Lecture 14: Solids and Crystals

0) Orientation, admin, and learning outcomes

The problems class scheduled for Friday has been cancelled. It will be replaced by a two-hour revision session next week, covering both Mechanics and Properties of Matter. This session will be recorded. During the revision session, the lecturer will highlight slides that are typically relevant to exam-style questions, noting that the December test consists of ten multiple-choice questions, which constrains the format of questions.

This lecture marks a transition in the course, moving from the study of thermodynamics back to the discussion of material phases, with a specific focus on solids.

Upon completion of this lecture, students should be able to define and characterise a solid, define a crystal, and recall that there are seven crystal systems and fourteen Bravais lattices (memorisation of all is not required for first year). Students should also be able to draw and describe the three cubic Bravais lattices (simple cubic, body-centred cubic, and face-centred cubic), and calculate packing fractions for these structures.

1) What is a solid? Macroscopic properties and microscopic picture

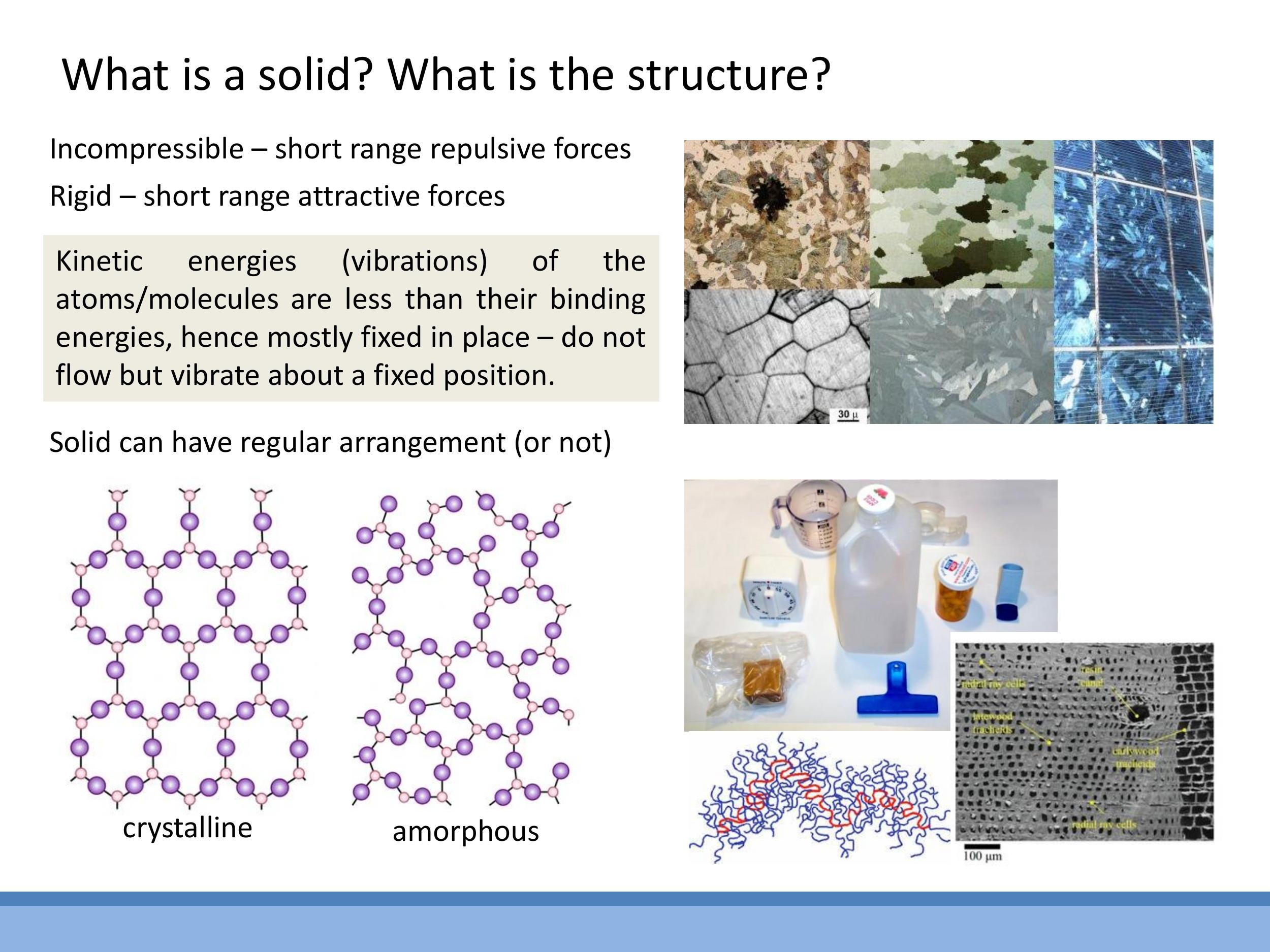

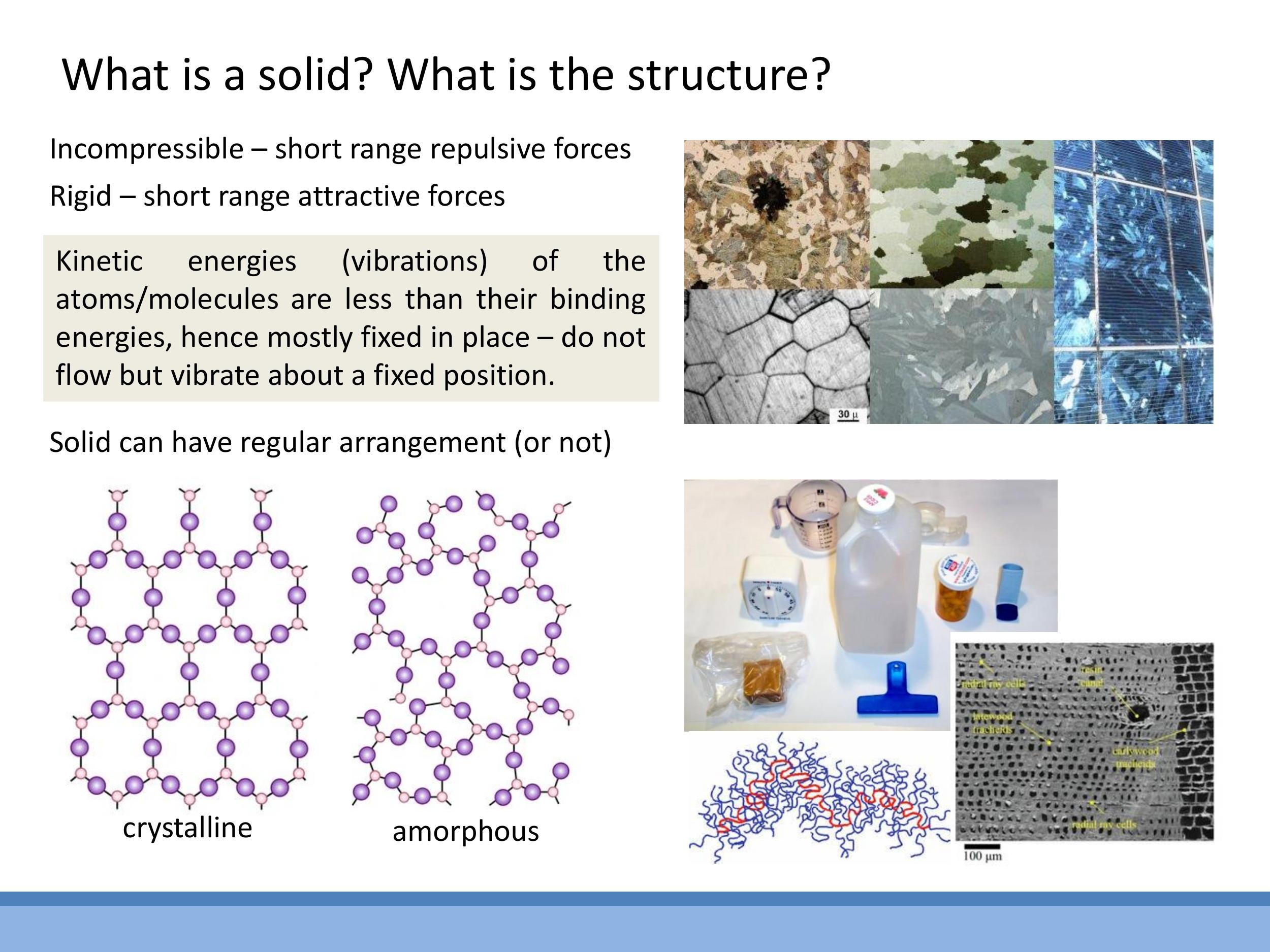

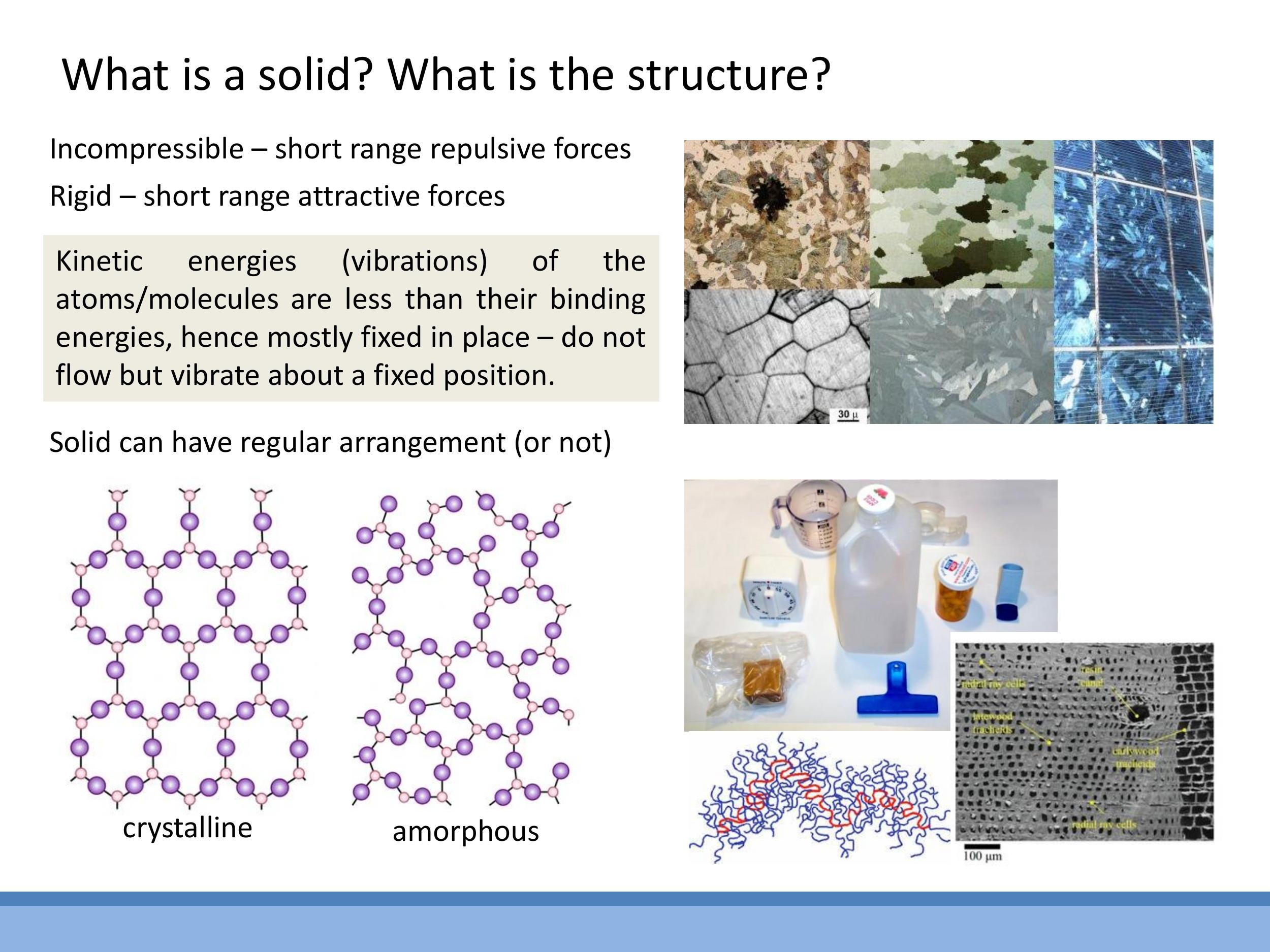

Solids are characterised by two primary macroscopic properties: incompressibility and rigidity. Incompressibility arises from steep short-range repulsive forces between atoms, making it very difficult to force them closer together. Rigidity is a result of net attractive forces that hold atoms in fixed positions, resisting shear or flow.

From a microscopic perspective, the defining behaviour of atoms in a solid is that their kinetic energies are significantly less than their binding energies. This energy imbalance means that atoms in a solid do not exhibit translational motion, preventing any flow. Instead, their kinetic energy is confined solely to vibrations about fixed equilibrium positions. This contrasts with liquids, where atomic kinetic energies are comparable to bonding energies, allowing atoms to rearrange and flow past one another.

2) Crystalline vs amorphous; grains and real materials

Solids can be broadly classified into two structural types: crystalline and amorphous. Crystalline solids possess a periodic, repeating arrangement of atoms, where each atom experiences an identical local environment. In contrast, amorphous solids have atoms fixed in position but lack long-range periodicity, resulting in a more random structure; examples include polymers, wood, and glass.

Most everyday crystalline materials are polycrystalline, meaning they are composed of many small, single-crystal regions known as grains, each with a different crystallographic orientation. A common example is the glinting observed on steel railings in sunlight, which is caused by light reflecting off these differently oriented crystallographic grains.

