Lecture 13: Liquids - structure, surface tension, and capillarity

The course now shifts focus from classical thermodynamics to the properties of specific states of matter, beginning with liquids. The previous block of lectures covered thermodynamic cycles, including the Carnot and Stirling cycles, and introduced fundamental concepts like entropy and the Second Law. These tools for understanding energy and temperature will continue to be relevant. Today's lecture will build a structural picture of liquids, define macroscopic surface tension and link it to microscopic bond energy, and then explore capillary action with simple quantitative models.

# 1) What is a liquid? Macroscopic properties and energy balance

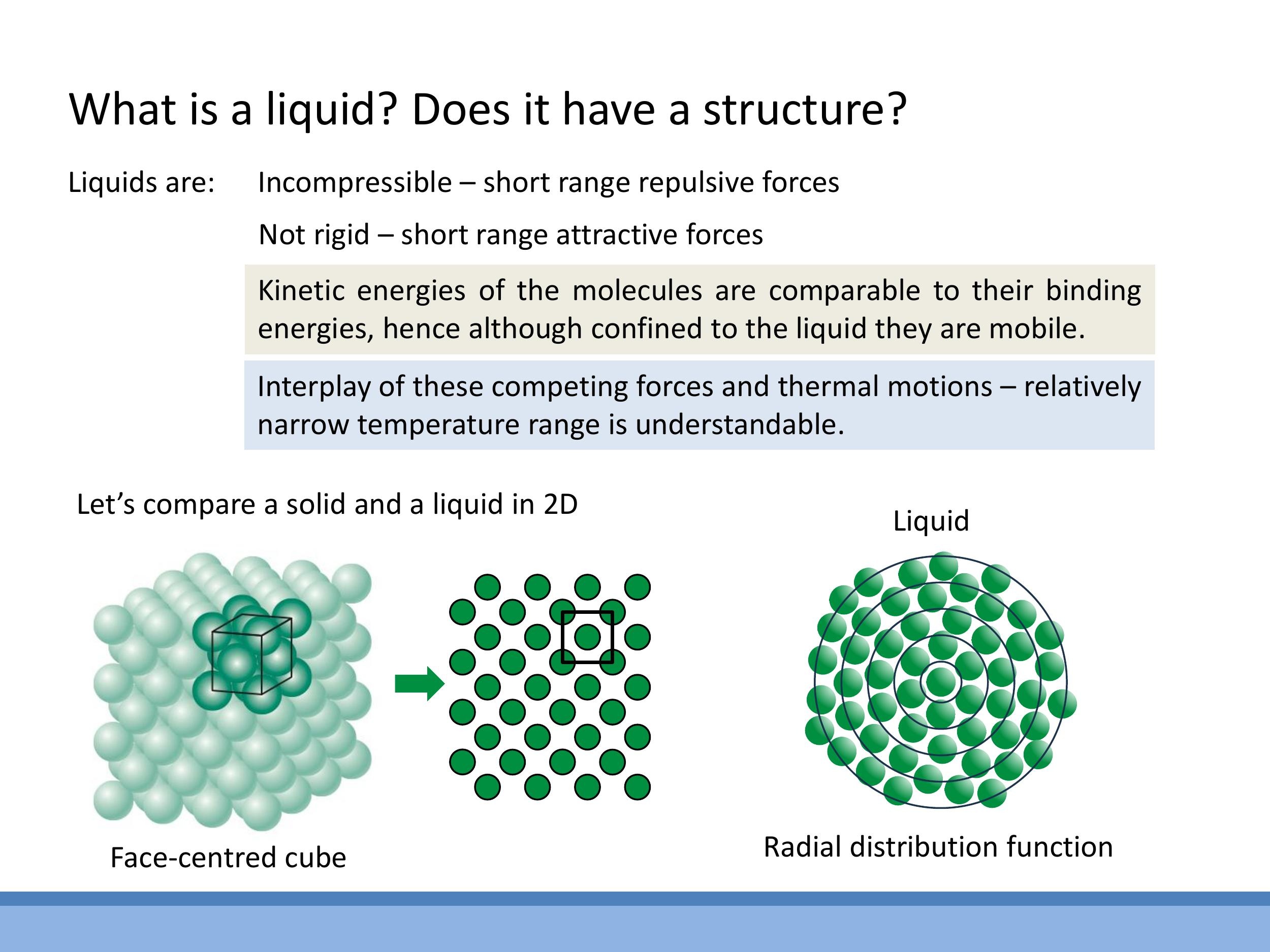

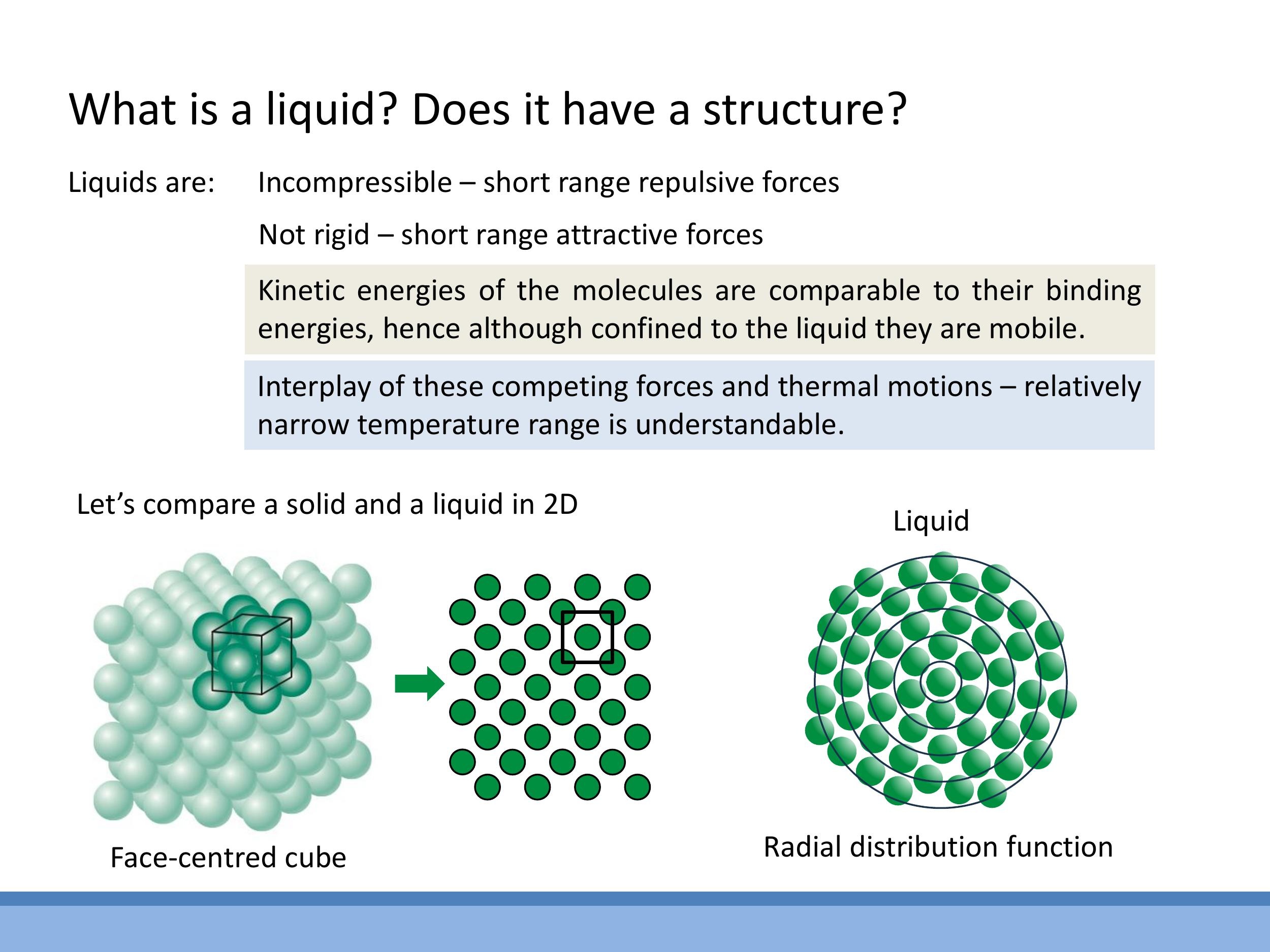

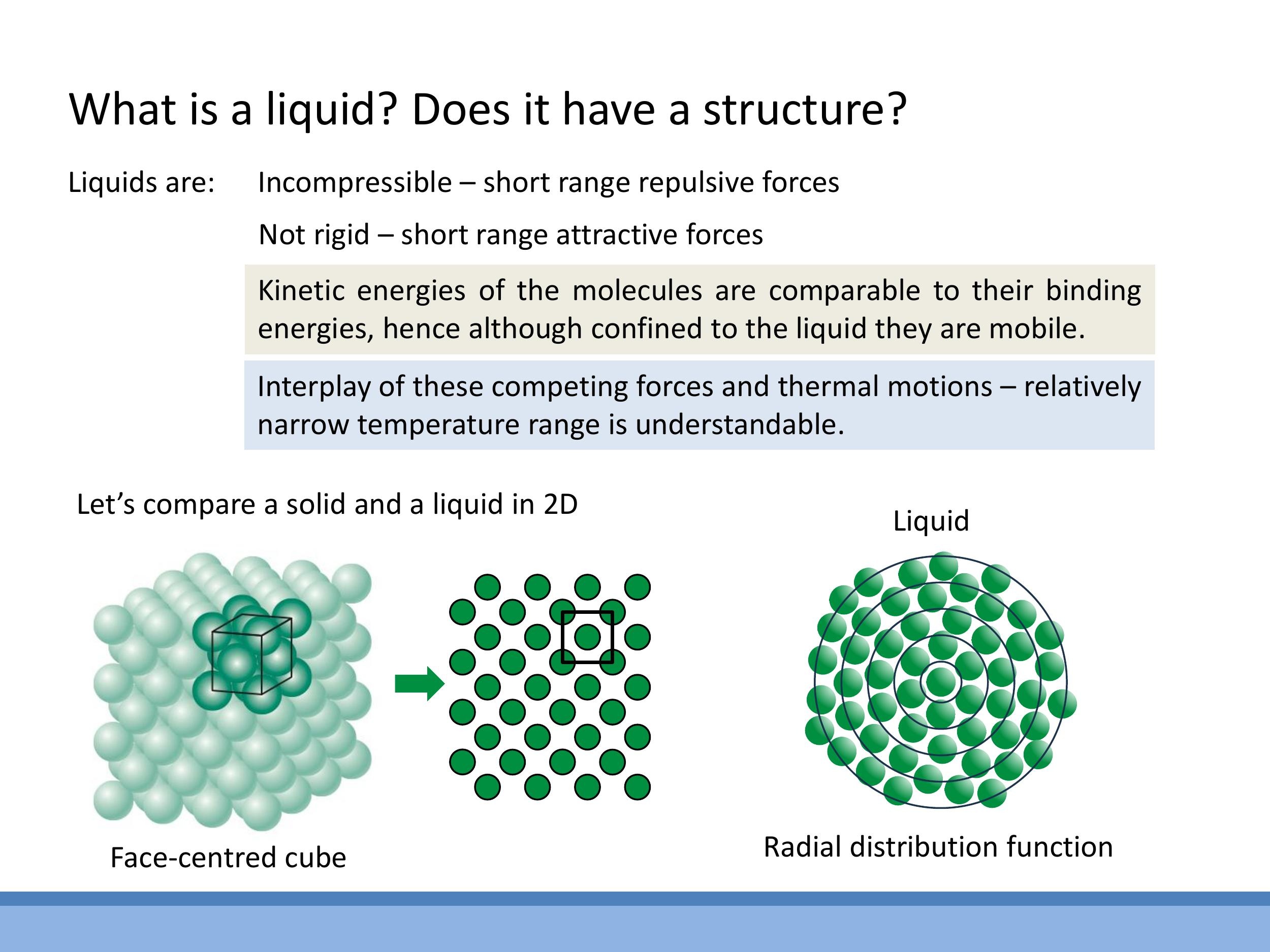

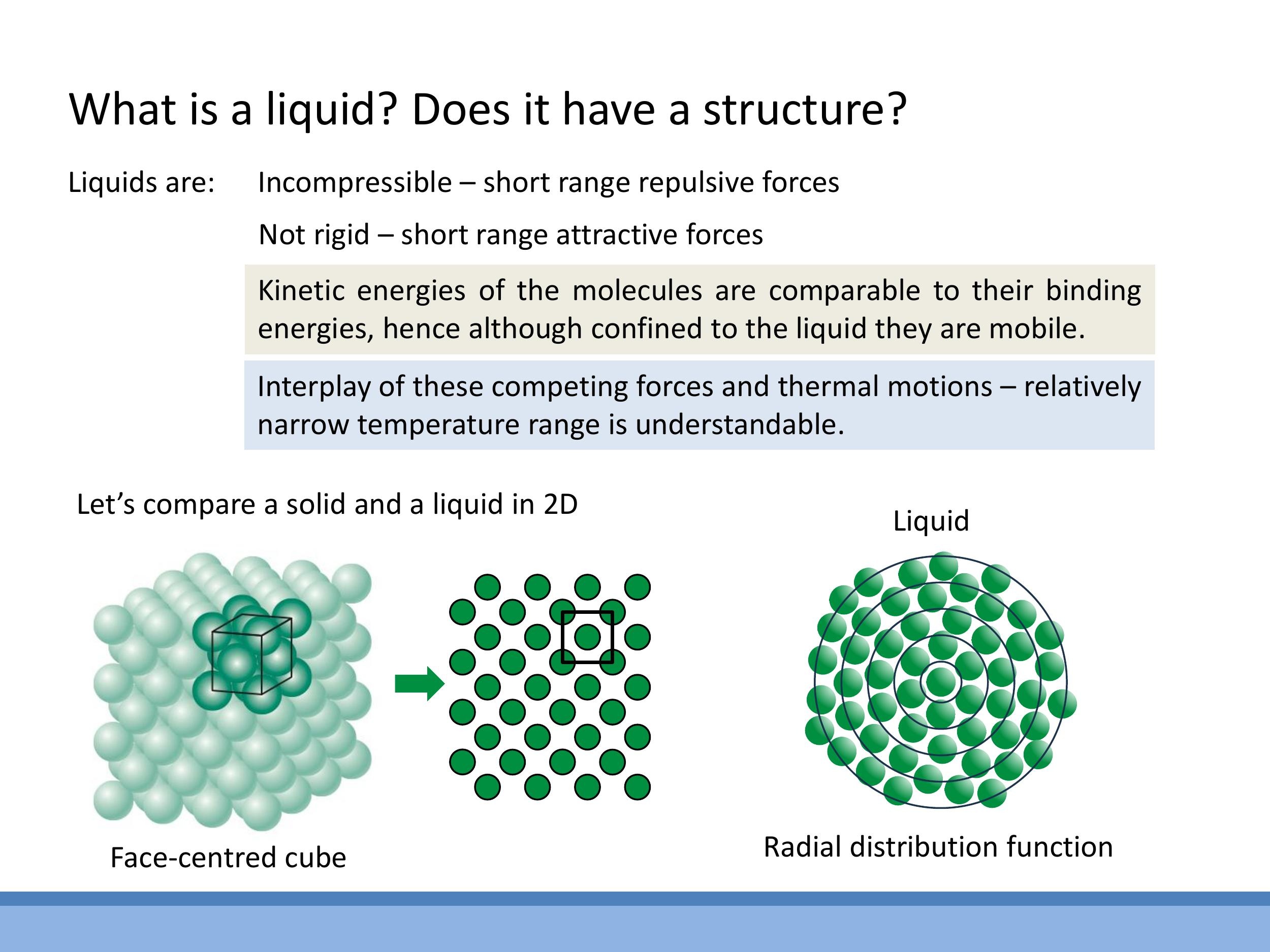

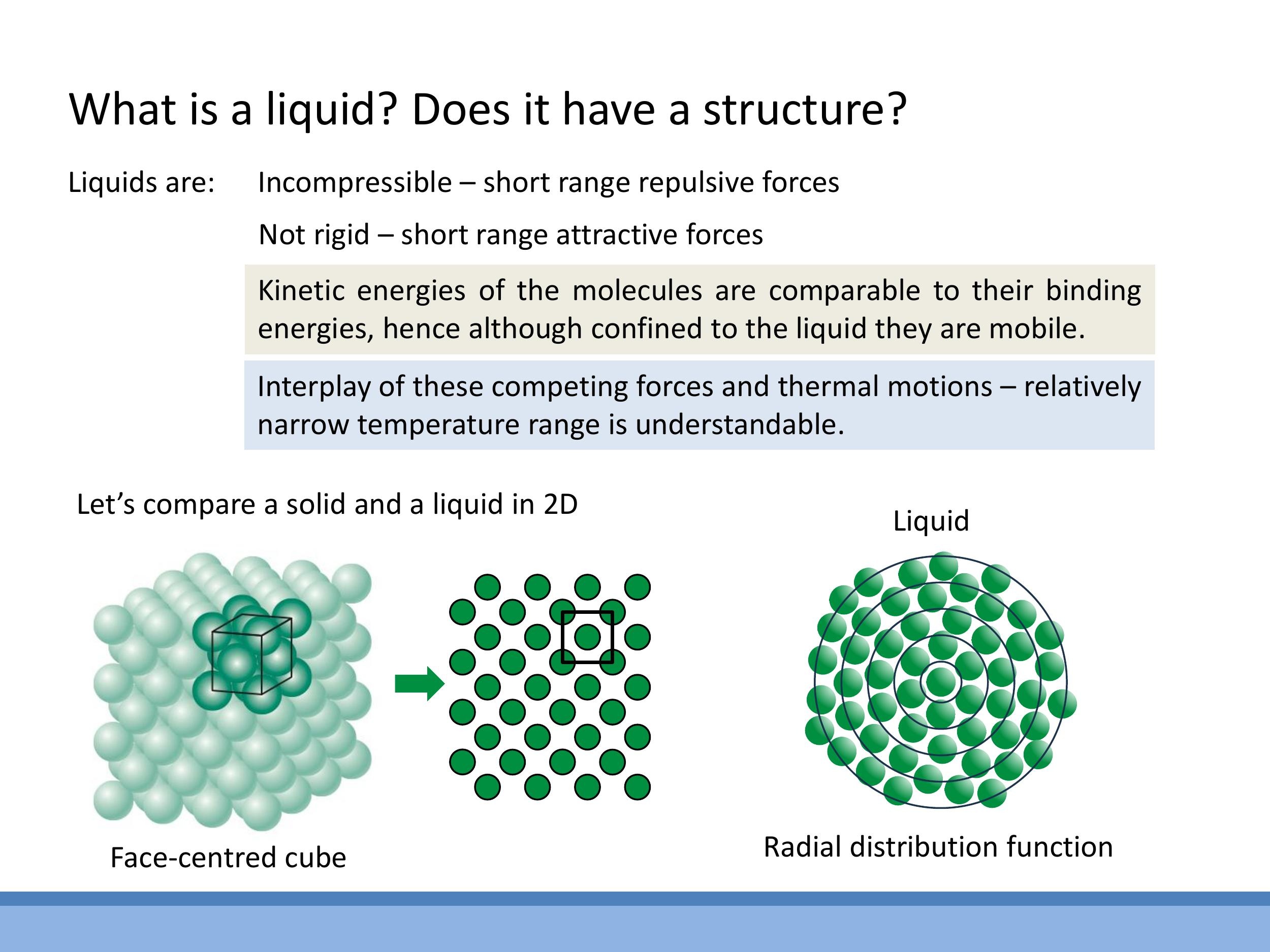

Liquids are characterised by distinct physical properties. They are largely incompressible, a characteristic stemming from the steep short-range repulsive forces that prevent molecules from being squeezed much closer together. However, unlike solids, liquids are not rigid; the attractive forces between molecules are not strong enough to lock them into fixed positions, allowing molecules to flow past one another. Liquids also exhibit viscosity, which is significantly higher than that of a gas, indicating resistance to shear.

The liquid state is defined by a delicate energy balance where the molecular kinetic energies are comparable to the bonding energies. If kinetic energies are much larger than bonding energies, molecules move freely, dominating over cohesive forces, resulting in a gas. Conversely, if kinetic energies are much smaller than bonding energies, atoms vibrate about fixed positions within a rigid structure, forming a solid. This comparable energy balance in liquids means molecules are mobile but still cohesive. This specific energetic condition explains why liquids typically exist over a relatively narrow temperature range; even small changes in temperature can tip the balance towards either the gaseous or solid phase.

# 2) Nearest neighbours and structural order: liquids vs solids

The structure of liquids can be distinguished from solids by examining their local atomic arrangements, particularly the number of nearest neighbours and the extent of long-range order. The number of nearest neighbours, or coordination number ($n$), refers to the number of atoms in direct contact with a central atom. For a typical liquid, the average coordination number is approximately $n \approx 10$ in three dimensions. This contrasts with close-packed crystalline solids, such as face-centred cubic (FCC) or hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structures, where each atom has $n = 12$ nearest neighbours. This close packing can be visualised as stacking cannonballs in a hexagonal array.

Crystalline solids exhibit long-range order, meaning they possess a periodic, repeating arrangement where every atom "sees" an identical local environment. In contrast, liquids only exhibit short-range order; local arrangements vary from atom to atom, and periodicity is lost over larger distances. It is worth noting that some solids, such as glass, are amorphous and lack long-range order, resembling the short-range order found in liquids.

