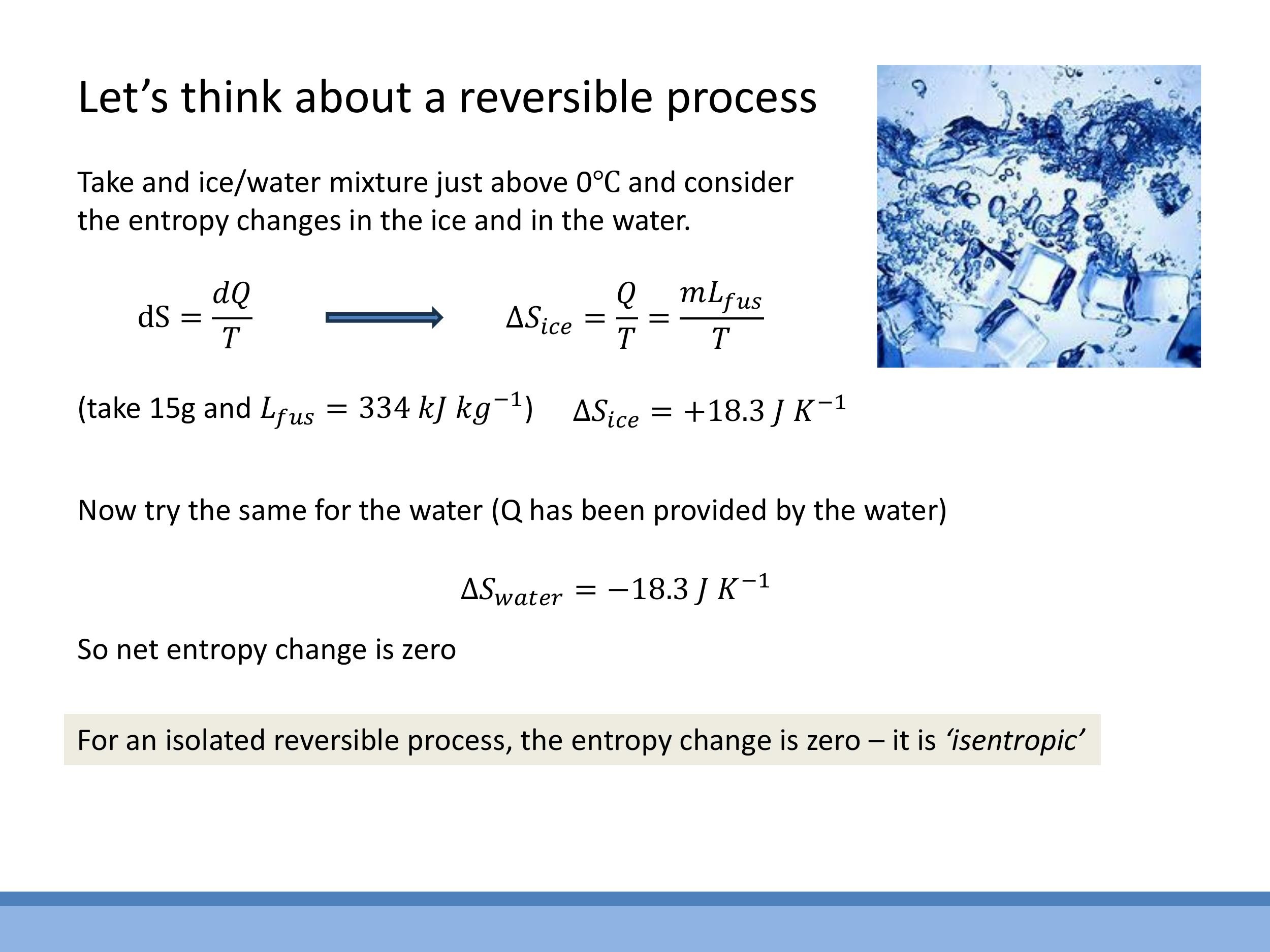

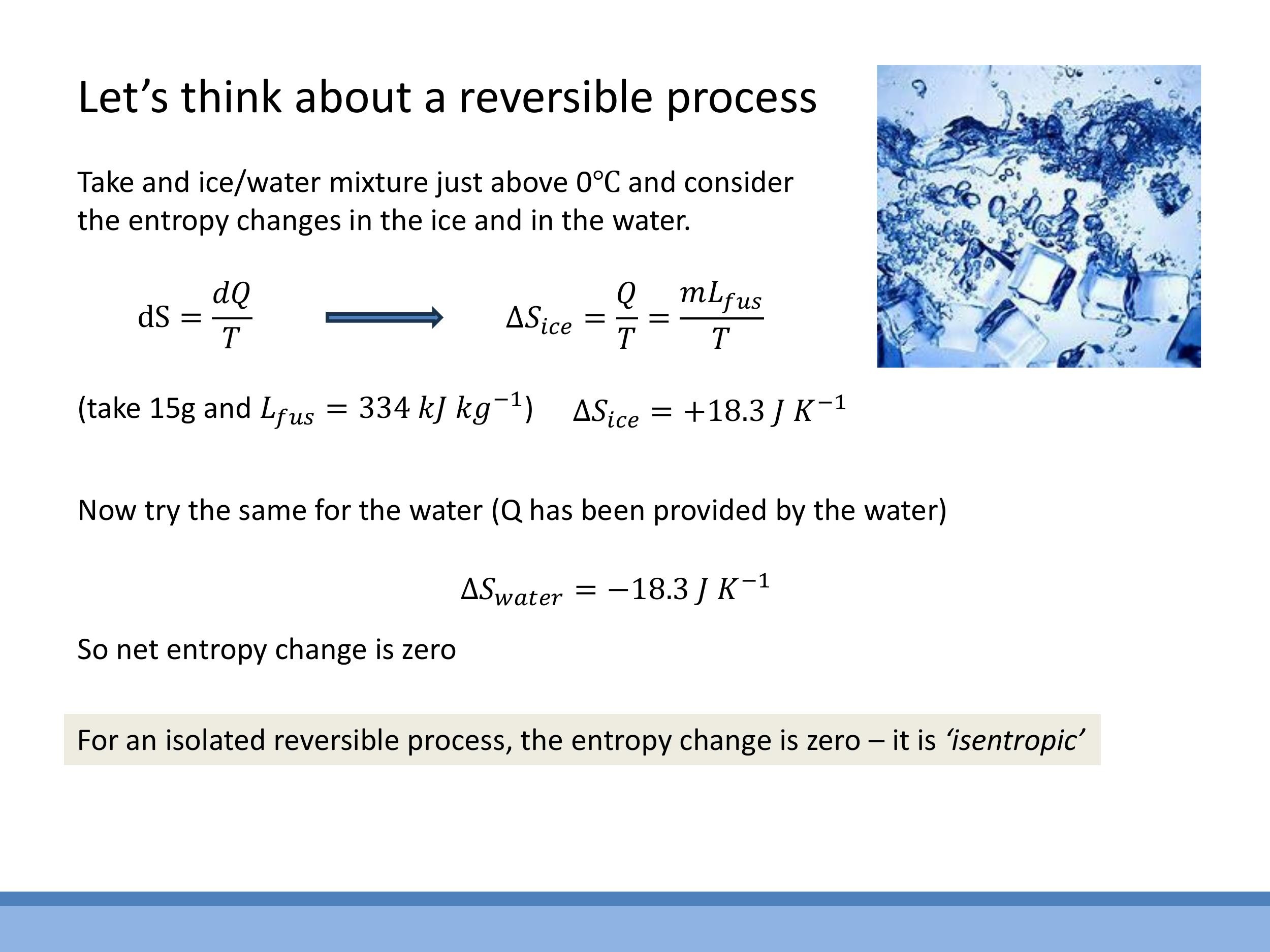

Consider the melting of a small amount of ice into water at $0 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ ($ 273.15 \, \text{K}$), an idealised reversible process.

For the ice, absorbing latent heat of fusion $L_{\text{fus}}$, the entropy change is $\Delta S_{\text{ice}} = \frac{m L_{\text{fus}}}{T}$. For $15 \, \text{g} $ of ice with $ L_{\text{fus}} = 334 \, \text{kJ kg}^{-1} $, $ \Delta S_{\text{ice}} = +18.3 \, \text{J K}^{-1} $. The water, which provides this heat, experiences an equal and opposite entropy change: $ \Delta S_{\text{water}} = -18.3 \, \text{J K}^{-1} $. In this isolated and reversible process, the total entropy change is zero ($ \Delta S_{\text{total}} = 0$), defining it as an isentropic process.