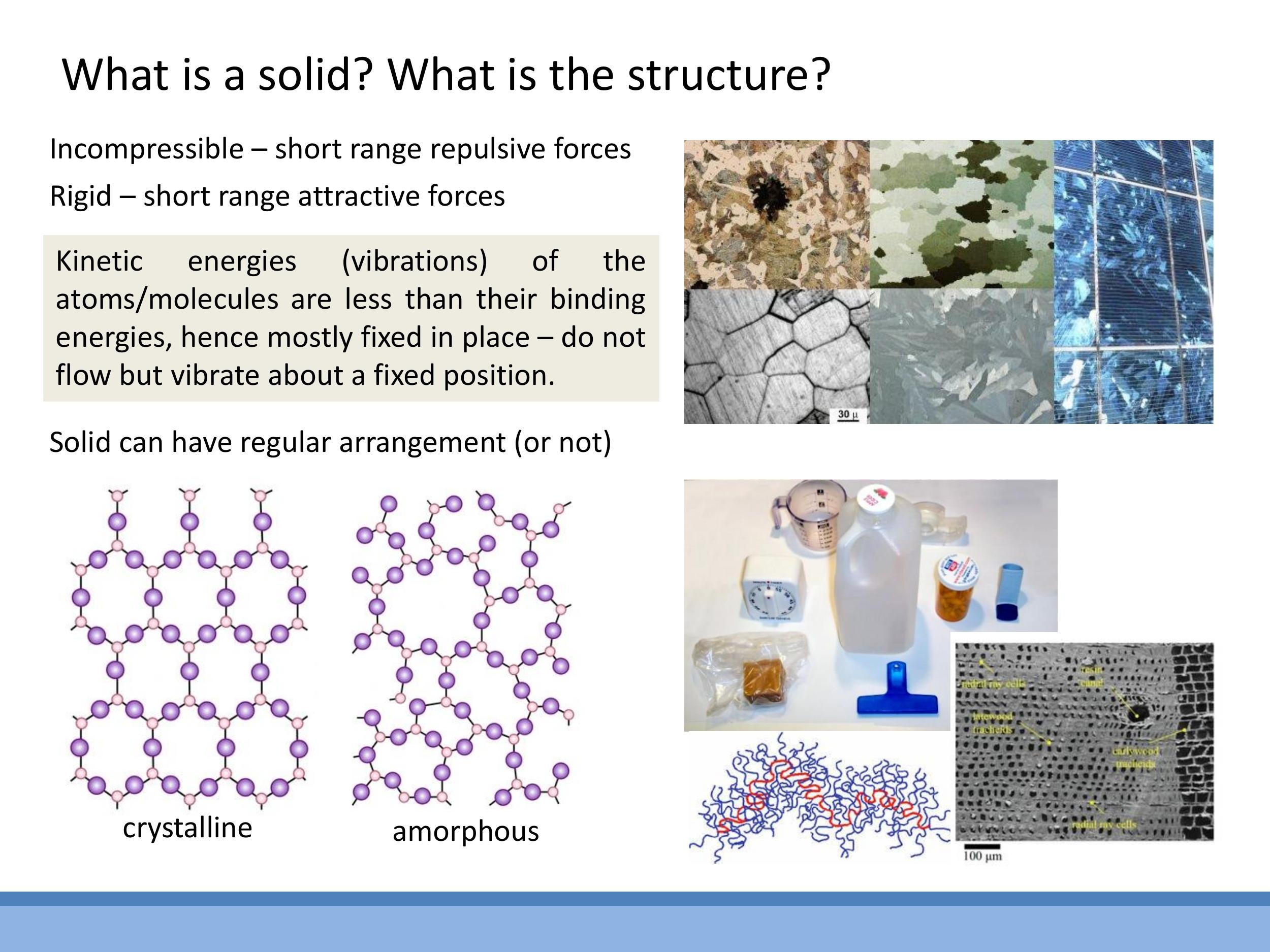

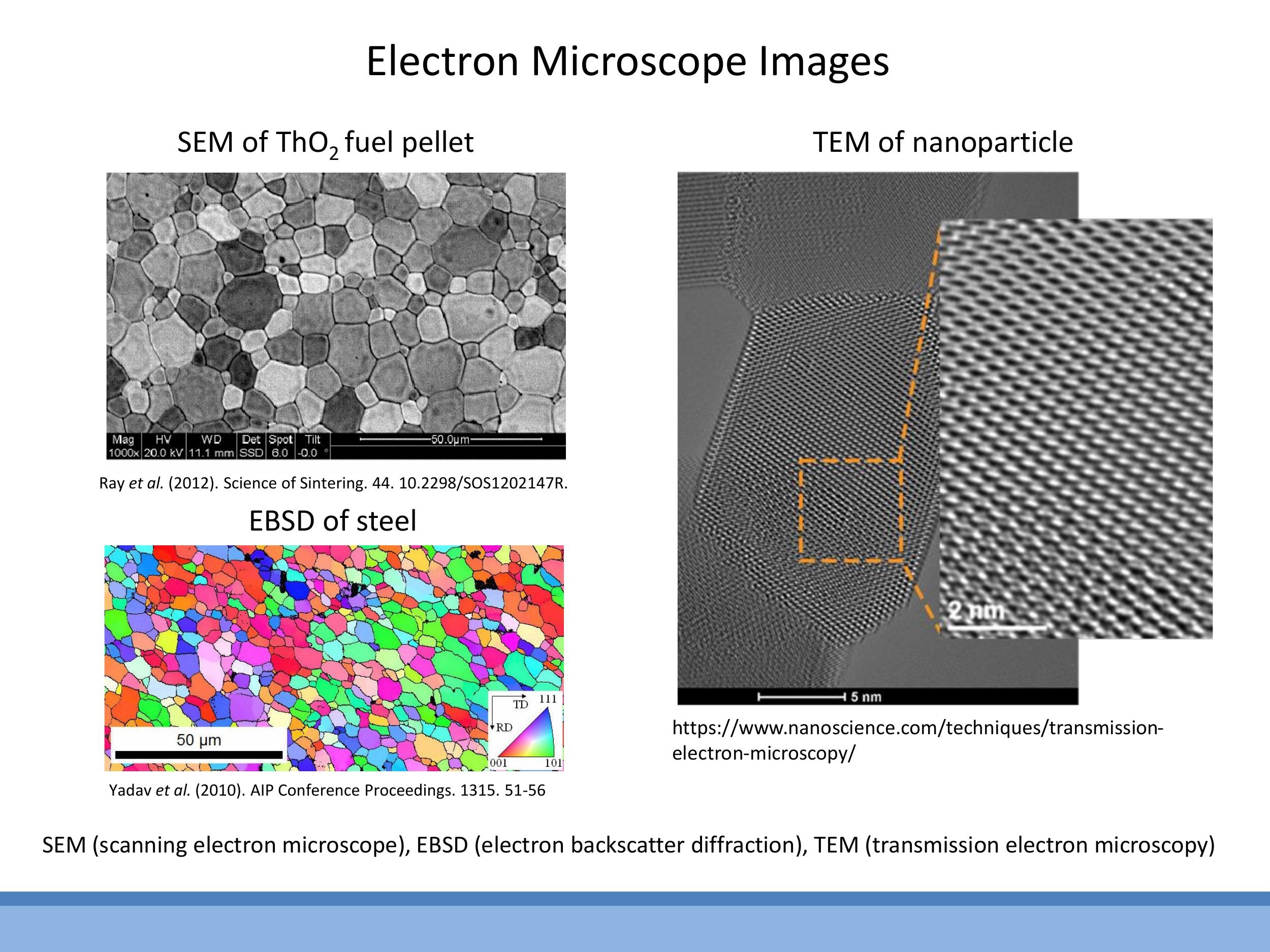

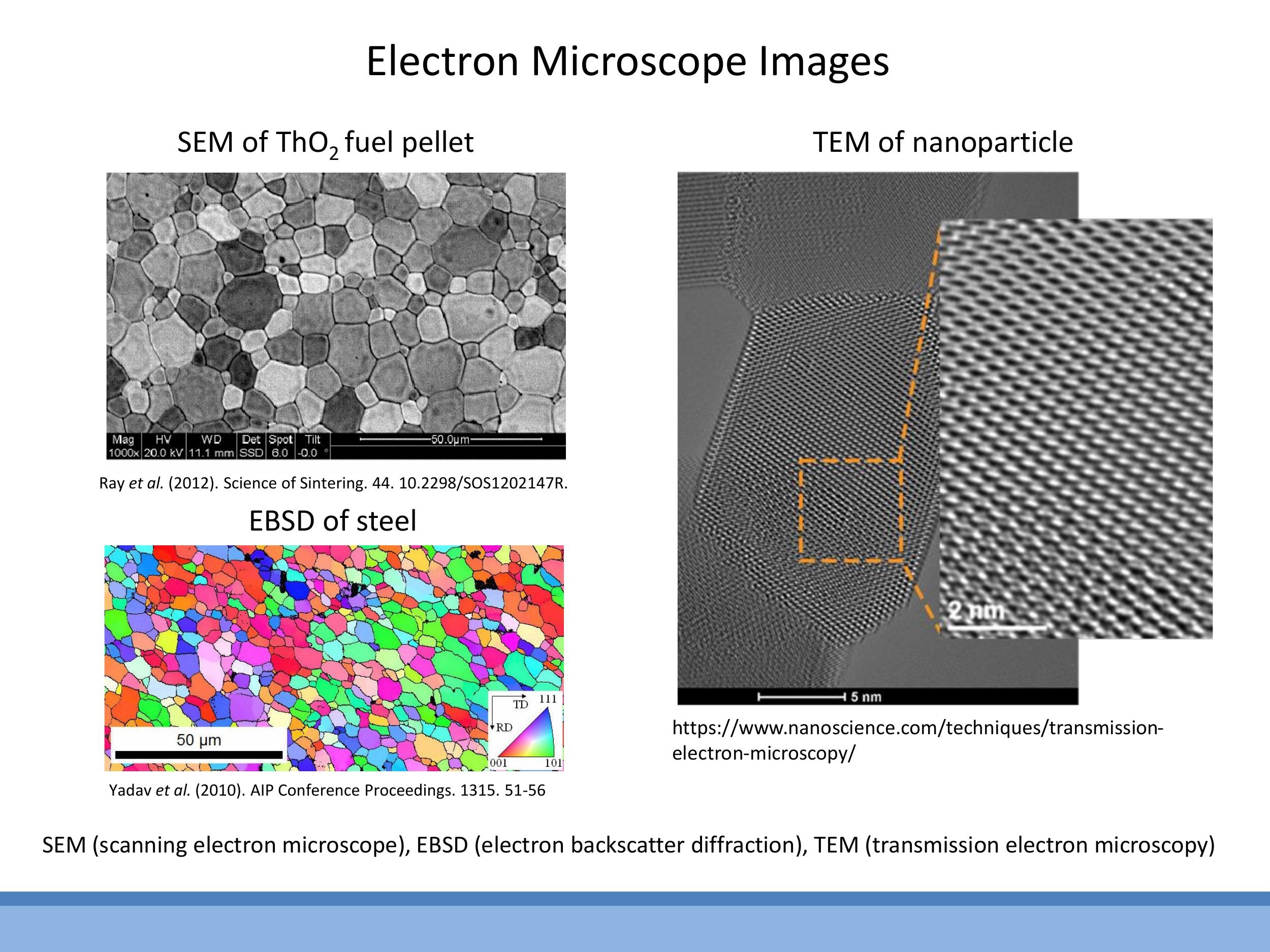

The internal structure of materials can be visualised experimentally using electron microscopy techniques. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) can reveal grains and their orientations at the micron scale. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) offers a higher resolution, capable of showing atomic rows within a single grain, providing direct evidence of the material's atomic-scale periodicity.