# 3) The radial distribution function g(r): measuring structure quantitatively

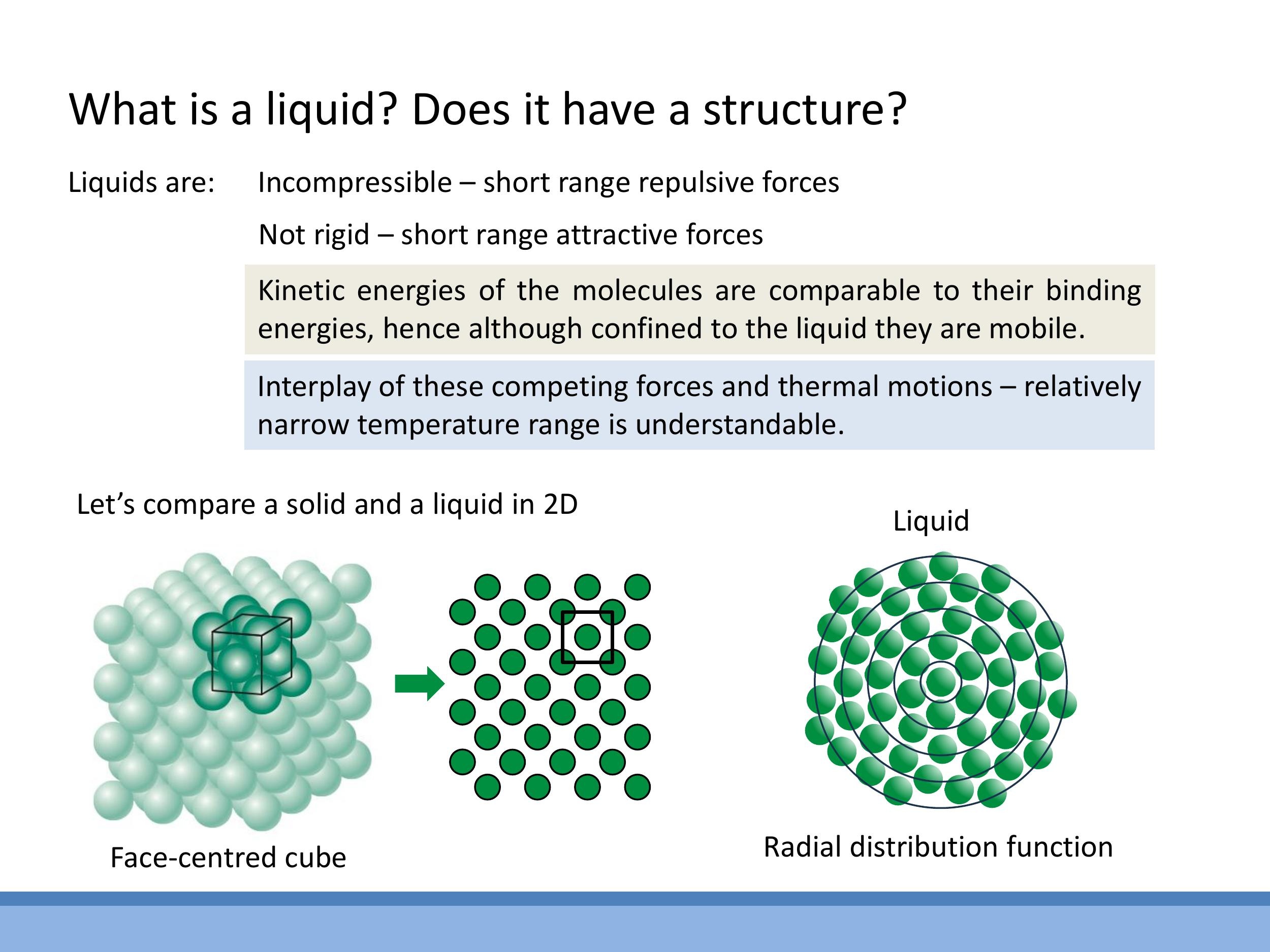

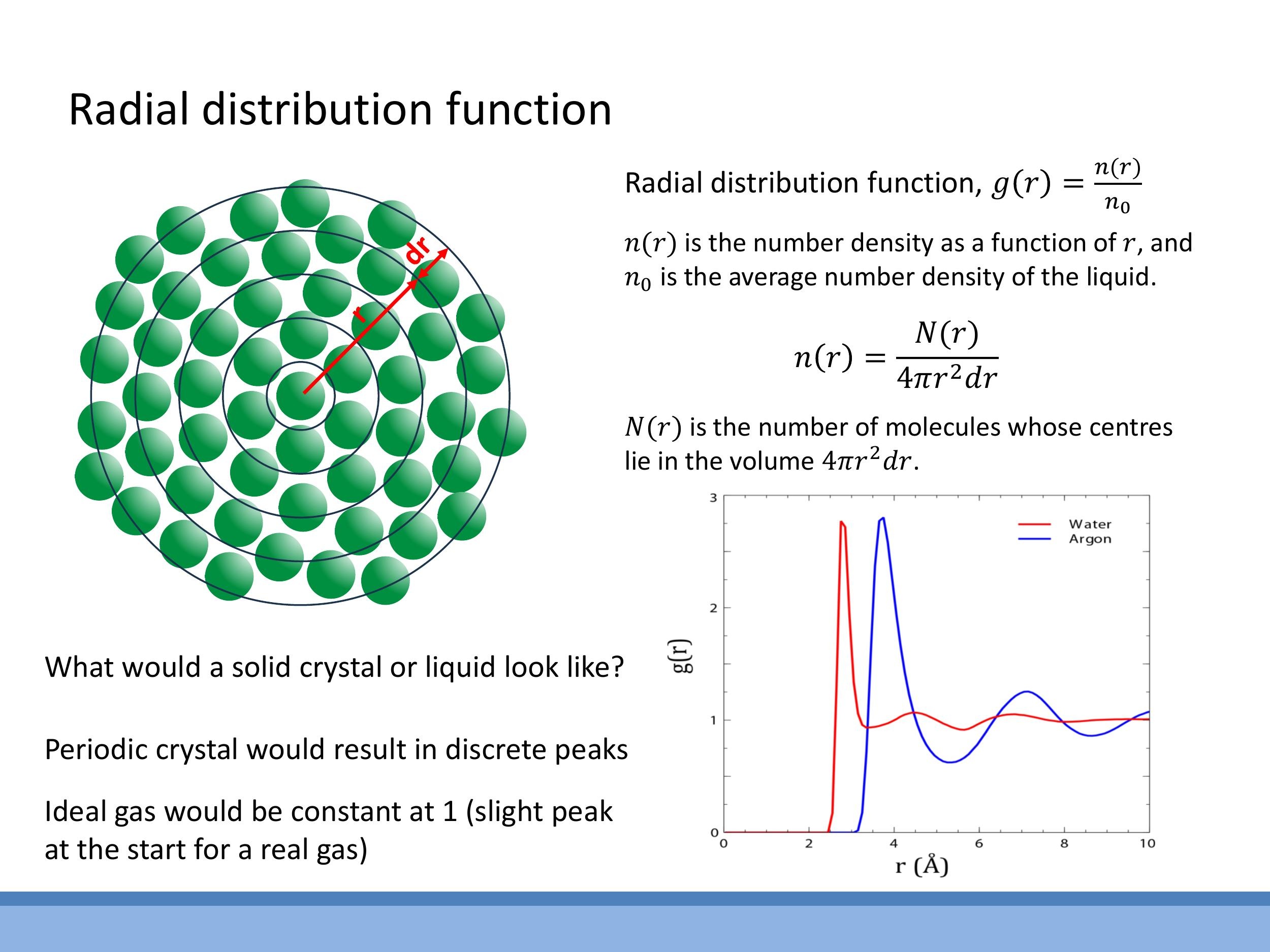

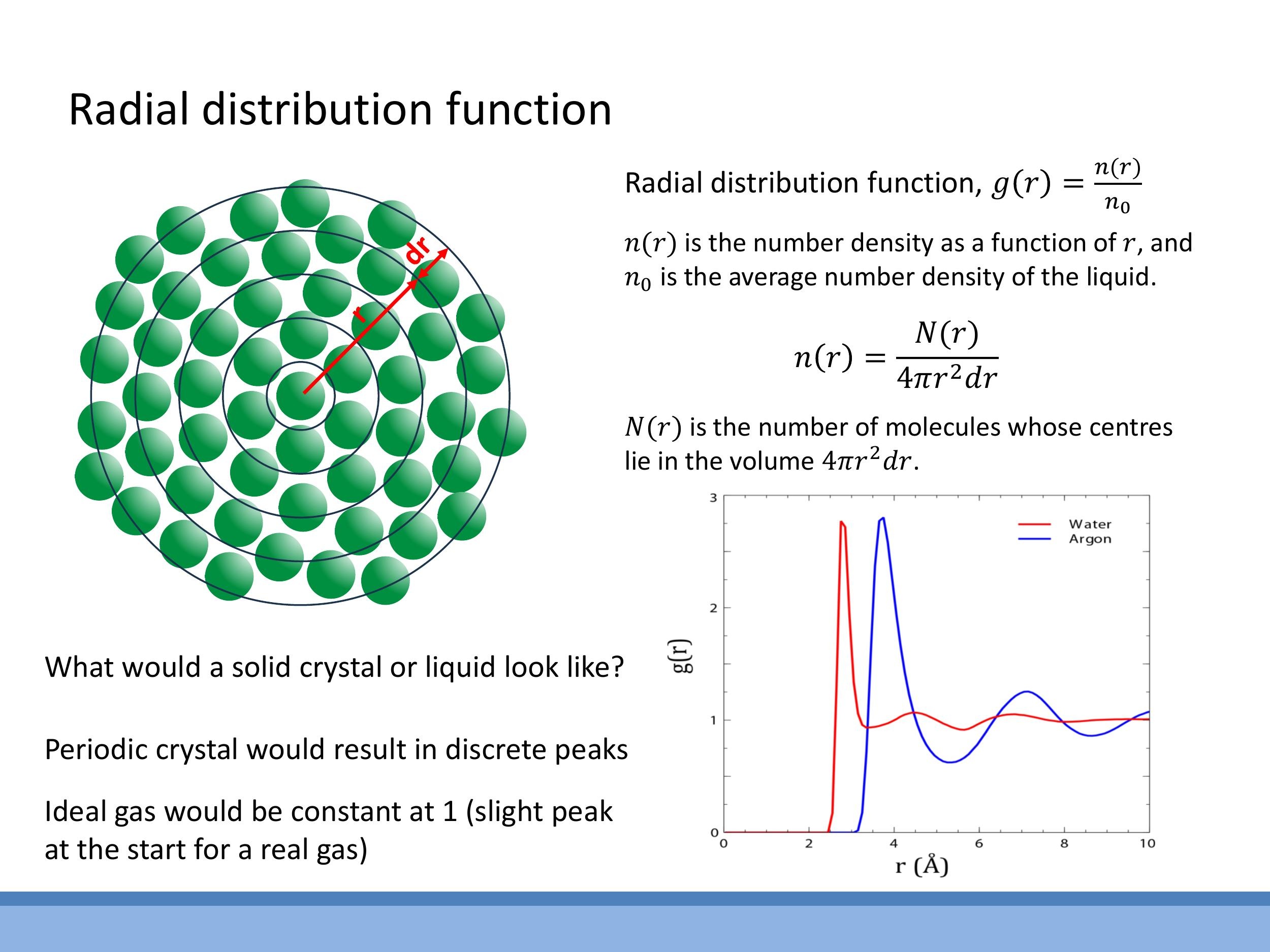

The radial distribution function, $g(r)$, quantitatively describes the structural order within a material by indicating the probability of finding a particle at a given distance $r$ from a reference particle. It is defined as the ratio of the local number density $n(r)$ at distance $r$ to the average number density $n_0$ of the system: $g(r) = n(r)/n_0$. The local number density $n(r)$ is given by $n(r) = N(r)/(4\pi r^2 dr)$, where $N(r)$ is the number of molecules whose centres lie within a spherical shell of thickness $dr$ at distance $r$.

The qualitative signatures of $g(r)$ vary distinctly for different phases of matter. For liquids, $g(r)$ typically shows a pronounced first peak corresponding to the nearest neighbours, reflecting the short-range order. Subsequent peaks are broader and weaker, progressively damping out until $g(r)$ approaches 1 at large distances, indicating the loss of long-range order. In contrast, a crystalline solid would exhibit sharp, discrete peaks at fixed $r$ values, characteristic of its long-range periodic structure. An ideal gas, with no intermolecular interactions, would show $g(r) = 1$ for all $r$, as all separations are equally likely. A real gas, with weak short-range interactions, would appear mostly flat but might show a slight initial peak at very short distances. Plots for liquid water and argon, for instance, both show strong first peaks, but water's hydrogen-bond network results in a sharper and slightly shifted first shell compared to simple liquids like argon.