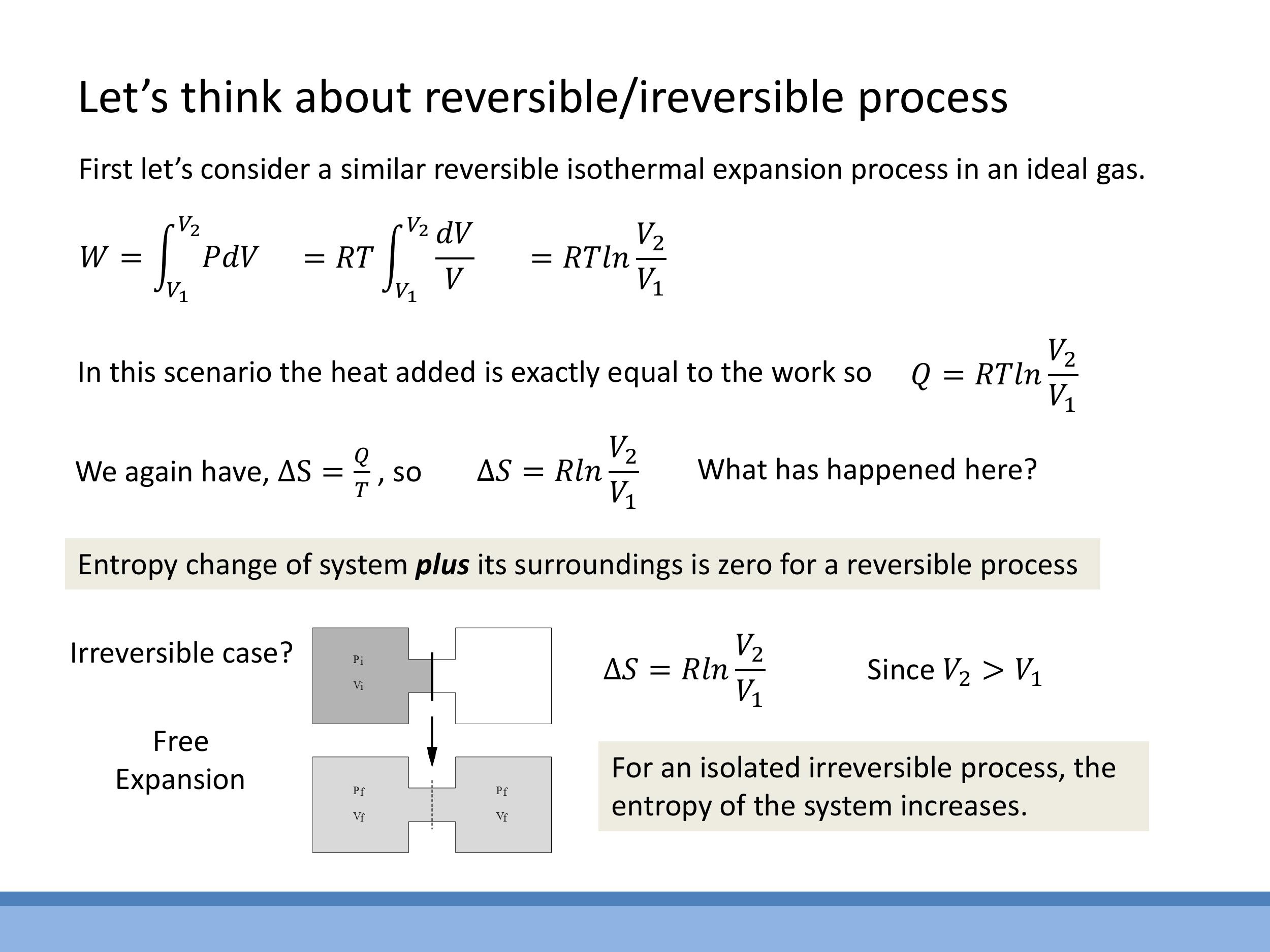

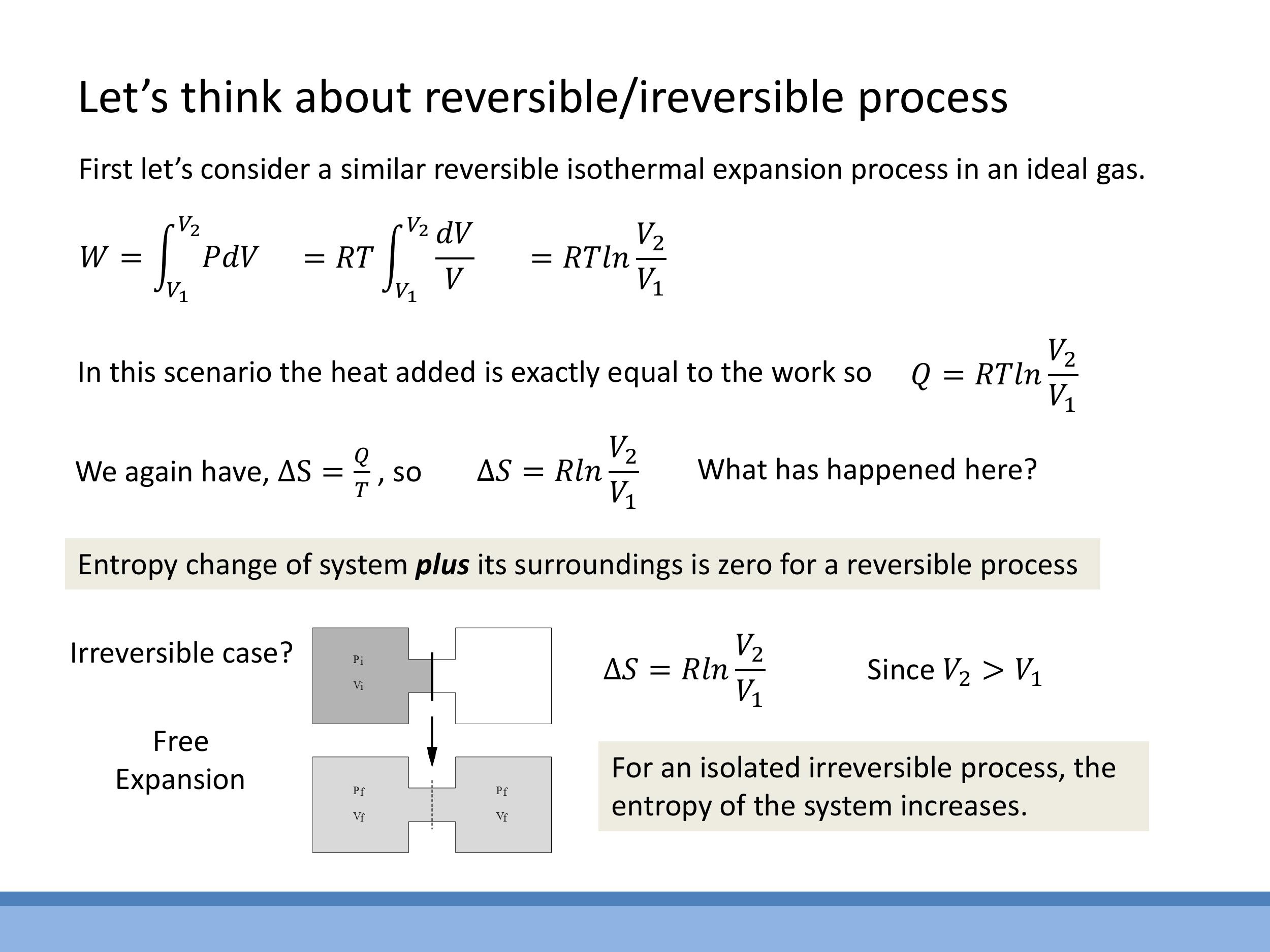

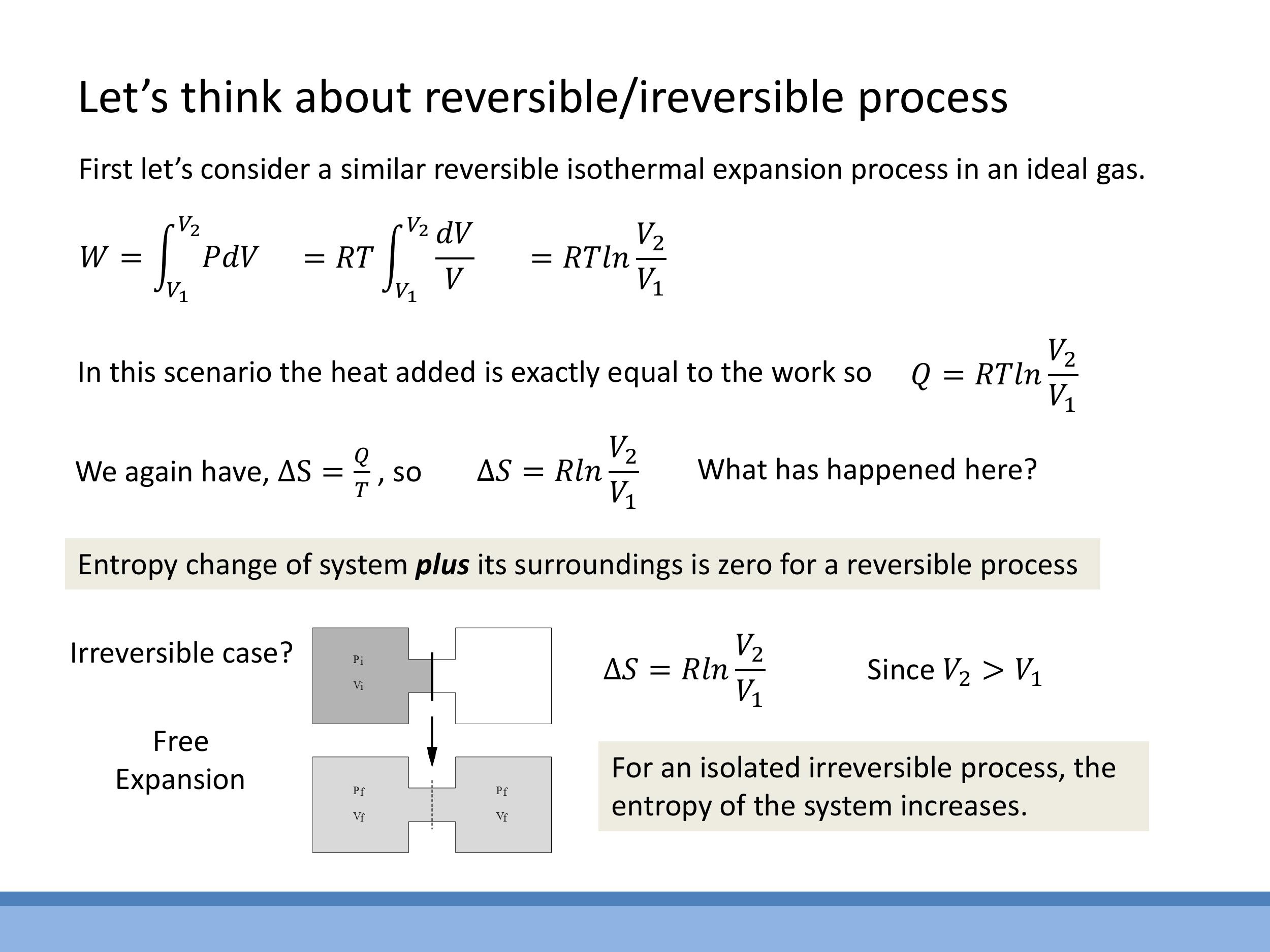

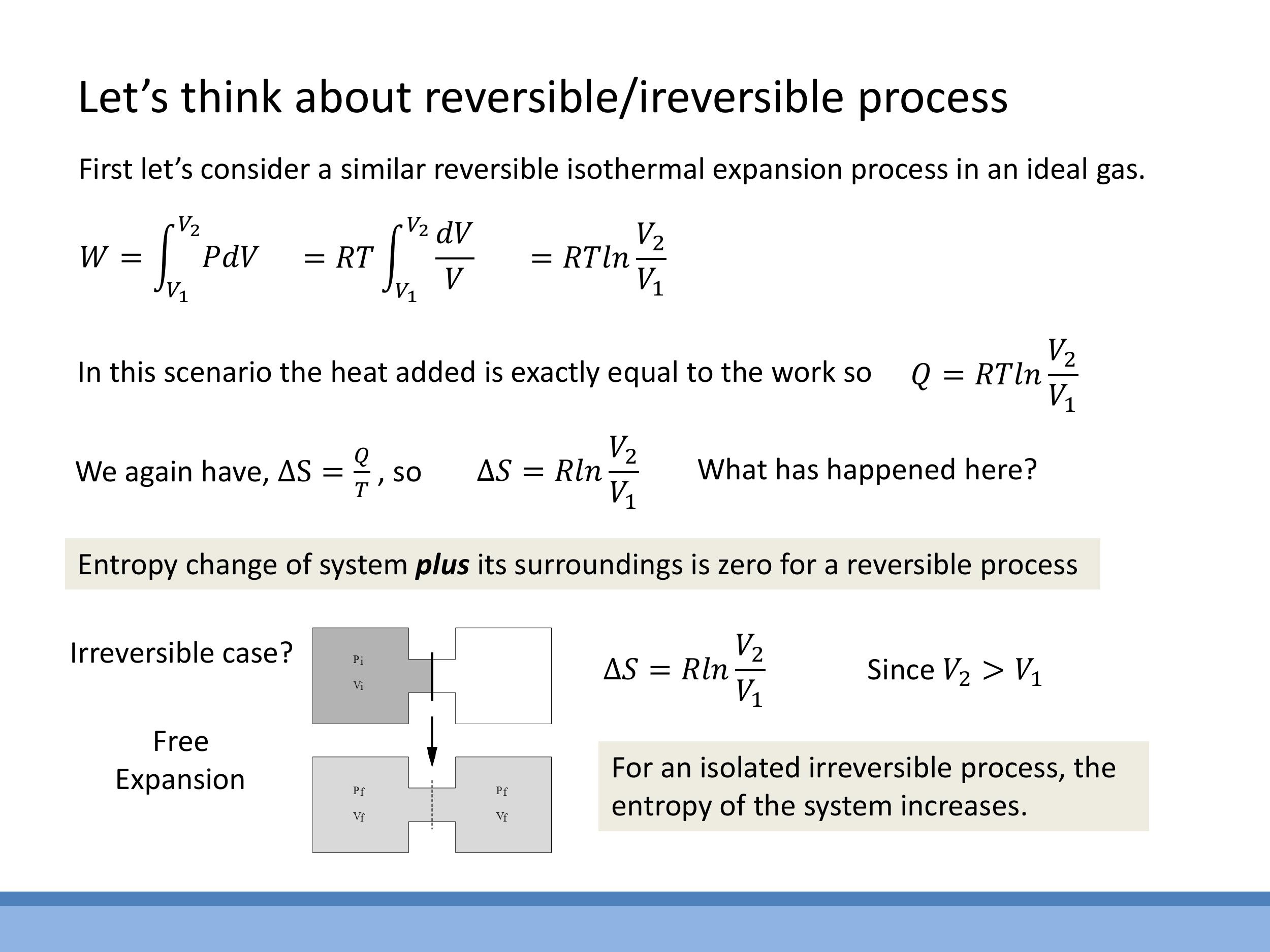

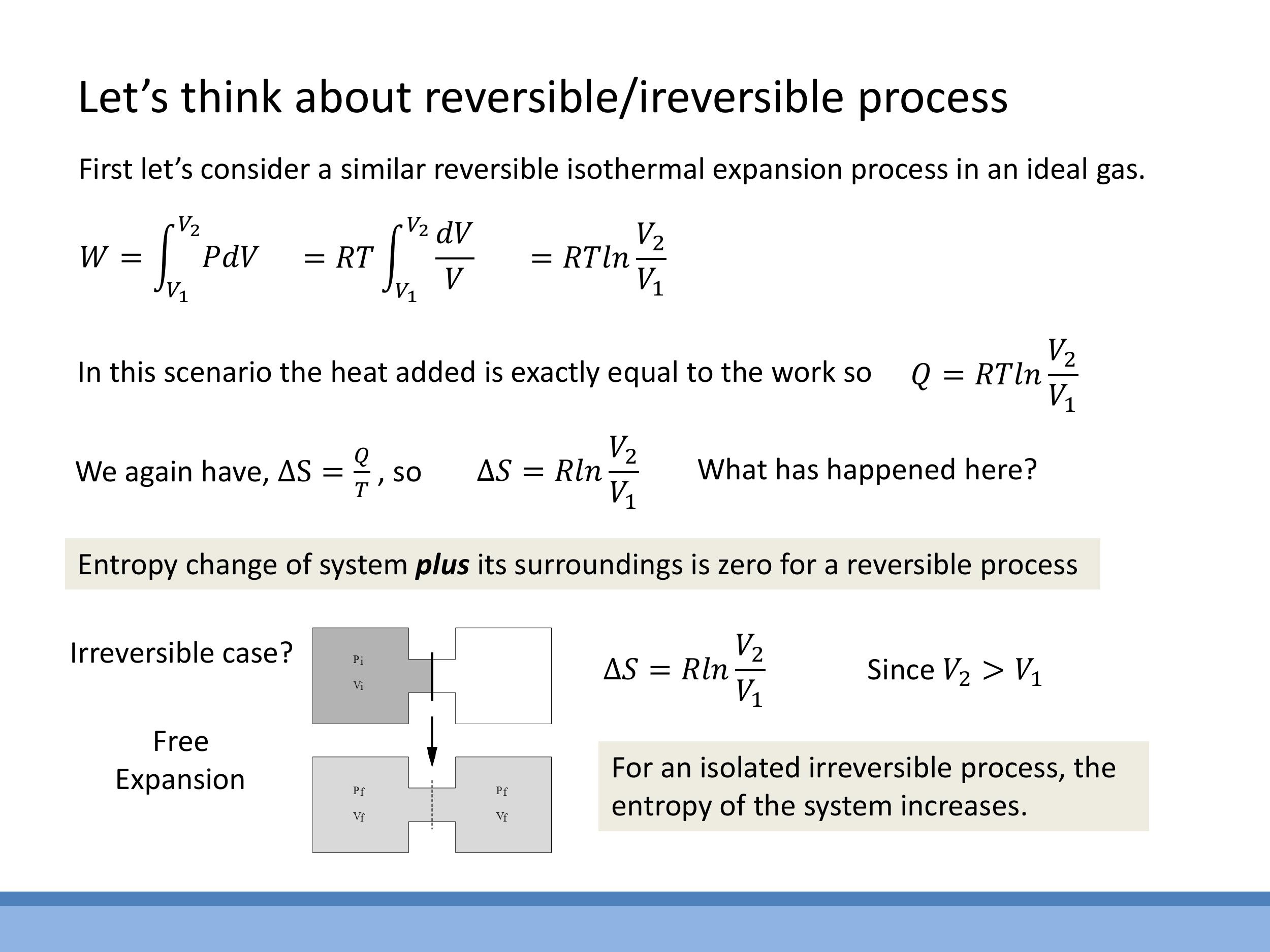

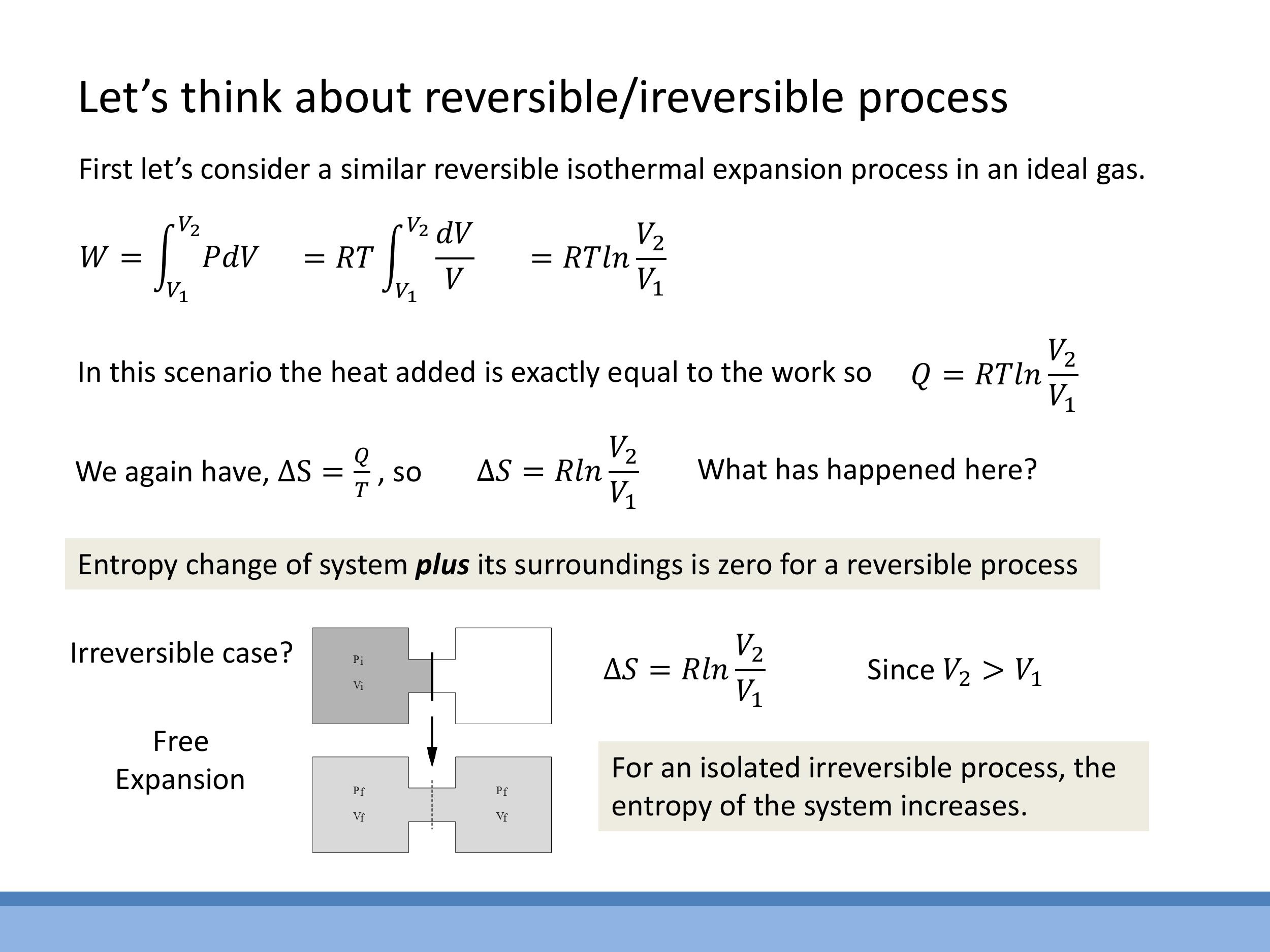

6.2 Reversible isothermal expansion of an ideal gas

For a reversible isothermal expansion of an ideal gas, the internal energy change is $\Delta U = 0$. Therefore, the heat absorbed $Q$ is equal to the work done by the gas $W$. The work done is $W = \int P \, \text{d}V = nRT \ln(V_2/V_1) $, so $ Q = nRT \ln(V_2/V_1)$.

The entropy change of the system is $\Delta S_{\text{sys}} = Q/T = nR \ln(V_2/V_1)$. If this process is perfectly reversible, the entropy change of the surroundings is $\Delta S_{\text{surr}} = -nR \ln(V_2/V_1)$, ensuring that the total entropy change of the universe remains zero ($\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = 0$).

6.3 Irreversible free expansion (isolated)

Consider an irreversible free expansion of an ideal gas into a vacuum. Since the system is isolated and expands against no external pressure, no heat is transferred ($Q=0$) and no work is done ($W=0$), leading to $\Delta U = 0$.

Even though the process itself is irreversible, entropy is a state function, meaning its change depends only on the initial and final states. The final state of a free expansion is the same as that of an isothermal expansion to the same volume. Therefore, the entropy change of the system is $\Delta S_{\text{sys}} = nR \ln(V_2/V_1)$. As the system is isolated, $\Delta S_{\text{surr}} = 0$, which means $\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = \Delta S_{\text{sys}} > 0$. This confirms that the entropy of an isolated, irreversible process always increases.