3) Packing atoms as spheres in 2D: from square to hexagonal

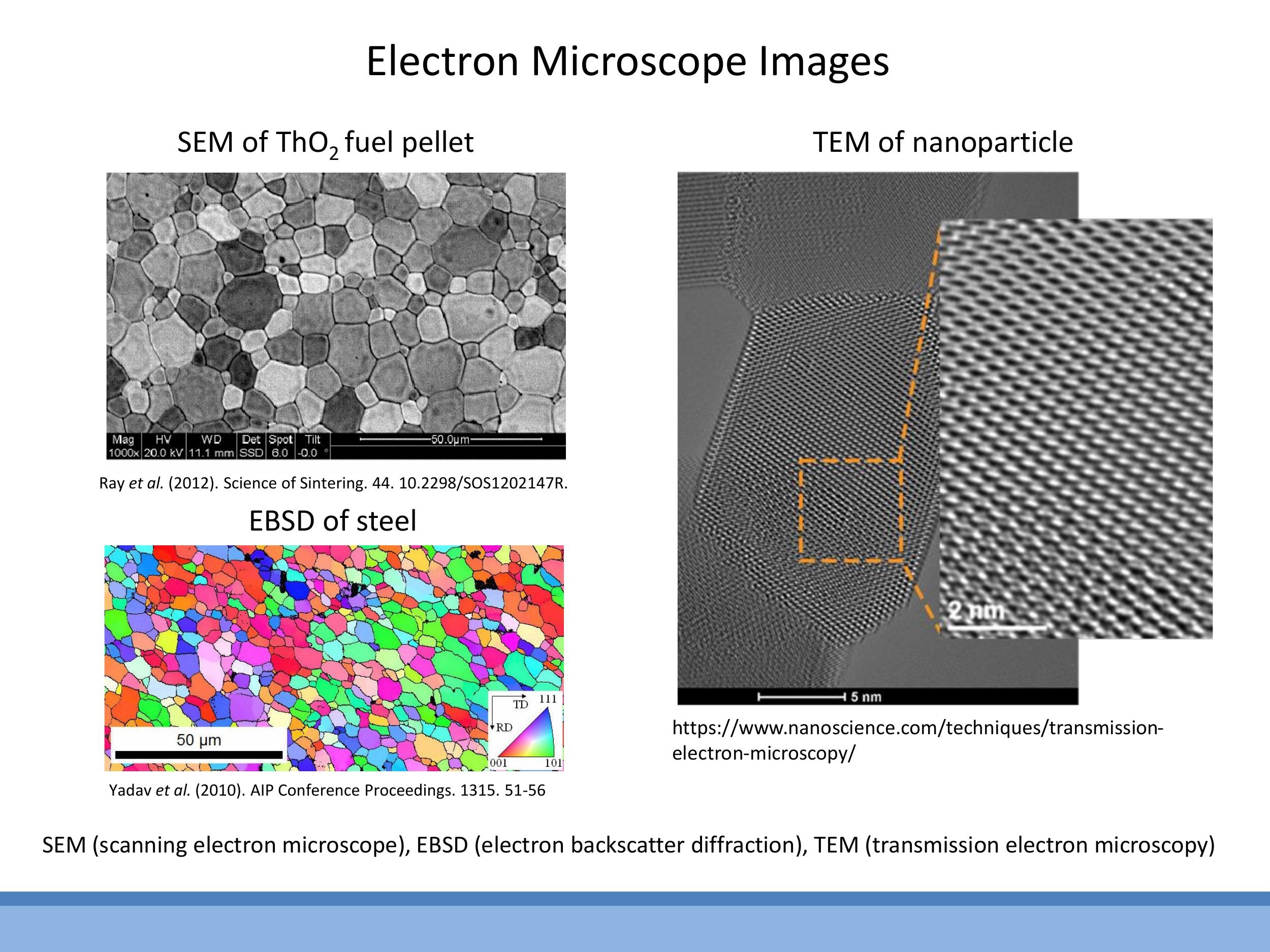

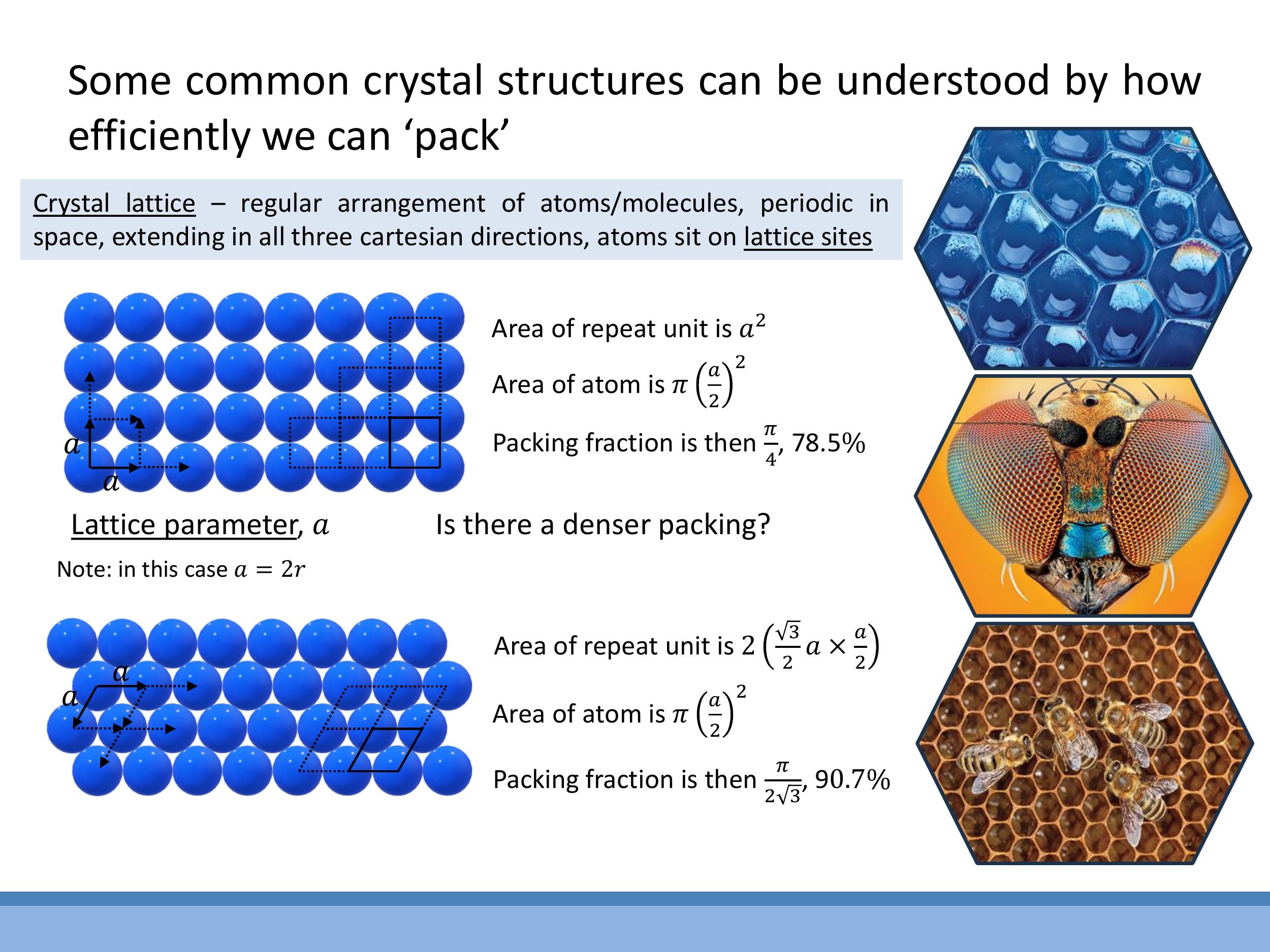

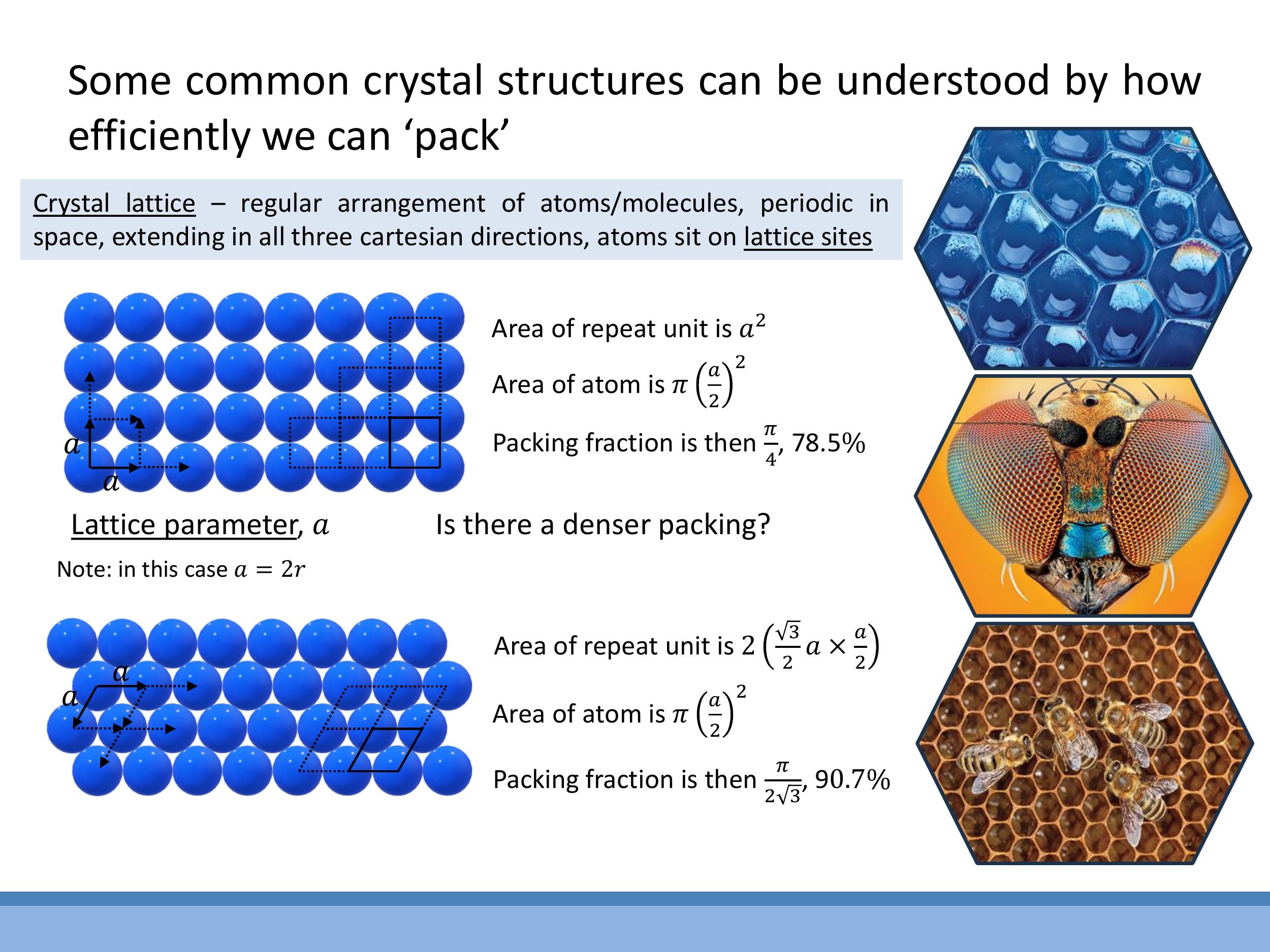

To understand crystal structures, atoms are often approximated as identical hard spheres, and their packing efficiency is investigated. The lattice parameter $a$ is defined as the repeating distance between equivalent sites in the lattice.

For a square (simple) 2D lattice, the lattice parameter $a = 2r$, where $r$ is the atomic radius. The conventional unit cell is a square containing one atom (from four quarter-atoms at the corners). The packing fraction is calculated as the area of the atom(s) within the cell divided by the area of the cell: $\frac{\pi r^2}{(2r)^2} = \frac{\pi}{4} \approx 78.5 \% $.

A denser arrangement is found in the hexagonal 2D lattice. The repeat unit for this structure is a parallelogram composed of two equilateral triangles, which still contains one atom equivalent. The packing fraction for this arrangement is $\frac{\pi r^2}{\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} (2r)^2\right)} = \frac{\pi}{2\sqrt{3}} \approx 90.7 \% $, demonstrating a significantly more efficient packing.

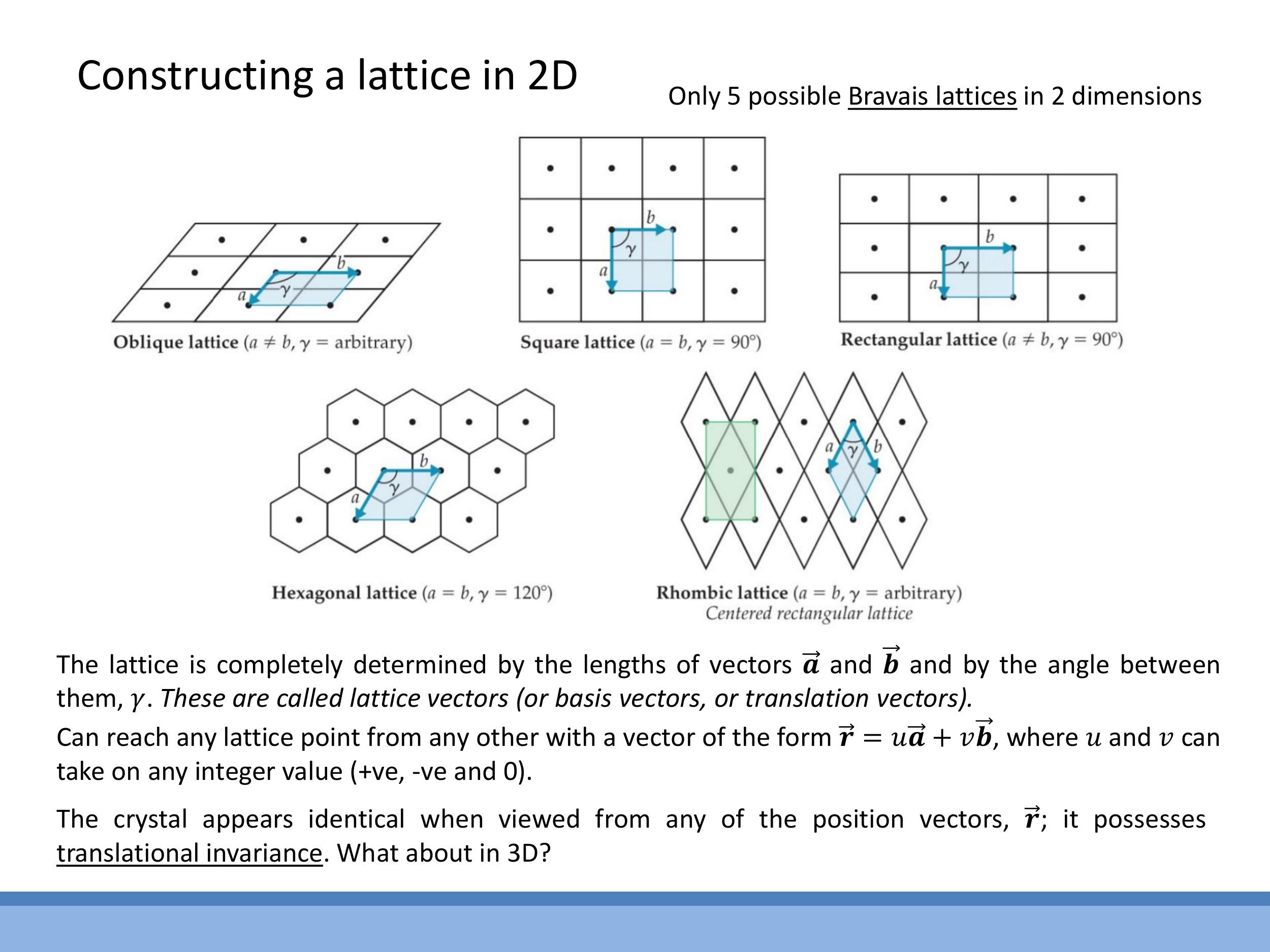

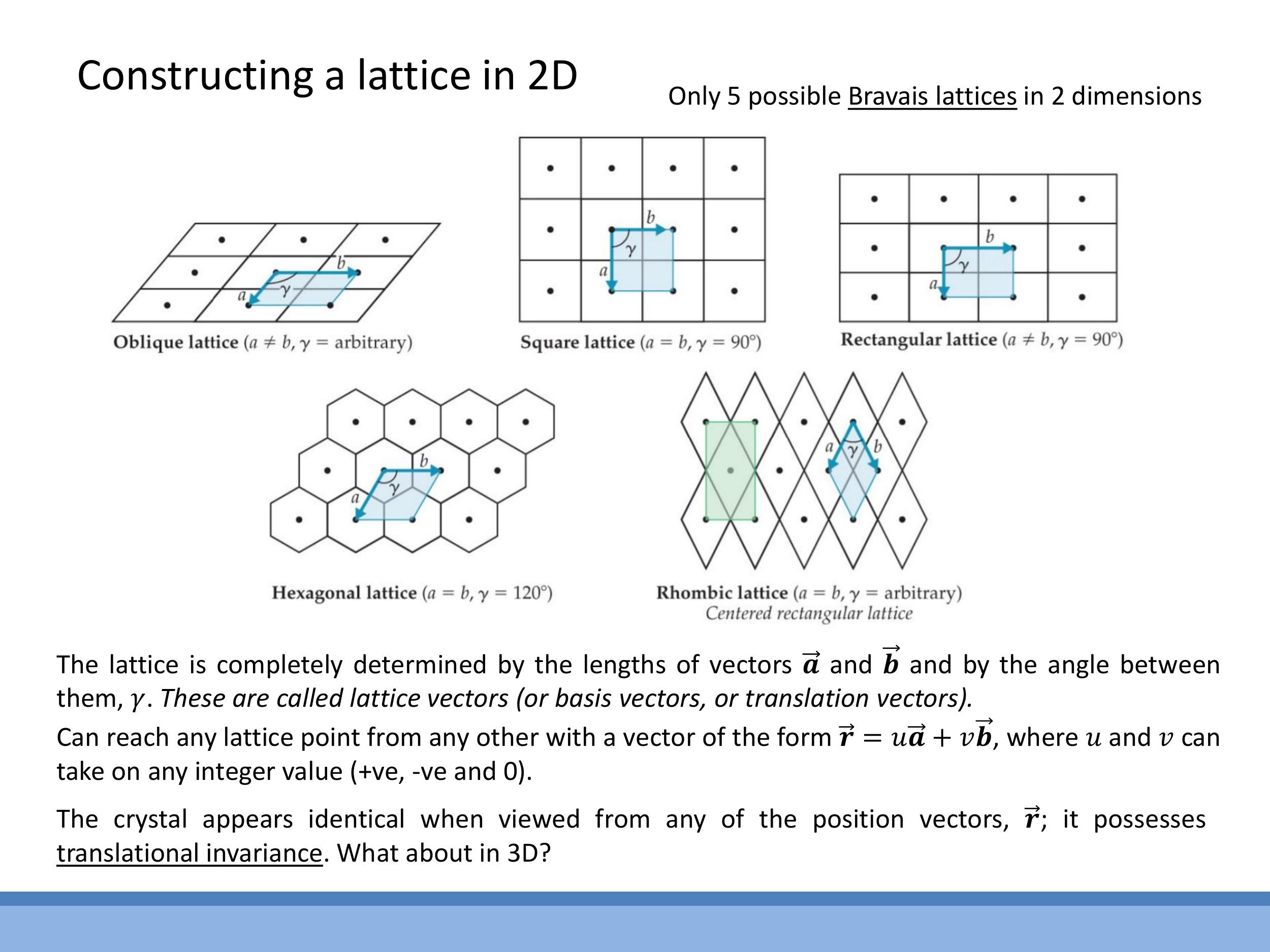

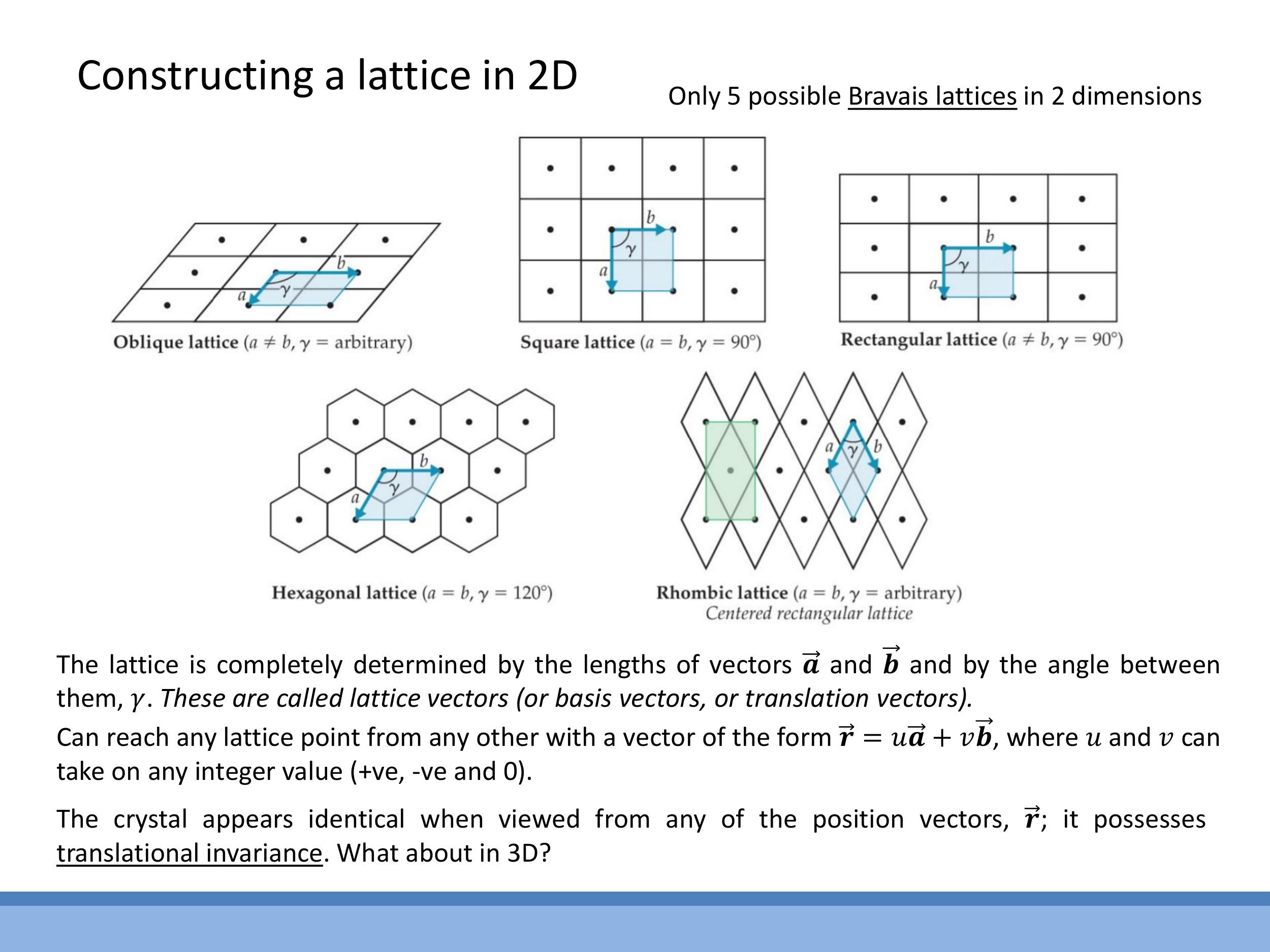

Crystal lattices exhibit translational invariance, meaning any lattice point can be reached from another by integer steps along two basis vectors, $\vec{r} = u\vec{a} + v\vec{b}$, where $u$ and $v$ are integers. In two dimensions, there are only five possible Bravais lattices that exhibit this periodicity: oblique, square, rectangular, hexagonal, and rhombic (also known as centred rectangular).