# 4) Surface tension γ: macroscopic definition and a simple film model

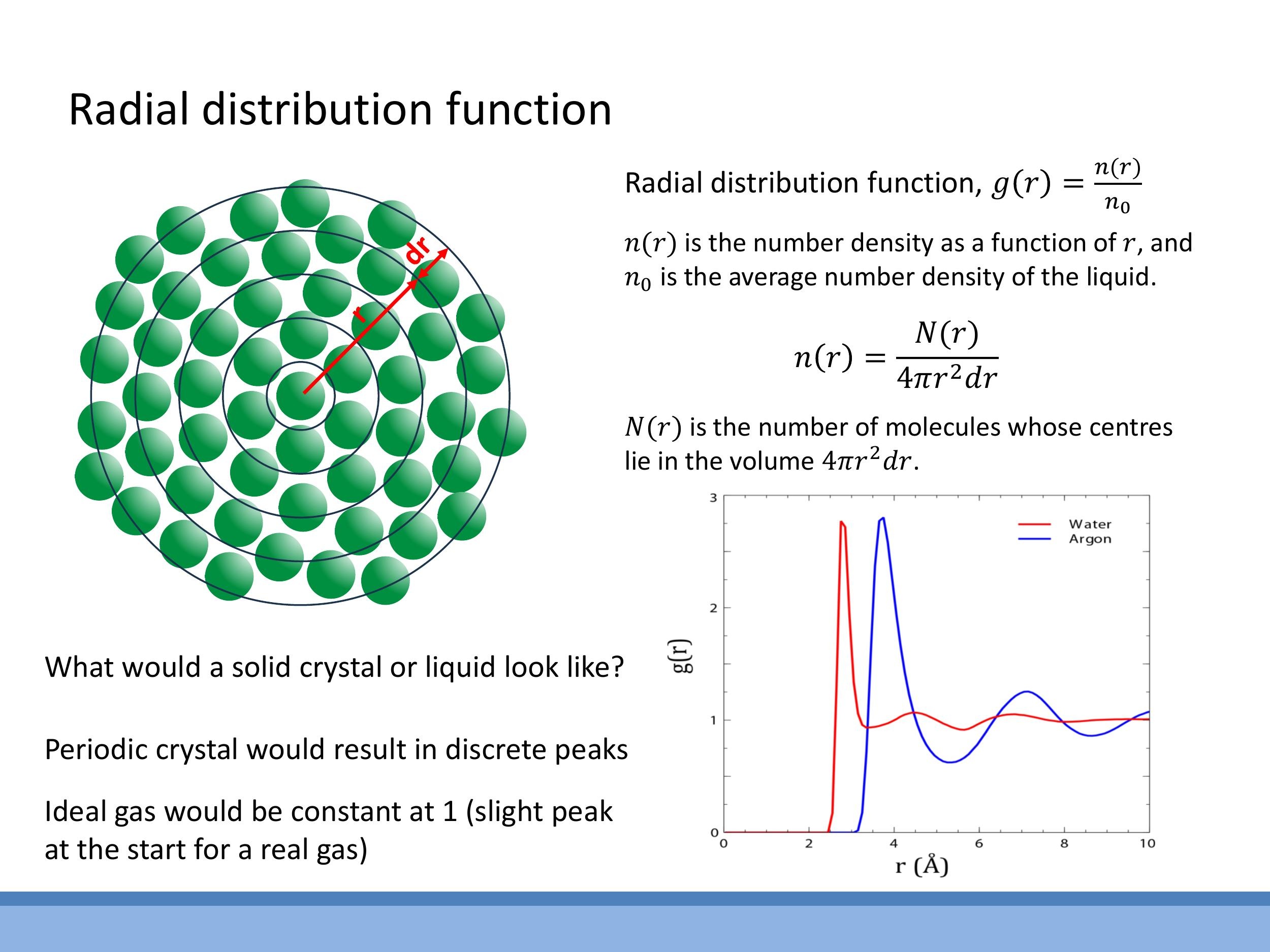

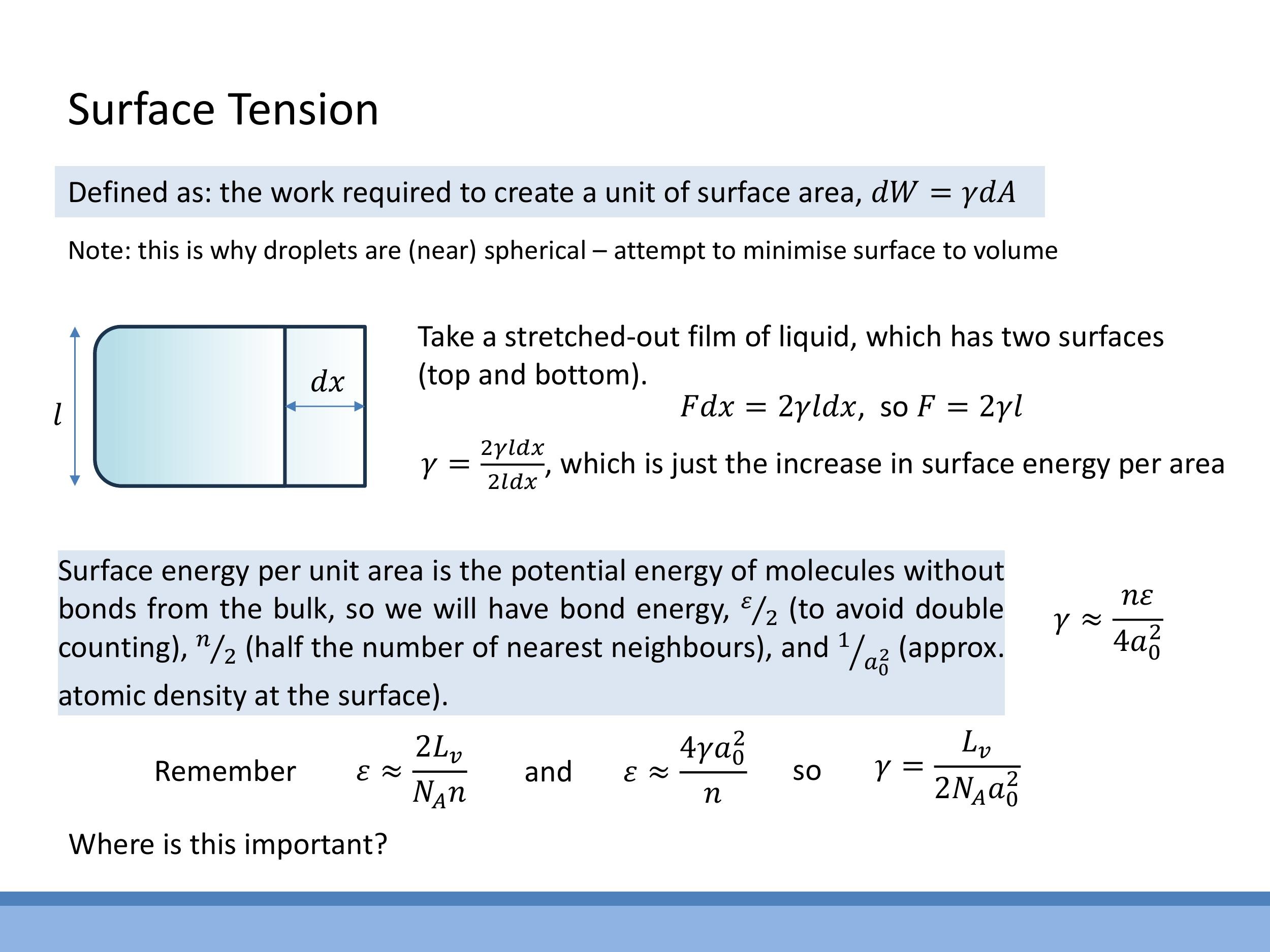

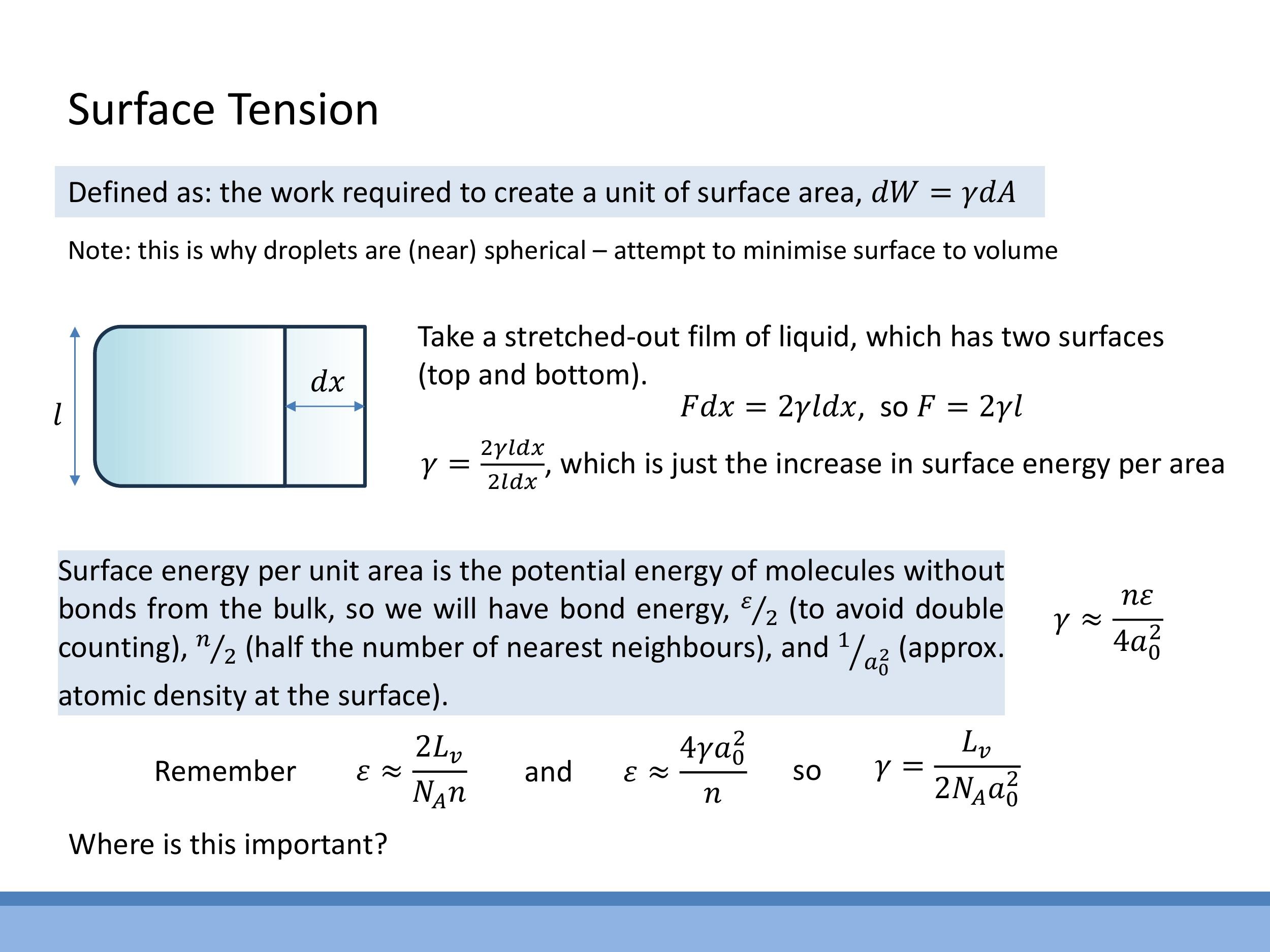

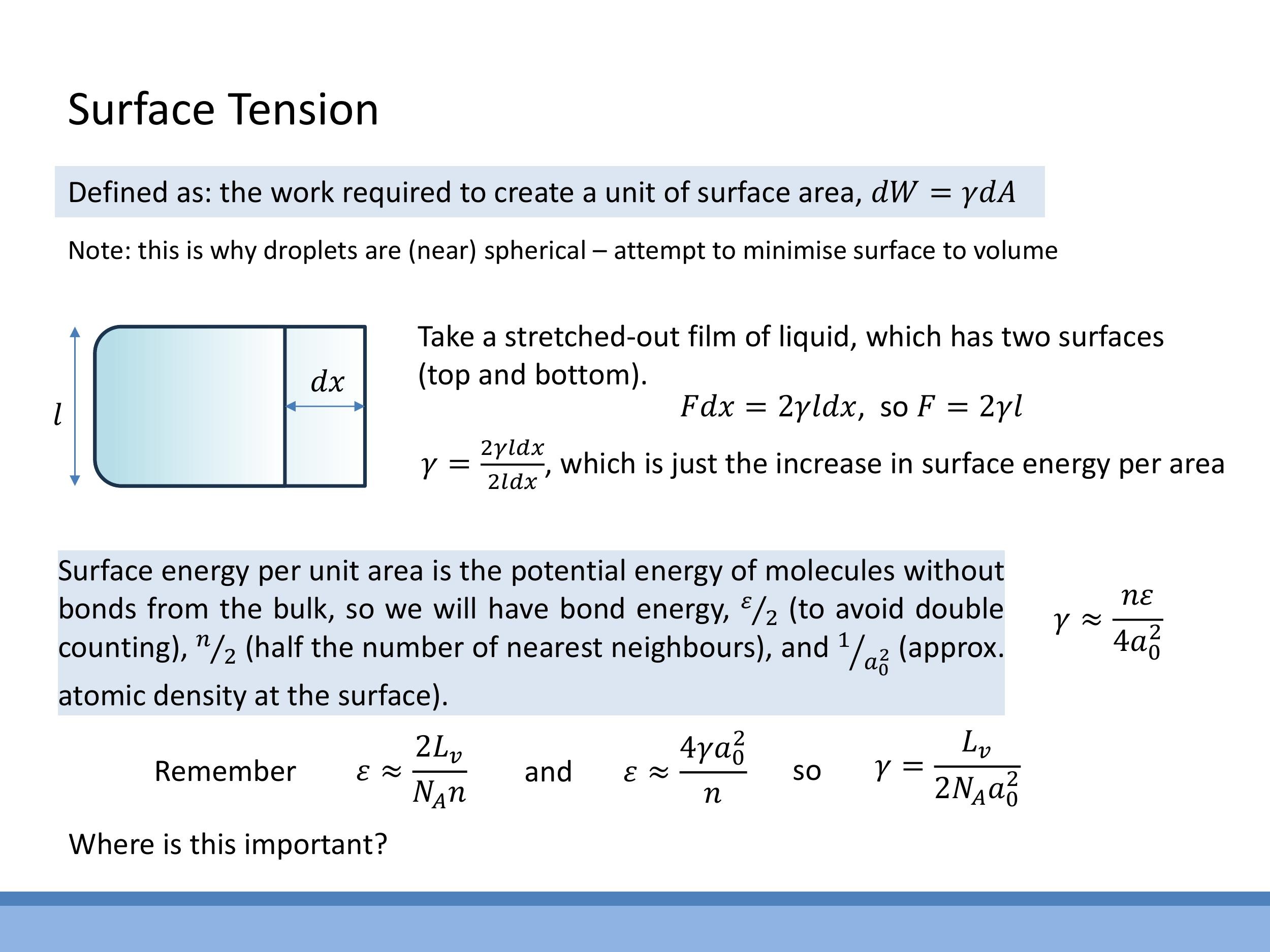

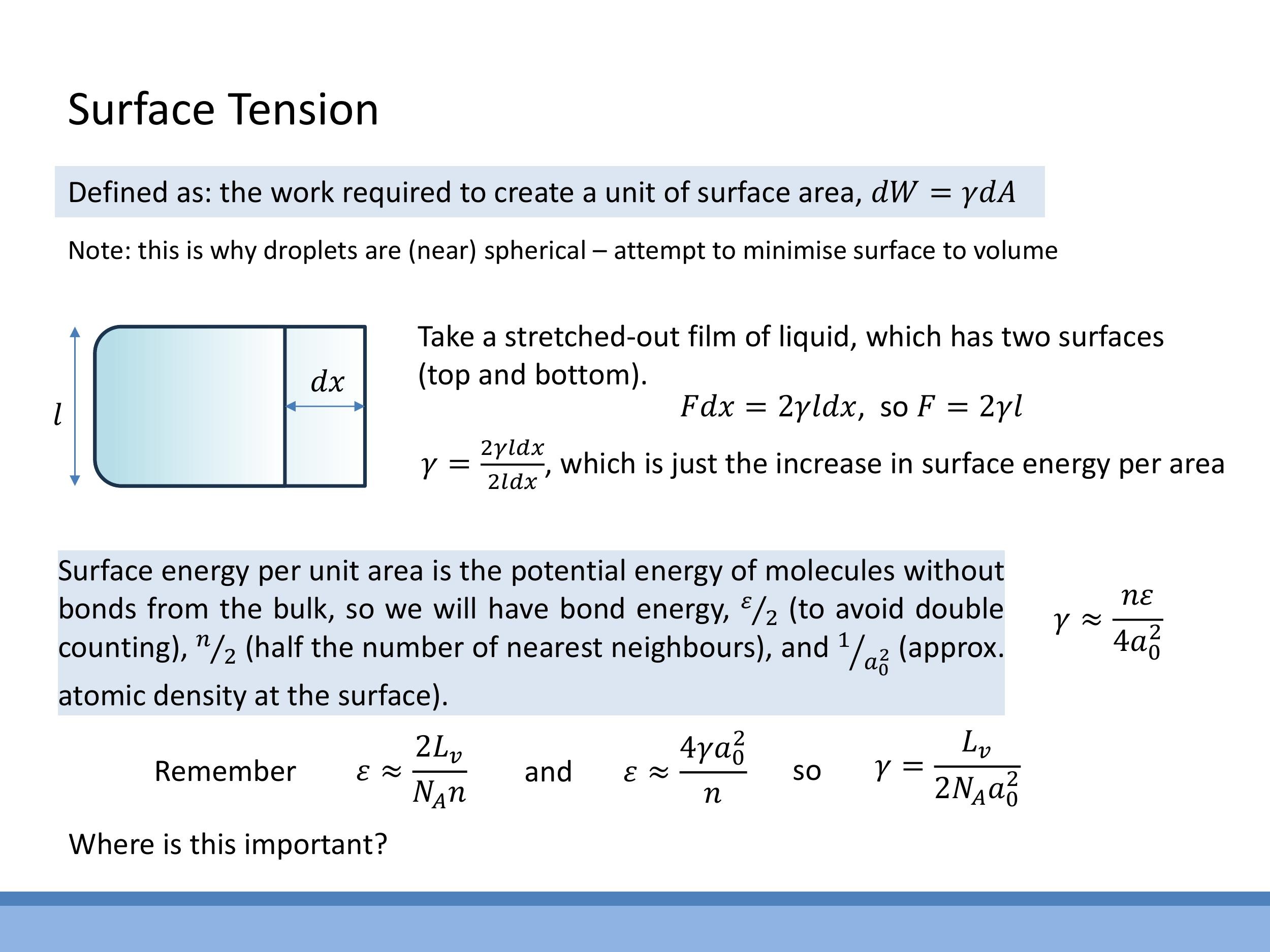

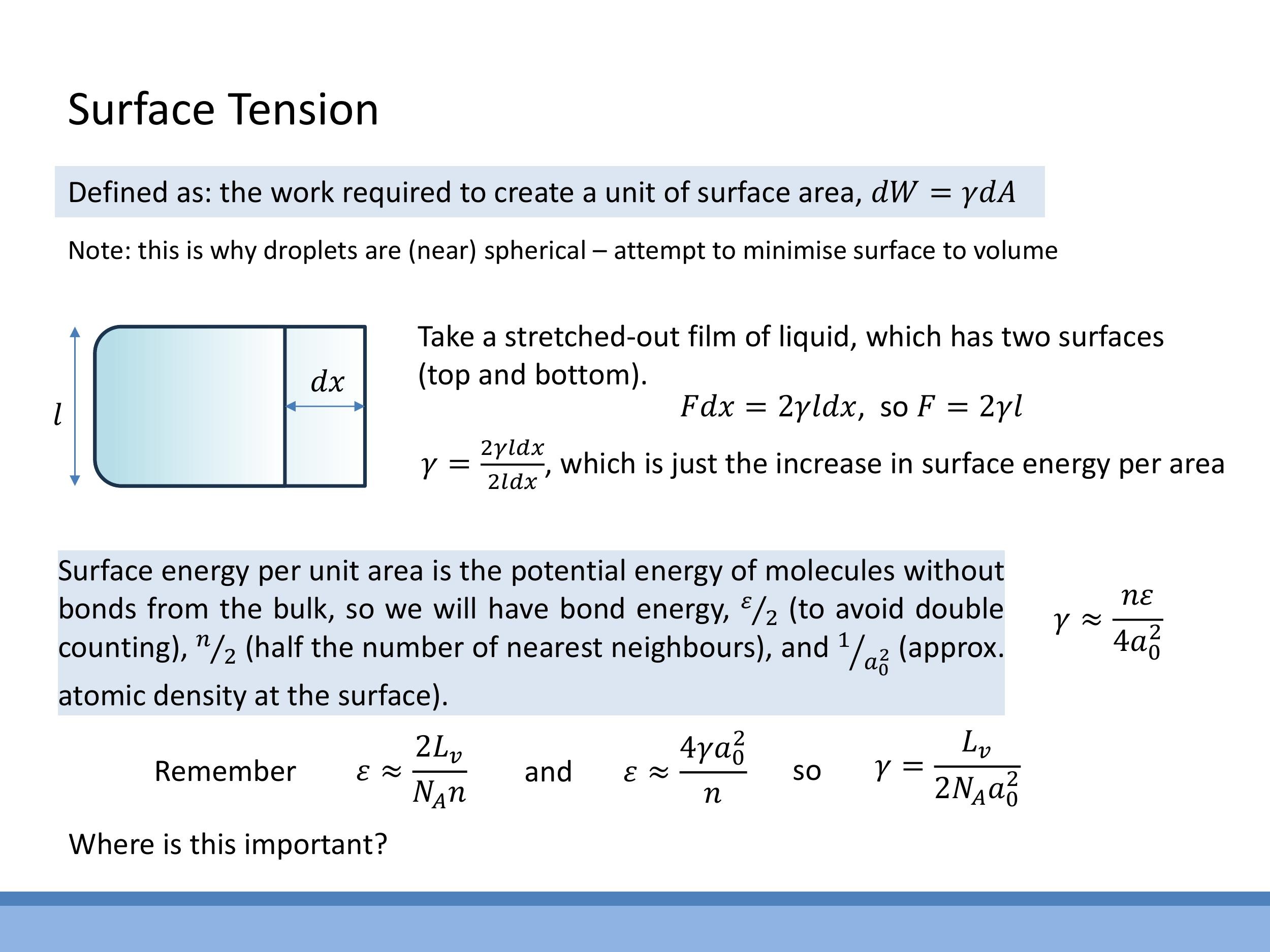

Surface tension ($\gamma$) is a macroscopic property of liquids, defined as the work required to create a unit of surface area. This relationship is expressed as $dW = \gamma dA$. This intrinsic tension explains why liquid droplets tend to adopt a spherical shape, as a sphere minimises surface area for a given volume, thereby minimising the total surface energy.

The concept of surface tension can be illustrated through a stretched liquid film. Consider a thin liquid film of width $l$ that is stretched by an infinitesimal distance $dx$. Since the film has two surfaces (a top and a bottom), the total increase in surface area is $2l \, dx $. The work done by the pulling force $ F $ over the distance $ dx $ must equal this increase in surface energy: $ F \, dx = \gamma (2l \, dx) $. This derivation leads to the relationship $ F = 2\gamma l $. This equation confirms that surface tension has dimensions of energy per unit area (e.g., $ \text{J m}^{-2} $) or, equivalently, force per unit length (e.g., $ \text{N m}^{-1}$).