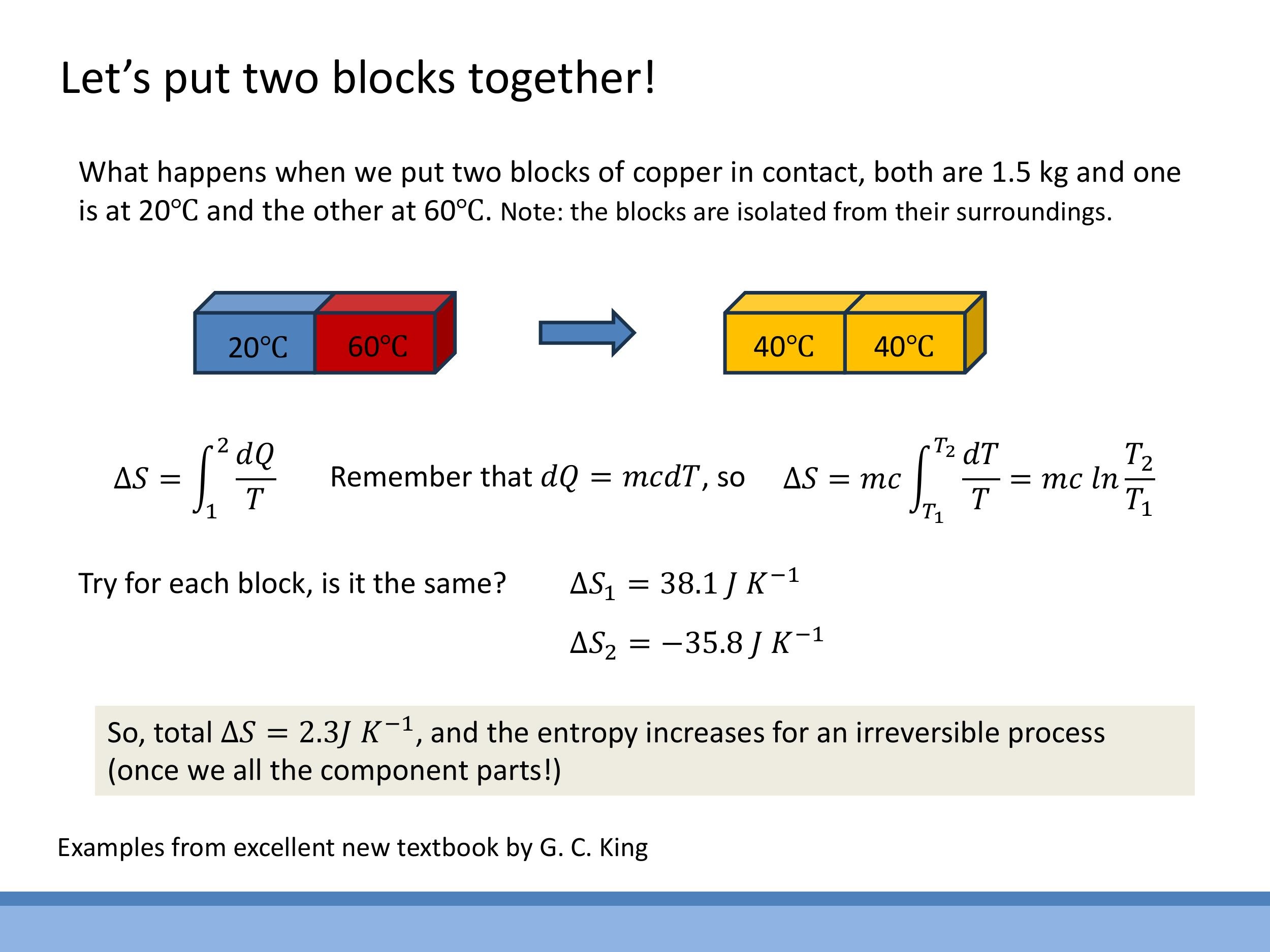

6.4 Two copper blocks reaching equilibrium (isolated, irreversible)

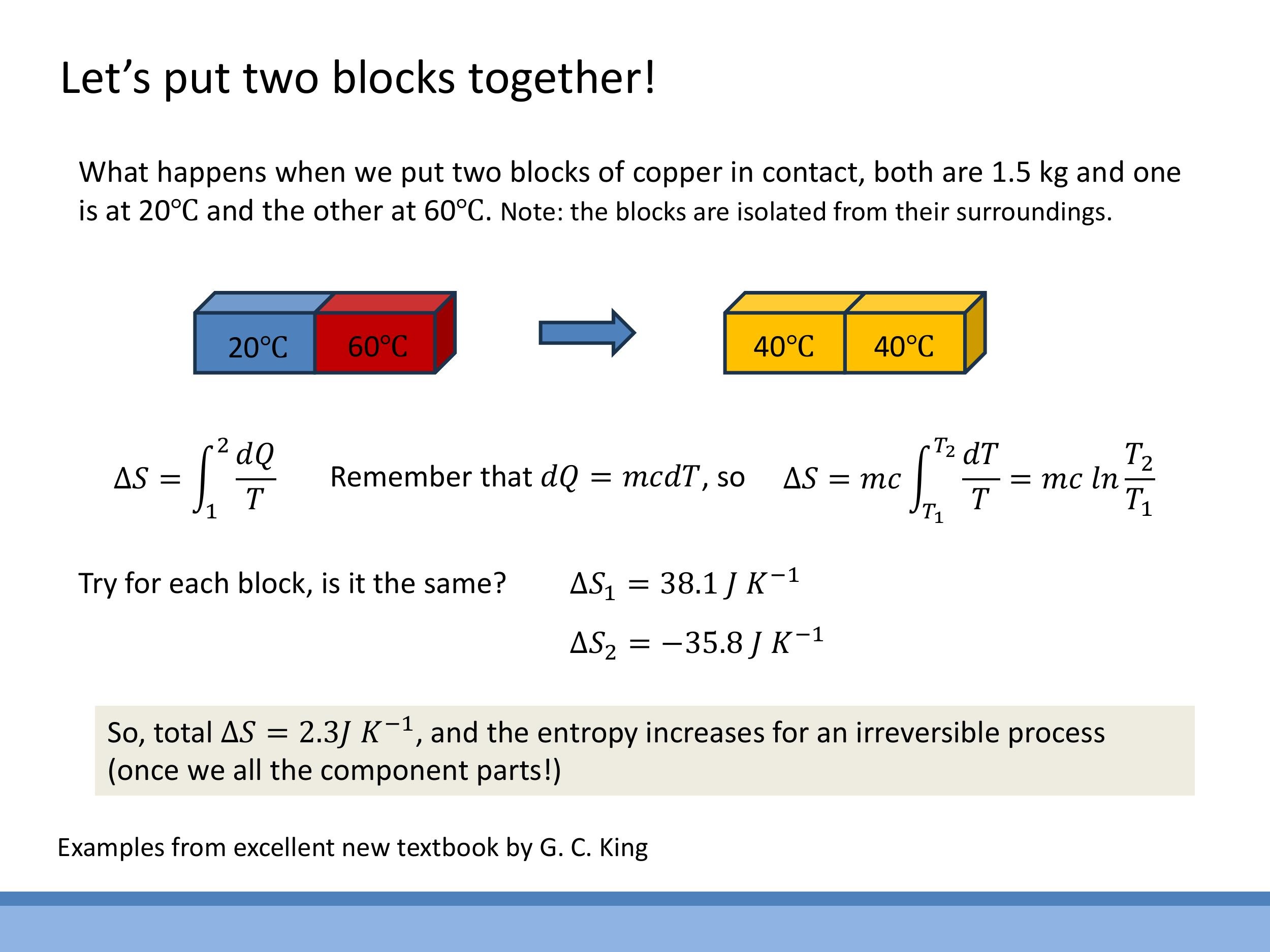

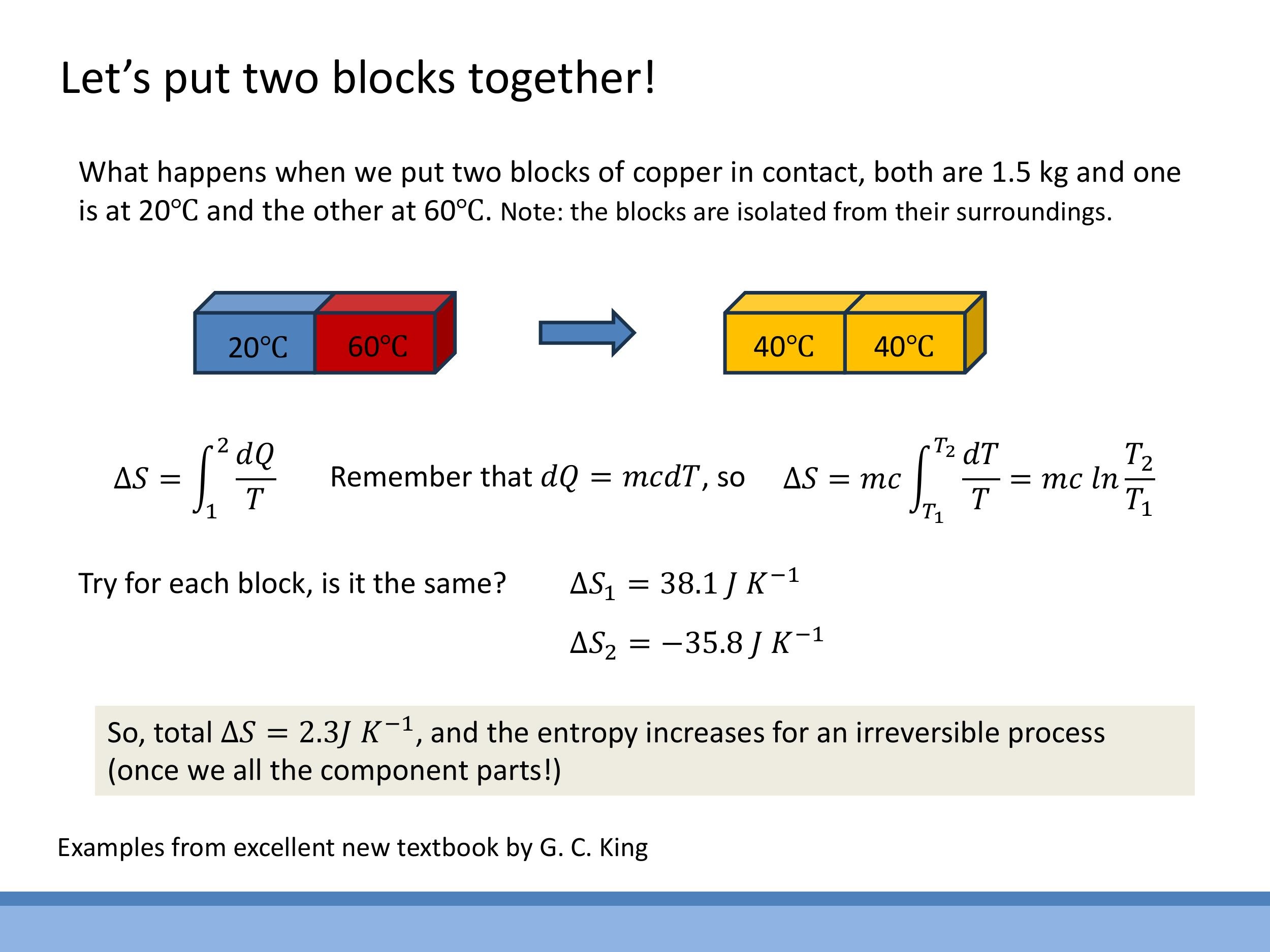

Consider two $1.5 \, \text{kg} $ copper blocks, initially at $ 20 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ ($ 293.15 \, \text{K} $) and $ 60 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ ($ 333.15 \, \text{K} $), placed in contact within an isolated system. They equilibrate at $ 40 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ ($ 313.15 \, \text{K}$).

The entropy change for each block can be calculated using $\Delta S = mc \ln(T_2/T_1)$, where $c$ is the specific heat capacity of copper. For the cold block, $\Delta S_{\text{cold}} = +38.1 \, \text{J K}^{-1} $. For the hot block, $ \Delta S_{\text{hot}} = -35.8 \, \text{J K}^{-1} $. The total entropy change of the isolated system is $ \Delta S_{\text{total}} = (+38.1 - 35.8) \, \text{J K}^{-1} = +2.3 \, \text{J K}^{-1} $. This positive total entropy change demonstrates that for an isolated, irreversible process, the entropy of the universe increases. The colder body experiences a larger magnitude of entropy change per unit of heat transferred due to the $ 1/T$ factor.