4) From 2D layers to 3D close packing: hcp and fcc

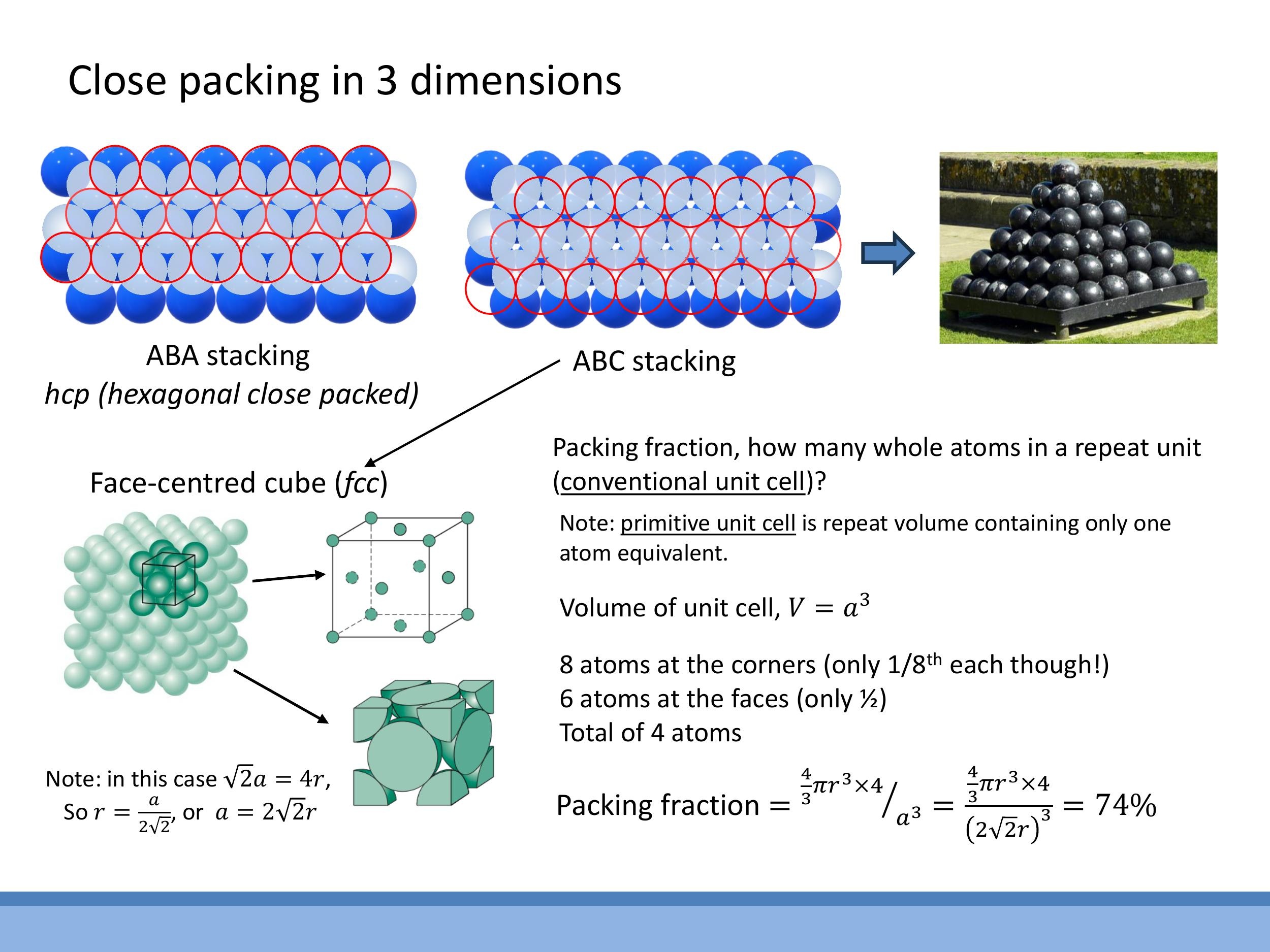

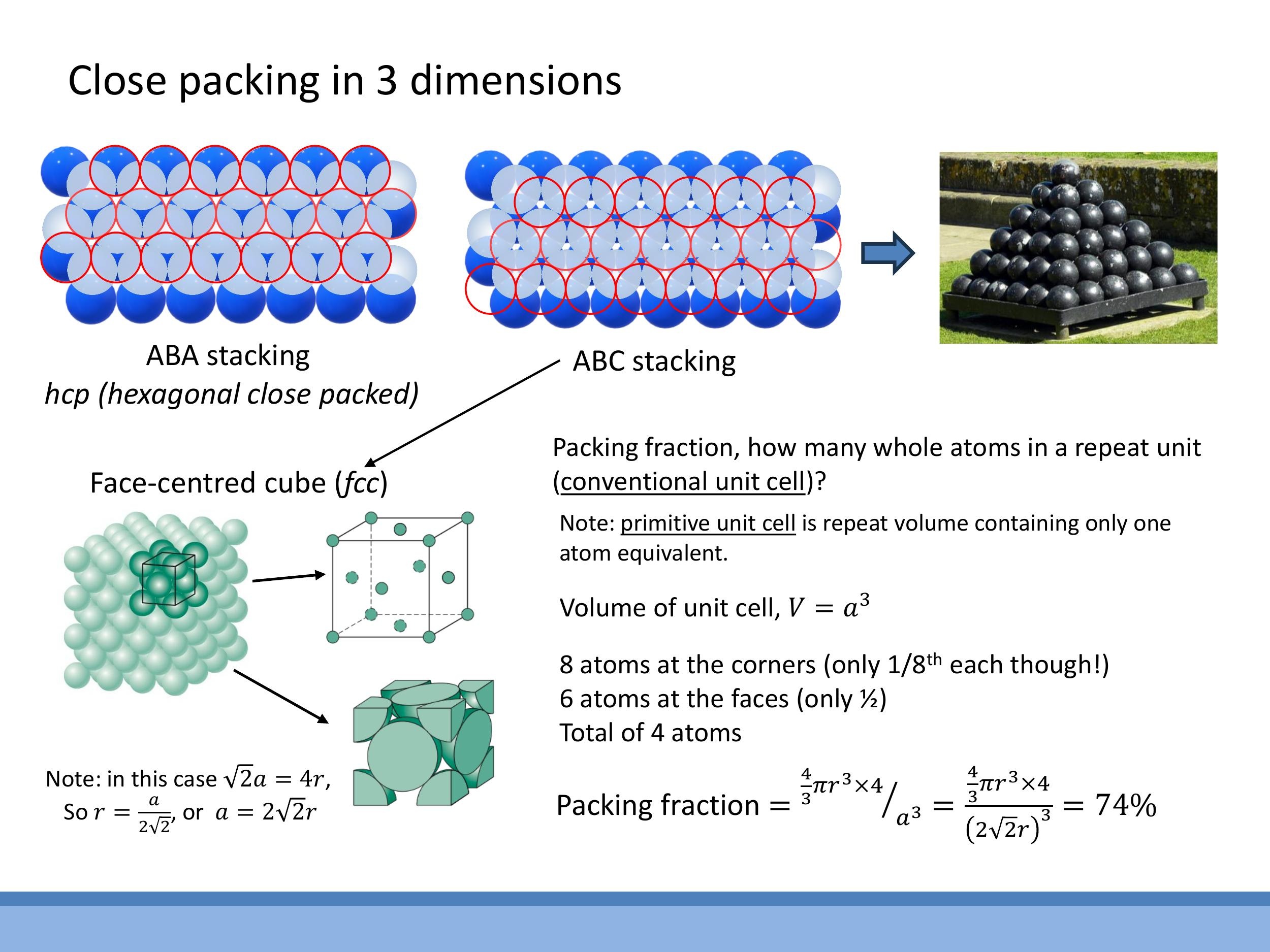

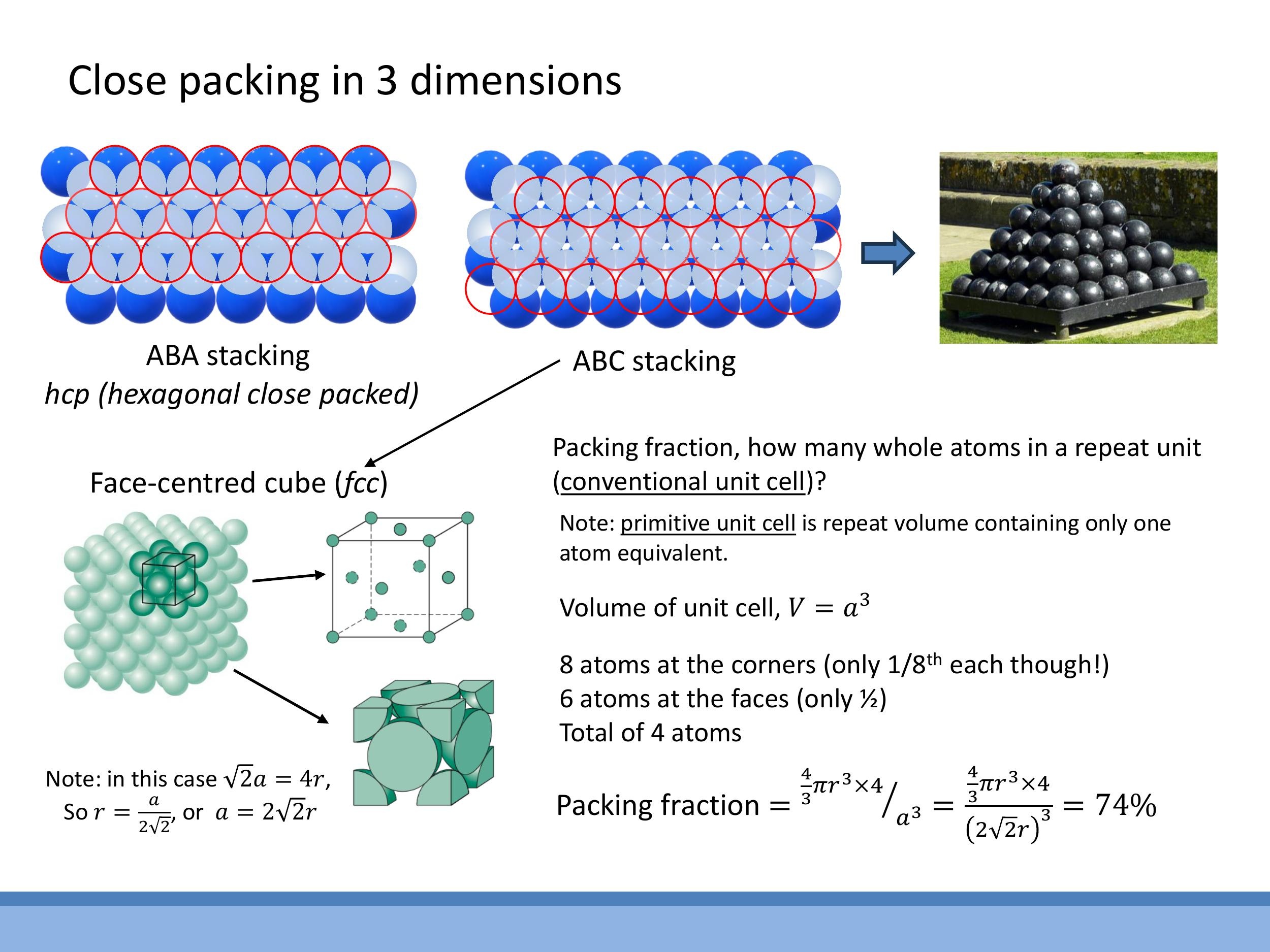

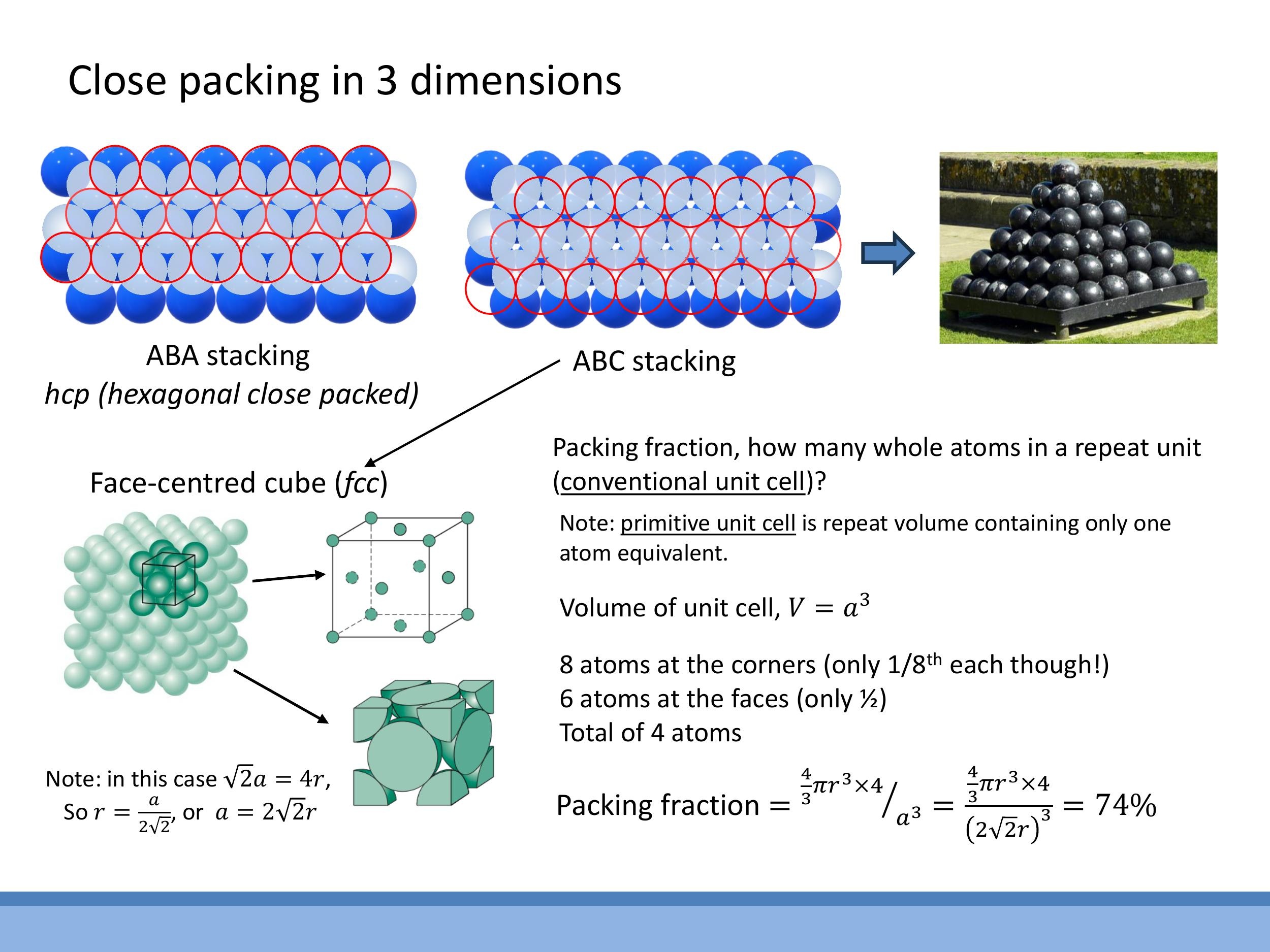

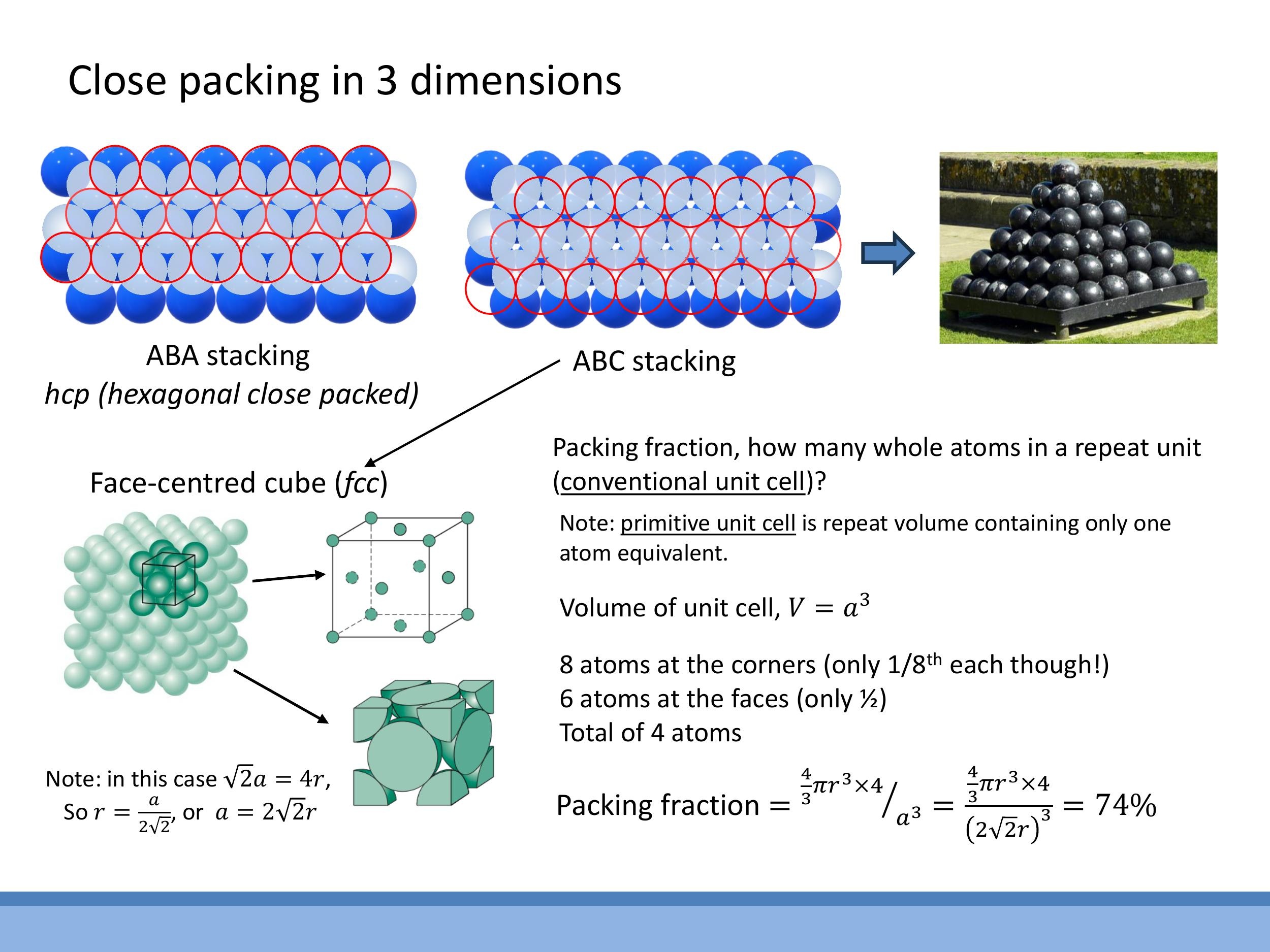

Extending the packing concept to three dimensions begins with a hexagonally packed two-dimensional layer. Subsequent layers of spheres are placed into the gaps of the layer below. This leads to two primary close-packing sequences. The ABAB... stacking sequence, where every other layer aligns directly with the first, results in a hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure. Alternatively, the ABCABC... stacking sequence, where each new layer occupies a different set of gaps from the previous two, forms a face-centred cubic (fcc) structure. Both hcp and fcc arrangements achieve the same maximum packing fraction, representing the densest possible sphere packings in three dimensions. For the purposes of this course, calculations will primarily focus on cubic structures.