# 5) Microscopic link: from γ to bond energy ε and back to L_v

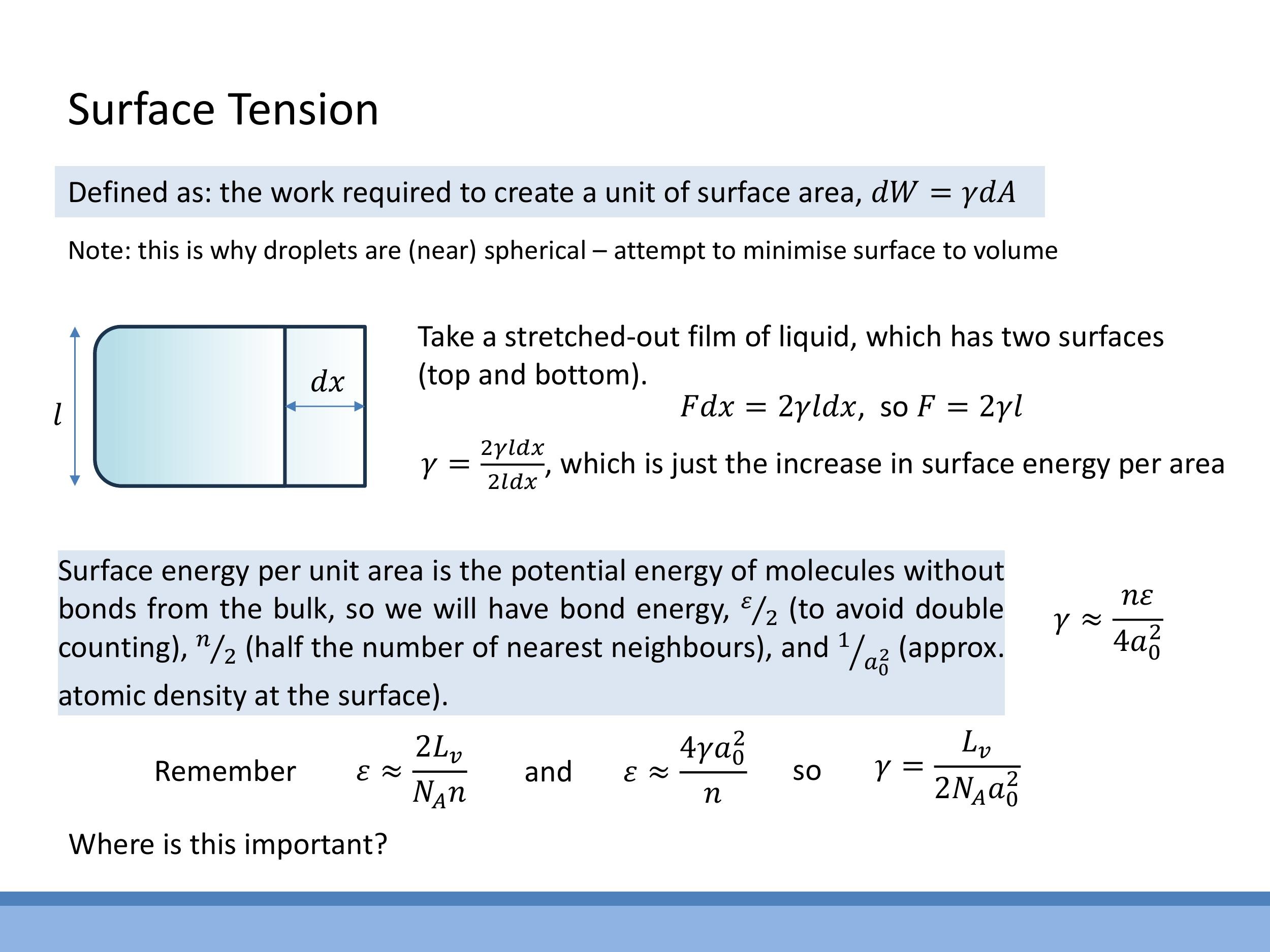

The macroscopic phenomenon of surface tension can be linked to the microscopic bond energy ($\varepsilon$) by considering the "missing bonds" at a liquid's surface. Molecules at the surface have fewer neighbours compared to those in the bulk, resulting in a higher potential energy. Approximating the energy associated with these missing bonds, the surface energy per unit area ($\gamma$) scales with the bond energy per molecule ($\varepsilon/2$, to avoid double counting), the fraction of missing neighbours (approximately $n/2$), and the surface number density (approximately $1/a_0^2$, where $a_0$ is the atomic spacing). This leads to the approximate relationship: $\gamma \approx \frac{n\varepsilon}{4a_0^2}$.

This microscopic model of surface tension can be cross-linked with earlier macroscopic measures of bond energy. From previous derivations related to the latent heat of vaporisation ($L_v$), the bond energy per pair was approximated as $\varepsilon \approx \frac{2L_v}{N_A n}$, where $N_A$ is Avogadro's number and $n$ is the coordination number. Combining these two expressions for $\varepsilon$ yields a relationship between surface tension and latent heat: $\gamma = \frac{L_v}{2N_A a_0^2}$.

A worked example for liquid nitrogen demonstrates the consistency of these independent approaches. Given a surface tension of $\gamma \approx 4 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{N m}^{-1} $, a density of $ \rho \approx 800 \, \text{kg m}^{-3} $, a latent heat of vaporisation $ L_v \approx 5.6 \, \text{kJ mol}^{-1} $, and a coordination number $ n \approx 10 $, the atomic spacing $ a_0 $ can be estimated from the density and molecular size. Using these values, the bond energy calculated from $ L_v $ is approximately $ \varepsilon \approx 0.012 \, \text{eV} $, while the calculation from $ \gamma $ yields $ \varepsilon \approx 0.016 \, \text{eV}$. The agreement between these two independently derived, albeit crude, estimates within factors of order unity provides validation for the underlying physical models.

# 6) Capillarity in the world: where surface tension matters

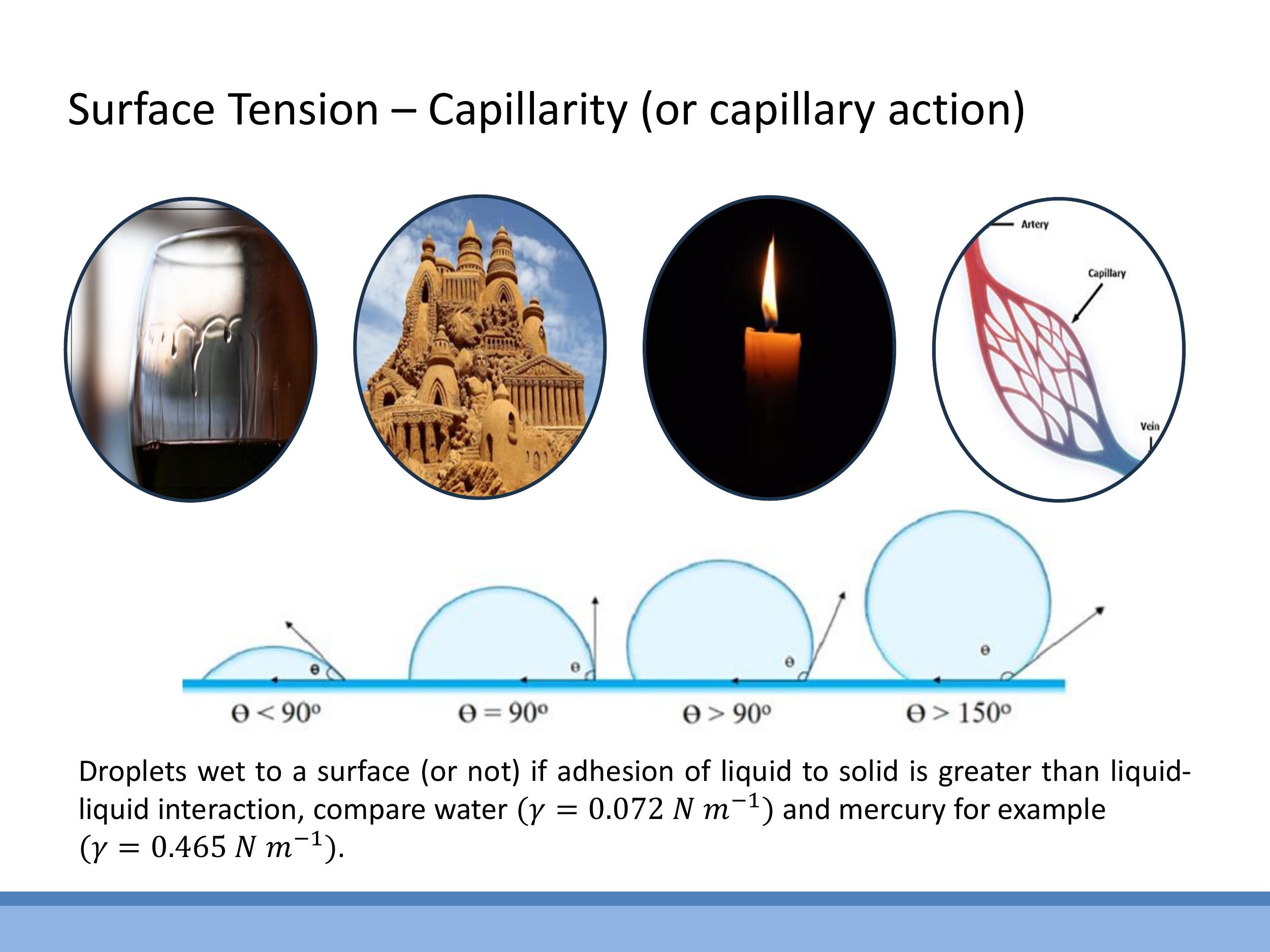

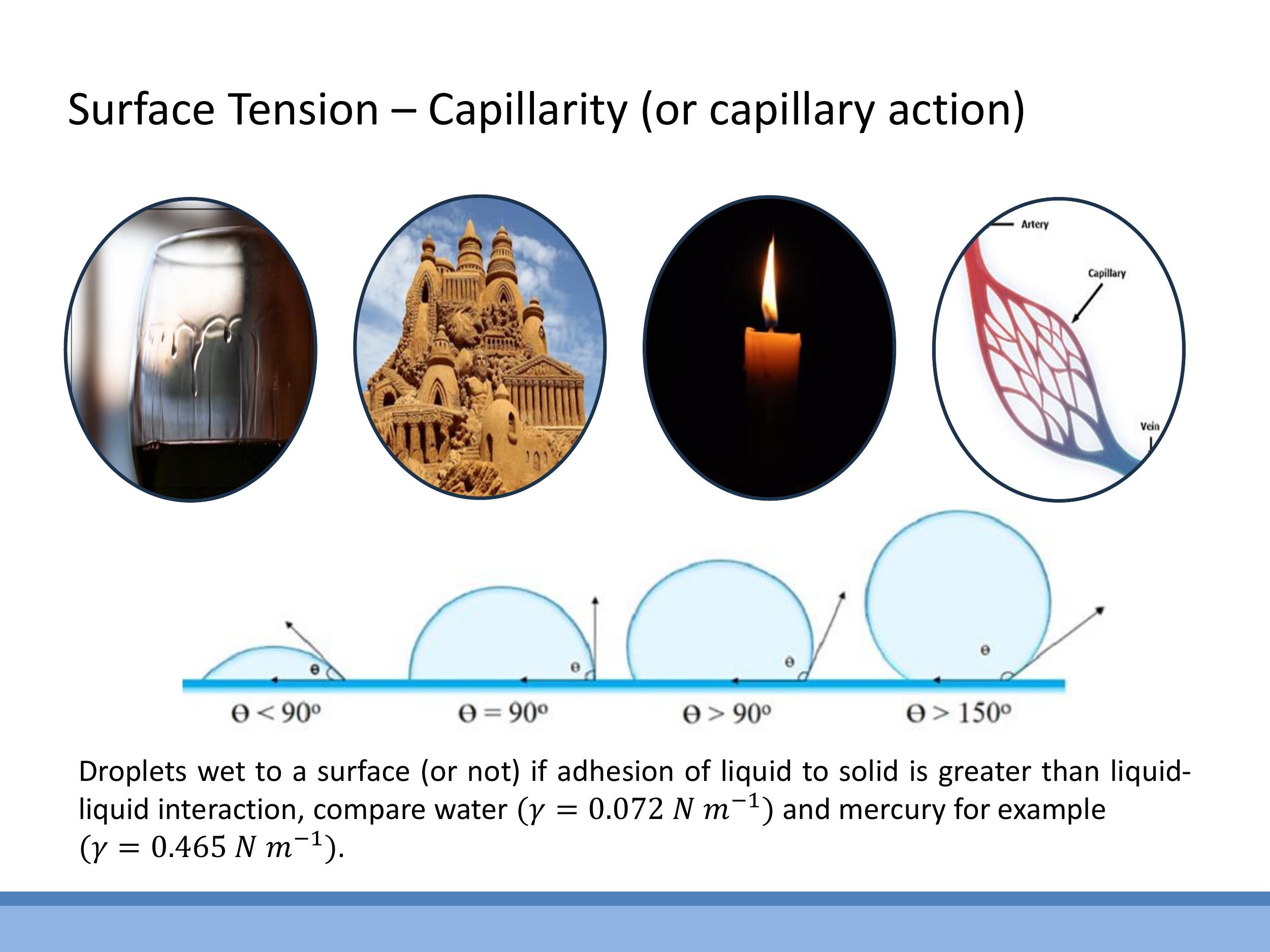

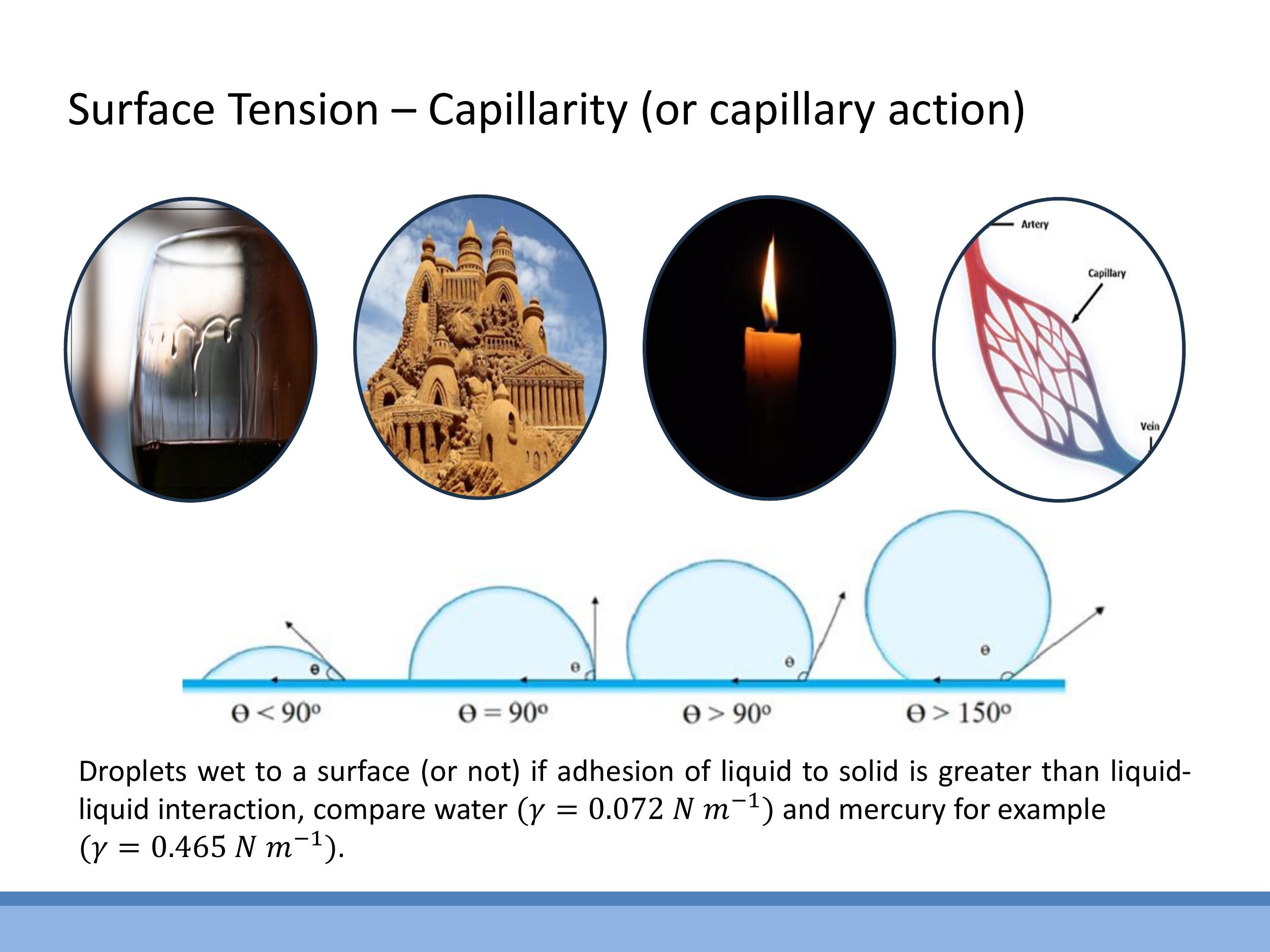

Surface tension plays a crucial role in numerous everyday phenomena and technological applications, a collective set of effects often termed capillarity. Examples include the formation of "tears of wine" on a glass, where differential surface tensions between alcohol and water drive fluid flows. In sandcastles, the surface tension of water binds individual sand grains, allowing them to form cohesive structures. Candles rely on capillary action to draw molten wax up the wick, where it then vaporises and burns; the wick acts as a transporter, not the primary fuel. Biologically, capillary networks in living organisms depend on surface tension and wetting properties for fluid transport.