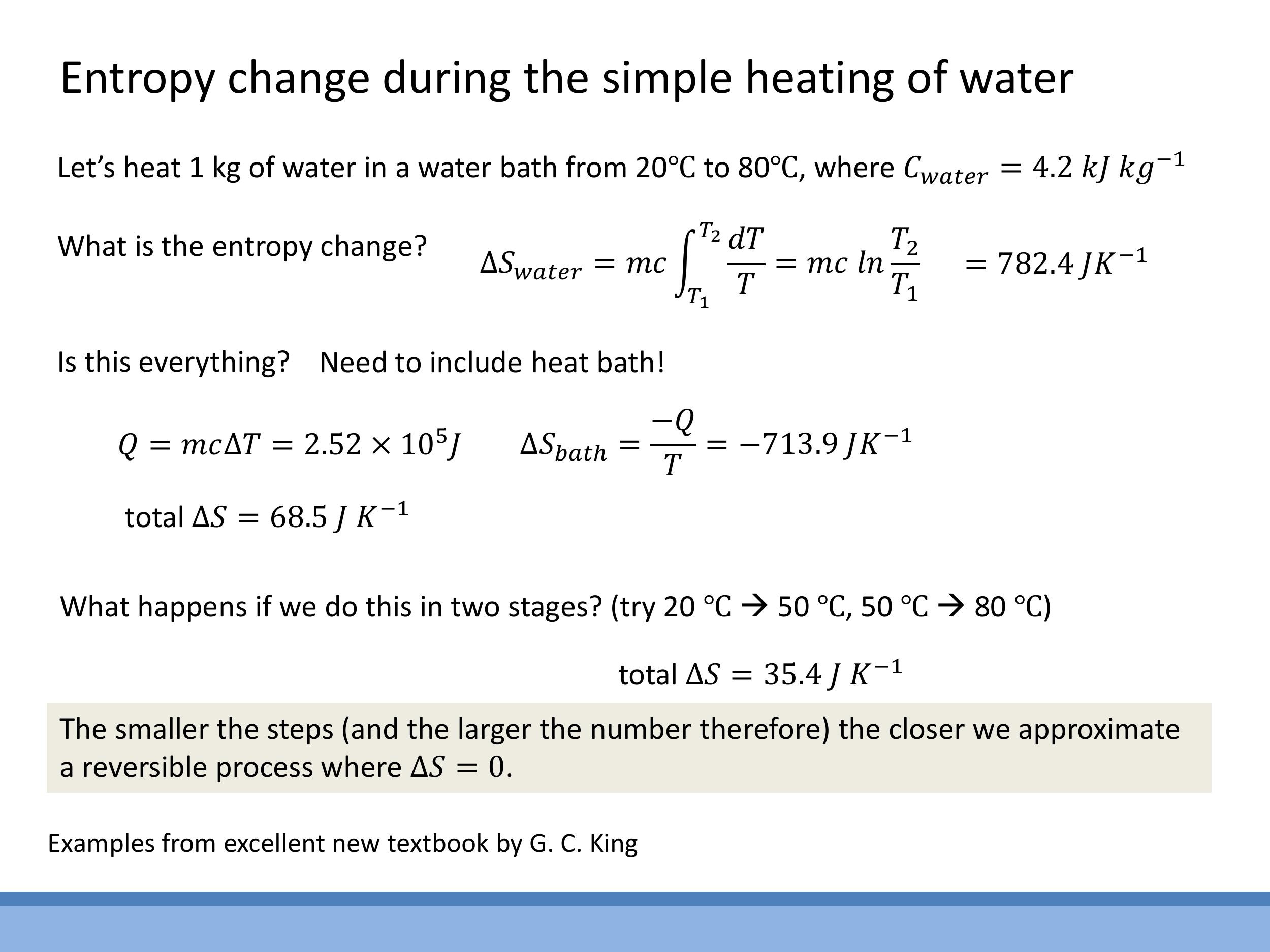

6.5 Heating water in a finite-temperature bath; many small steps reduce ΔS

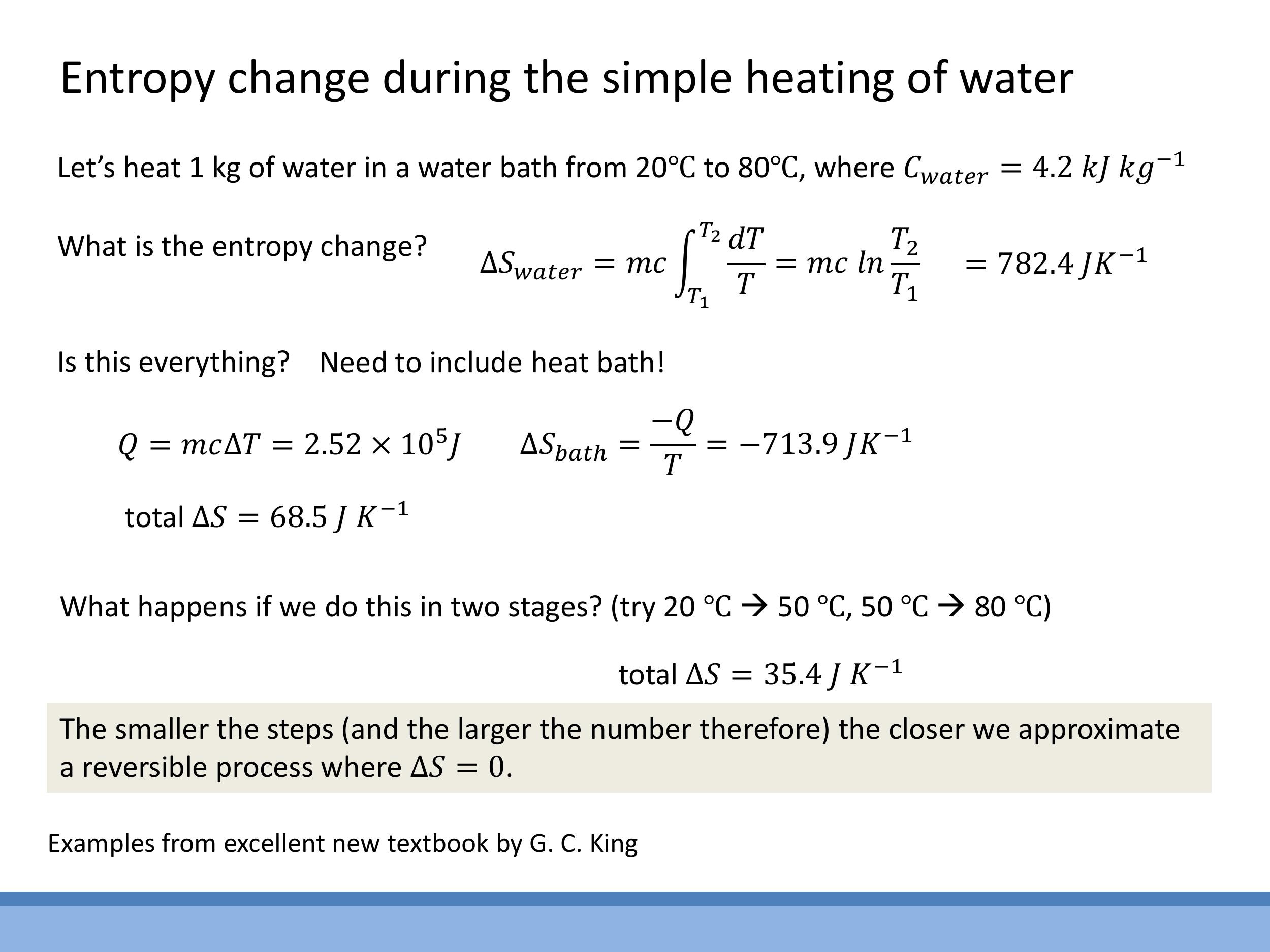

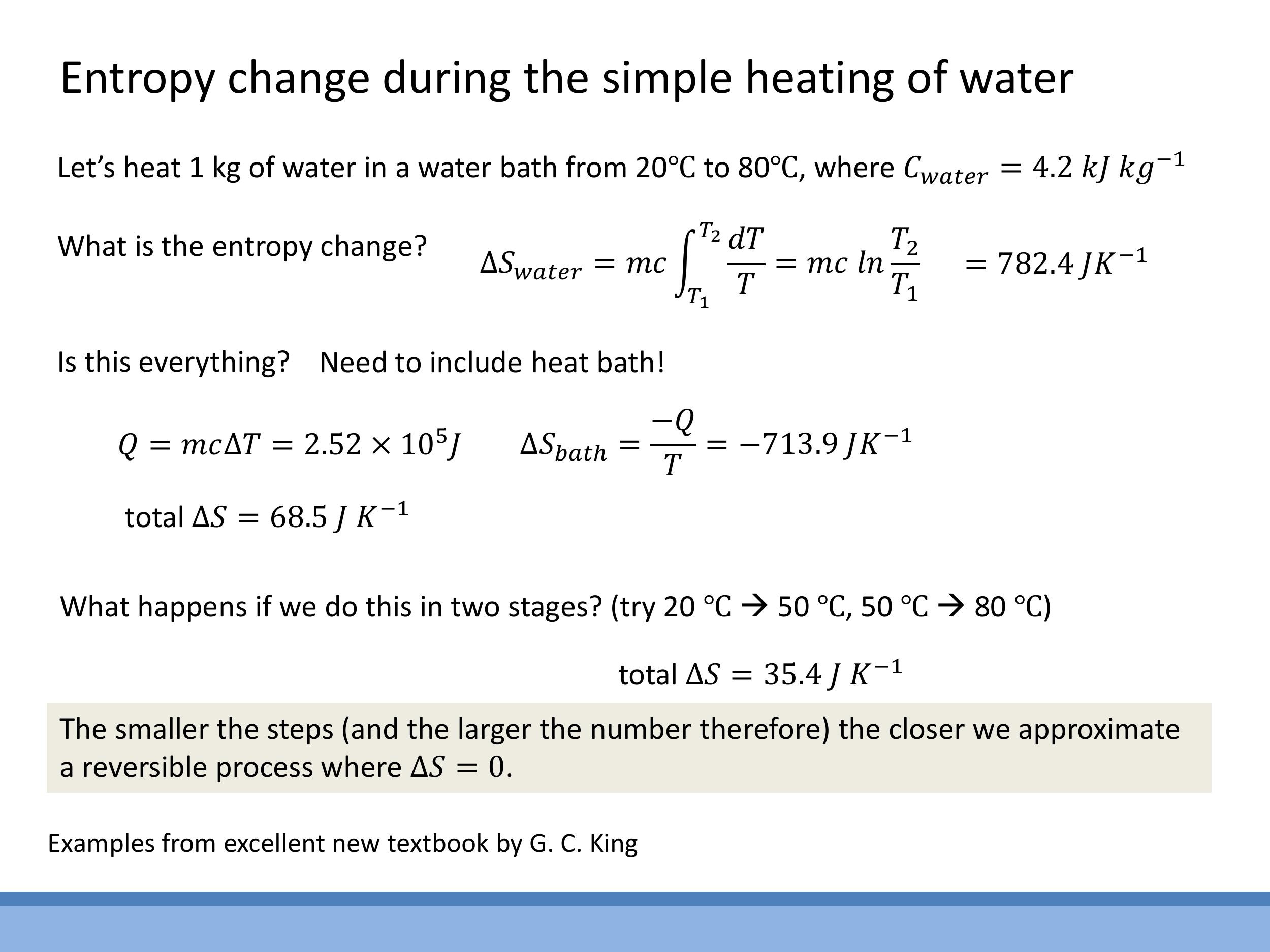

Consider heating $1 \, \text{kg} $ of water from $ 20 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ ($ 293.15 \, \text{K} $) to $ 80 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ ($ 353.15 \, \text{K} $) by placing it in a large heat bath at a constant $ 80 \, ^\circ\text{C}$.

The entropy change for the water (system) is $\Delta S_{\text{water}} = mc \ln(T_2/T_1) = +782.4 \, \text{J K}^{-1} $. The heat transferred from the bath is $ Q = mc\Delta T $. The entropy change of the heat bath (surroundings) is $ \Delta S_{\text{bath}} = -Q/T_{\text{bath}} = -713.9 \, \text{J K}^{-1} $. The total entropy change of the universe is $ \Delta S_{\text{universe}} = (+782.4 - 713.9) \, \text{J K}^{-1} = +68.5 \, \text{J K}^{-1}$.

If this heating process is carried out in two steps (e.g., from $20 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ to $ 50 \, ^\circ\text{C} $, then from $ 50 \, ^\circ\text{C} $ to $ 80 \, ^\circ\text{C} $), the total entropy change of the universe is reduced to $ +35.4 \, \text{J K}^{-1}$. This illustrates a key principle: performing a process in a greater number of smaller, quasi-static steps approximates a reversible process more closely. In the ideal limit of an infinite number of infinitesimal steps, the total entropy change of the universe approaches zero, characteristic of a reversible process.

7) Consolidation: diagnosing processes with entropy

When analysing thermodynamic processes, it is crucial to identify the process type (isothermal, adiabatic, isochoric, isobaric) and determine whether it is reversible or irreversible. The spontaneity and feasibility of a process are ultimately decided by the total entropy change of the universe, which includes both the system and its surroundings. For reversible processes, $\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = 0$. For irreversible (spontaneous) processes, $\Delta S_{\text{universe}} > 0$.

This entropic perspective clarifies why heat engines require a cold sink. While the working fluid in an engine cycle may return to its initial state (thus $\Delta S_{\text{system}} = 0$), the rejection of waste heat $Q_C$ to a cold reservoir at temperature $T_C$ ensures that the entropy of the surroundings increases. This increase in the surroundings' entropy is necessary to offset the ordered extraction of energy as work, allowing the overall entropy of the universe to increase or remain constant, thereby satisfying the Second Law and making the cyclic operation thermodynamically possible.

Appendix: Enthalpy and “free” energies (signposts only)