5) The three cubic Bravais lattices; coordination and unit cells

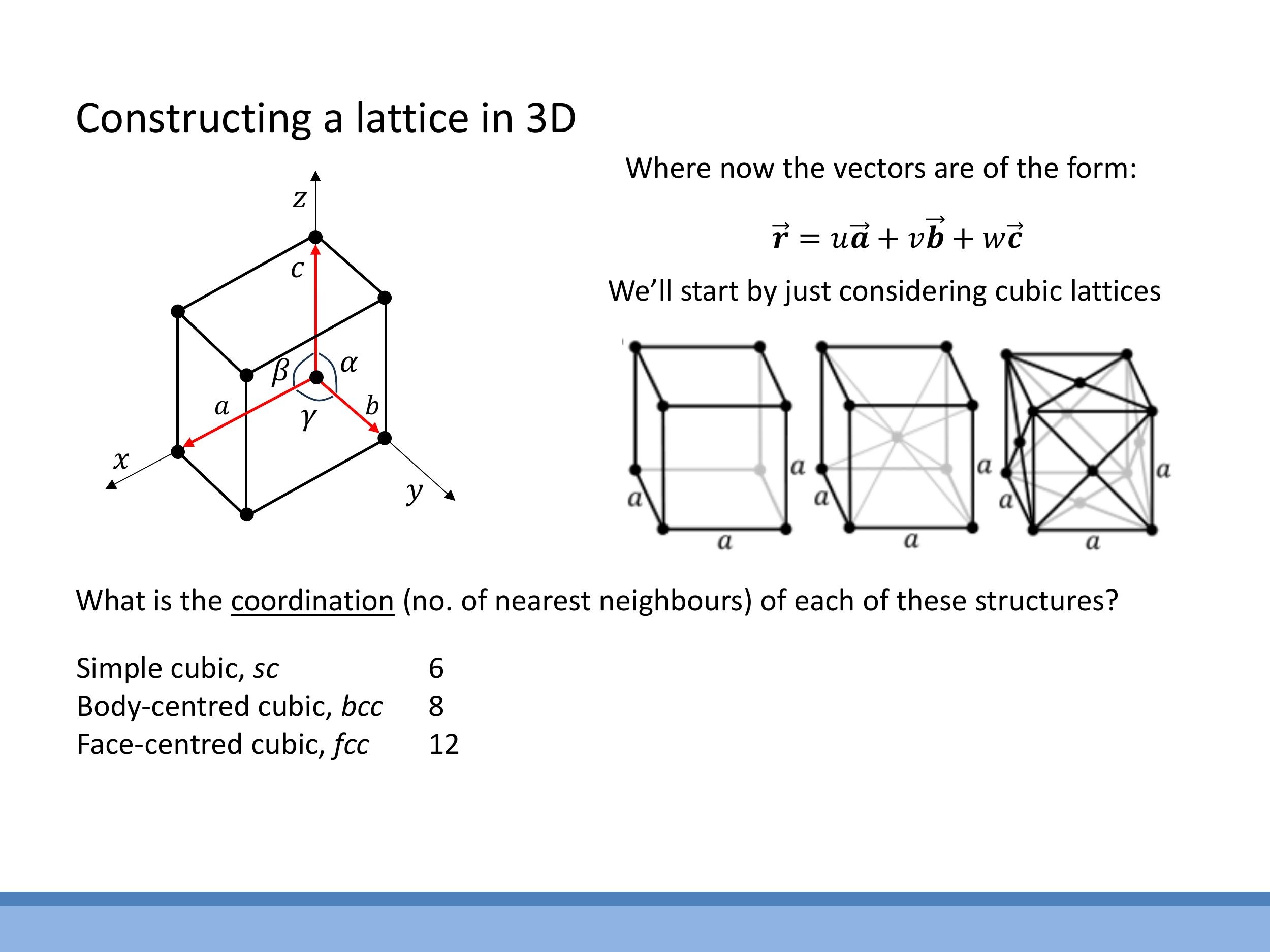

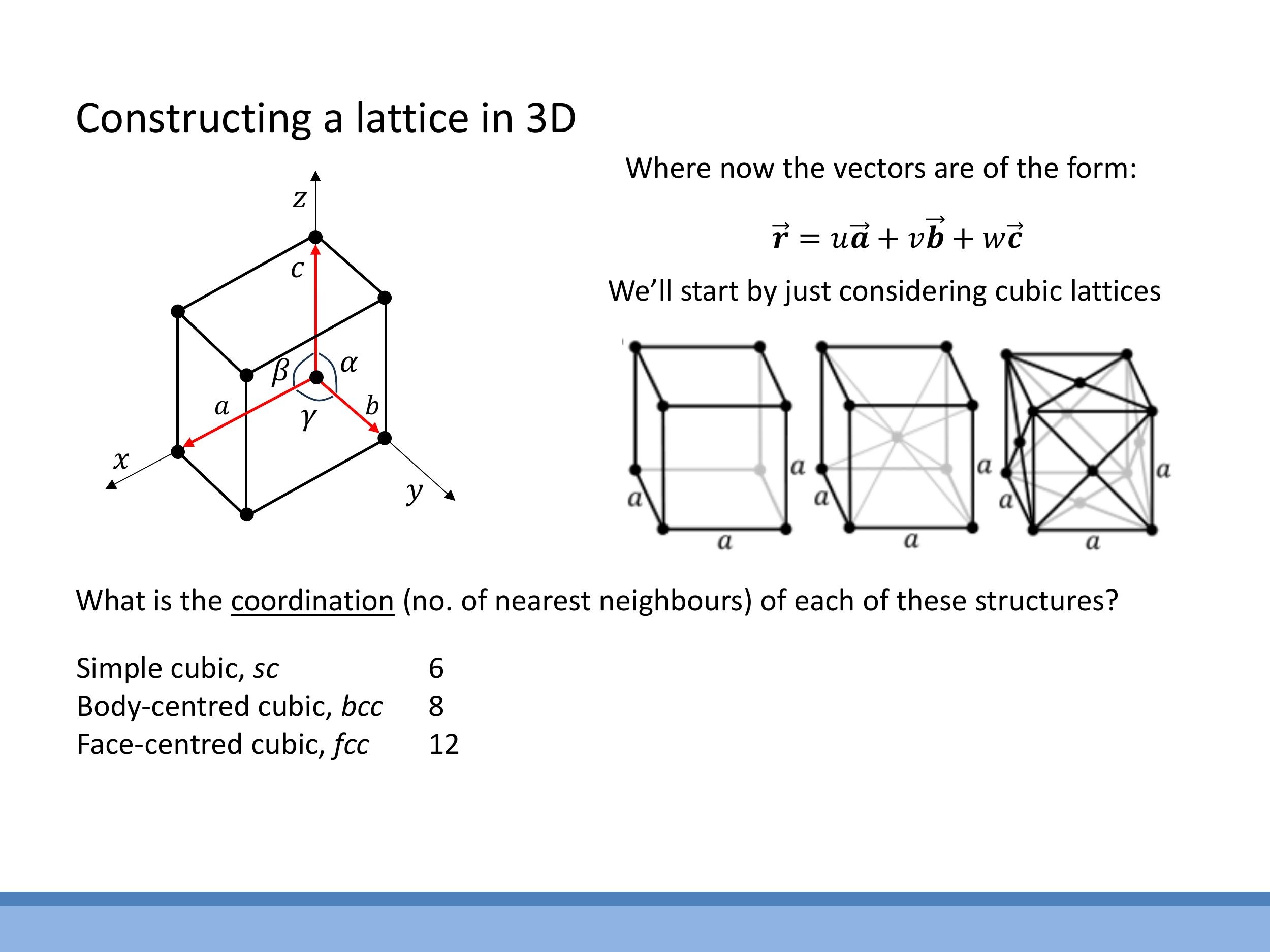

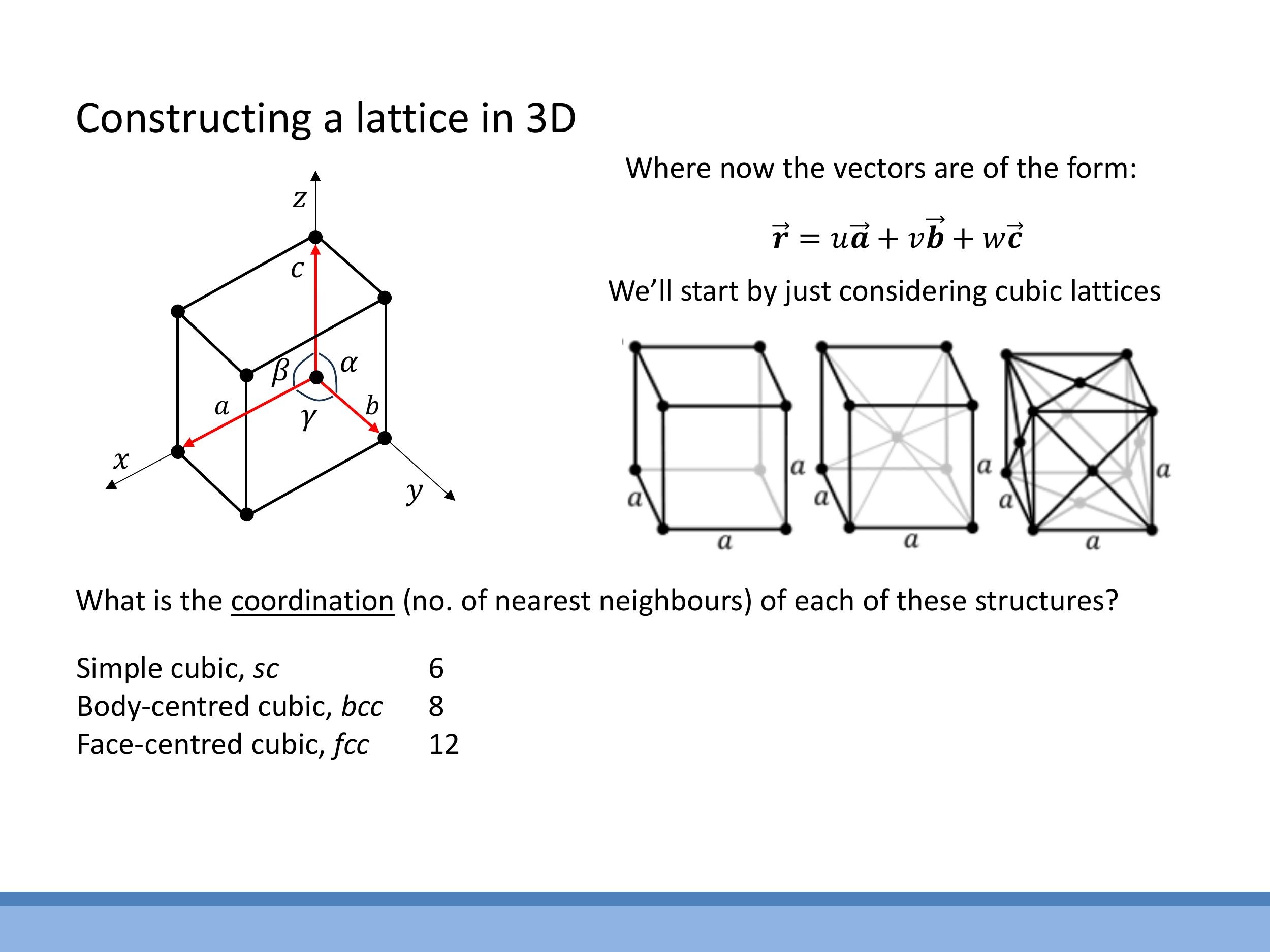

The cubic crystal system includes three distinct Bravais lattices, all defined by a conventional unit cell with an edge length $a$:

- Simple Cubic (sc): Atoms are located only at the corners of the cube. This arrangement is rare in nature due to its inefficient packing.

- Body-Centred Cubic (bcc): Atoms are found at each corner of the cube, with an additional atom situated at the exact centre of the cube (e.g., iron at certain temperatures).

- Face-Centred Cubic (fcc): Atoms are positioned at each corner of the cube and at the centre of each of the six faces (e.g., copper).

The coordination number quantifies the number of nearest neighbours surrounding a central atom in a given lattice. For simple cubic (sc) structures, the coordination number is 6. In body-centred cubic (bcc) structures, it is 8. For face-centred cubic (fcc) structures, the coordination number is 12. These numbers reflect how many nearest neighbours can geometrically fit around a central atom in each lattice type.

The conventional unit cell is the intuitively obvious cubic structure, containing atoms at corners and potentially face or body sites. In contrast, a primitive unit cell is the smallest volume that contains only one atom-equivalent. While primitive cells are fundamental, they are often less intuitive and are generally not used for describing cubic metals in this context, where the conventional cell is preferred for clarity.

6) Worked density result: fcc packing fraction ≈ 74%

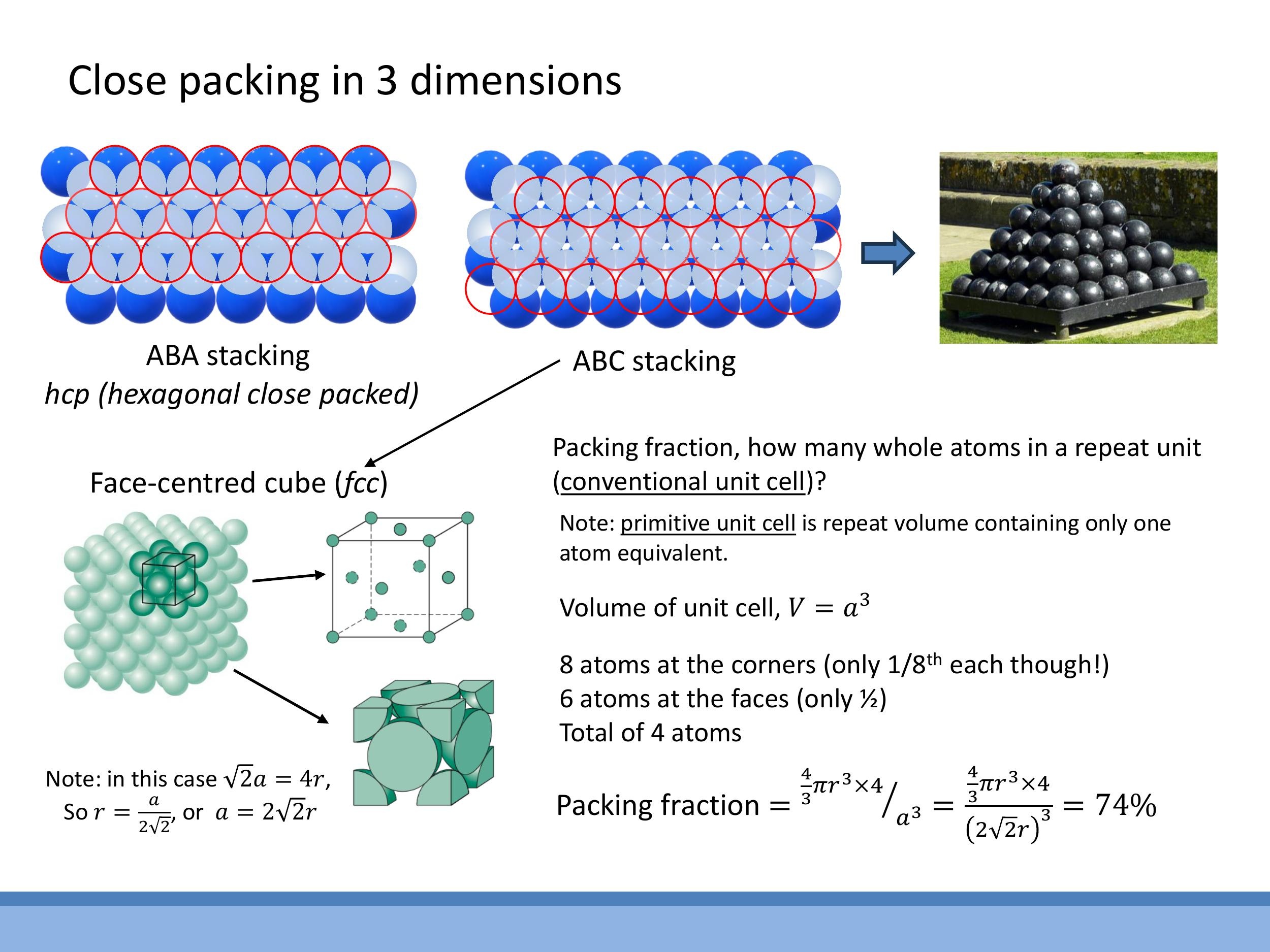

For a face-centred cubic (fcc) lattice, the relationship between the lattice parameter $a$ and the atomic radius $r$ is derived by considering atoms touching along the face diagonal. The length of the face diagonal is $\sqrt{2}a$. Since four atomic radii span this diagonal (one radius from each corner atom and two from the central face atom), we have $\sqrt{2}a = 4r$, which can be rearranged as $a = 2\sqrt{2}r$.