The interaction between a liquid and a solid surface is described by its wettability, quantified by the contact angle ($\theta$). Wettability depends on the balance between adhesion (liquid-solid attraction) and cohesion (liquid-liquid attraction). For instance, water on clean glass exhibits excellent wetting with a contact angle of $\theta \approx 0^\circ$. In contrast, mercury on glass shows poor wetting, forming near-spherical droplets with a large contact angle. Typical surface tension values highlight this difference: water has $\gamma_{\text{water}} \approx 0.072 \, \text{N m}^{-1} $, while mercury has a much higher $ \gamma_{\text{mercury}} \approx 0.465 \, \text{N m}^{-1}$.

# 7) Quantifying curvature: pressure jump across a curved surface

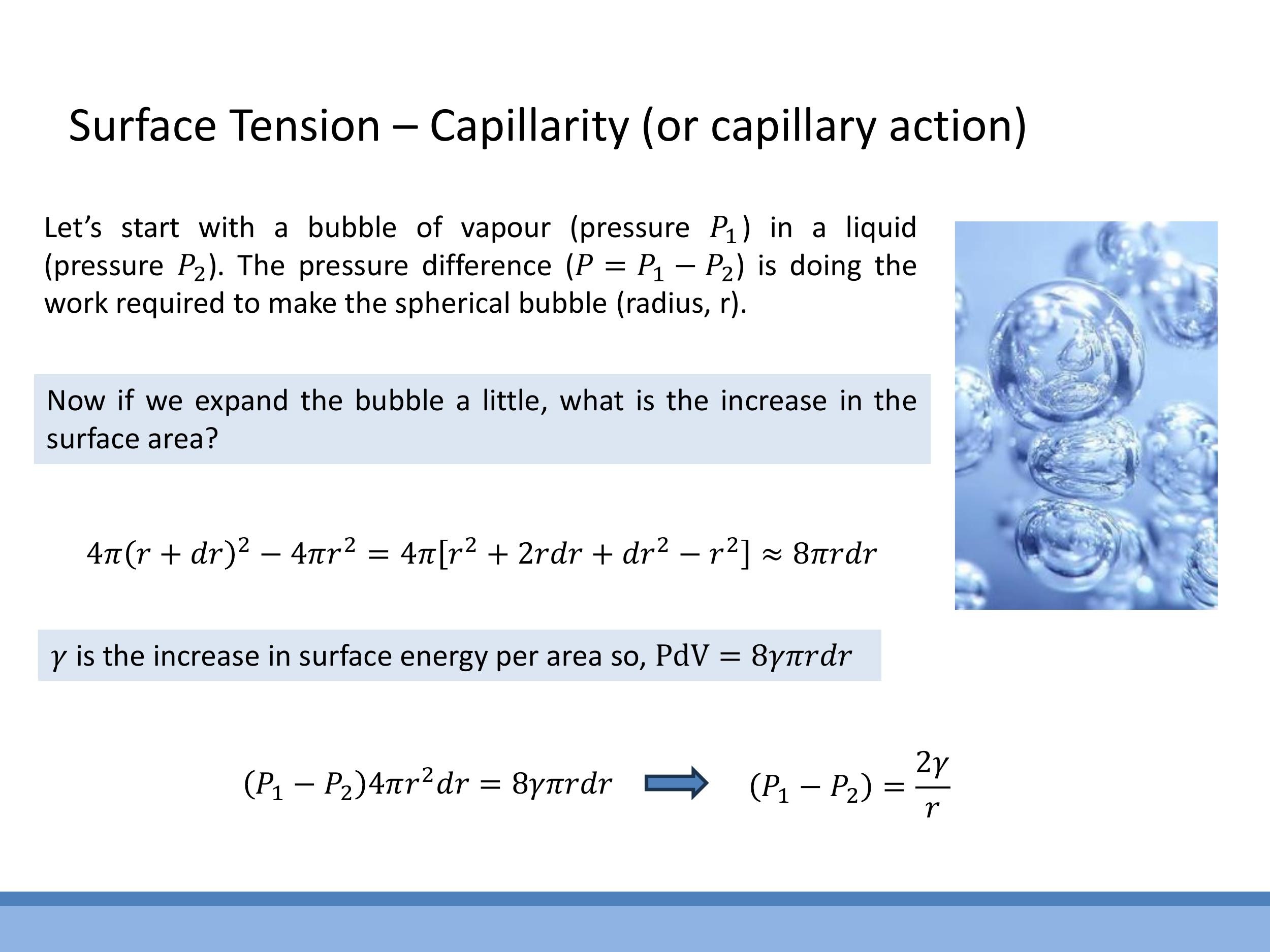

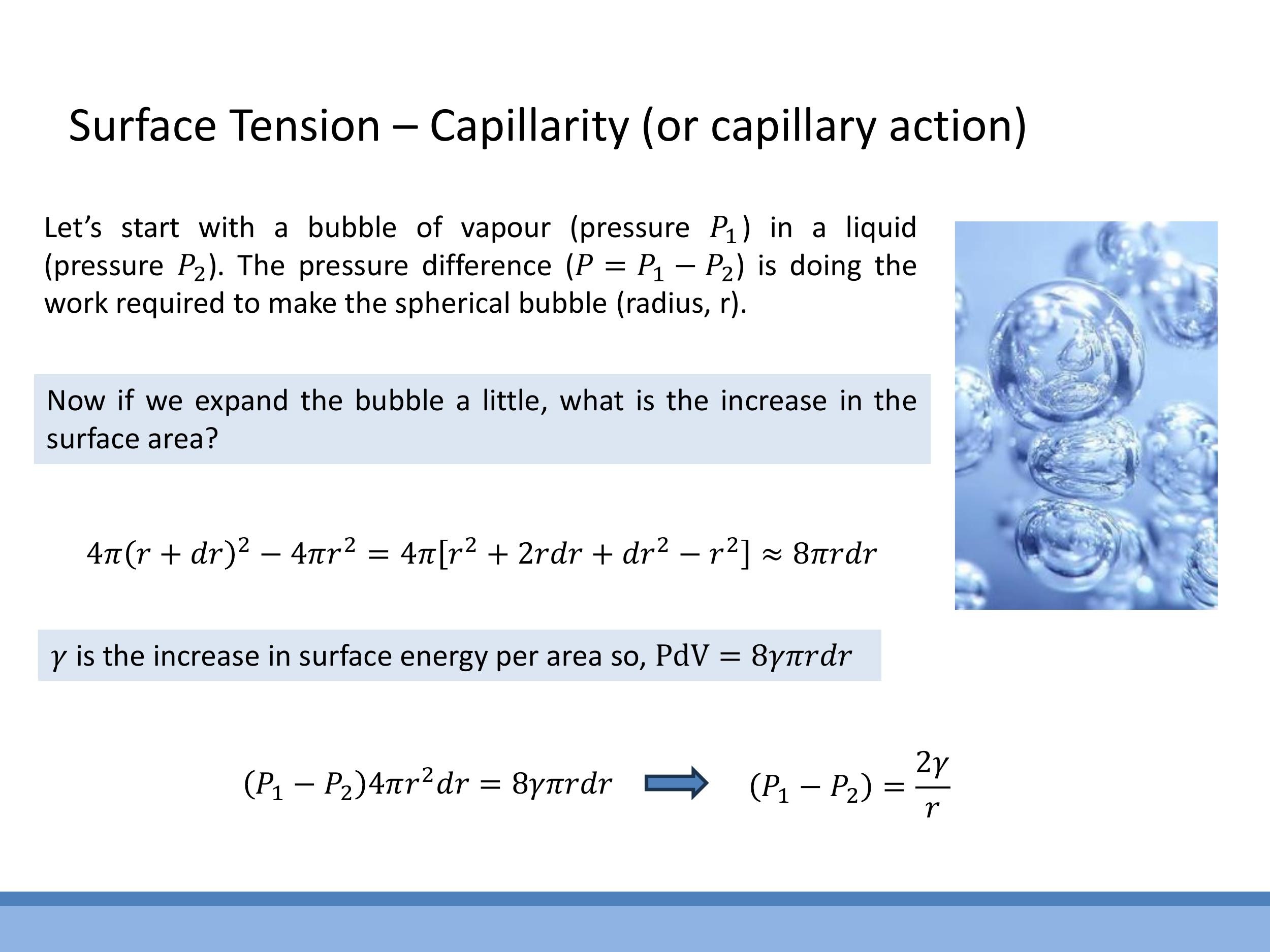

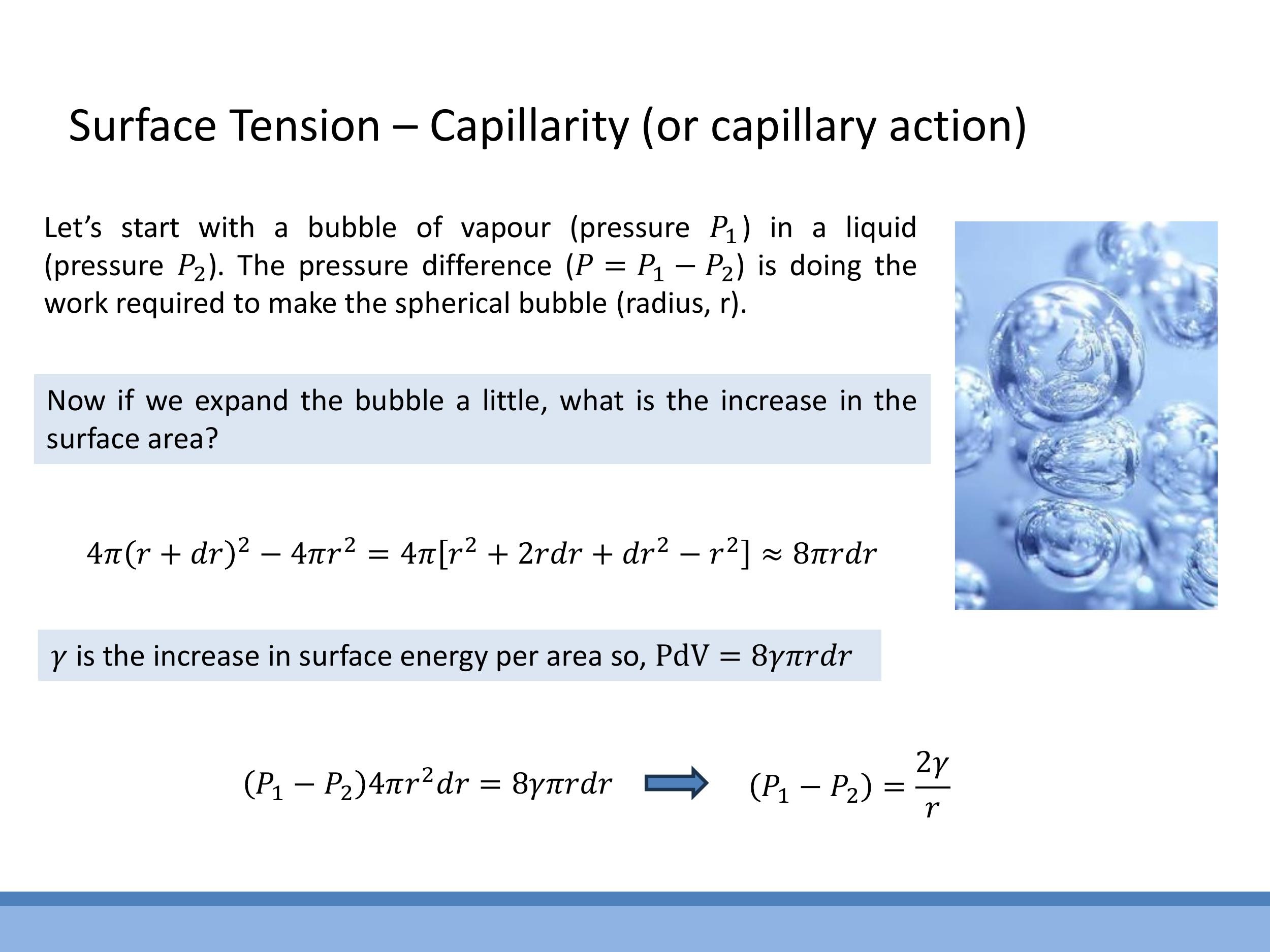

A curved liquid-vapour interface experiences a pressure difference across it, a phenomenon quantified by the Laplace pressure. This can be understood through a thought experiment involving a vapour bubble (internal pressure $P_1$) within a liquid (external pressure $P_2$). If the bubble's radius increases by an infinitesimal amount $dr$, the work done by the pressure difference $(P_1 - P_2)$ to expand its volume must be balanced by the increase in the bubble's surface energy.

The increase in surface area for a spherical bubble of radius $r$ when expanded by $dr$ is approximately $8\pi r \, dr $. The work done by the pressure difference is $ (P_1 - P_2) dV $, where $ dV = 4\pi r^2 dr $. Equating the work done to the increase in surface energy ($ \gamma \times \text{area increase} $) leads to the Laplace pressure equation for a spherical interface: $ (P_1 - P_2) = \frac{2\gamma}{r} $. This relationship indicates that higher curvature (smaller radius $ r$) requires a larger pressure difference to sustain the interface. Physically, smaller bubbles possess higher internal pressure compared to larger ones due to the greater curvature.