Side Note: This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

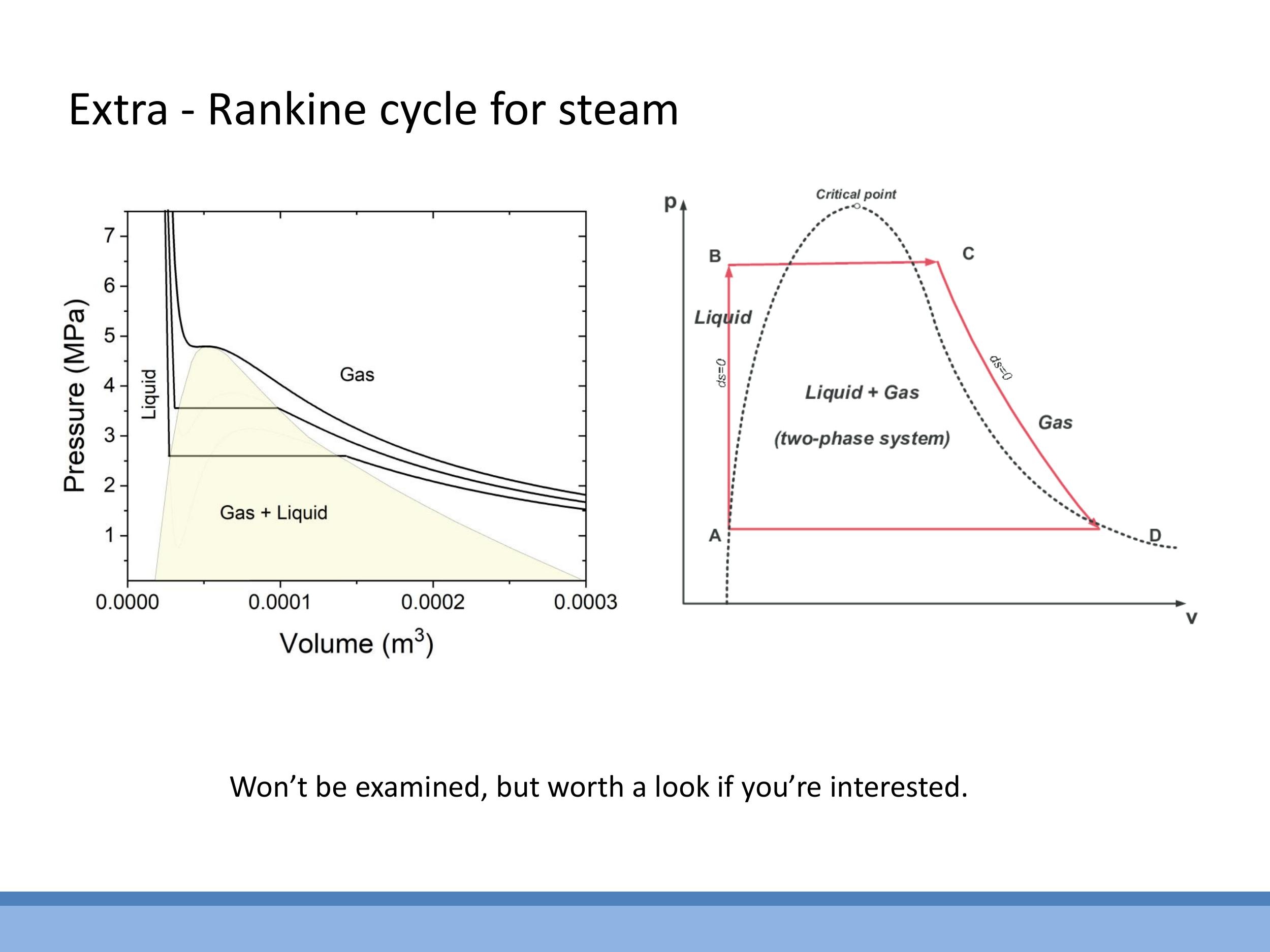

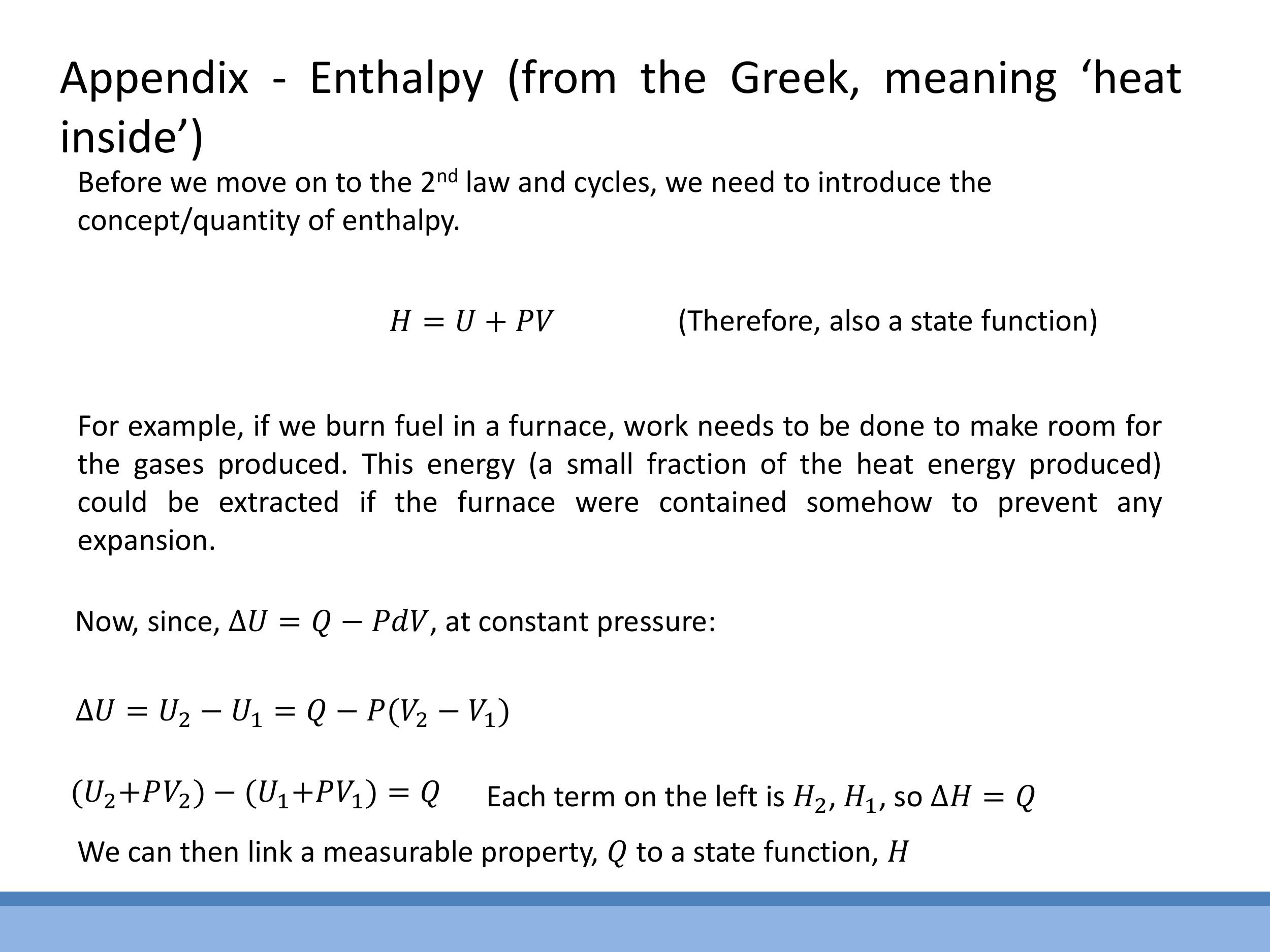

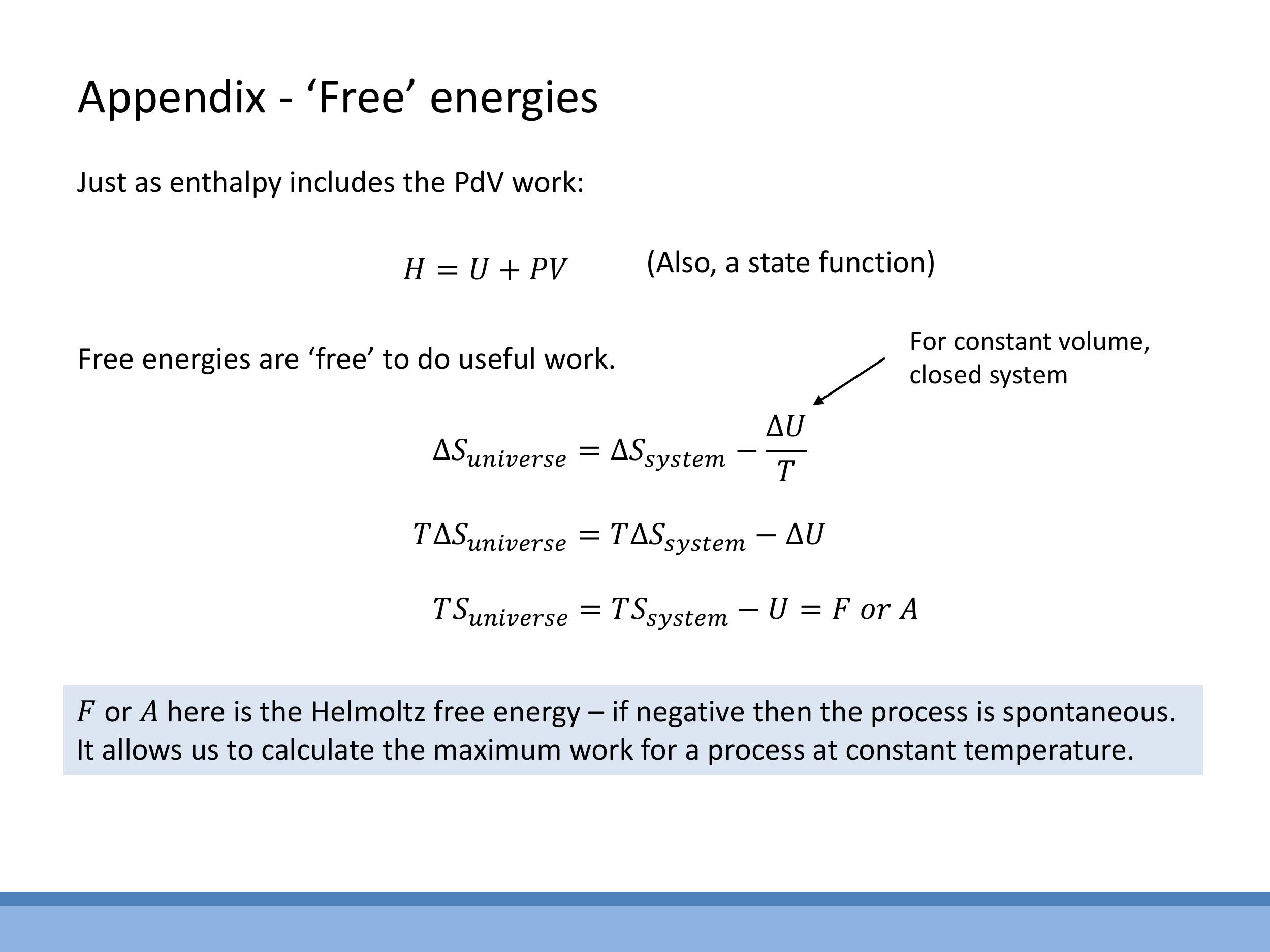

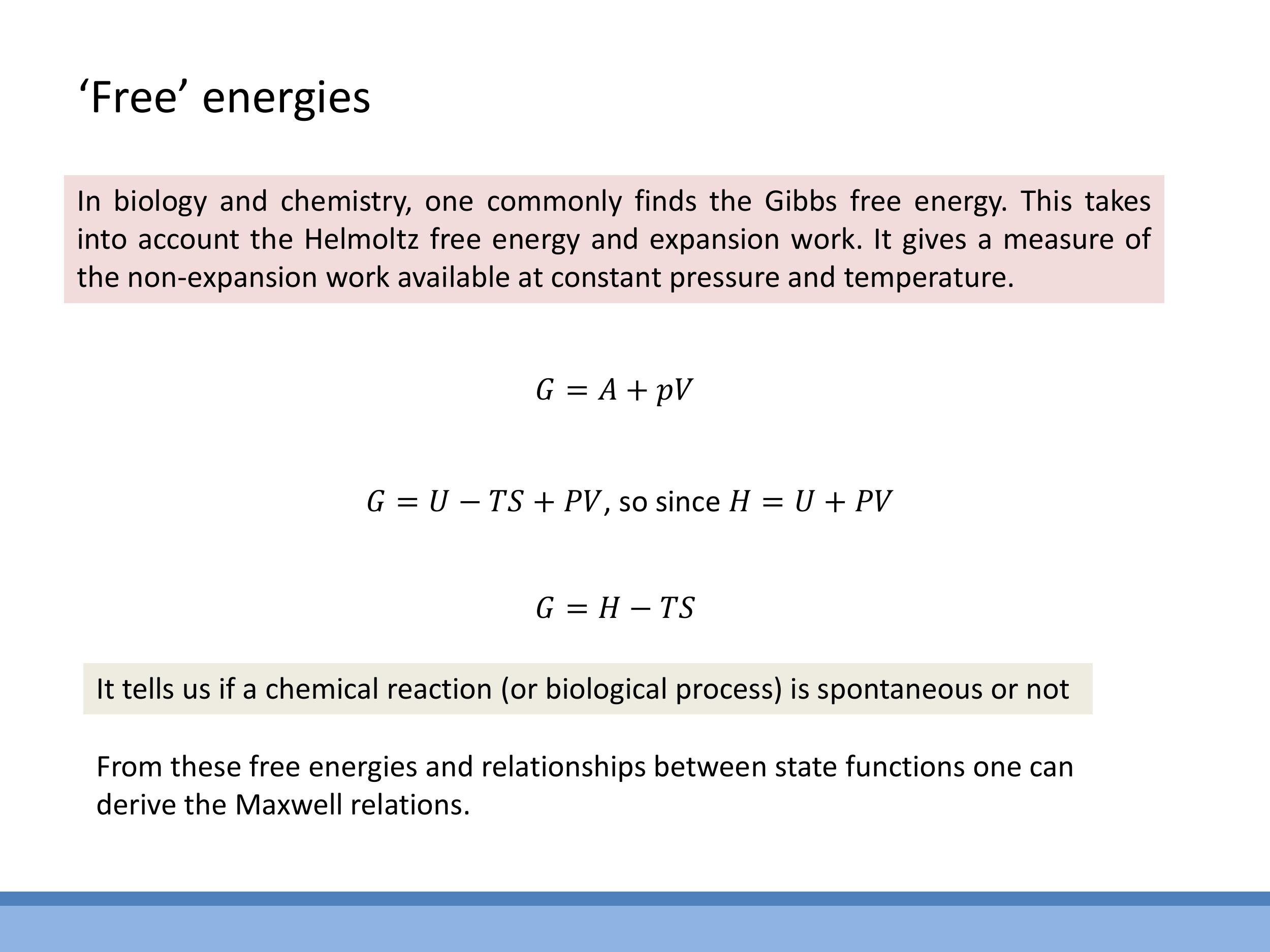

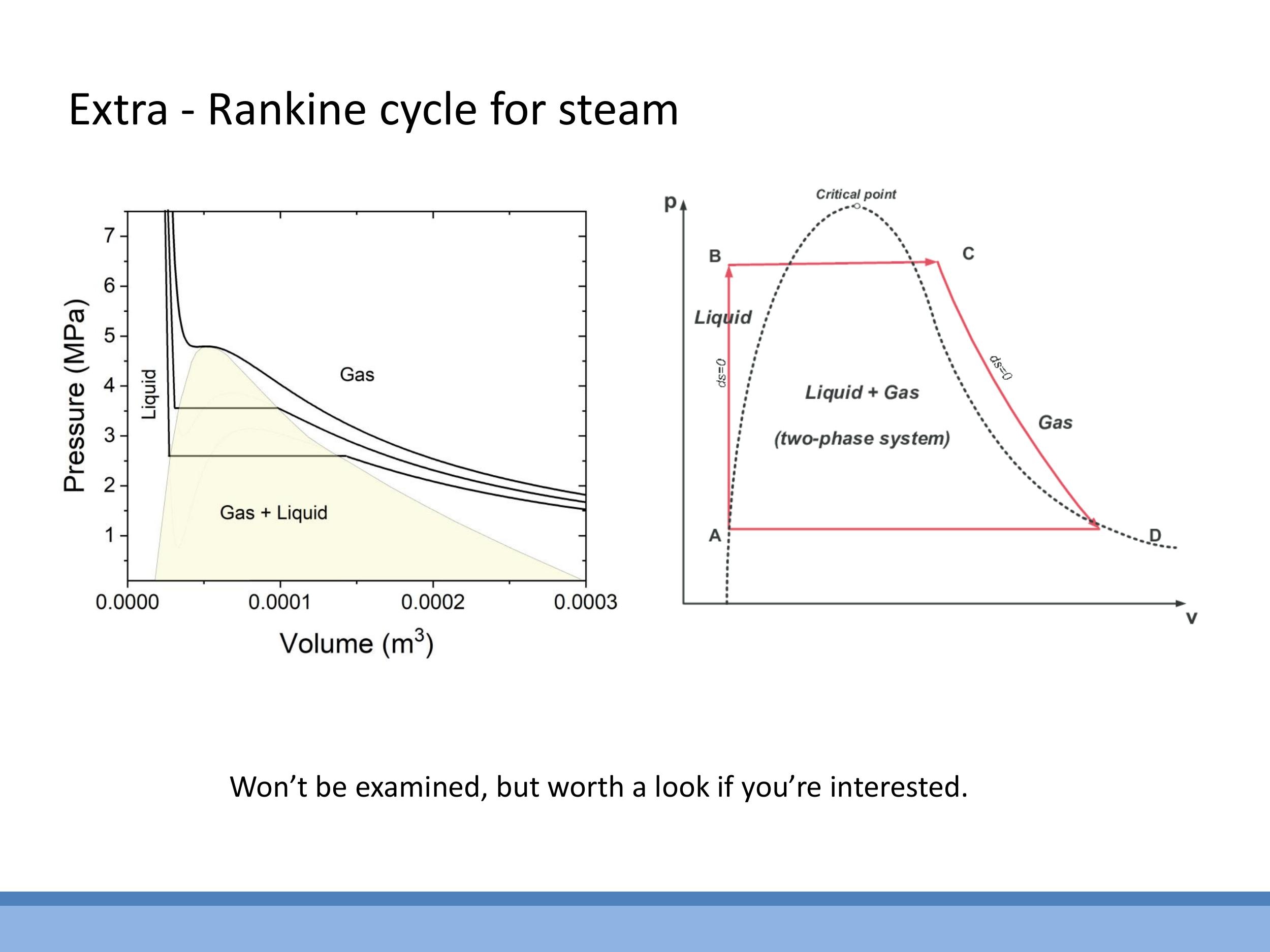

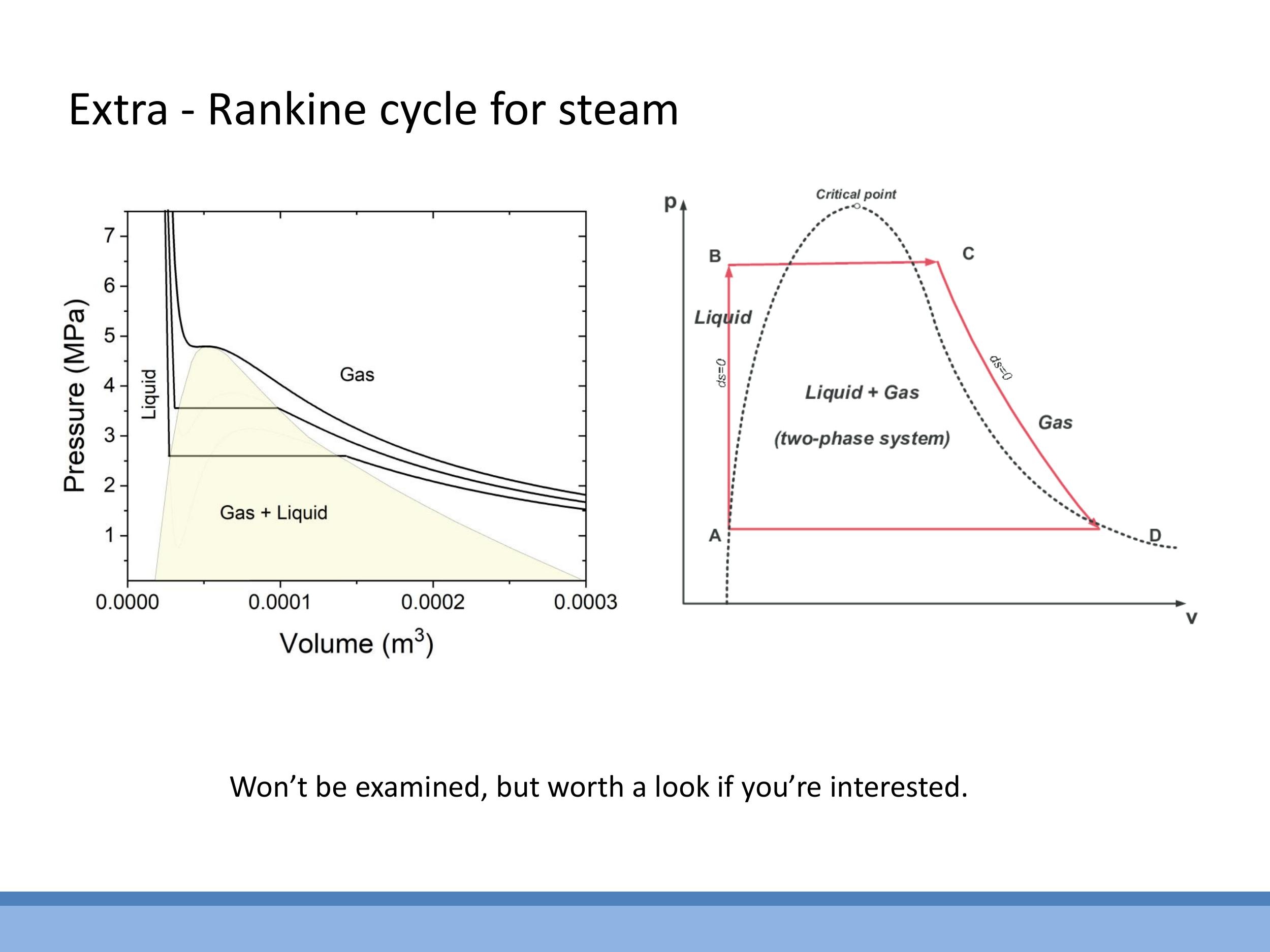

Enthalpy ($H$) is a state function defined as $H = U + PV$. It is particularly useful because at constant pressure, the change in enthalpy ($\Delta H$) is equal to the heat ($Q$) transferred to the system, directly linking a measurable quantity to a state function. The Helmholtz free energy ($F$ or $A$) is a state function that quantifies the maximum useful work available from a closed system at constant temperature and volume, with a negative $\Delta F$ indicating a spontaneous process under these conditions. The Gibbs free energy ($G$) is defined as $G = H - TS$. At constant temperature and pressure, $\Delta G$ determines the spontaneity of a process, making it highly relevant in chemistry and biology. The Rankine cycle, an additional example of a thermodynamic cycle for steam, is also mentioned as a concept that connects to real power plants, though it is not examinable in this course.

Key takeaways

A heat engine must operate in a cycle, and the Carnot cycle, comprising four reversible steps, serves as the theoretical benchmark with an efficiency of $\varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}} = 1 - T_C/T_H$, determined solely by the reservoir temperatures. The Second Law of Thermodynamics is expressed through two equivalent statements: the Kelvin statement, which asserts that no engine can entirely convert heat from a single hot source into work, thus requiring a cold sink; and the Clausius statement, which states that heat does not spontaneously flow from a colder to a hotter body. Entropy ($S$) quantifies energy dispersal or "quality," and thermodynamically, its change is defined as $\text{d}S = \text{d}Q_{\text{rev}}/T$. For spontaneous (irreversible) processes, the total entropy of the universe increases ($\Delta S_{\text{universe}} > 0$), while for reversible processes, it remains constant ($\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = 0$). The Carnot cycle, when plotted on a $T-S$ diagram, forms a rectangle, where the heat transferred ($Q_H = T_H \Delta S$ and $Q_C = T_C \Delta S$) is represented by the area under the isotherms, directly leading to the relationship $Q_C/Q_H = T_C/T_H$. Calculations of entropy changes in representative cases include: for a reversible isothermal ideal gas, $\Delta S_{\text{sys}} = nR \ln(V_2/V_1)$, with the surroundings balancing this change in a reversible process; for free expansion (an isolated, irreversible process), $\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = \Delta S_{\text{sys}} = nR \ln(V_2/V_1) > 0$; for thermal contact between bodies, $\Delta S$ is calculated as $mc \ln(T_2/T_1)$ for each body, noting that colder bodies experience a larger entropy gain per joule due to the $1/T$ factor; and finally, performing heating in many small steps towards equilibrium reduces $\Delta S_{\text{universe}}$, approaching the reversible limit.