To calculate the packing fraction, the number of atoms per conventional fcc unit cell must first be determined. Each of the eight corner atoms contributes $\frac{1}{8}$ of an atom to the cell, totalling $8 \times \frac{1}{8} = 1$ atom. Each of the six face-centred atoms contributes $\frac{1}{2}$ of an atom to the cell, totalling $6 \times \frac{1}{2} = 3$ atoms. Therefore, a conventional fcc cell contains $1 + 3 = 4$ atoms.

The packing fraction is then calculated as the total volume occupied by these atoms divided by the total volume of the unit cell:

$$

\text{Packing Fraction} = \frac{4 \times \left(\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3\right)}{a^3}

$$

Substituting $a = 2\sqrt{2}r$:

$$

\text{Packing Fraction} = \frac{\frac{16}{3}\pi r^3}{(2\sqrt{2}r)^3} = \frac{\frac{16}{3}\pi r^3}{16\sqrt{2}r^3} = \frac{\pi}{3\sqrt{2}} \approx 0.74

$$

This result indicates a packing fraction of approximately $74 \% $. It is important to note that the hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure shares the same packing fraction, confirming that both fcc and hcp are considered close-packed structures.

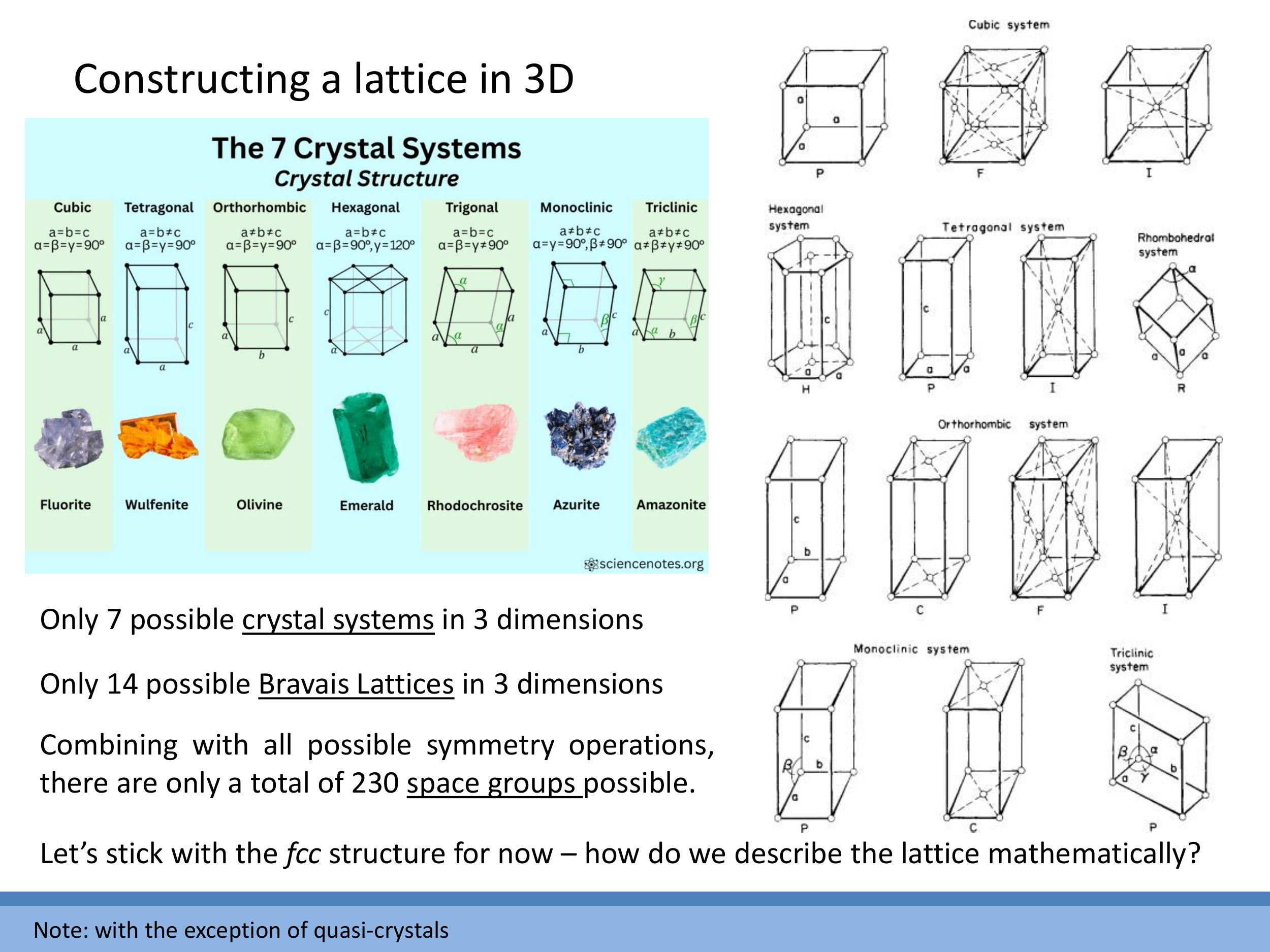

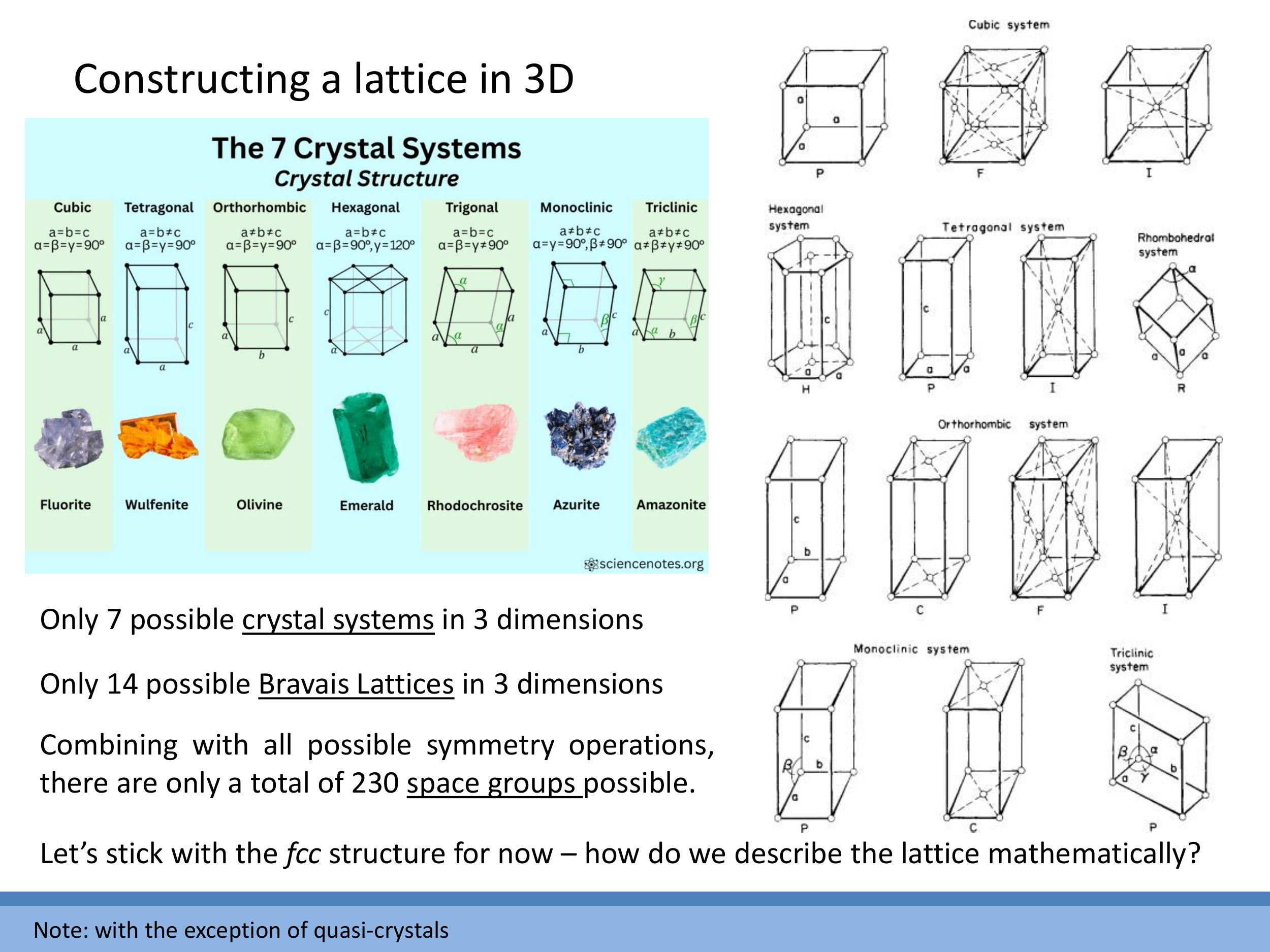

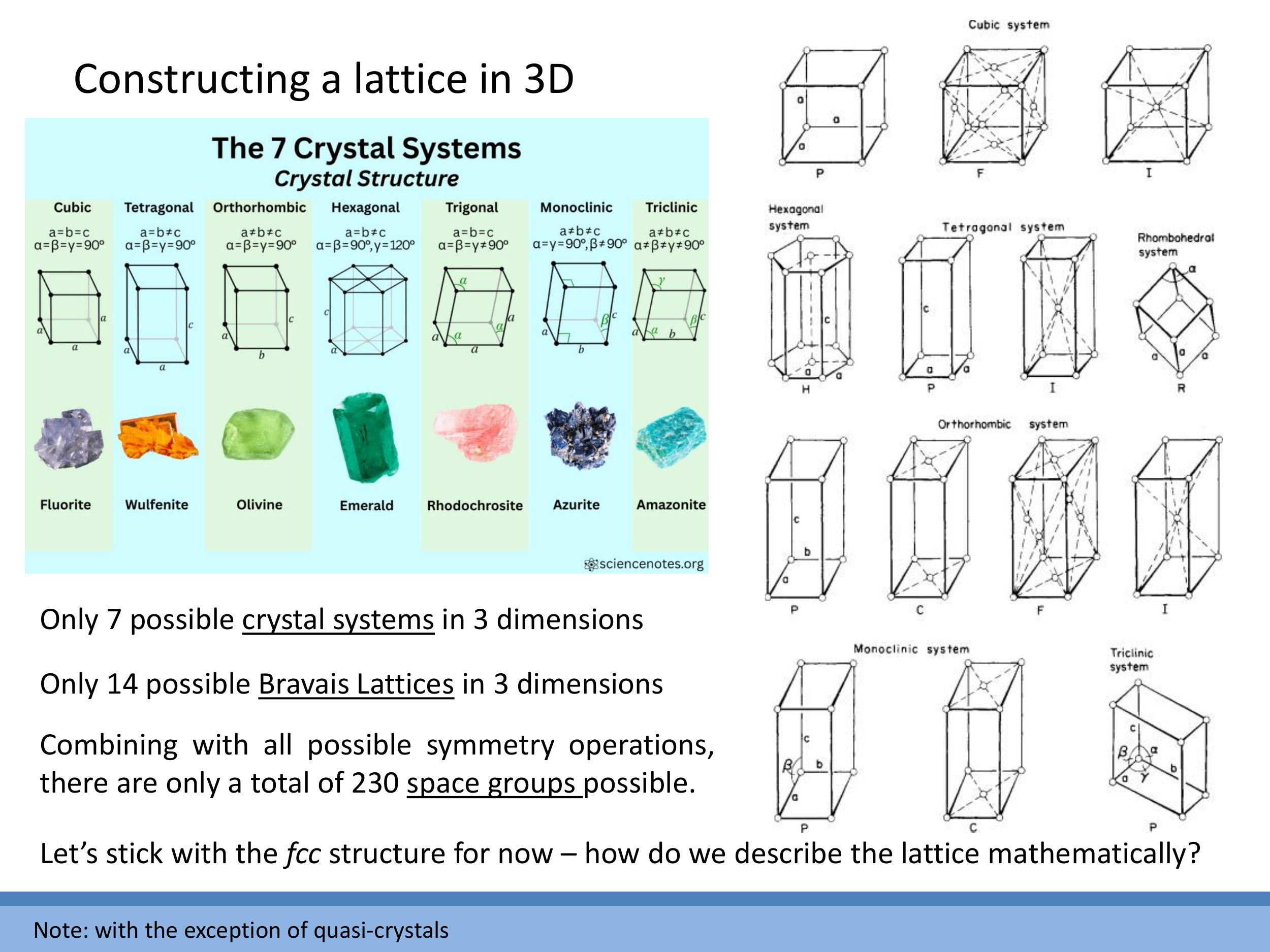

7) The classification landscape: 7 crystal systems and 14 Bravais lattices

Three-dimensional crystal structures are systematically classified based on their lattice parameters (edge lengths $a, b, c$) and interaxial angles ($\alpha, \beta, \gamma$). This classification yields seven distinct crystal systems: cubic, tetragonal, orthorhombic, hexagonal, trigonal, monoclinic, and triclinic. Each system defines a unique geometric pattern for the unit cell.

These seven crystal systems, when combined with all possible translational symmetries, give rise to a total of 14 Bravais lattices. These 14 lattices represent the only distinct ways to arrange points in three-dimensional space such that the environment around each point is identical.

Beyond Bravais lattices, combining these with various symmetry operations (such as rotation axes, mirror planes, and glide planes) results in a more detailed classification known as space groups. There are a total of 230 unique space groups, which provide a comprehensive description of all possible crystal symmetries.

8) Hands-on observation: macroscopic crystal shapes reflect symmetry

During the lecture, physical crystals such as iron pyrite (fool's gold, which exhibits cubic symmetry), selenite, and quartz were passed around for observation. Models of face-centred cubic (fcc) and body-centred cubic (bcc) structures were also shown. These demonstrations illustrated that slowly grown crystals often display external faces and overall macroscopic shapes that are consistent with their underlying internal atomic symmetry, providing a visual link between the microscopic and macroscopic properties of crystalline materials.

Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

Content pertaining to directions and planes (Miller indices), presented on slides PoM_lecture_14_page_10.jpg, PoM_lecture_14_page_11.jpg, PoM_lecture_14_page_12.jpg, and PoM_lecture_14_page_13.jpg, was introduced but explicitly deferred to the next lecture. Therefore, their content is not included here.