# 8) Capillary rise: balancing surface forces with hydrostatic weight

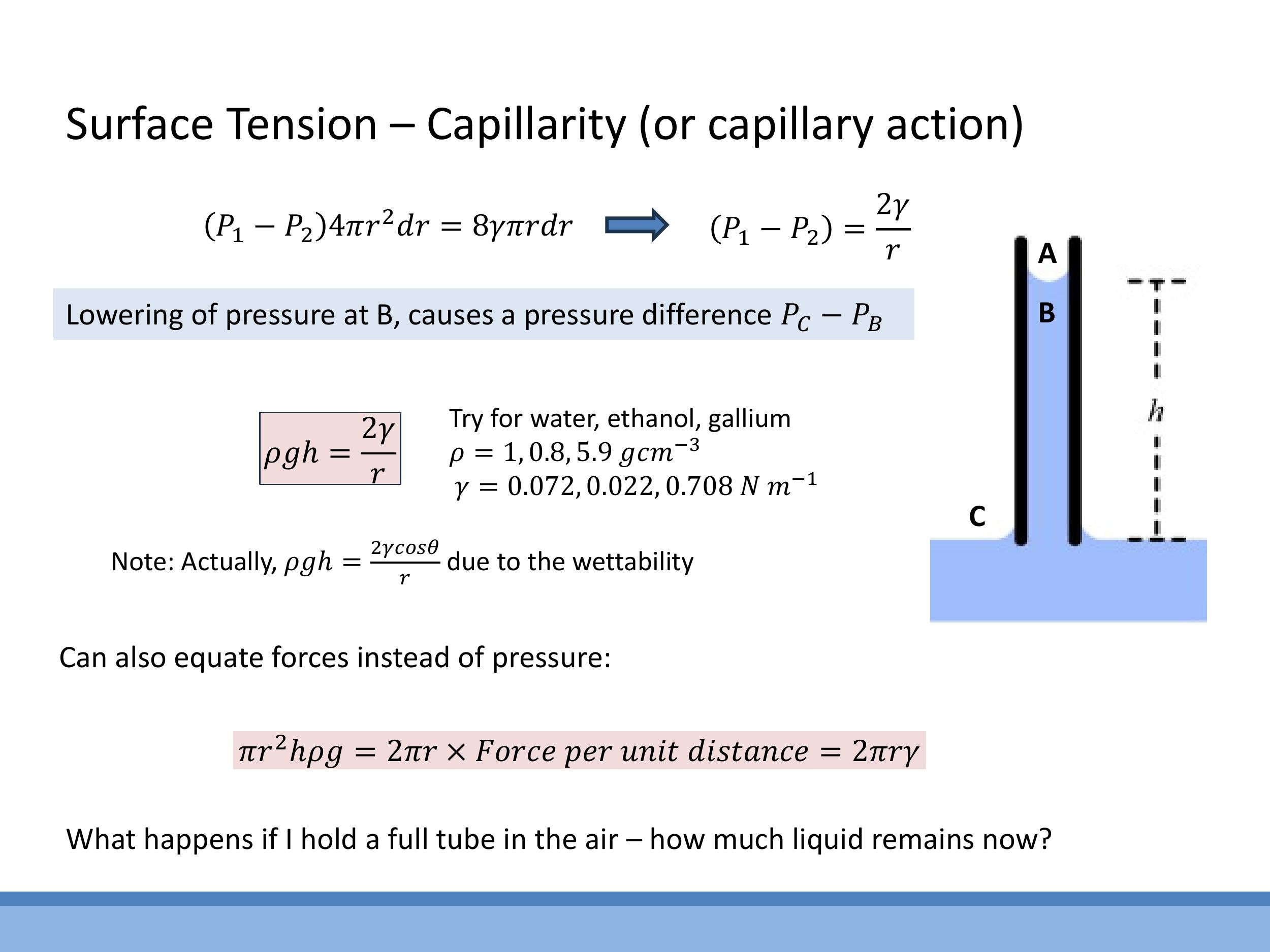

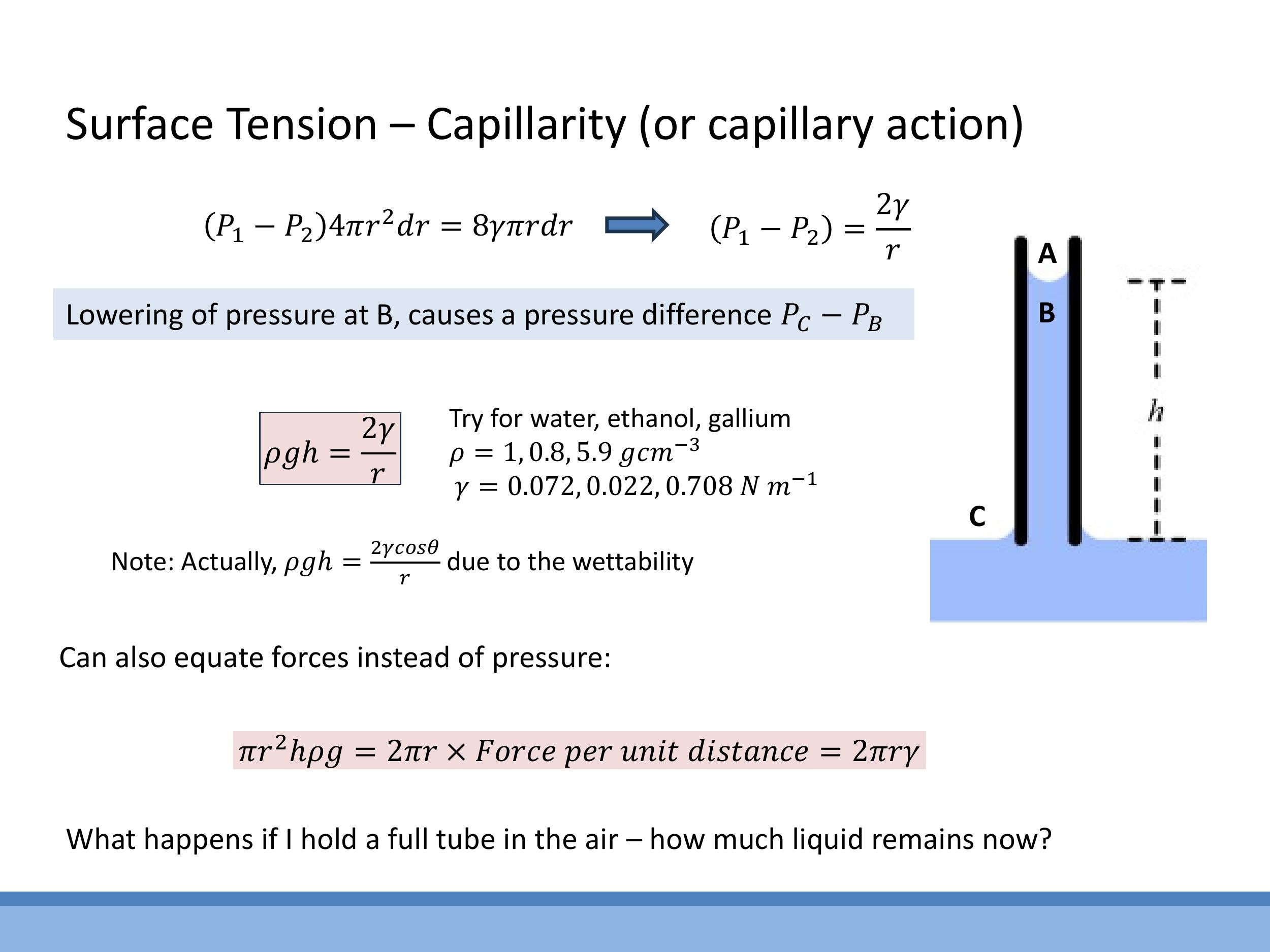

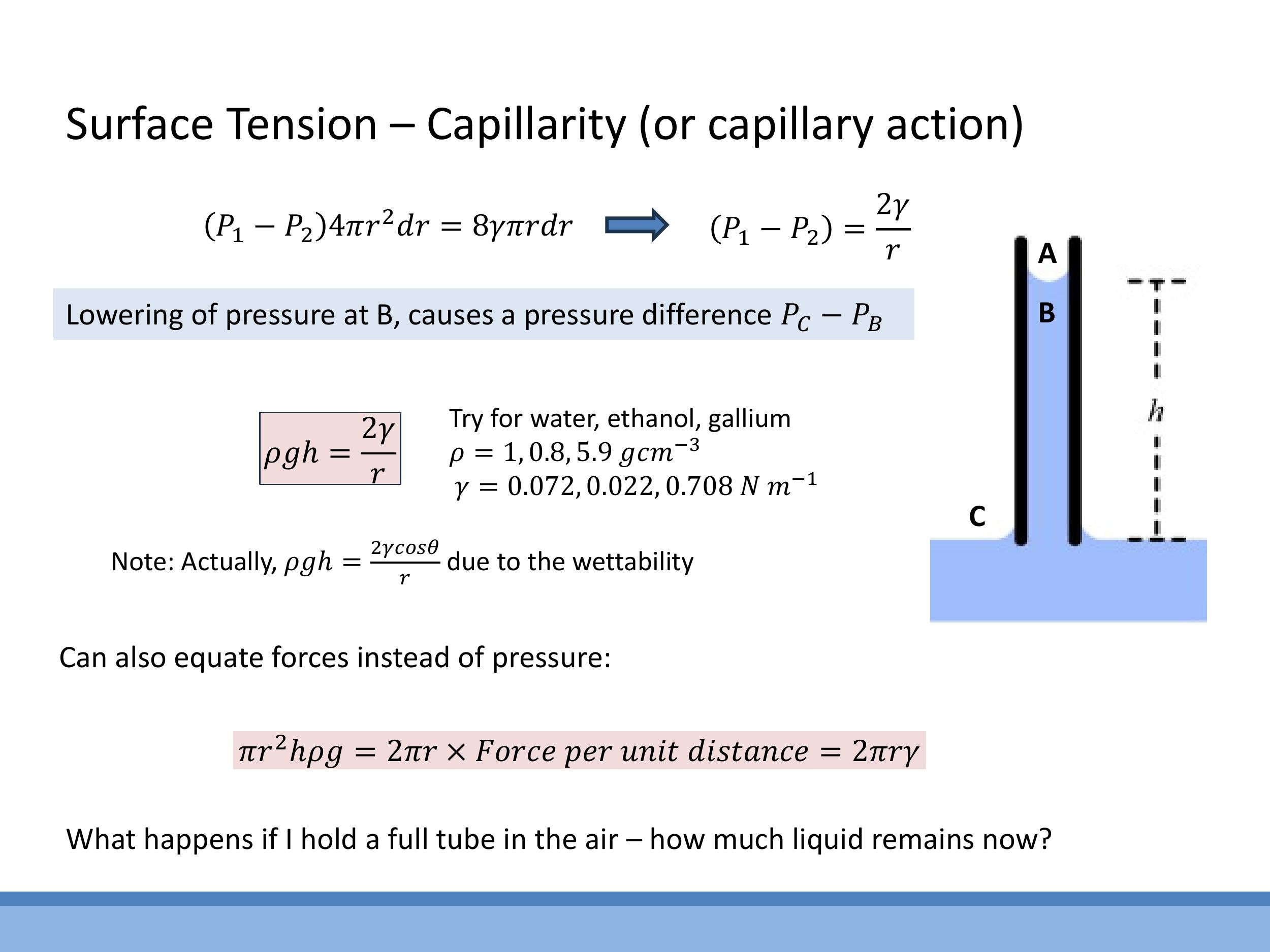

When a narrow tube is placed in a liquid, surface tension causes the liquid inside the tube to form a curved meniscus. This curved surface results in a lower pressure just beneath the meniscus inside the tube compared to the flat liquid surface in the reservoir outside. This pressure difference then supports a column of liquid of height $h$, which is balanced by the hydrostatic head of the liquid column.

The height of capillary rise can be derived via two equivalent routes. The pressure-based route equates the hydrostatic pressure of the liquid column to the Laplace pressure across the meniscus: $\rho g h = \frac{2\gamma}{r}$, assuming perfect wetting ($\theta = 0^\circ$). The force-based route balances the upward force due to surface tension along the circumference of the meniscus ($2\pi r \gamma$) with the downward gravitational force (weight) of the liquid column ($\pi r^2 h \rho g$), yielding the same result. For partial wetting, the more general formula is $\rho g h = \frac{2\gamma \cos\theta}{r}$.

This relationship reveals that the capillary rise height $h$ is inversely proportional to the tube's radius $r$; finer tubes will draw liquids to greater heights. For example, water typically rises by several centimetres in sub-millimetre diameter tubes. A short numerical example can illustrate this: for water with $\gamma \approx 0.072 \, \text{N m}^{-1} $ and $ \rho \approx 1000 \, \text{kg m}^{-3} $ in a tube of radius $ r \approx 0.2 \, \text{mm} $ (assuming perfect wetting), the rise height $ h $ would be approximately $ 7.3 \, \text{cm}$. This centimetre-scale rise is consistent with physical observations.

⚠️ Exam Alert! The lecturer explicitly stated: "This is not unlike questions have been asked in multiple choice tests." Students should be prepared to calculate capillary rise $h$ given parameters such as tube radius $r$, surface tension $\gamma$, liquid density $\rho$, and contact angle $\theta$ (if applicable).

# 9) Consolidation: linking micro, meso, and macro for liquids

This lecture established a comprehensive understanding of liquids by connecting their microscopic structure to macroscopic properties. Structurally, liquids possess strong short-range order, quantified by a distinct first coordination shell in the radial distribution function $g(r)$, but they lack the long-range periodicity characteristic of crystalline solids. This is reflected in coordination numbers, where liquids typically have $n \approx 10$ compared to $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.

Energetically, surface tension ($\gamma$) is defined macroscopically as the work required to create unit surface area ($dW = \gamma dA$) and arises microscopically from the "missing bonds" at the surface, leading to the approximation $\gamma \approx \frac{n\varepsilon}{4a_0^2}$. Consistency in problem-solving is demonstrated by showing that independent estimates of the bond energy per pair ($\varepsilon$) derived from both the latent heat of vaporisation ($L_v$) and surface tension ($\gamma$) agree to within factors of order unity, for example, in liquid nitrogen.

Finally, at the macroscopic level, curved liquid interfaces support a Laplace pressure jump of $\Delta P = \frac{2\gamma}{r}$. This pressure difference, when balanced against the hydrostatic weight of a liquid column, explains capillary rise, where $\rho g h = \frac{2\gamma \cos\theta}{r}$. This quantitative model highlights that narrower tubes result in higher liquid columns and that the wettability of the surface, expressed through the contact angle $\theta$, is a critical factor.

Key takeaways

Liquids are incompressible due to steep short-range repulsion and non-rigid due to attractive forces too weak to lock atoms into fixed positions. Their defining characteristic is that molecular kinetic energies are comparable to binding energies, confining them to a relatively narrow temperature range. Liquids exhibit strong short-range order, with typically $n \approx 10$ nearest neighbours, contrasting with the $n = 12$ of close-packed solids and the long-range order of crystalline materials. The radial distribution function $g(r)$ quantifies this structure, showing a strong first peak and damped oscillations for liquids, sharp discrete peaks for solids, and a flat distribution for ideal gases.