## Lecture 12: Heat Engines and the Second Law (part 2)

### 0) Orientation, learning outcomes, and bridge from last time

This lecture builds upon the concepts introduced in "Heat Engines (part 1)", which covered thermodynamic cycles on P-V diagrams, the distinction between reversible and irreversible processes, and adiabats. Today's focus is on the formal statements of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, the introduction of entropy ($S$) as a new state function, the use of T-S diagrams, and practical calculations of entropy for various processes.

By the end of this lecture, students should be able to recall the Second Law and understand the equivalence between its Kelvin and Clausius statements. They will connect entropy to heat transfer and absolute temperature through the relationship $\text{d}S = \text{d}Q_{\text{rev}}/T$. Furthermore, students will learn to transform a Carnot cycle between P-V and T-S descriptions and calculate entropy changes in simple, representative processes, including both reversible and irreversible examples.

### 1) Useful work needs a cycle: the Carnot picture (quick recap)

For a system to perform repeated useful work, its working substance must undergo a cyclic process, returning to its initial state. The net work performed by such a cycle is represented by the area enclosed by the cycle's path on a P-V diagram.

The ideal Carnot cycle consists of four reversible steps. It begins with an isothermal expansion at a high temperature $T_H$, during which the system absorbs heat $Q_H$ and performs work, with no change in internal energy ($\Delta U = 0$, so $Q_H = W_{\text{by}}$). This is followed by an adiabatic expansion, where no heat is exchanged ($Q=0$), and the gas cools to a lower temperature $T_C$ while continuing to do work. The third step is an isothermal compression at $T_C$, during which heat $Q_C$ is rejected to a cold reservoir. Finally, an adiabatic compression returns the system to its initial state, with no heat exchange ($Q=0$), as work is done on the gas, raising its temperature back to $T_H$. The efficiency of a reversible Carnot engine is given by $\varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}} = 1 - T_C/T_H$, depending solely on the absolute temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs. The Stirling cycle, while using isochoric (constant volume) processes instead of adiabats, shares this same ideal efficiency when reversible and operating between the same two temperatures, $T_H$ and $T_C$.