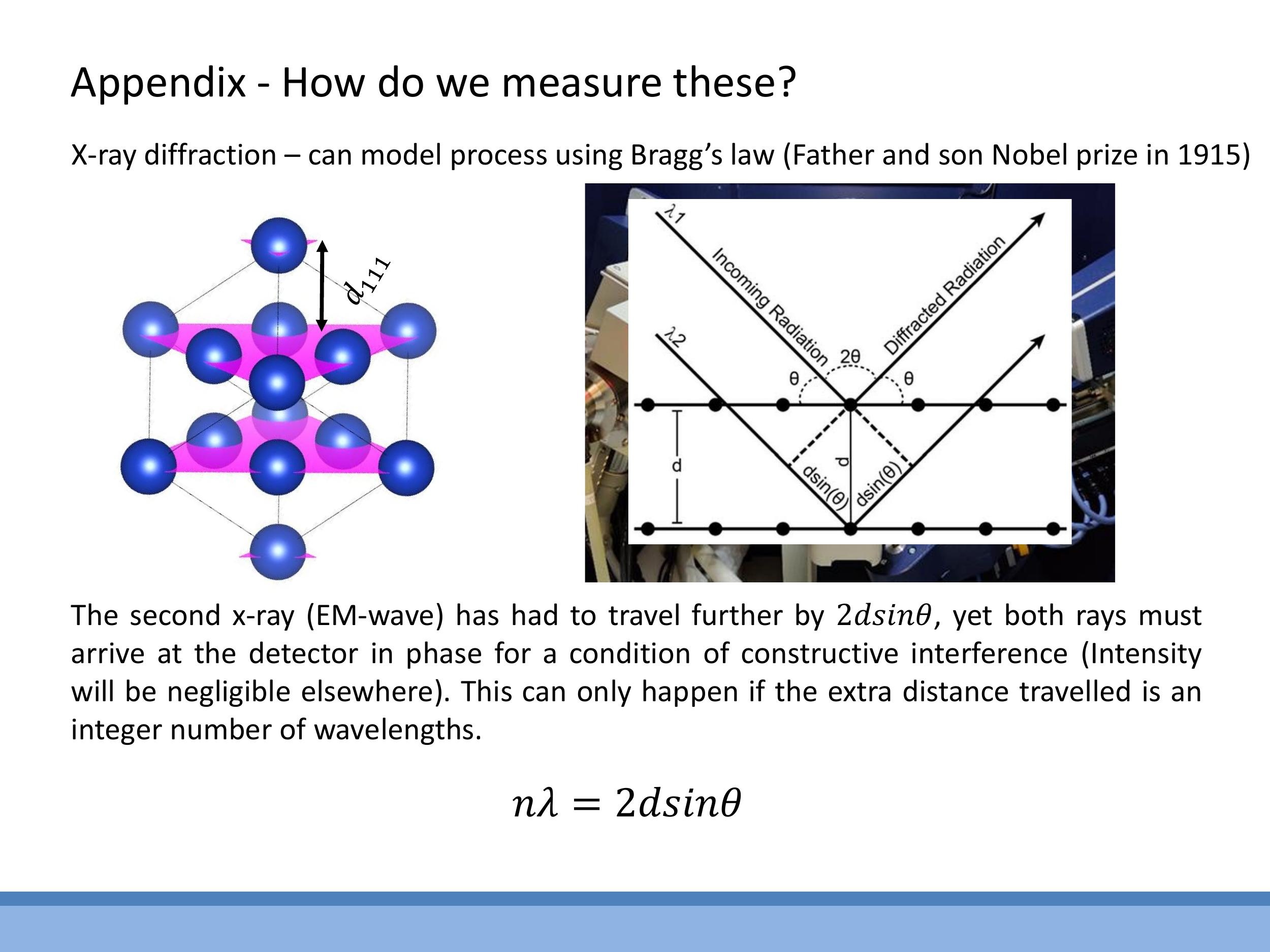

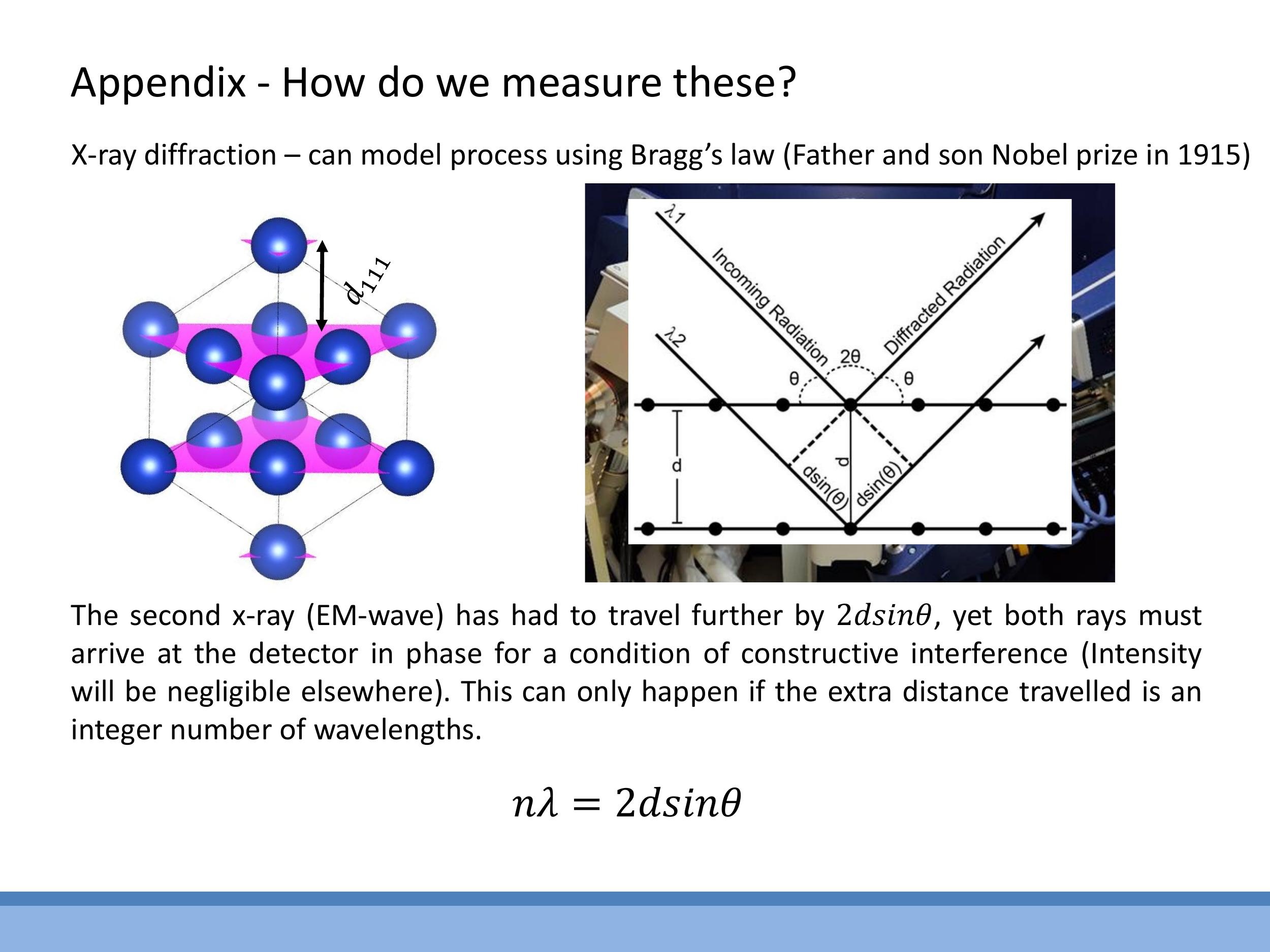

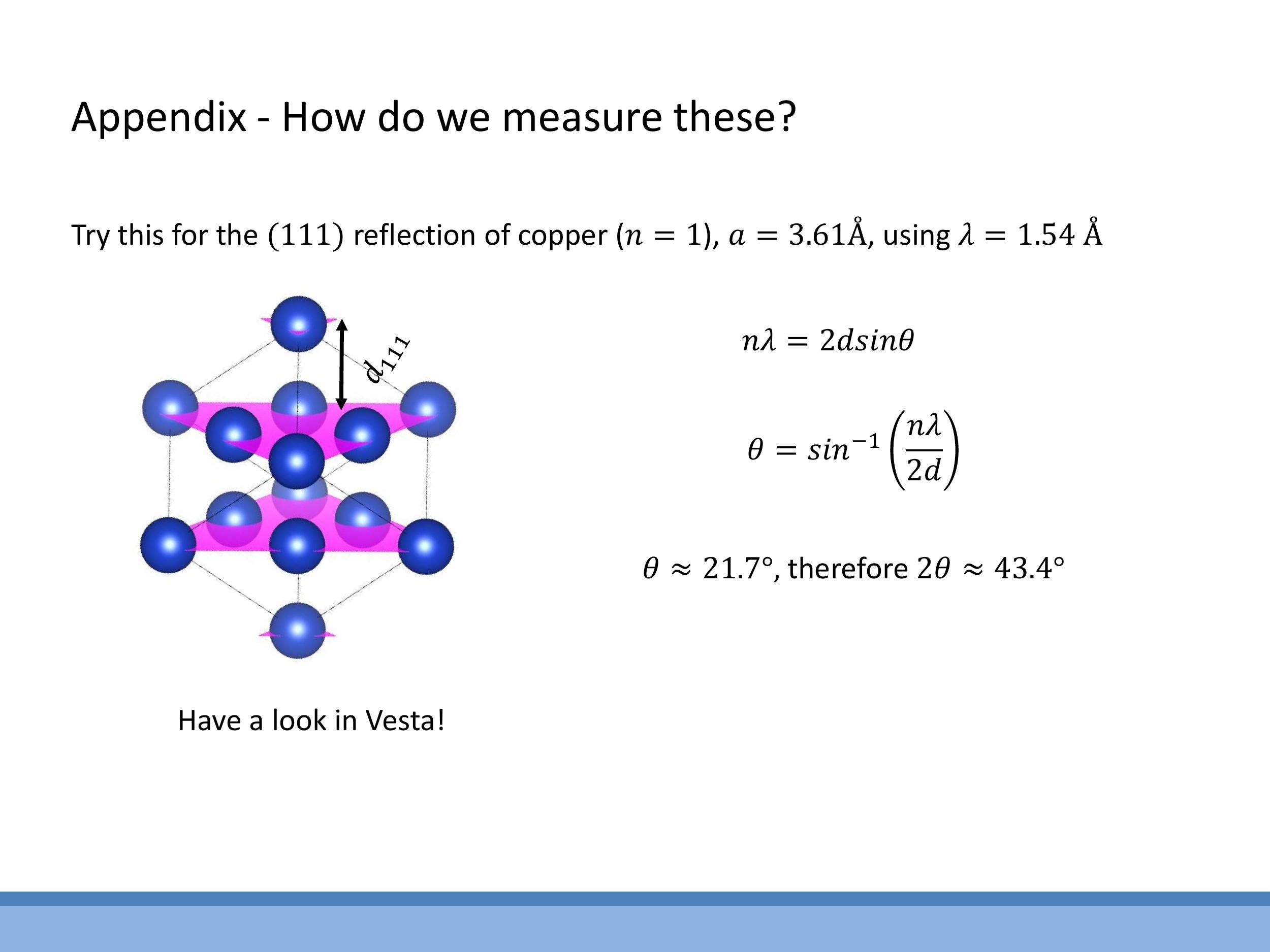

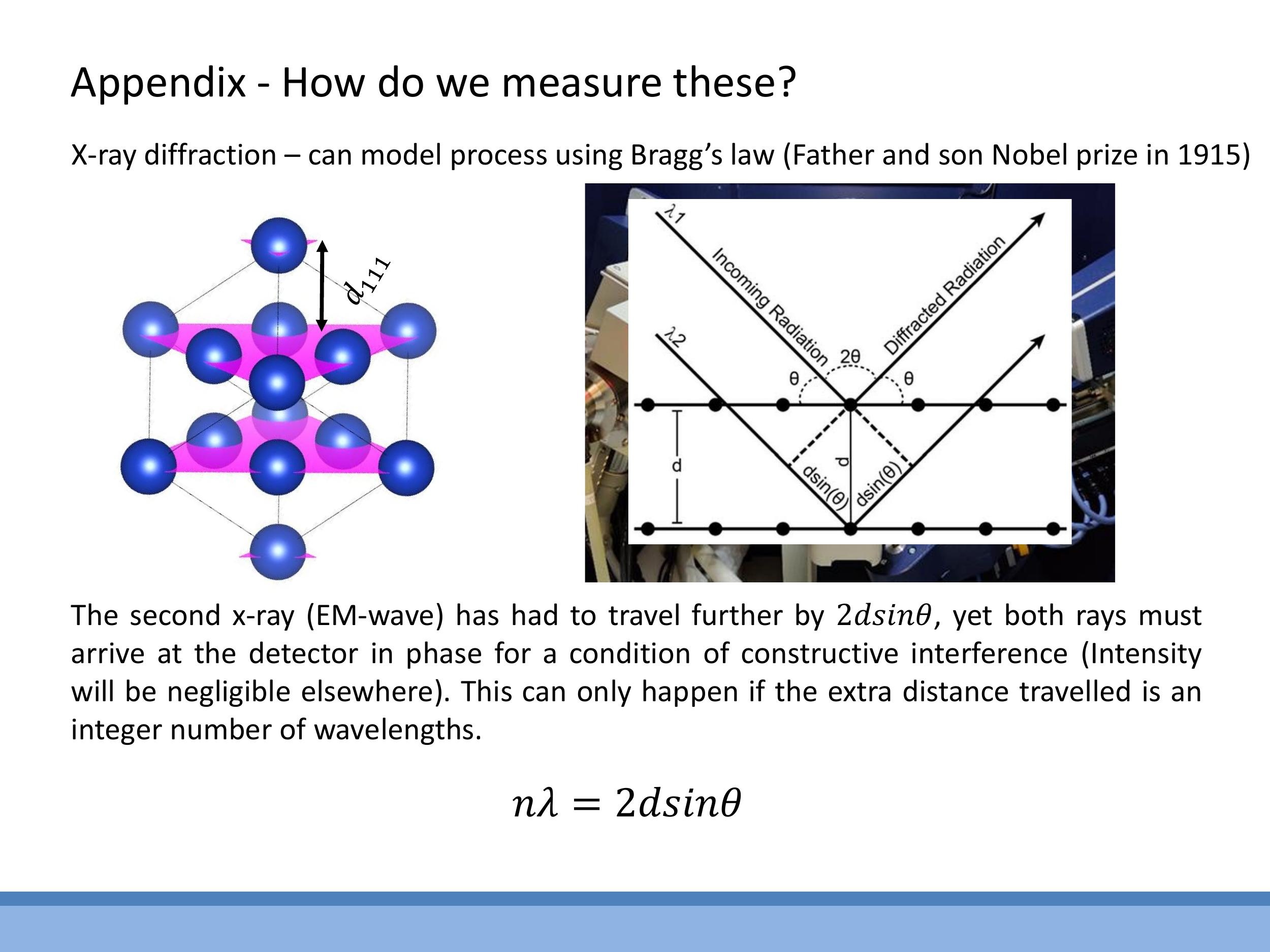

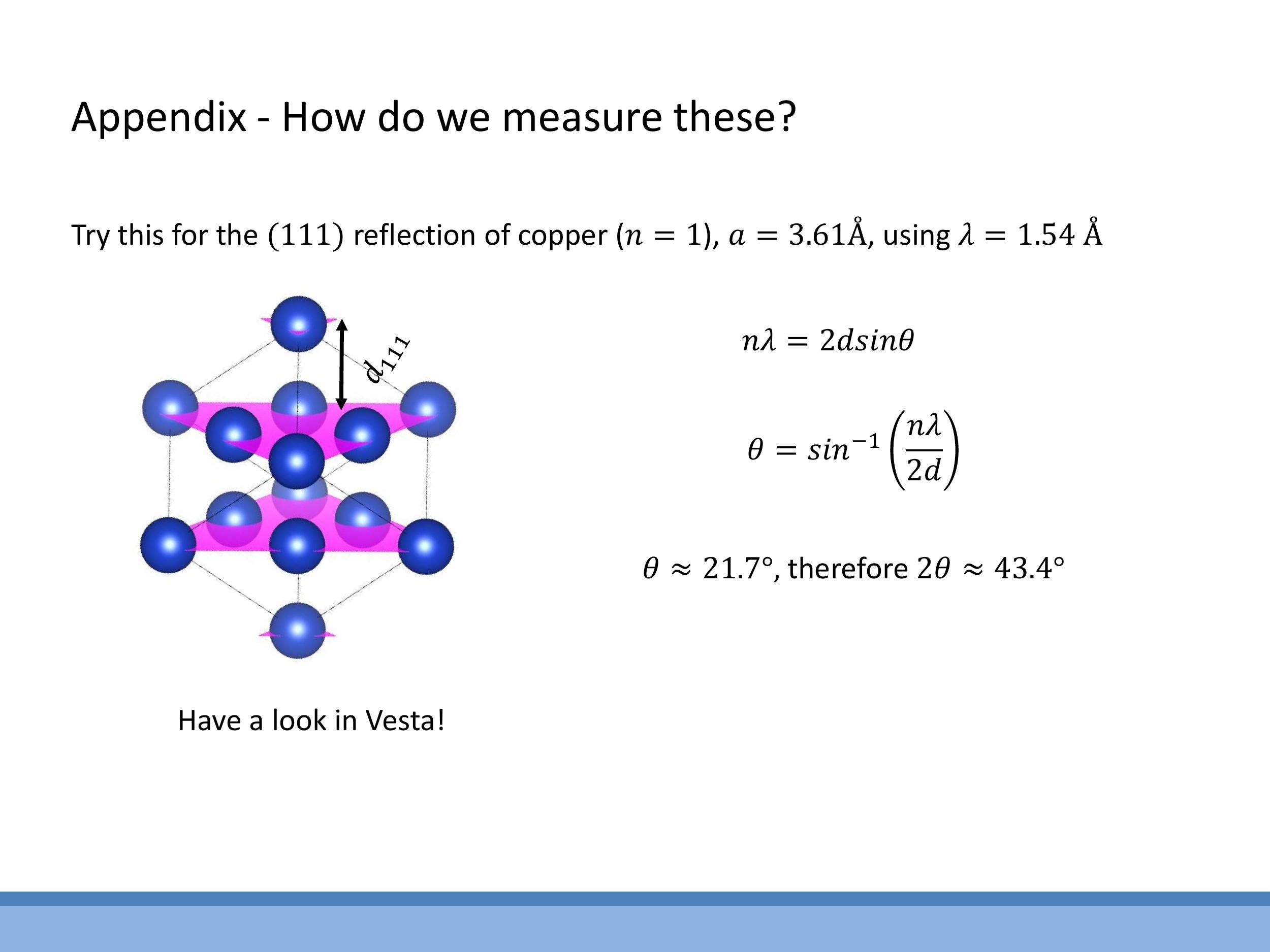

Appendix: Bragg’s law and measuring lattice spacings (supplementary)