Surface tension $\gamma$ is the work required to create unit surface area ($dW = \gamma dA$), explained by a stretched-film model yielding $F = 2\gamma l$. Microscopically, it arises from "missing bonds" at the surface, approximated by $\gamma \approx \frac{n\varepsilon}{4a_0^2}$. The bond energy $\varepsilon$ can be independently estimated from latent heat of vaporisation ($L_v$) using $\varepsilon \approx \frac{2L_v}{N_A n}$ and from $\gamma$, with consistent results for materials like liquid nitrogen.

Capillary action, driven by surface tension, is crucial in phenomena from "tears of wine" to biological fluid transport. Wettability, measured by the contact angle $\theta$, determines how liquids interact with surfaces. Curved interfaces sustain a Laplace pressure jump $\Delta P = \frac{2\gamma}{r}$, which, when balanced by hydrostatic pressure, explains capillary rise: $\rho g h = \frac{2\gamma \cos\theta}{r}$. This demonstrates that narrower tubes achieve higher rises and that wettability significantly influences the phenomenon.

## Lecture 13: Liquids - structure, surface tension, and capillarity

The course now shifts focus from classical thermodynamics to the properties of specific states of matter, beginning with liquids. The previous block of lectures covered thermodynamic cycles, including the Carnot and Stirling cycles, and introduced fundamental concepts like entropy and the Second Law. These tools for understanding energy and temperature will continue to be relevant. Today's lecture will build a structural picture of liquids, define macroscopic surface tension and link it to microscopic bond energy, and then explore capillary action with simple quantitative models.

## # 1) What is a liquid? Macroscopic properties and energy balance

Liquids are characterised by distinct physical properties. They are largely incompressible, a characteristic stemming from the steep short-range repulsive forces that prevent molecules from being squeezed much closer together. However, unlike solids, liquids are not rigid; the attractive forces between molecules are not strong enough to lock them into fixed positions, allowing molecules to flow past one another. Liquids also exhibit viscosity, which is significantly higher than that of a gas, indicating resistance to shear.

The liquid state is defined by a delicate energy balance where the molecular kinetic energies are comparable to the bonding energies. If kinetic energies are much larger than bonding energies, molecules move freely, dominating over cohesive forces, resulting in a gas. Conversely, if kinetic energies are much smaller than bonding energies, atoms vibrate about fixed positions within a rigid structure, forming a solid. This comparable energy balance in liquids means molecules are mobile but still cohesive. This specific energetic condition explains why liquids typically exist over a relatively narrow temperature range; even small changes in temperature can tip the balance towards either the gaseous or solid phase.

## # 2) Nearest neighbours and structural order: liquids vs solids

The structure of liquids can be distinguished from solids by examining their local atomic arrangements, particularly the number of nearest neighbours and the extent of long-range order. The number of nearest neighbours, or coordination number ($n$), refers to the number of atoms in direct contact with a central atom. For a typical liquid, the average coordination number is approximately $n \approx 10$ in three dimensions. This contrasts with close-packed crystalline solids, such as face-centred cubic (FCC) or hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structures, where each atom has $n = 12$ nearest neighbours. This close packing can be visualised as stacking cannonballs in a hexagonal array.

Crystalline solids exhibit long-range order, meaning they possess a periodic, repeating arrangement where every atom "sees" an identical local environment. In contrast, liquids only exhibit short-range order; local arrangements vary from atom to atom, and periodicity is lost over larger distances. It is worth noting that some solids, such as glass, are amorphous and lack long-range order, resembling the short-range order found in liquids.

## # 3) The radial distribution function g(r): measuring structure quantitatively

The radial distribution function, $g(r)$, quantitatively describes the structural order within a material by indicating the probability of finding a particle at a given distance $r$ from a reference particle. It is defined as the ratio of the local number density $n(r)$ at distance $r$ to the average number density $n_0$ of the system: $g(r) = n(r)/n_0$. The local number density $n(r)$ is given by $n(r) = N(r)/(4\pi r^2 dr)$, where $N(r)$ is the number of molecules whose centres lie within a spherical shell of thickness $dr$ at distance $r$.

The qualitative signatures of $g(r)$ vary distinctly for different phases of matter. For liquids, $g(r)$ typically shows a pronounced first peak corresponding to the nearest neighbours, reflecting the short-range order. Subsequent peaks are broader and weaker, progressively damping out until $g(r)$ approaches 1 at large distances, indicating the loss of long-range order. In contrast, a crystalline solid would exhibit sharp, discrete peaks at fixed $r$ values, characteristic of its long-range periodic structure. An ideal gas, with no intermolecular interactions, would show $g(r) = 1$ for all $r$, as all separations are equally likely. A real gas, with weak short-range interactions, would appear mostly flat but might show a slight initial peak at very short distances. Plots for liquid water and argon, for instance, both show strong first peaks, but water's hydrogen-bond network results in a sharper and slightly shifted first shell compared to simple liquids like argon.

## # 4) Surface tension γ: macroscopic definition and a simple film model

Surface tension ($\gamma$) is a macroscopic property of liquids, defined as the work required to create a unit of surface area. This relationship is expressed as $dW = \gamma dA$. This intrinsic tension explains why liquid droplets tend to adopt a spherical shape, as a sphere minimises surface area for a given volume, thereby minimising the total surface energy.

The concept of surface tension can be illustrated through a stretched liquid film. Consider a thin liquid film of width $l$ that is stretched by an infinitesimal distance $dx$. Since the film has two surfaces (a top and a bottom), the total increase in surface area is $2l\,dx$. The work done by the pulling force $F$ over the distance $dx$ must equal this increase in surface energy: $F\,dx = \gamma (2l\,dx)$. This derivation leads to the relationship $F = 2\gamma l$. This equation confirms that surface tension has dimensions of energy per unit area (e.g., $\text{J m}^{-2}$) or, equivalently, force per unit length (e.g., $\text{N m}^{-1}$).

## # 5) Microscopic link: from γ to bond energy ε and back to L_v

The macroscopic phenomenon of surface tension can be linked to the microscopic bond energy ($\varepsilon$) by considering the "missing bonds" at a liquid's surface. Molecules at the surface have fewer neighbours compared to those in the bulk, resulting in a higher potential energy. Approximating the energy associated with these missing bonds, the surface energy per unit area ($\gamma$) scales with the bond energy per molecule ($\varepsilon/2$, to avoid double counting), the fraction of missing neighbours (approximately $n/2$), and the surface number density (approximately $1/a_0^2$, where $a_0$ is the atomic spacing). This leads to the approximate relationship: $\gamma \approx \frac{n\varepsilon}{4a_0^2}$.

This microscopic model of surface tension can be cross-linked with earlier macroscopic measures of bond energy. From previous derivations related to the latent heat of vaporisation ($L_v$), the bond energy per pair was approximated as $\varepsilon \approx \frac{2L_v}{N_A n}$, where $N_A$ is Avogadro's number and $n$ is the coordination number. Combining these two expressions for $\varepsilon$ yields a relationship between surface tension and latent heat: $\gamma = \frac{L_v}{2N_A a_0^2}$.

A worked example for liquid nitrogen demonstrates the consistency of these independent approaches. Given a surface tension of $\gamma \approx 4 \times 10^{-3}\,\text{N m}^{-1}$, a density of $\rho \approx 800\,\text{kg m}^{-3}$, a latent heat of vaporisation $L_v \approx 5.6\,\text{kJ mol}^{-1}$, and a coordination number $n \approx 10$, the atomic spacing $a_0$ can be estimated from the density and molecular size. Using these values, the bond energy calculated from $L_v$ is approximately $\varepsilon \approx 0.012\,\text{eV}$, while the calculation from $\gamma$ yields $\varepsilon \approx 0.016\,\text{eV}$. The agreement between these two independently derived, albeit crude, estimates within factors of order unity provides validation for the underlying physical models.

## # 6) Capillarity in the world: where surface tension matters

Surface tension plays a crucial role in numerous everyday phenomena and technological applications, a collective set of effects often termed capillarity. Examples include the formation of "tears of wine" on a glass, where differential surface tensions between alcohol and water drive fluid flows. In sandcastles, the surface tension of water binds individual sand grains, allowing them to form cohesive structures. Candles rely on capillary action to draw molten wax up the wick, where it then vaporises and burns; the wick acts as a transporter, not the primary fuel. Biologically, capillary networks in living organisms depend on surface tension and wetting properties for fluid transport.

The interaction between a liquid and a solid surface is described by its wettability, quantified by the contact angle ($\theta$). Wettability depends on the balance between adhesion (liquid-solid attraction) and cohesion (liquid-liquid attraction). For instance, water on clean glass exhibits excellent wetting with a contact angle of $\theta \approx 0^\circ$. In contrast, mercury on glass shows poor wetting, forming near-spherical droplets with a large contact angle. Typical surface tension values highlight this difference: water has $\gamma_{\text{water}} \approx 0.072\,\text{N m}^{-1}$, while mercury has a much higher $\gamma_{\text{mercury}} \approx 0.465\,\text{N m}^{-1}$.

## # 7) Quantifying curvature: pressure jump across a curved surface

A curved liquid-vapour interface experiences a pressure difference across it, a phenomenon quantified by the Laplace pressure. This can be understood through a thought experiment involving a vapour bubble (internal pressure $P_1$) within a liquid (external pressure $P_2$). If the bubble's radius increases by an infinitesimal amount $dr$, the work done by the pressure difference $(P_1 - P_2)$ to expand its volume must be balanced by the increase in the bubble's surface energy.

The increase in surface area for a spherical bubble of radius $r$ when expanded by $dr$ is approximately $8\pi r\,dr$. The work done by the pressure difference is $(P_1 - P_2) dV$, where $dV = 4\pi r^2 dr$. Equating the work done to the increase in surface energy ($\gamma \times \text{area increase}$) leads to the Laplace pressure equation for a spherical interface: $(P_1 - P_2) = \frac{2\gamma}{r}$. This relationship indicates that higher curvature (smaller radius $r$) requires a larger pressure difference to sustain the interface. Physically, smaller bubbles possess higher internal pressure compared to larger ones due to the greater curvature.

## # 8) Capillary rise: balancing surface forces with hydrostatic weight

When a narrow tube is placed in a liquid, surface tension causes the liquid inside the tube to form a curved meniscus. This curved surface results in a lower pressure just beneath the meniscus inside the tube compared to the flat liquid surface in the reservoir outside. This pressure difference then supports a column of liquid of height $h$, which is balanced by the hydrostatic head of the liquid column.

The height of capillary rise can be derived via two equivalent routes. The pressure-based route equates the hydrostatic pressure of the liquid column to the Laplace pressure across the meniscus: $\rho g h = \frac{2\gamma}{r}$, assuming perfect wetting ($\theta = 0^\circ$). The force-based route balances the upward force due to surface tension along the circumference of the meniscus ($2\pi r \gamma$) with the downward gravitational force (weight) of the liquid column ($\pi r^2 h \rho g$), yielding the same result. For partial wetting, the more general formula is $\rho g h = \frac{2\gamma \cos\theta}{r}$.

This relationship reveals that the capillary rise height $h$ is inversely proportional to the tube's radius $r$; finer tubes will draw liquids to greater heights. For example, water typically rises by several centimetres in sub-millimetre diameter tubes. A short numerical example can illustrate this: for water with $\gamma \approx 0.072\,\text{N m}^{-1}$ and $\rho \approx 1000\,\text{kg m}^{-3}$ in a tube of radius $r \approx 0.2\,\text{mm}$ (assuming perfect wetting), the rise height $h$ would be approximately $7.3\,\text{cm}$. This centimetre-scale rise is consistent with physical observations.

> **⚠️ Exam Alert!** The lecturer explicitly stated: "This is not unlike questions have been asked in multiple choice tests." Students should be prepared to calculate capillary rise $h$ given parameters such as tube radius $r$, surface tension $\gamma$, liquid density $\rho$, and contact angle $\theta$ (if applicable).

## # 9) Consolidation: linking micro, meso, and macro for liquids

This lecture established a comprehensive understanding of liquids by connecting their microscopic structure to macroscopic properties. Structurally, liquids possess strong short-range order, quantified by a distinct first coordination shell in the radial distribution function $g(r)$, but they lack the long-range periodicity characteristic of crystalline solids. This is reflected in coordination numbers, where liquids typically have $n \approx 10$ compared to $n = 12$ for close-packed solids.

Energetically, surface tension ($\gamma$) is defined macroscopically as the work required to create unit surface area ($dW = \gamma dA$) and arises microscopically from the "missing bonds" at the surface, leading to the approximation $\gamma \approx \frac{n\varepsilon}{4a_0^2}$. Consistency in problem-solving is demonstrated by showing that independent estimates of the bond energy per pair ($\varepsilon$) derived from both the latent heat of vaporisation ($L_v$) and surface tension ($\gamma$) agree to within factors of order unity, for example, in liquid nitrogen.

Finally, at the macroscopic level, curved liquid interfaces support a Laplace pressure jump of $\Delta P = \frac{2\gamma}{r}$. This pressure difference, when balanced against the hydrostatic weight of a liquid column, explains capillary rise, where $\rho g h = \frac{2\gamma \cos\theta}{r}$. This quantitative model highlights that narrower tubes result in higher liquid columns and that the wettability of the surface, expressed through the contact angle $\theta$, is a critical factor.

## Key takeaways

Liquids are incompressible due to steep short-range repulsion and non-rigid due to attractive forces too weak to lock atoms into fixed positions. Their defining characteristic is that molecular kinetic energies are comparable to binding energies, confining them to a relatively narrow temperature range. Liquids exhibit strong short-range order, with typically $n \approx 10$ nearest neighbours, contrasting with the $n = 12$ of close-packed solids and the long-range order of crystalline materials. The radial distribution function $g(r)$ quantifies this structure, showing a strong first peak and damped oscillations for liquids, sharp discrete peaks for solids, and a flat distribution for ideal gases.

Surface tension $\gamma$ is the work required to create unit surface area ($dW = \gamma dA$), explained by a stretched-film model yielding $F = 2\gamma l$. Microscopically, it arises from "missing bonds" at the surface, approximated by $\gamma \approx \frac{n\varepsilon}{4a_0^2}$. The bond energy $\varepsilon$ can be independently estimated from latent heat of vaporisation ($L_v$) using $\varepsilon \approx \frac{2L_v}{N_A n}$ and from $\gamma$, with consistent results for materials like liquid nitrogen.

Capillary action, driven by surface tension, is crucial in phenomena from "tears of wine" to biological fluid transport. Wettability, measured by the contact angle $\theta$, determines how liquids interact with surfaces. Curved interfaces sustain a Laplace pressure jump $\Delta P = \frac{2\gamma}{r}$, which, when balanced by hydrostatic pressure, explains capillary rise: $\rho g h = \frac{2\gamma \cos\theta}{r}$. This demonstrates that narrower tubes achieve higher rises and that wettability significantly influences the phenomenon.