### 2) Vocabulary refresh for processes

Thermodynamic processes are defined by which state variables remain constant or how heat transfer occurs. An **isothermal** process maintains a constant temperature ($T$). An **isochoric** process occurs at constant volume ($V$). An **isobaric** process maintains constant pressure ($P$). An **isentropic** process occurs at constant entropy ($S$). An **adiabatic** process is characterised by no heat transfer ($\text{d}Q = 0$).

### 3) The Second Law: Kelvin and Clausius statements and why they’re equivalent

The Second Law of Thermodynamics places fundamental limits on the conversion of heat into work and dictates the direction of spontaneous processes. It can be expressed through two equivalent statements.

The **Kelvin (Thomson) statement** asserts that no cyclic device can convert all the heat absorbed from a single hot source entirely into work; a cold sink is always necessary for a heat engine to operate. This means that 100% efficient heat engines are impossible. The **Clausius statement** declares that heat does not pass spontaneously from a colder body to a hotter body. To transfer heat "uphill" from a cold reservoir to a hot one (as in a refrigerator), external work must be performed on the system. These two statements are equivalent: if one were false, it would be possible to construct a device that violates the other. Thus, they represent two different facets of the same fundamental physical law.

### 4) Entropy S: what it measures and its definitions

Entropy ($S$) is a thermodynamic state function that quantifies the disorder or randomness of a system. Physically, it can be understood in several ways: as a measure of the disorder (e.g., a gas exhibits higher entropy than a liquid, which in turn has higher entropy than a solid); as a measure of how widely energy is distributed among accessible microstates of a system; or conversely, as an inverse measure of energy quality, where high-quality, concentrated energy is low-entropy, while dispersed "waste heat" is high-entropy.

The thermodynamic definition of a change in entropy is given by $\text{d}S = \text{d}Q_{\text{rev}} / T$, where $\text{d}Q_{\text{rev}}$ is the infinitesimal amount of heat transferred reversibly, and $T$ is the absolute temperature. This $1/T$ dependence implies that the same amount of heat transfer ($\text{d}Q$) causes a greater change in entropy ($\text{d}S$) in a colder system (low $T$) than in a hotter system (high $T$), similar to how a sneeze causes a larger disturbance in a quiet library than on a busy street. For context, the statistical definition of entropy, $S = k \ln W$ (Boltzmann's equation), relates entropy to the natural logarithm of the number of accessible microstates ($W$) where $k$ is Boltzmann's constant, but this is not used for calculations in this course.

### 5) The Carnot cycle on a T-S diagram and a simpler route to ε

The Carnot cycle, when depicted on a Temperature-Entropy ($T-S$) diagram, provides a simplified visual and algebraic representation compared to a P-V diagram.

On a $T-S$ diagram, the four reversible steps of the Carnot cycle form a perfect rectangle. The isothermal legs appear as horizontal lines: at $T_H$ for expansion (entropy increases from $S_1$ to $S_2$) and at $T_C$ for compression (entropy decreases from $S_2$ to $S_1$). The adiabatic, reversible legs are vertical lines, as $\text{d}Q = 0$ implies $\text{d}S = 0$, connecting the two isothermal temperatures $T_H$ and $T_C$.

In this representation, the heat transferred during an isothermal process is simply the area under the corresponding horizontal line. Thus, the heat absorbed from the hot reservoir is $Q_H = T_H \Delta S$, and the heat rejected to the cold reservoir is $Q_C = T_C \Delta S$, where $\Delta S = S_2 - S_1$. This directly leads to the ratio $Q_C/Q_H = T_C/T_H$, which, when substituted into the general efficiency formula, yields the Carnot efficiency $\varepsilon = 1 - T_C/T_H$. This graphical representation on a $T-S$ diagram significantly compresses the algebra, making the derivation of the Carnot efficiency immediate and intuitive, while still describing the same underlying physics as the P-V diagram.

### 6) Calculating entropy changes: representative worked cases

#### 6.1 Reversible phase change at fixed T: melting ice at 0 °C

Consider the melting of a small amount of ice into water at $0\,^\circ\text{C}$ ($273.15\,\text{K}$), an idealised reversible process.

For the ice, absorbing latent heat of fusion $L_{\text{fus}}$, the entropy change is $\Delta S_{\text{ice}} = \frac{m L_{\text{fus}}}{T}$. For $15\,\text{g}$ of ice with $L_{\text{fus}} = 334\,\text{kJ kg}^{-1}$, $\Delta S_{\text{ice}} = +18.3\,\text{J K}^{-1}$. The water, which provides this heat, experiences an equal and opposite entropy change: $\Delta S_{\text{water}} = -18.3\,\text{J K}^{-1}$. In this isolated and reversible process, the total entropy change is zero ($\Delta S_{\text{total}} = 0$), defining it as an isentropic process.

#### 6.2 Reversible isothermal expansion of an ideal gas

For a reversible isothermal expansion of an ideal gas, the internal energy change is $\Delta U = 0$. Therefore, the heat absorbed $Q$ is equal to the work done by the gas $W$. The work done is $W = \int P\,\text{d}V = nRT \ln(V_2/V_1)$, so $Q = nRT \ln(V_2/V_1)$.

The entropy change of the system is $\Delta S_{\text{sys}} = Q/T = nR \ln(V_2/V_1)$. If this process is perfectly reversible, the entropy change of the surroundings is $\Delta S_{\text{surr}} = -nR \ln(V_2/V_1)$, ensuring that the total entropy change of the universe remains zero ($\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = 0$).

#### 6.3 Irreversible free expansion (isolated)

Consider an irreversible free expansion of an ideal gas into a vacuum. Since the system is isolated and expands against no external pressure, no heat is transferred ($Q=0$) and no work is done ($W=0$), leading to $\Delta U = 0$.

Even though the process itself is irreversible, entropy is a state function, meaning its change depends only on the initial and final states. The final state of a free expansion is the same as that of an isothermal expansion to the same volume. Therefore, the entropy change of the system is $\Delta S_{\text{sys}} = nR \ln(V_2/V_1)$. As the system is isolated, $\Delta S_{\text{surr}} = 0$, which means $\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = \Delta S_{\text{sys}} > 0$. This confirms that the entropy of an isolated, irreversible process always increases.

#### 6.4 Two copper blocks reaching equilibrium (isolated, irreversible)

Consider two $1.5\,\text{kg}$ copper blocks, initially at $20\,^\circ\text{C}$ ($293.15\,\text{K}$) and $60\,^\circ\text{C}$ ($333.15\,\text{K}$), placed in contact within an isolated system. They equilibrate at $40\,^\circ\text{C}$ ($313.15\,\text{K}$).

The entropy change for each block can be calculated using $\Delta S = mc \ln(T_2/T_1)$, where $c$ is the specific heat capacity of copper. For the cold block, $\Delta S_{\text{cold}} = +38.1\,\text{J K}^{-1}$. For the hot block, $\Delta S_{\text{hot}} = -35.8\,\text{J K}^{-1}$. The total entropy change of the isolated system is $\Delta S_{\text{total}} = (+38.1 - 35.8)\,\text{J K}^{-1} = +2.3\,\text{J K}^{-1}$. This positive total entropy change demonstrates that for an isolated, irreversible process, the entropy of the universe increases. The colder body experiences a larger magnitude of entropy change per unit of heat transferred due to the $1/T$ factor.

#### 6.5 Heating water in a finite-temperature bath; many small steps reduce ΔS

Consider heating $1\,\text{kg}$ of water from $20\,^\circ\text{C}$ ($293.15\,\text{K}$) to $80\,^\circ\text{C}$ ($353.15\,\text{K}$) by placing it in a large heat bath at a constant $80\,^\circ\text{C}$.

The entropy change for the water (system) is $\Delta S_{\text{water}} = mc \ln(T_2/T_1) = +782.4\,\text{J K}^{-1}$. The heat transferred from the bath is $Q = mc\Delta T$. The entropy change of the heat bath (surroundings) is $\Delta S_{\text{bath}} = -Q/T_{\text{bath}} = -713.9\,\text{J K}^{-1}$. The total entropy change of the universe is $\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = (+782.4 - 713.9)\,\text{J K}^{-1} = +68.5\,\text{J K}^{-1}$.

If this heating process is carried out in two steps (e.g., from $20\,^\circ\text{C}$ to $50\,^\circ\text{C}$, then from $50\,^\circ\text{C}$ to $80\,^\circ\text{C}$), the total entropy change of the universe is reduced to $+35.4\,\text{J K}^{-1}$. This illustrates a key principle: performing a process in a greater number of smaller, quasi-static steps approximates a reversible process more closely. In the ideal limit of an infinite number of infinitesimal steps, the total entropy change of the universe approaches zero, characteristic of a reversible process.

### 7) Consolidation: diagnosing processes with entropy

When analysing thermodynamic processes, it is crucial to identify the process type (isothermal, adiabatic, isochoric, isobaric) and determine whether it is reversible or irreversible. The spontaneity and feasibility of a process are ultimately decided by the total entropy change of the universe, which includes both the system and its surroundings. For reversible processes, $\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = 0$. For irreversible (spontaneous) processes, $\Delta S_{\text{universe}} > 0$.

This entropic perspective clarifies why heat engines require a cold sink. While the working fluid in an engine cycle may return to its initial state (thus $\Delta S_{\text{system}} = 0$), the rejection of waste heat $Q_C$ to a cold reservoir at temperature $T_C$ ensures that the entropy of the surroundings increases. This increase in the surroundings' entropy is necessary to offset the ordered extraction of energy as work, allowing the overall entropy of the universe to increase or remain constant, thereby satisfying the Second Law and making the cyclic operation thermodynamically possible.

## Appendix: Enthalpy and “free” energies (signposts only)

*Side Note:* This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

**Enthalpy** ($H$) is a state function defined as $H = U + PV$. It is particularly useful because at constant pressure, the change in enthalpy ($\Delta H$) is equal to the heat ($Q$) transferred to the system, directly linking a measurable quantity to a state function. The **Helmholtz free energy** ($F$ or $A$) is a state function that quantifies the maximum useful work available from a closed system at constant temperature and volume, with a negative $\Delta F$ indicating a spontaneous process under these conditions. The **Gibbs free energy** ($G$) is defined as $G = H - TS$. At constant temperature and pressure, $\Delta G$ determines the spontaneity of a process, making it highly relevant in chemistry and biology. The Rankine cycle, an additional example of a thermodynamic cycle for steam, is also mentioned as a concept that connects to real power plants, though it is not examinable in this course.

## Key takeaways

A heat engine must operate in a cycle, and the Carnot cycle, comprising four reversible steps, serves as the theoretical benchmark with an efficiency of $\varepsilon_{\text{Carnot}} = 1 - T_C/T_H$, determined solely by the reservoir temperatures. The Second Law of Thermodynamics is expressed through two equivalent statements: the Kelvin statement, which asserts that no engine can entirely convert heat from a single hot source into work, thus requiring a cold sink; and the Clausius statement, which states that heat does not spontaneously flow from a colder to a hotter body. Entropy ($S$) quantifies energy dispersal or "quality," and thermodynamically, its change is defined as $\text{d}S = \text{d}Q_{\text{rev}}/T$. For spontaneous (irreversible) processes, the total entropy of the universe increases ($\Delta S_{\text{universe}} > 0$), while for reversible processes, it remains constant ($\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = 0$). The Carnot cycle, when plotted on a $T-S$ diagram, forms a rectangle, where the heat transferred ($Q_H = T_H \Delta S$ and $Q_C = T_C \Delta S$) is represented by the area under the isotherms, directly leading to the relationship $Q_C/Q_H = T_C/T_H$. Calculations of entropy changes in representative cases include: for a reversible isothermal ideal gas, $\Delta S_{\text{sys}} = nR \ln(V_2/V_1)$, with the surroundings balancing this change in a reversible process; for free expansion (an isolated, irreversible process), $\Delta S_{\text{universe}} = \Delta S_{\text{sys}} = nR \ln(V_2/V_1) > 0$; for thermal contact between bodies, $\Delta S$ is calculated as $mc \ln(T_2/T_1)$ for each body, noting that colder bodies experience a larger entropy gain per joule due to the $1/T$ factor; and finally, performing heating in many small steps towards equilibrium reduces $\Delta S_{\text{universe}}$, approaching the reversible limit.