Side Note: This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

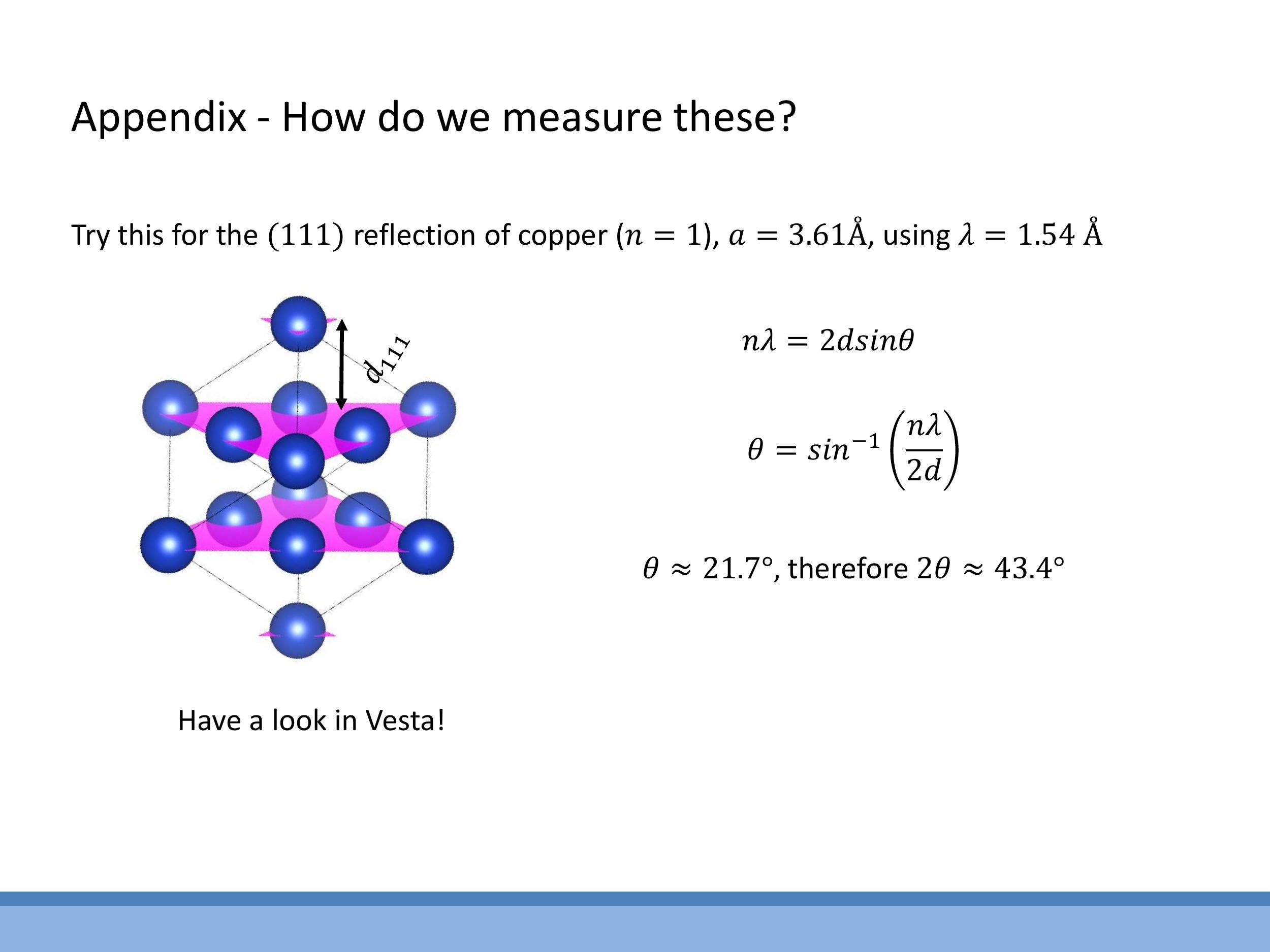

X-ray diffraction provides a method to access interplanar spacings, $d$, within a crystal lattice, governed by Bragg's law: $n\lambda = 2d \sin\theta$. This equation relates the wavelength of the X-rays, $\lambda$, the angle of incidence, $\theta$, and an integer $n$ representing the order of diffraction. Typically, this technique is used to identify which crystallographic planes $(hkl)$ diffract at specific angles $\theta$ for a given X-ray wavelength $\lambda$, thereby allowing the inference of $d$ and, consequently, the lattice parameters of the material. For instance, the copper (111) reflection with a characteristic X-ray wavelength of approximately $1.54 \, \text{Å} $ yields a specific $ 2\theta$ angle, directly linking to the fcc spacing relations discussed in this lecture.

Key takeaways

Solids are rigid and incompressible due to the balance of short-range attractive forces that fix atoms in place and steep short-range repulsive forces that resist compression. At the microscopic level, atoms in solids primarily exhibit vibrational motion about fixed positions, with insufficient kinetic energy for translational flow.

Crystalline solids are distinguished by their long-range periodic order, whereas amorphous solids, while maintaining fixed atomic positions, lack this extended periodicity. Most real-world crystalline materials are polycrystalline, composed of numerous single-crystal grains with varying orientations.

Modelling atoms as hard spheres provides insight into packing efficiencies. In two dimensions, square packing achieves approximately $78.5 \% $ efficiency, while hexagonal packing is denser at roughly $ 90.7 \% $. In three dimensions, stacking hexagonally packed layers leads to two close-packed structures: hexagonal close-packed (hcp) with an ABAB stacking sequence and face-centred cubic (fcc) with an ABCABC sequence; both achieve a maximum packing fraction of approximately $ 74 \% $.

The three cubic Bravais lattices are simple cubic (sc), body-centred cubic (bcc), and face-centred cubic (fcc). Their respective coordination numbers (number of nearest neighbours) are 6, 8, and 12. For fcc structures, the lattice parameter $a$ and atomic radius $r$ are related by $\sqrt{2}a = 4r$, and the packing fraction is approximately $74 \% $.

Beyond the cubic system, there are a total of seven crystal systems and fourteen Bravais lattices in three dimensions, representing all possible symmetric arrangements of points. When combined with various symmetry operations, these form 230 space groups.

Content on Miller indices was deferred to the next lecture. Bragg's law, presented in the appendix, is for contextual interest only and is not examinable this year.

## Lecture 14: Solids and Crystals

### 0) Orientation, admin, and learning outcomes

The problems class scheduled for Friday has been cancelled. It will be replaced by a two-hour revision session next week, covering both Mechanics and Properties of Matter. This session will be recorded. During the revision session, the lecturer will highlight slides that are typically relevant to exam-style questions, noting that the December test consists of ten multiple-choice questions, which constrains the format of questions.

This lecture marks a transition in the course, moving from the study of thermodynamics back to the discussion of material phases, with a specific focus on solids.

Upon completion of this lecture, students should be able to define and characterise a solid, define a crystal, and recall that there are seven crystal systems and fourteen Bravais lattices (memorisation of all is not required for first year). Students should also be able to draw and describe the three cubic Bravais lattices (simple cubic, body-centred cubic, and face-centred cubic), and calculate packing fractions for these structures.

### 1) What is a solid? Macroscopic properties and microscopic picture

Solids are characterised by two primary macroscopic properties: incompressibility and rigidity. Incompressibility arises from steep short-range repulsive forces between atoms, making it very difficult to force them closer together. Rigidity is a result of net attractive forces that hold atoms in fixed positions, resisting shear or flow.

From a microscopic perspective, the defining behaviour of atoms in a solid is that their kinetic energies are significantly less than their binding energies. This energy imbalance means that atoms in a solid do not exhibit translational motion, preventing any flow. Instead, their kinetic energy is confined solely to vibrations about fixed equilibrium positions. This contrasts with liquids, where atomic kinetic energies are comparable to bonding energies, allowing atoms to rearrange and flow past one another.

### 2) Crystalline vs amorphous; grains and real materials

Solids can be broadly classified into two structural types: crystalline and amorphous. Crystalline solids possess a periodic, repeating arrangement of atoms, where each atom experiences an identical local environment. In contrast, amorphous solids have atoms fixed in position but lack long-range periodicity, resulting in a more random structure; examples include polymers, wood, and glass.

Most everyday crystalline materials are polycrystalline, meaning they are composed of many small, single-crystal regions known as grains, each with a different crystallographic orientation. A common example is the glinting observed on steel railings in sunlight, which is caused by light reflecting off these differently oriented crystallographic grains.

The internal structure of materials can be visualised experimentally using electron microscopy techniques. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) can reveal grains and their orientations at the micron scale. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) offers a higher resolution, capable of showing atomic rows within a single grain, providing direct evidence of the material's atomic-scale periodicity.

### 3) Packing atoms as spheres in 2D: from square to hexagonal

To understand crystal structures, atoms are often approximated as identical hard spheres, and their packing efficiency is investigated. The lattice parameter $a$ is defined as the repeating distance between equivalent sites in the lattice.

For a square (simple) 2D lattice, the lattice parameter $a = 2r$, where $r$ is the atomic radius. The conventional unit cell is a square containing one atom (from four quarter-atoms at the corners). The packing fraction is calculated as the area of the atom(s) within the cell divided by the area of the cell: $\frac{\pi r^2}{(2r)^2} = \frac{\pi}{4} \approx 78.5\%$.

A denser arrangement is found in the hexagonal 2D lattice. The repeat unit for this structure is a parallelogram composed of two equilateral triangles, which still contains one atom equivalent. The packing fraction for this arrangement is $\frac{\pi r^2}{\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} (2r)^2\right)} = \frac{\pi}{2\sqrt{3}} \approx 90.7\%$, demonstrating a significantly more efficient packing.

Crystal lattices exhibit translational invariance, meaning any lattice point can be reached from another by integer steps along two basis vectors, $\vec{r} = u\vec{a} + v\vec{b}$, where $u$ and $v$ are integers. In two dimensions, there are only five possible Bravais lattices that exhibit this periodicity: oblique, square, rectangular, hexagonal, and rhombic (also known as centred rectangular).

### 4) From 2D layers to 3D close packing: hcp and fcc

Extending the packing concept to three dimensions begins with a hexagonally packed two-dimensional layer. Subsequent layers of spheres are placed into the gaps of the layer below. This leads to two primary close-packing sequences. The ABAB... stacking sequence, where every other layer aligns directly with the first, results in a hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure. Alternatively, the ABCABC... stacking sequence, where each new layer occupies a different set of gaps from the previous two, forms a face-centred cubic (fcc) structure. Both hcp and fcc arrangements achieve the same maximum packing fraction, representing the densest possible sphere packings in three dimensions. For the purposes of this course, calculations will primarily focus on cubic structures.

### 5) The three cubic Bravais lattices; coordination and unit cells

The cubic crystal system includes three distinct Bravais lattices, all defined by a conventional unit cell with an edge length $a$:

* **Simple Cubic (sc):** Atoms are located only at the corners of the cube. This arrangement is rare in nature due to its inefficient packing.

* **Body-Centred Cubic (bcc):** Atoms are found at each corner of the cube, with an additional atom situated at the exact centre of the cube (e.g., iron at certain temperatures).

* **Face-Centred Cubic (fcc):** Atoms are positioned at each corner of the cube and at the centre of each of the six faces (e.g., copper).

The coordination number quantifies the number of nearest neighbours surrounding a central atom in a given lattice. For simple cubic (sc) structures, the coordination number is 6. In body-centred cubic (bcc) structures, it is 8. For face-centred cubic (fcc) structures, the coordination number is 12. These numbers reflect how many nearest neighbours can geometrically fit around a central atom in each lattice type.

The conventional unit cell is the intuitively obvious cubic structure, containing atoms at corners and potentially face or body sites. In contrast, a primitive unit cell is the smallest volume that contains only one atom-equivalent. While primitive cells are fundamental, they are often less intuitive and are generally not used for describing cubic metals in this context, where the conventional cell is preferred for clarity.

### 6) Worked density result: fcc packing fraction ≈ 74%

For a face-centred cubic (fcc) lattice, the relationship between the lattice parameter $a$ and the atomic radius $r$ is derived by considering atoms touching along the face diagonal. The length of the face diagonal is $\sqrt{2}a$. Since four atomic radii span this diagonal (one radius from each corner atom and two from the central face atom), we have $\sqrt{2}a = 4r$, which can be rearranged as $a = 2\sqrt{2}r$.

To calculate the packing fraction, the number of atoms per conventional fcc unit cell must first be determined. Each of the eight corner atoms contributes $\frac{1}{8}$ of an atom to the cell, totalling $8 \times \frac{1}{8} = 1$ atom. Each of the six face-centred atoms contributes $\frac{1}{2}$ of an atom to the cell, totalling $6 \times \frac{1}{2} = 3$ atoms. Therefore, a conventional fcc cell contains $1 + 3 = 4$ atoms.

The packing fraction is then calculated as the total volume occupied by these atoms divided by the total volume of the unit cell:

$$ \text{Packing Fraction} = \frac{4 \times \left(\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3\right)}{a^3} $$

Substituting $a = 2\sqrt{2}r$:

$$ \text{Packing Fraction} = \frac{\frac{16}{3}\pi r^3}{(2\sqrt{2}r)^3} = \frac{\frac{16}{3}\pi r^3}{16\sqrt{2}r^3} = \frac{\pi}{3\sqrt{2}} \approx 0.74 $$

This result indicates a packing fraction of approximately $74\%$. It is important to note that the hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure shares the same packing fraction, confirming that both fcc and hcp are considered close-packed structures.

### 7) The classification landscape: 7 crystal systems and 14 Bravais lattices

Three-dimensional crystal structures are systematically classified based on their lattice parameters (edge lengths $a, b, c$) and interaxial angles ($\alpha, \beta, \gamma$). This classification yields seven distinct crystal systems: cubic, tetragonal, orthorhombic, hexagonal, trigonal, monoclinic, and triclinic. Each system defines a unique geometric pattern for the unit cell.

These seven crystal systems, when combined with all possible translational symmetries, give rise to a total of 14 Bravais lattices. These 14 lattices represent the only distinct ways to arrange points in three-dimensional space such that the environment around each point is identical.

Beyond Bravais lattices, combining these with various symmetry operations (such as rotation axes, mirror planes, and glide planes) results in a more detailed classification known as space groups. There are a total of 230 unique space groups, which provide a comprehensive description of all possible crystal symmetries.

### 8) Hands-on observation: macroscopic crystal shapes reflect symmetry

During the lecture, physical crystals such as iron pyrite (fool's gold, which exhibits cubic symmetry), selenite, and quartz were passed around for observation. Models of face-centred cubic (fcc) and body-centred cubic (bcc) structures were also shown. These demonstrations illustrated that slowly grown crystals often display external faces and overall macroscopic shapes that are consistent with their underlying internal atomic symmetry, providing a visual link between the microscopic and macroscopic properties of crystalline materials.

### Slides present but not covered this lecture (for clarity)

Content pertaining to directions and planes (Miller indices), presented on slides `PoM_lecture_14_page_10.jpg`, `PoM_lecture_14_page_11.jpg`, `PoM_lecture_14_page_12.jpg`, and `PoM_lecture_14_page_13.jpg`, was introduced but explicitly deferred to the next lecture. Therefore, their content is not included here.

## Appendix: Bragg’s law and measuring lattice spacings (supplementary)

*Side Note:* This material is supplementary and won't be examined, but provides useful context.

X-ray diffraction provides a method to access interplanar spacings, $d$, within a crystal lattice, governed by Bragg's law: $n\lambda = 2d \sin\theta$. This equation relates the wavelength of the X-rays, $\lambda$, the angle of incidence, $\theta$, and an integer $n$ representing the order of diffraction. Typically, this technique is used to identify which crystallographic planes $(hkl)$ diffract at specific angles $\theta$ for a given X-ray wavelength $\lambda$, thereby allowing the inference of $d$ and, consequently, the lattice parameters of the material. For instance, the copper (111) reflection with a characteristic X-ray wavelength of approximately $1.54\,\text{Å}$ yields a specific $2\theta$ angle, directly linking to the fcc spacing relations discussed in this lecture.

## Key takeaways

Solids are rigid and incompressible due to the balance of short-range attractive forces that fix atoms in place and steep short-range repulsive forces that resist compression. At the microscopic level, atoms in solids primarily exhibit vibrational motion about fixed positions, with insufficient kinetic energy for translational flow.

Crystalline solids are distinguished by their long-range periodic order, whereas amorphous solids, while maintaining fixed atomic positions, lack this extended periodicity. Most real-world crystalline materials are polycrystalline, composed of numerous single-crystal grains with varying orientations.

Modelling atoms as hard spheres provides insight into packing efficiencies. In two dimensions, square packing achieves approximately $78.5\%$ efficiency, while hexagonal packing is denser at roughly $90.7\%$. In three dimensions, stacking hexagonally packed layers leads to two close-packed structures: hexagonal close-packed (hcp) with an ABAB stacking sequence and face-centred cubic (fcc) with an ABCABC sequence; both achieve a maximum packing fraction of approximately $74\%$.

The three cubic Bravais lattices are simple cubic (sc), body-centred cubic (bcc), and face-centred cubic (fcc). Their respective coordination numbers (number of nearest neighbours) are 6, 8, and 12. For fcc structures, the lattice parameter $a$ and atomic radius $r$ are related by $\sqrt{2}a = 4r$, and the packing fraction is approximately $74\%$.

Beyond the cubic system, there are a total of seven crystal systems and fourteen Bravais lattices in three dimensions, representing all possible symmetric arrangements of points. When combined with various symmetry operations, these form 230 space groups.

Content on Miller indices was deferred to the next lecture. Bragg's law, presented in the appendix, is for contextual interest only and is not examinable this year.